Herman Detering posted on Facebook a link to the latest news of the Dutch pastor who has “come out” claiming that Jesus never existed. The news is an update on the fate of pastor Edward van der Kaaij who made the news a month ago in the NLTimes:

Jesus didn’t exist, but a “myth”, says banned pastor

That February NLTimes article said van der Kaaij was cointinuing to preach; I think the update alert from Herman Detering is telling us that that has changed. He is no longer able to preach.

Here are a few excerpts from the earlier February article:

“When someone reads Genesis 1 as a scientific explanation of how the world came into being, and concludes that the beginning was not about 13 billion years ago (as we know now) because the Bible states that it was about 70,000 years ago, then you do not properly understand the Bible,” explained van der Kaaij.

“The gospel is telling us a deeper truth, that goes far beyond the facts of life. That’s why I say: it did not happen like this and it is a fact that Jesus did not exist (I give a lot of proofs in my book to underline this).”

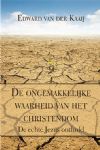

His book is De ongemakkelijke waarheid van het christendom (=The uncomfortable truth of Christianity). That link is to a Dutch bookseller. I copy here the Google machine translation of that site’s blurb (my own bolding throughout):

His book is De ongemakkelijke waarheid van het christendom (=The uncomfortable truth of Christianity). That link is to a Dutch bookseller. I copy here the Google machine translation of that site’s blurb (my own bolding throughout):

Jesus is a mythical, archetypal figure in a historical context. The uncomfortable truth gives a fresh perspective on faith and solves puzzles. So is the riddle of the three years of birth of Jesus addressed. You can find the answer to the question why nothing is known about the life of Jesus from his twelfth to his thirtieth year. How come the resurrection of Lazarus was not in the newspaper? What makes Jesus greater than the greats? At first glance, this book lays the ax to the roots of the faith, but on closer inspection the faith is richer.

Returning to the NLTimes February article:

“I am a Protestant and an important aspect of our belief is that the Bible is God’s Word (although written by men) and the starting point of our belief,” said van der Kaaij to NL Times. “So it is important to explain the Bible properly.”. . .

“The gospel gets more value when you read it according to what it is: a myth. Note that the word ‘myth’ does not have a negative meaning, on the contrary it is positive!” Continue reading “Mythicism Making Christianity More Meaningful”