Before we begin, let’s be clear about what the word genocide means. The following is from the United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect

GenocideBackgroundThe word “genocide” was first coined by Polish lawyer Raphäel Lemkin in 1944 in his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. It consists of the Greek prefix genos, meaning race or tribe, and the Latin suffix cide, meaning killing. Lemkin developed the term partly in response to the Nazi policies of systematic murder of Jewish people during the Holocaust, but also in response to previous instances in history of targeted actions aimed at the destruction of particular groups of people. Later on, Raphäel Lemkin led the campaign to have genocide recognised and codified as an international crime. Genocide was first recognised as a crime under international law in 1946 by the United Nations General Assembly . . . . . DefinitionConvention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of GenocideArticle II In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

Elements of the crimeThe Genocide Convention establishes in Article I that the crime of genocide may take place in the context of an armed conflict, international or non-international, but also in the context of a peaceful situation. The latter is less common but still possible. The same article establishes the obligation of the contracting parties to prevent and to punish the crime of genocide. The popular understanding of what constitutes genocide tends to be broader than the content of the norm under international law. Article II of the Genocide Convention contains a narrow definition of the crime of genocide, which includes two main elements:

|

So the actual killing may have its limits. Genocide does not necessarily mean that every single person of a group has to be killed. There can come a time when the targeted group is so reduced that the group doing the killing starts to feel actual pity for the remaining few.

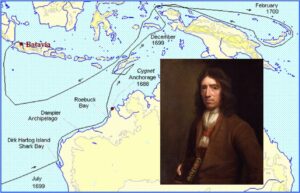

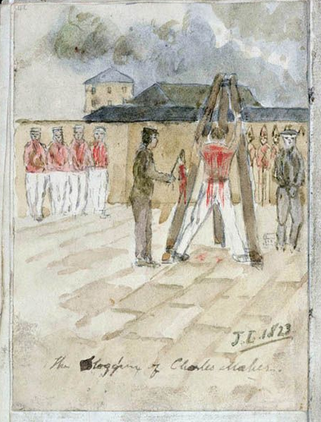

Case in point: Australia, 1860s.

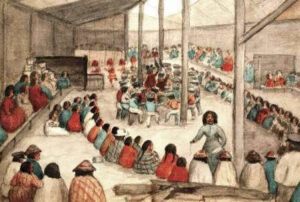

Uhr and his men set up camp at Pelican Lake in Valley of Lagoons in about September 1865. In theory, he was responsible for a vast territory stretching from the Pacific to the Gulf of Carpentaria and miles north towards Cape York. But his essential task was to police the country seized by Herbert, Dalrymple and the Scotts. That meant tangling with the Gugu Badhun, whose country covered about 3500 square miles running west from the Seaview Range. In Valley of Lagoons, they hunted kangaroo, trapped fish and harvested water-lily seeds in streams that never ran dry. It is thought that over a thousand Gugu Badhun were on country when the invaders came. The Scotts derided them:

I am sure they have not as keen senses as humans higher in the scale of humanity. “Like beasts, with lower pleasures; like beasts, with lower pains”. They have not the slightest sense of gratitude, in any kind of way; far less than a dog, or horse. Of course they know where they are well-treated, and well-fed. I believe fish, even, learn that.

The Scotts set about getting rid of them. In Gugu Badhun: People ofthe Valley ofLagoons, it is written: “After the establishment of the pastoral stations, any Gugu Badhun person who ventured into those areas risked being shot and killed.” But their resistance was strong. The country favoured them. “Their lands… included a good deal of rough, basalt country unsuitable for grazing sheep or cattle, but still holding water and food resources.” In that broken landscape, horses could not give chase to the Gugu Badhun who could hide in caves, biding their time until they emerged to attack again.

Arthur Scott, back in England to become a fellow of All Souls, was deeply worried about the run. At that point they had ninety white men on the payroll. He thought perhaps it was time to stop driving the blacks away and start putting them to work. He remarked that the Gugu Bad hun had already been given a “dressing” and believed that was enough to keep them in line.

I am rather sorry about those blacks; I think the time has now come to try & be friendly with them, we are strong enough now to defend ourselves & they would do a lot of work in washing… Certainly the best way will be to bring in some gins and boys & we shall soon make the others understand what we want. I am convinced that with our scrub & lava it is far more dangerous to keep them out than to let them in.

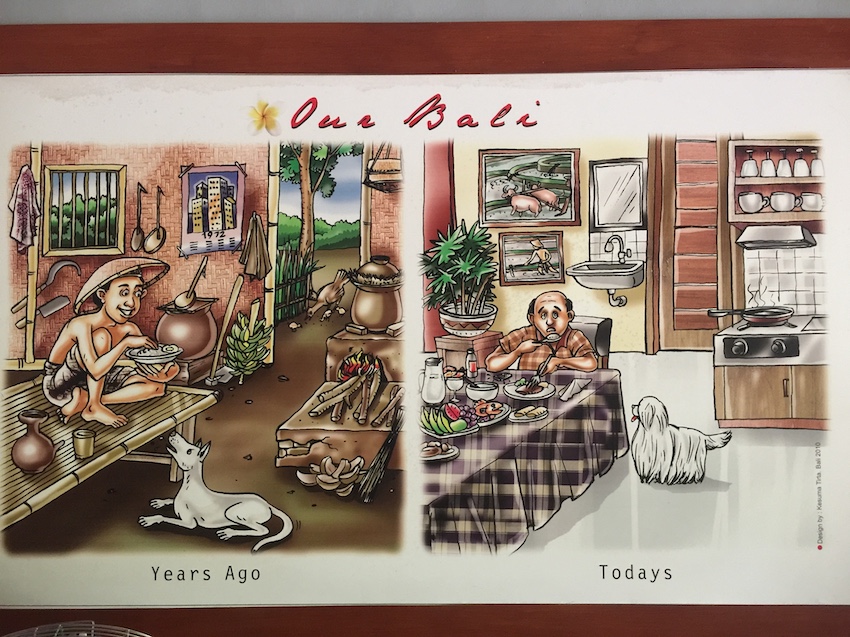

And so it was. Not quite as simply as might be implied by the above extract. Those habituated to killing needed more time to be persuaded. But the voices that had long been protesting the killing of the blacks throughout the early and middle decades of the nineteenth century did win out — but only after there were so few left that further killing seemed pointless; better to use the remaining few to do the menial work on the outback properties. Much cheaper than white labour, too, of course. When orphaned black children, helpless elderly, and struggling mothers dominated the remaining few, it was easy to have feelings of pity for them. So humanity “triumphed” and further killing was steadily, albeit slowly, forbidden in reality, not only in empty words of protest.

Quote, and the specific notion that the genocide of Australian aborigines only stopped, at least in the state of Queensland, when numbers of blacks were so few that enough whites began to feel sorry for them, is from:

- Marr, David. Killing for Country: A Family Story. Black Inc, 2023. pp 287f

P.S.

It was coincidence that I happened to be reading Killing for Country at the time when Israel began its bombing of Gaza. The idea for this post, however, was initiated through reflection on current events in the State of Palestine.