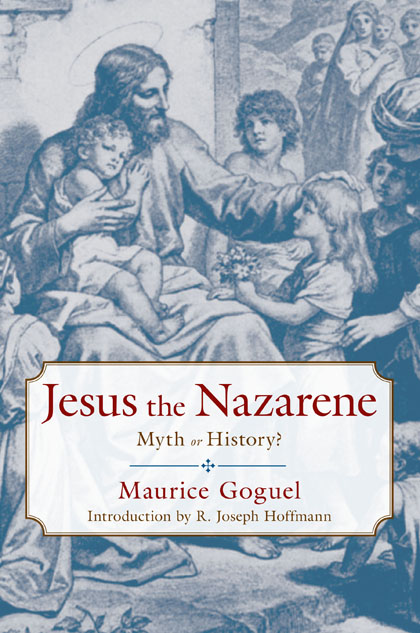

This post addresses R. Joseph Hoffmann’s discussion of Maurice Goguel’s 1926 defence of the historicity of Jesus in response to the early mythicist arguments, initially launched by Bruno Bauer in 1939, and developed in particular by Reinach, Drews and Couchoud. Hoffmann divides Goguel’s defence (Jesus the Nazarene: Myth or History?) into the following six sections. I have attempted to epitomize Hoffmann’s responses to each of the core arguments of Goguel for historicity. I have clearly indicated where I have departed from my understanding of Hoffmann’s own words and introduced my own comments.

This post addresses R. Joseph Hoffmann’s discussion of Maurice Goguel’s 1926 defence of the historicity of Jesus in response to the early mythicist arguments, initially launched by Bruno Bauer in 1939, and developed in particular by Reinach, Drews and Couchoud. Hoffmann divides Goguel’s defence (Jesus the Nazarene: Myth or History?) into the following six sections. I have attempted to epitomize Hoffmann’s responses to each of the core arguments of Goguel for historicity. I have clearly indicated where I have departed from my understanding of Hoffmann’s own words and introduced my own comments.

When I started this post I half expected it to become a response to historicist arguments in general, hence I sometimes speak of “some Jesus historicists” where Hoffmann is specifically addressing Goguel himself.

1. The notices of opponents

Goguel suggests that Christianity was recognized by outsiders at least from the time of Tacitus (55-120) and none of its opponents doubted the existence of Jesus.

Hoffmann responds:

Tacitus, even if his report (Annals 15.44) is authentic, is reporting on the teaching of the cult and not on historical records he is attempting to verify.

None of the pagan critics of Christianity cast doubt on the historicity of Jesus “for the simple reason that after the second century –the first age of Christian apologetics — the story was regarded as a canonical record of the life and teachings of an authentic individual, thus to be refuted on the basis of its content rather than the details of its historical veracity.”

The earliest official report referring to Christianity, the letter of governor Pliny to Emperor Trajan (111 ce), “knows nothing of a historical Jesus, only a cult that worships a certain Christ as a god (quasi deo).

Other critics such as Celsus, Porphyry and Julian found the idea of the historicity of Jesus a point in favour of their attacks on Christianity. They could mock the insignificance (not the nonexistence) of the Christian founder.

The inconspicuousness of Nazareth also lends credence to the myth theory. Was Jesus “the Nsr/Nazorean/Nazarene/Nazaraios” (my own variations of the word mixed with Hoffmann’s here) originally a divine name, as in Joshua the protector or saviour? Compare Zeus Xenios, Hermes Psychopompos, Helios Mithras, Yahweh Sabaoth. The evangelists appear to struggle with placing the name as a geographical locality in their gospels. Opponents were happy to associate Jesus with an insignificant town, but Hoffmann’s point is that the confusion over this epithet is embedded in the earliest debates over whether it was a local or a divine title.

2. The Docetic heresies

The various docetic views held that Jesus was not truly flesh, but a spirit, perhaps only appearing as a flesh and blood human. Some Jesus historicists have argued that when orthodox Christianity combatted these views, they were indeed affirming the historical reality of Jesus.

But this misses the point of what the debate was about. The issue was not whether Jesus had lived in the time of Pilate, but about the “materiality” of Jesus — was he manifest as real flesh and blood or only an apparition.

The existence of such docetic views among a range of Christian groups may well have been vestiges of some “pre-Christian” Jesus myth. But those arguing for the historicity of Jesus have focussed only on the orthodox response to docetic views, without really addressing the full complexity of its implications.

Is is not a myth the church was refuting in attacking Docetism; it was the belief that Jesus was of a different order of reality than the dichotomous reality it attributed to him as both god and man. Church fathers such as Irenaeus and Tertullian will accuse the Gnostics of believing in a phantasm, an apparition, a ghost, a spirit, in order to malign their opponents’ denial of the physical Jesus, but at no point do they accuse their enemies of creating a deception or myth. (pp. 26-27)

3. Paul and the Gospel

Opponents of the mythical Jesus idea have claimed mythicists make far too much of Paul’s silence on the details of the earthly career of Jesus. Continue reading “Weaknesses of traditional anti-mythicist arguments”

R. Joseph Hoffmann has in interesting introduction to his (re)publication of

R. Joseph Hoffmann has in interesting introduction to his (re)publication of

The following are the arguments for the historicity of Jesus. I have taken them from Dr James McGrath’s various comments to posts on this blog, and they are essentially direct quotations of his words. I want to be clear that none of my engagements with the methodology of historical Jesus scholars misrepresents any of the following arguments.

The following are the arguments for the historicity of Jesus. I have taken them from Dr James McGrath’s various comments to posts on this blog, and they are essentially direct quotations of his words. I want to be clear that none of my engagements with the methodology of historical Jesus scholars misrepresents any of the following arguments.

Niels Peter Lemche has a chapter in Lester Grabbe’s

Niels Peter Lemche has a chapter in Lester Grabbe’s