This is the history and experience of Palestinians from a Palestinian view. This is, for many Westerners, the side of the story they have never heard. It is heartening to read the latest poll figures showing that most Americans do not agree that Israel should be building settlements in the West Bank and that the American government is out of step with its own people every time it reaffirms a “special relationship” with Israel. See John Mearsheimer’s article, American Public Opinion and the Special Relationship with Israel.

This is the history and experience of Palestinians from a Palestinian view. This is, for many Westerners, the side of the story they have never heard. It is heartening to read the latest poll figures showing that most Americans do not agree that Israel should be building settlements in the West Bank and that the American government is out of step with its own people every time it reaffirms a “special relationship” with Israel. See John Mearsheimer’s article, American Public Opinion and the Special Relationship with Israel.

This post is another in my series highlighting key points in Nur Masalha’s historical research into the evidence for the Zionist plans to expel Palestinian Arabs from their lands that has been at the heart of the respective Israeli governments’ policies towards the Palestinians up to today (Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948).

The previous two posts in this series are:

- Zionist Founding Fathers’ Plans for Transfer of the Palestinian Arabs

- Redemption or Conquest: Zionist Yishuv Plans for Transfer of Palestinian Arabs in British Mandate Period

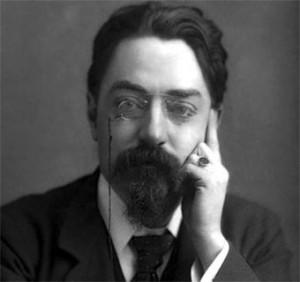

Chaim Weizemann, who was to become the first president of the state of Israel, but at this time was president of both the Zionist Organization and the newly established Jewish Agency Executive, actively began promoting the idea of ethnic cleansing (or more politically correctly, ‘Arab transfer’) in private meetings with British government officials and ministers against the background of the violence of the August 1929 violence between Jews and Arabs.

The Arab-Jewish clashes of August 1929

The British Government commissioned a report into the causes of the uprising and its findings are significant for what they indicate about the struggle between Zionist Jews and Palestinian Arabs ever since.

The uprising followed a political demonstration by militant Revisionist Jews at the Wailing Wall next to the Haram al-Shaif, Islam’s third holiest site.

133 Jews, including women and children, were killed.

Reasons for the violence

March 1930 the Shaw Commission (Cmd. 3530) submitted its findings:

Arabs have come to see in Jewish immigration not only a menace to their livelihood, but a possible overlord of the future.

“It further signalled the seriousness of landlessness among Palestinian peasants, and warned that further Zionist colonization would exacerbate an already grave problem.” Masalha, p.31

Why the landlessness of so many Palestinians?

Absentee landlords had sold the land to Zionist agencies tasked with buying up the land. (See previous post.)

Peasant tenancy had evolved into a permanent institution in Arab villages, and was not different from outright ownership except in the payment of ground rent by the tenants. Almost invariably, the tenants had cultivated the land for generations, and many had once owned the land they farmed but had been forced at some point to sell to creditors or absentee landlords. The fact that the tenant farmers, more or less oblivious to the legal status of the land, regarded the land as their own property only increased their bitterness when they were forced to vacate it. (p. 31)

The “statesmanship” of Weizmann’s secret ethnic transfer proposals

Weizmann’s secret meeting with the Shaw Commission

This information is based on Weizmann’s notes on the meeting held in a private room in the House of Commons, available in The Letters and Papers of Chaim Weizmann. (My own emphases in the quotations.)

Weizmann met with the Shaw Commission before they had finalized their report and, well aware of the importance of the land-ownership issue as a major contributory factor to the violence, argued that it was Britain’s fault! The British government had insisted on separating Transjordan from “the greater land of Israel” that the Zionists claimed for their race. Had they not done so, Weizmann argued, the uprooted Palestinians could have found new land in the Jordan.

Weizmann’s secret meeting with Dr Shiels

The British Parliamentary Under Secretary for the Colonies, Dr Drummond Shiels, met with Weizmann and other Zionist leaders just prior to the release of the Shaw Commission’s report. Shiels had previously supported the Zionists in their demand that democratic self-government should be denied the Palestinians. This would not have been in Zionist interests while the Jews were only a numerical minority in Palestine.

Shiels made it clear to Wiezmann that “a transfer of the Arab population was desirable.” Weizmann wrote of this meeting:

Some radical solution must be found, and [Dr. Shiels] didn’t see why one should not really make Palestine a national home for the Jews and tell it frankly to the Arabs, pointing out that in Transjordan and Mesopotamia they had vast territories where they could work without let or hindrance. . . Weizmann replied that a solution like that was a courageous and statesmanlike attempt to grapple with a problem that had been tackled hitherto half-heartedly; that if the Jews were allowed to develop their National Home in Palestine unhindered the Arabs would certainly not suffer — as they hadn’t hitherto. Some might flow off into neighbouring countries, and this quasi exchange of population could be fostered and encouraged. It had been done with signal success under the aegis of the League of Nations in the case of the Greeks and Turks.

Weizmann’s secret meeting with Lord Passfield

Lord Passfield (Sidney Webb, the colonial secretary), also just prior to the release of the Shaw report, met with Weizmann and said that from what he had heard of the soon-t0-be-released report,

the only grave question that it had revealed was the problem of [Arab] tenants on land which had been acquired by Zionist[s], [and that] the cumulative effect of this process, if it continued, might produce a landless proletariat, which would be a cause of unrest in the country.

Weizmann’s record of the conversation has Lord Passfield saying that re-settlement of the dispossessed Palestinians in the Transjordan “might be a way out” of the problem. This was Weizmann’s own view. He had blamed the British for the problem by removing Transjordan from the Mandate territory and preventing Jewish colonization there. Therefore, Weizmann wrote, “surely if we [the Jews] could not cross the Jordan the Arabs could. And this was applicable to Iraq.”

Again according to Weizmann’s record, Lord Passfield objected to Weizmann’s proposal that the evicted Palestinians should be sent to Iraq on the grounds that an independent government in Iraq might object to the idea. Weizmann responded:

My reply was: “Of course, it isn’t easy, but these countries have to be developed, and they cannot be developed capitalistically because of their political situation, but they could be colonised by Moslems, and possibly by Jews. One requires a great deal of preparation for it, and, in cooperation with the government we could attempt to negotiate with the Arabs” . . . . I then said, “supposing we were to create a Development Company which would acquire a million dunams of land in Transjordania, this would establish a reserve [for Arab resettlement] and relieve Palestine from pressure, if any should exist.

Telegram to Felix Green

Weizmann sent a telegram to Felix Green on 23 June asking for a detailed account of the land available in the Transjordan for the resettlement of proposed Palestinian transferees.

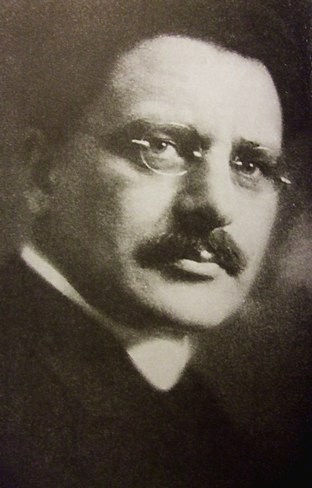

The Secret Weizmann-Rutenberg scheme for the transfer of the Palestinians

Thus for the first time the Zionist leadership of the Jewish settlers in Palestine presented the British government with an official, albeit secret, proposal for the expulsion of the Palestinians to the Transjordan.

Pinhas Rutenberg was an engineer, industrialist and financier and leading member of several Jewish Zionist and settlement organizations. He had earlier worked out a detailed plan for exploiting the waters of the Jordan and Yarmuk rivers for hydroelectricity for the Jewish settlements. Weizmann left the details of the plan to be worked out with him.

The result was the Weizmann-Rutenberg scheme of 1930.

This plan was presented to the British Colonial Office.

It asked for “a loan of one million Palestinian pounds to be raised from Jewish financial sources for the resettlement of Palestinian peasant communities in Transjordan, pending the granting of permission for Zionist settlement east of the Jordan River.”

The Colonial Office files remain classified. So we cannot know further details of the plan.

British rejection of the Zionist transfer plan

When the Shaw Commission’s report was released it had a significant impact on turning a hitherto predominantly pro-Zionist public to become more supportive of the Palestinian cause.

Lord Passfield himself had finally become sharply aware of the extent of Palestinian nationalist opposition to Zionism.

Lord Passfield (the Colonial Secretary) and the Prime Minister (Ramsey MacDonald) and the British treasury flatly rejected the Weizmann scheme for Palestinian transfer on the grounds of:

- prohibitive financial cost

- anticipated strength of Arab opposition

They made their objection clear in meetings with

- Weizmann himself, and

- Selig Brodetsky, president of the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland, and member of the Zionist Executive

They also ruled out any plan to allow the Jews to settle in the Transjordan.

Restrictions placed on Jewish immigration

Lord Passfield was responsible for a White Paper that further recommended

that restrictions be placed on Jewish immigration in order to alleviate the pressures on Palestinian peasants resulting from Zionist acquisition of the land they worked. (See Cmd 3692, Statement of Policy)

30% of rural Palestinians dispossessed

It had been officially estimated by this time that 29.4 percent of the rural population — 30,000 rural Palestinian families — had become landless. The subsequent Hope-Simpson report also made clear that “no additional land was available in Palestine for settlement by Jewish immigrants.”

Weizmann’s reaction to British rejection of the scheme

Weizmann used the Passfiled White Paper rejection of his plan to go public with his scheme. On 1 November 1930 in an article in the London-based Week End Review he wrote:

No statesmanlike view . . . could ignore the fact that Transjordan is legally part of Palestine . . . that in race, language and culture its people are indistinguishable from the Arabs of Western Palestine; that it is separated from Western Palestine only by a narrow stream; that is has been established as an Arab reserve, and that it would be just as easy for landless Arabs or cultivators from the congested areas to migrate to Transjordan as to migrate from one part of Western Palestine to another.

Weizmann continued in the meantime to attempt to persuade British officials to change their minds. He insisted that the problems with his scheme were solely financial, and that he could ensure a loan could be raised. But the loan would have to be guaranteed by the British, and the British would also have to agree to extending the Jewish settlement into the Transjordan as well.

Weizmann’s meeting with Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary

4 December 1930, Weizmann met with Ramsay MacDonald (PM) and Foreign Secretary Arthur Hendersen to propose a Round Table Conference with the Arabs to discuss the

problem of the congested area in Cisjordan [which] could be solved by development of, and migration of Arabs to, Tranjordania.

So we see here a continuation of developments described from their origins in my previous post(s). Zionist refusal to talk directly one-on-one with the Palestinians, and an assumption of the right of Jewish immigrants to permanently dispossess traditional Arab Palestinians and transfer them elsewhere. We also see an assumption of Zionist rights to claim the Transjordan.

As it turned out, the British rejection of Weizmann’s transfer proposal was only a temporary setback. But that will be discussed later.

All of Weizmann’s negotiations and meetings were very much kept behind closed doors. We know of them today from Government papers and Weizmann’s own diary and other correspondence.

Others who also proposed the transfer of the Palestinians

The Directorate of the Jewish National Fund (JNF) was the leading settlement organization. At a meeting on 17 June 1930 it proposed the transfer of Arabs from Palestine to Transjordan.

It repeated the proposal the next year at a meeting on 29 April 1931.

1931, the Jewish Agency submitted a proposal to a British appointed committee led by Lewis French to address the situation of dispossessed Arab farmers, in particular those of Wadi al-Hawarith evicted from lands sold to the Jewish National Fund by an absentee landlord.

The Agency proposed the removal of those dispossessed to Transjordan.

The British High Commissioner, Arthur Wauchope, rejected the Jewish Agency’s proposal “as an attempt to expel the country’s peasant population.”

1932, Victor Jacobson, representative of the Zionist Organization at the League of Nations and head of the Zionist political office in Paris, “suggested in a secret memorandum the partition of Palestine on condition that 120,000 Arabs be removed from the Jewish area.”

The need for discretion in public

Menahem Ussishkin, a leading figure of the Jewish settlers in Palestine (the Yishuv), and chairman of the Jewish National Fund and member of the Jewish Agency Executive, indiscreetly called for the transfer of the Arabs in an open public address to journalists in Jerusalem, 28 April 1930:

We must continually raise the demand that our land be returned to our possession . . . . if there are other inhabitants there, they must be transferred to some other place. We must take over the land. We have a greater and nobler ideal than preserving several hundred thousands of Arab fellahin.

Going public like this was an embarrassment to the Zionist cause. The Jewish Agency two days later passed a motion criticizing Ussishkin’s statement, “even though the Agency itself would propose a study involving transfer the following year, and Ussishkin’s own Jewish National Fund would submit a proposal recommending transfer to the Lewis French committee” (see above).

So the objection was not to the content of Ussishkin’s statements. It was to his going public with them. Going public with the transfer scheme only risked

- of Palestinian unrest

- intensifying pressure to halt Jewish immigration to Palestine

- of alienating public opinion in the West

The Weizmann’s transfer proposals laid the cornerstone of future policy arguments

Ongoing Zionist arguments to persuade the British to acquiesce to the transfer of the Palestinians were based on those of Weizmann’s 1930 scheme.

Jewish leaders in Palestine continued to insist there was nothing “immoral” about the idea of transferring Arabs they had dispossessed to other lands such as Transjordan or Iraq or any other part of the Arab world. The transfer of the Greek and Turkish populations was upheld as a precedent for the legitimacy of uprooting and transferring the Arab population out of Palestine.

(to be contd)

Related articles

- A century of deceit: World wars and Zionist militarism (alethonews.wordpress.com)

- 50 People in the Bible Confirmed Archaeologically (wakeupcallnews.blogspot.com)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

4 thoughts on “The Weizmann Plan to “Transfer” the Palestinians”