The best way to understand just how ‘non-religious’ or ‘non-biblical’ are the books of the New Testament — that is, to understand just how much a product of their own wider Greco-Roman literary culture are those books — is to read the popular novels of that era.

I enjoy both literature and ancient history so I loved reading the Collected Ancient Greek Novels edited by B. P. Reardon. They are called novels here, but they are otherwise labelled ‘novellas’, ‘erotic novels’ (from their theme of love at the behest of the god Eros), or ‘romances’.

So I was pleased to find that New Testament scholars have indeed been studying these and publishing on what they can teach us about the New Testament. (This was some years ago, but I am trying to catch up on years of reading on this blog.) One of these academics is Ronald F. Hock (I referred to him in my previous post) and it is my take on his chapter, “Why New Testament Scholars Should Read Ancient Novels” appearing in Ancient Fiction and Early Christian Narrative that I share in this post.

The novels most cited here are

Chaereas and Callirhoe by Chariton

Leucippe and Clitophon by Achilles Tatius

On the value of these novels for New Testament studies, Hock writes the following — and I have rearranged his paragraph-mass into an easy to skim column format:

they . . . provide the reader with a remarkably detailed, comprehensive, and coherent account of the social, economic, and religious institutions of the people and regions that witnessed the spread of Christianity into the Greek East of the early Roman Empire. (123)

The romances are set in Antioch, Tyre, Tarsus, Ephesus, Miletus, Alexandria, Paphos, Xanthus, and Tarentum, to name just a few of the cities mentioned in the New Testament, and in these cities we observe first-hand all sorts of people in ordinary and extraordinary situations — from the activities of the leading aristocratic families in the πόλις to those of the most marginalized shepherds and brigands in the χώρα and ἤρεμος. (124)

We see householders

- hosting symposia

- offering sacrifice

- visiting rural properties

- speaking in the theatre

- taking on public duties

- arranging marriages

- and making wills;

we see their wives

- attending religious festivals

- praying in temples

- punishing slaves

- and fleeing the ravages of war;

we see their sons

- attending the gymnasium

- hunting in the countryside

- participating in religious processions

- and visiting a hetaira;

their daughters

- playing the lyre

- walking in the garden adjacent to the house

- making seductive overtures to newly purchased slaves

- and participating in religious festivals.

We see domestic slaves

- managing households

- guarding doors

- pouring wine

- delivering letters

- exposing babies

- purchasing slaves

- grooming horses

- letting in adulterers

- receiving their freedom

- or suffering abuse

- and excruciating corporal punishment.

In addition, we see parasites enjoying the daily and extravagant board of their hosts

friends and freedmen accompanying the householder on trips

relatives being welcomed for visits

and even shipwrecked victims taken in and later provided with money and supplies for their return trip home.

Finally, we see the slaves and tenants on the aristocrats’ rural properties

- herding sheep and goats,

- digging pits to capture wolves

- picking grapes and making new wine

- fighting off the attacks of brigands

- counting the grains of wheat after a harvest

- playing the pan-pipes under a tree

- or swimming in the rivers

- catching birds with bird-lime

- greeting the Nymphs each morning

- and turning brigand when occasion arises.

For many of these activities the romances are sufficiently detailed to provide vivid descriptions of the conventions of thought and behavior that governed these activities.

Similar summaries are possible for any number of specific social institutions — for example,

- slavery

- brigandage

- travel

- burials

- symposia

- trials

- public and private festivals

- hunting

- and harvests.

And many intellectual activities receive their due as well —

- from learning letters

- to becoming familiar with literature,

- from mastering the skills needed to compose simple fables

- to the expertise required to compose and deliver complex prosecution and defense speeches.

In short, the romances are virtually an unparalleled, if underused, source for a wide range of social and intellectual institutions that characterized life in the Greco-Roman world during the New Testament period. (p. 125)

How the Romances Illuminate the New Testament

And yet, for New Testament scholars the real reason for reading the romances . . . . is their ability to clarify and illumine early Christian (and Jewish) literature. . . . (126)

Romancing the New Testament

First, then, a sampling of parallels — linguistic, grammatical, literary, and behavioral:

- A grammatical construction occurring often in the gospels is sometimes identified as an example of “Biblical Greek, originating in the LXX”, but the same expression is also found in the popular novels:

- the word for “some”, τινὲς, is omitted when used with “of” or “from” (ἀπὸ or ἐκ), in Matthew 23:24 — “some of them you will kill . . . some of them you will flog . . . “, where “some of” is rendered by the preposition “of”, ἐξ, alone; similarly in Mark 12:2 and John 7:40.

- Compare Longus: “. . . . they sent Daphnis some of what they were eating (ἀπ’ῶν ησθίον)” (4.15.4).

- “Mark’s use of ἀρχὴ (1:1) to signal “the beginning” of the fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy (vv. 2-3) in the preaching of John the Baptist matches the use of ἀρχὴ in the romances.”

- So in Xenophon’s novel Apollo prophecies of sufferings to come but these do not happen immediately. Later in the story there is a pirate attack and the author announces that this was “the beginning” (ἀρχὴ) of the fulfilment of the prophecy (1.12.3). (cf. also Chariton, 1.6.5; Achilles Tatius, 1.3.1).

- “In addition, the oracle in Xenophon has a formal structure that parallels the passion predictions in the Synoptics (Mark 8:31; 9:31; 10-:32 and pars.).”

- The prophecy in Xenophon’s novella, like the prophecies of Jesus’ suffering in Mark’s Gospel, dwell on the details of the (many) sufferings to come and finish with a single line on the happy ending after it all. The same word for “suffering” is found in both, and even the equivalent of the expression of the hero or heroine “having suffered much” or “having endured many sufferings” (πολλὰ παθεῖν).

- This point brings to mind Dennis MacDonald’s comparisons between the suffering motif running in quite similar ways through Homer’s Odyssey and in Mark’s Gospel. It is a common theme of both popular and classical ancient literature.

- When we read in Chariton’s novel several times the expression of “hearing gladly”, and are reminded of Mark’s portrayal of Herod “hearing gladly” (ἡδέως [gladly] αὐτοῦ ἤκουεν) John the Baptist. The same novel gives us its opposite, when bad news is delivered, of the hearer “hearing despondently”.

- In a novel by Achilles Tatius we here echoes of the words attributed to Jesus accusing hypocritical priests of turning the Temple of God into a den of thieves when two chaste lovers who spent the night in the Temple of Artemis are falsely accused turning her temple into a temple of Aphrodite.

- One of the speeches of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark is noteworthy for the way the author breaks out from his narrative to directly address the readers, “Let the reader understand”. Similarly, the novelist Chariton is found to suddenly break out into addressing his readers in the last chapter of his novel, telling them they will find the remainder of the story much more pleasing and “cathartic” (8.1.4).

- Luke 12:9 contains a scene where a person is addressing himself as his soul, ψυχή, and we find the same device used by Dionysius in the same novel (3.2.9).

- The parable of the prodigal son in Luke 15:11-32 is also found not to be so uniquely “biblical” after one has read these romances.

- New Testament commentators have remarked that the scene of the old man running to greet his returning son is quite unrealistic, “beneath the dignity of an old man”, but the novels contain several comparable scenes. It was not so unusual to read of fathers or brothers running to meet their children/siblings returning after having been thought to be long dead (Chariton, 8.6.8; Longus, 4.23.1; 2.30.1; 4:36.3; Achilles Tatius, 1.4.1, 7.16.3).

- Longus even uses the expression of the returning one having been “lost but now found“.

- Joyful celebrations and dancing followed in at least one of these scenes (Longus)

- and the older brother who had remained at home also needed some reassurance — just as in Luke’s parable.

- Paul’s description of his home city, Tarsus, as being “no mean city” (Acts 21:39), and the defensive chant of the Ephesians, “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians” in response to Paul’s apparent threatening of the Temple’s economy, are both heard again in Achilles Tatius’s novel with respect to the city of Tyre (8.3.1) and in the same novel (1.11.5) and Xenophon’s (8.9.13).

- Paul was not unique in creating word images from the gymnasium (1 Cor. 9:24-27); the same imagery of only one competitor in a contest of many ever receives the crown in Chariton (1.2.2-4).

- The conventions used by Paul in his letters appear as well in the novels. (This is no surprise to anyone who has read Rosenmeyer’s “Ancient Epistolary Fictions” or my post on her work) —

- such as his closing greetings (Rom.16:3-16; Phil 4:21-22; cf Chariton 8.4.6),

- his authenticating signature (1 Cor 16:21; Phlm 19; cf Chariton 8.4.6),

- and arrangements for delivery and oral messages (Col 4:7-8; cf Chariton 4.5.1-2; 8.4.7-9; Xenophon 2.12.1; Achilles Tatius 5.21.1)

Encountering such details — and there are other overlaps that I have discussed in other posts, such as the popularity of a story of a crucifixion with the heroic victim managing to escape — happily helps unravel the sanctimonious mystique attached to the gospels that one might have imbibed from earlier exposure to the Bible.

But there is another illustration that Hock offers. In his ensuing discussion of the Parable of the Good Samaritan he opens up a quite different view of Jesus’ teaching from the one we learned about in Sunday School. By setting this parable alongside comparable facets in the ancient novels, one is forced to concede that the message of this parable was really a quite conventional aphorism in its day. For laypeople and scholars since, to revere its words as “revolutionary” or “countercultural” is to express one’s ignorance of its wider social and literary matrix.

But there is a second way to underscore the value of the romances, and that is to analyze more fully a single New Testament passage by bringing to bear a variety of parallels from the romances that cumulatively reveal the meaning of a passage — indeed, a meaning not previously proposed. . . . one place to begin is with the parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:30-37). (129)

Romancing the Good Samaritan

Recall the literary context of this parable. A lawyer had asked Jesus what was required to live forever. Jesus had the lawyer himself answer the question — the famous Doppelgebot: love of God and love of neighbour — and agrees with his answer. But the lawyer extends the encounter by asking another question, “Who is my neighbour?” Jesus answers with the following parable:

A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead.

A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side.

But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.’

Jesus then asked the lawyer who had acted as a neighbour to the victim. The lawyer responded, “The one who showed mercy”. Jesus admonished, “Go and do thou likewise.”

This parable has attracted enormous quantities of scholarship. Very little of it, I might suggest, relating it to the wider literary world from which it emerged.

Some results of this scholarship:

- the parable was known and told as an independent story before it appeared in the Gospel of Luke, the evidence for this being the “seam” that supposedly dislocates it from a natural place in the Gospel: the lawyer asks “Who is my neighbour?” but Jesus responds with “Who acted like a neighbour?”

- since the parable thus originated in a non-Lukan context, the question to be asked is, “What was its contextual origin?”

- its context related to Jesus’ concept of the Kingdom of God

- its context related to a general theory of parable as a metaphor (e.g. R. W. Funk who sees the Samaritan acting in a totally unexpected way, thus exaggerating the novelty of the parable’s message)

- its context related to a socio-political backdrop of peasant mentalité (e.g. Jesus’ audience would have sympathized with the brigands! – D. E. Oakman, 1992)

- many details of the parable have been explained well enough

- the historical danger of brigands on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho

- the differences between a priest and a Levite

- the hatred between Jews and Samaritans (e.g. J. Jeremias interprets the lawyer’s answer to Jesus’ question, “The one who showed mercy”, as a circumlocution to avoid uttering the hateful word ‘Samaritan’)

- the medicinal properties of oil and wine

- the purchasing power of two denarii . . . . .

But Hock sees a problem with all of these conclusions. None of them gives an adequate response “to what is clearly the focus of the parable — namely, the narrative detail lavished on the Samaritan’s actions . . . .” He drives home his point with reference to John Crossan’s literary analysis:

- Man travels to Jericho (v. 30a) (10 words)

- Brigands attack (v. 30) (10 words)

- Priest passes by (v. 31) (14 words)

- Levite passes by (v. 32) (12 words)

- Samaritan has compassion (v. 33) (10 words)

- Samaritan provides help (vv. 34-35) (50 words)

- Jesus asks who has acted as a neighbor (v. 46) (13 words)

Those fifty words devoted to the Samaritan’s actions, thus making it by far the dominant thought of the parable, deserve more than an analysis of the medicinal value of oil and wine.

No, what is called for is a conceptual understanding of the Samaritan’s actions as a whole. Scholars have been too content to use vague or modern categories to describe the Samaritan’s behavior — for example, “neighborliness” or “goodness.” But how would Jesus’ first century hearers or Luke’s readers have conceptualized this behavior? What term would they have used? On this question scholars are clueless. (p. 132)

Hock points to the romances for the answer to this question, reminding readers that these stories are replete with stories of travel and suffering misfortunes, very often brigand attack, along the way.

The most apposite word for the Samaritan’s behaviour that first century hearers would have used was φιλανθρωπία (philanthropia).

That is, philanthropy.

Hock reaches this conclusion as follows:

In Longus’ novel, Daphnis and Chloe, Longus narrates how his hero, Daphnis, was “saved from two dangers beyond all hope — the danger of brigands and the danger of shipwreck” (1.31.1).

Compare: In the literature attributed to Luke we have the story of an attack by brigands, the Good Samaritan, and the shipwreck experienced by Paul. When Paul was shipwrecked off Malta, the local inhabitants showed Paul “no ordinary φιλανθρωπία” (Acts 28:2). This φιλανθρωπία was demonstrated by warming the survivors by the fire, offering them hospitality till spring, supplying them with their provisions as needed for the remainder of their journey.

Plato is also on record as expounding the full nature of φιλανθρωπία. According to Plato there are three kinds of φιλανθρωπία:

- Extending greetings by offering their right hand when people meet;

- Being helpful to anyone who is unfortunate;

- Hosting dinners.

That is, φιλανθρωπία is characterized by “giving greetings, offering benefactions, and hosting dinners and promoting social discourse”.

Dio Chrysostom relates his own experience of shipwreck through which we see him invited into a home of a stranger, a hunter, given his every need by that hunter, and even invited to a wedding feast — all while preparing for his needs for the final leg of his journey. Dio’s hosts demonstrated φιλανθρωπία.

But the reverse is also true. There is also the misanthrope. Menander’s play Dyskolos demonstrates the attributes of the misanthrope. They are the opposite of the φιλανθρωπία as you might expect. In that play Knemon greets no-one, he offers no assistance to anyone in need, and refuses to accept an invitation to dinner.

But come back to the parable. The lawyer answered the question of Jesus asking who was the neighbour by saying, “He who showed mercy.” What has mercy to do with φιλανθρωπία?

The noun ἔλεος (“mercy”), it turns out, is often used as a synonym for φιλανθρωπία, as is already apparent from what the hunter said (Dio. Orat. 7.52: ἔλεηςα). In other words, the lawyer is not to be understood, as Jeremias thinks, as trying to avoid saying the hated word “Samaritan” and thus resorts to circumlocution; in fact, Jeremias’ interpretation distracts us from sensing the crucial clue to understanding the Samaritan’s behavior. Luke, who uses φιλανθρωπία in Acts 28:2, uses here the synonym ἔλεος for characterizing the Samaritan’s aid of someone who has fallen into misfortune. (134)

Other stories use the same terms as found in Luke’s parable in the same contexts: “half-dead”, “take care of”, “neighbour”. After discussing these Hock concludes:

It should now be clear that the parable of the Good Samaritan . . . is about φιλανθρωπία. The detailed description of the Samaritan’s coming to the aid of one who suffered a misfortune . . . : the use of the word ἔλεος to describe this conduct; and the use of other words that appear in philanthropic contexts . . . all point to conventions used in discussing φιλανθρωπία in the romances and elsewhere in Greco-Roman literature. (135)

Hock thus leads to the following points about this parable, given this literary analysis:

- The central character in the parable is the Samaritan — not Funk’s “man in the ditch” and certainly not Oakman’s “brigands”

-

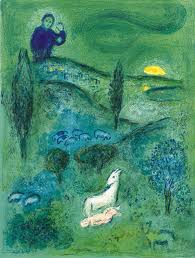

Longus discovers Daphnis (Marc Chagall) The hostility between Jews and Samaritans is not central to the parable as so many scholars assert. The victim is only implicitly (not necessarily) a Jew, and is primarily portrayed as anyone who is in need of philanthropic aid. Jesus’ Jewish audience is understood to have been shamed by the Samaritan as was the goat-herder Lamon shamed by the goat taking care of the baby.

- Viewing the Samaritan’s behaviour in terms of φιλανθρωπία leads to the conclusion, contra Funk, not that the Samaritan’s behaviour was novel, “frighteningly idealistic”, but merely that his behaviour was quite conventional — as demonstrated again by Dio’s account of his shipwreck.

- And what of Crossan’s seam that isolates the parable from its Gospel literary context? The unity of parable and context emerges more clearly in an ensuing discussion by Hock. . . .

It is worth quoting in full (with my own added bolded font for emphasis) . . . .

Chariton narrates a meeting between Callihroe and Dionysius that is illuminating in this regard. Dionysius has recently, of only briefly, seen the beautiful Callihroe, his newly purchased slave, but even in that brief encounter has fallen in love with her. Consequently, he wants to see and talk with her again, and at this next meeting he introduces himself as follows: “I am Dionysius, the leading citizen of Miletus and perhaps of all Ionia, widely known for piety (εὐσέβεια) and φιλανθρωπία . . . ” (2.5.4).

Dionysius is trying his best to impress Callihroe and thus emphasizes his high social status and his good moral character, the latter summarized in two words, one for his relation to the gods (εὐσέβεια) and the other for his behavior toward people (φιλανθρωπία). This pair of behaviors — piety toward the gods and love for mankind — echoes what Jesus expected the lawyer to say in order to gain eternal life. Though couched in the language of Jewish scripture, the lawyer’s summary is the same: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, strength, and mind, and your neighbor as yourself . . . .

In other words, this pairing of εὐσέβεια and φιλανθρωπία as a shorthand way for describing a good person, Samaritan or otherwise, is thereby conventional and, moreover, places the parable more coherently in its present literary context. The parable, it turns out, interprets the command to love the neighbor (Lev. 19:18) since, in the lawyer’s mind, the one word “neighbor” is not clear. The parable acheives clarity by understanding “neighbor” in the broadest possible terms, those implicit in φιλανθρωπία, or love of mankind. In other words, the lawyer now knows what is required of him: to be a good person he must, like Dionysius, love God unconditionally and be philanthropic. The latter requirement, we now know, is not some vague moral category, such as “the late Jewish ideal of the righteous man,” as C. Hedrick proposes, but a clear and specific moral obligation: accepting a limited number of responsibilities toward an unlimited number of people — specifically three responsibilities: greeting everybody, aiding anyone who is unfortunate, and being gregarious, as shown in attendance at symposia.

Even if this parable were picked up as a well-known story and placed secondarily in its present context in the Gospel of Luke, it nonetheless fits its context very well in the way it encapsulates the essence of a good person.

Conclusion

So Hock’s concluding message is that ancient novels are indispensable reading for New Testament scholars. Taking this post with my previous one that also shed light on the opening of the Gospel of Mark, Hock asserts that ancient novels are,

in a word, indispensable — for corroborating and clarifying any number of details in the New Testament and for gaining new insights into the central interests and claims of the New Testament, whether Christological or moral . . . .

The romances have pointed the way to seeing φιλανθρωπία as the implicit meaning of the Samaritan’s behavior. Consequently, we now know both what love of neighbor means and why we rightly put “good” before “Samaritan.” (137-138)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The author of g’Luke’, presumably the same author as Acts, has other references to Greek literature.

For example:

-“Luke’ 7.9 seems to parallel the ‘healing from a distance’ which is a characteristic of a Jewish story starring Hanina ben Dosa.

-“Luke” 7.32 uses similar words as a fable by Aesop.

In Acts at :

-26.14 we have ‘it hurts to kick against the goads” which is, apparently a quote frpm Euripides’ Bacchae 792-796

-17.28 refers to Epimenides; Aratus, Phaenomena 5

[I found these cites -somewhere- so I can’t vouch for their precision]

Author ‘Luke’ appears to be the most sophisticated writer of the 4 gospellers as far as the width of his reading is concerned.

The Gospel of John also contains many popular novelistic elements: http://vridar.wordpress.com/2007/08/05/novelistic-plot-and-motifs-in-the-gospel-of-john/

Yep, the more I read around this topic the more I think Thomas Thompson has got it right with his thesis of christianity and JC being the literary product of shared themes and motifs of the time and place.

Its christmas, nearly. I just shouted myself a used copy of TT’s “The Historicity of the Patriarchal Narratives”, due to arrive on 21 Dec.

Cool. That’s one less reason I have to feel pressure to post on that book! 😉

Does the NT, even though it borrows quotes from the OT, actually owe more to contemporary Hellenic literary traditions, than it does to Jewish literary traditions?

If so, is Christism not an offshoot of 1st c.. Judeanism (The Judeans seemed split between supporters of the Roman occupation of Judea who lined up behind the proRoman priests and aristos, and the masses who were more likely to support the populist antiRoman movements). but rather a creation of Greek culture that is using the Judean setting only as an exotic local for an otherwise typical Greek novel..

In such a melting pot of ideas and culture it would be difficult to begin to quantify degrees of cultural indebtedness from the various streams involved noting also that the constituent parts have borrowed from each are and the seams between them are fuzzy.

As an analogy consider Australian culture which whilst indivual in some ways owes much to its colonial forbear, Britain, its recent subservience to the US culture [for example a major chunk of our film, TV, politics, art, music emanates from the US] and on top of that add a fair sprinkling of Eastern Europen migration, recent Asian infux, particularly Vietnamese, and a few dantions from other cultures.

Who could precisely and with specificity say that a particular social ideology arising from Australia in the next few decades owes its origins to wherever and whomever and at what degree of measurement?

There is no denying the myth’s grounding in the Old Testament and (other) Second Temple literature. But “Jewish” and “Hellenistic” were not mutually exclusive terms. (Will post something from Hengel to demonstrate this sometime.)