There is much in Costica Bradatan’s In Praise of Failure that I would like over time to address but let’s begin with the portion of Prologue that I quoted yesterday:

. . . . human existence is something that happens, briefly, between two instantiations of nothingness. Nothing first—dense, impenetrable nothingness. Then a flickering. Then nothing again, endlessly. “A brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness,” as Vladimir Nabokov would have it. . . .

That remark followed from his description of the feeling that we imagine would follow from surviving what at the time felt like plummeting to a certain death. I was reminded of that feeling from a real-life experience when I listened to the news last night about the death of the commander of 108 men who had fought off an attack of a 2500 strong enemy in the battle of Long Tan in 1966. He was quoted as having said that it was only a short time after the three hour battle that the full realization that he was “still alive” fell upon him.

I turned to the source of Bradatan’s quote. Here it is in (disturbingly colourful) context:

The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour). I know, however, of a young chronophobiac who experienced something like panic when looking for the first time at homemade movies that had been taken a few weeks before his birth. He saw a world that was practically unchanged— the same house, the same people—and then realized that he did not exist there at all and that nobody mourned his absence. He caught a glimpse of his mother waving from an upstairs window, and that unfamiliar gesture disturbed him, as if it were some mysterious farewell. But what particularly frightened him was the sight of a brand-new baby carriage standing there on the porch, with the smug, encroaching air of a coffin; even that was empty, as if, in the reverse course of events, his very bones had disintegrated.

As I quoted yesterday, Bradatan sees our “myths, religion, spirituality, philosophy, science, works of art and literature” as products of our efforts to make an “unbearable fact a little more bearable.” Continuing that thought, he writes,

One way to get around this is to deny the predicament altogether. It’s the optimistic, closed-eye way. Our condition, this line goes, is not that precarious after all. In some mythical narratives, we live elsewhere before we are born here, and we will reincarnate again after we die. Some religions go one step further and promise us life eternal. It’s good business, apparently, as takers have never been in short supply. More recently, something called transhumanism has entered this crowded market. The priests of the new cult swear that, with the right gadgets and technical adjustments (and the right bank accounts), human life will be prolonged indefinitely. Other immortality projects are likely to do just as well, for our mortality problem is unlikely to be resolved.

But this approach is not for everyone…

No matter how many of us buy into religion’s promise of life eternal, however, there will always be some who remain unpersuaded. As for the transhumanists, they may know the future, but they seem largely ignorant of the past: “human enhancement” products have, under different labels, been on the market at least since the passing of Enkidu of Gilgamesh fame. Compared with what the medieval alchemists had to offer, the transhumanists’ wares seem rather bland. Yet thousands of years of life prolongation efforts haven’t put death out of business. We may live longer lives today, but we still die eventually.

The Bullfighting way?

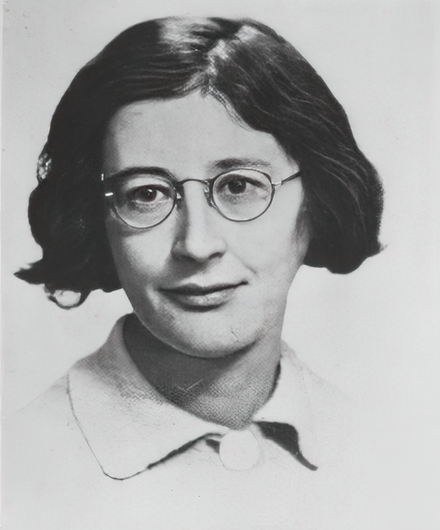

Bradatan finds himself siding with the views of Simone Weil:

Another way to deal with our next-to-nothingness is to confront it head-on, the bullfighting way: no escape routes, no safety nets, no sugarcoating. You just plow ahead, eyes wide open, always aware of what’s there: nothing. Remember the naked facts of our condition: nothing ahead and nothing behind. If you happen to obsess over your next-to-nothingness and cannot buy into the life eternal promised by religion or afford a biotechnologically prolonged life, this may be “right for you. Certainly, the bullfighting way is neither easy nor gentle—particularly for the bull. For that’s what we are, after all: the bull, waiting to be done in, not the bullfighter, who does the crushing and then goes on his way.

Hardly a higher form of human knowledge . . .

* Quoted in David McLellan, Utopian Pessimist: The Life and Thought of Simone Weil (New York: Poseidon Press, 1990), 93.Human beings are so made,” writes Simone Weil, that “the ones who do the crushing feel nothing; it is the person crushed who feels what is happening.”* Pessimistic as this may sound, there is hardly a higher form of human knowledge than the one that allows us to understand what is happening—to see things as they are, as opposed to how we would like them to be. Besides, an uncompromising pessimism is superbly feasible. Given the first commandment of the pessimist (“Whenever in doubt, assume the worst!”), you will never be taken by surprise. Whatever happens on the way, however bad, will not put you off balance. For this reason, those who approach their next-to-nothingness with open eyes manage to live lives of composure and equanimity, and rarely complain. The worst thing that could befall them is exactly what they have expected.

Above all, the eyes-wide-open approach allows us to extricate ourselves, with some dignity, from the entanglement that is human existence. Life is a chronic, addictive sickness, and we are in bad need of a cure.

The bolding is my own. I think that is worth taking in …. “there is hardly a higher form of human knowledge than the one that allows us to understand what is happening – to see things as they are”.

Somewhere in there we can find the real gift that can come from failure, or from the humility that it brings.

Bradatan, Costica. In Praise of Failure: Four Lessons in Humility. Cambridge, Massachusetts: *Harvard University Press, 2023.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

” . . . human existence is something that happens, briefly, between two instantiations of nothingness. Nothing first—dense, impenetrable nothingness. Then a flickering. Then nothing again, endlessly.”

“Flickering” may be overstating its duration. I’m not sure we’re alive for more than a moment at a time. I’m with the Buddhists: even the self is an illusion.

The self represents the physical fact that two units of life cannot occupy the same space and time. The self posits consciousness within itself, but consciousness resides also in all other units of life.

Yeah, and if we back away from the Earth, maybe to another galaxy, we are clearly too small to exist.

If taking a viewpoint many times the length of a human life makes it seem as if we are alive for just a trice, how about we move in to a time, only a tiny fraction of a second of time. At that scale we will live almost forever. (Mayflies think we are immortal, don’t you know.)

Are these people deliberately trying to devalue the time we are each allotted?

Yes and no. Acknowledging just how short (insignificant) our time is in the grand scheme of things makes it all the more precious (valued) to each of us.