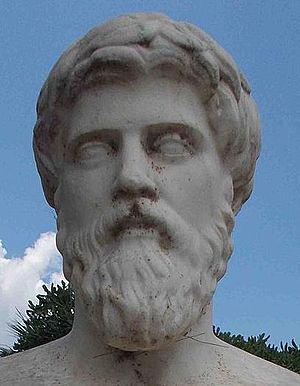

Because so many NT scholars desperately want the gospels to be both Greco-Roman biographies and reliable histories, we could almost forget that these two forms of literature are not the same. You don’t have to take my word for it. Here’s what Plutarch said:

It being my purpose to write the lives of Alexander the king, and of Caesar, by whom Pompey was destroyed, the multitude of their great actions affords so large a field that I were to blame if I should not by way of apology forewarn my reader that I have chosen rather to epitomize the most celebrated parts of their story, than to insist at large on every particular circumstance of it. It must be borne in mind that my design is not to write histories, but lives.

And the most glorious exploits do not always furnish us with the clearest discoveries of virtue or vice in men; sometimes a matter of less moment, an expression or a jest, informs us better of their characters and inclinations, than the most famous sieges, the greatest armaments, or the bloodiest battles whatsoever.

Therefore as portrait-painters are more exact in the lines and features of the face, in which the character is seen, than in the other parts of the body, so I must be allowed to give my more particular attention to the marks and indications of the souls of men, and while I endeavour by these to portray their lives, may be free to leave more weighty matters and great battles to be treated of by others. (Plutarch’s Alexander [emphasis and reformatting mine])

We could boil these comments down into the following points. A biography:

- Is not a history, and Plutarch wants his audience to know that.

- Is not necessarily exhaustive. It may not (and probably won’t) tell every story in a person’s life.

- Focuses on the person, not events.

- Recounts those events and (possibly off-handed) remarks that reveal the subject’s true character.

So according to Plutarch, a biography is not the history of a person, but rather “a word portrait” of a life. If he had meticulously recorded every event in the subject’s life, but neglected to tell us what motivated that person, he would consider it a failure. You can’t know a person without knowing what’s going on in his or her mind. In modern terms, we’d call this psychological motivation.

You may recall that the reason the so-called first quest of the historical Jesus collapsed was that German scholars concluded we could not write a life of Jesus. Even Mark, which, according to the developing consensus in the late 19th and early 20th centuries came first, arose out of the community of believers, and was completely colored by the theological concerns of that community.

Moreover, the gospels are devoid of motivation. We don’t know, for example, why Jesus in Luke 9:51 “set his face to go to Jerusalem,” other than it was time for him to do so. We don’t know why he showed compassion at one point, or anger the next. The evangelists can’t agree as to whether Jesus struggled over the imminent crucifixion (the Synoptics), or whether he was completely in accord with it (John). In either case, we don’t know why.

Given these facts, it’s impossible to imagine that Plutarch would consider the gospels biographies, even in the most general sense of the word. And if he wouldn’t, why should we?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Thanks for the information but still I am left confused on the nexus between them.

What I read in https://abcbiography.com is different from what is here.

Your link points to discussions about biographies written in modern times. For example, if anyone tried to write a biography of Flavius Josephus today, he or she would most certainly include a history of the region and the roots of the war before even starting on his life. I would probably spend a good bit of time explaining his patron and his relationship with Josephus.

But in ancient times — i.e., when Greco-Roman biographies were written — the typical method was to give a sketch of the subject’s life, with important events or sayings that represented the person’s salient traits.

In other words, today’s biographies are much more “histories of lives” than simply “stories about people.”