| Stranger Every architect, too, is a ruler of workmen, not a workman himself. Younger Socrates Yes. Stranger As supplying knowledge, not manual labor. Younger Socrates True. Stranger So he may fairly be said to participate in intellectual science. Younger Socrates Certainly. Stranger But it is his business, I suppose, not to pass judgement and be done with it and go away, as the calculator did, but to give each of the workmen the proper orders, until they have finished their appointed task. Younger Socrates You are right. Statesman 259e-260a |

Who would ever have thought Plato and Karl Marx might have agreed on anything? Well, up to a point.

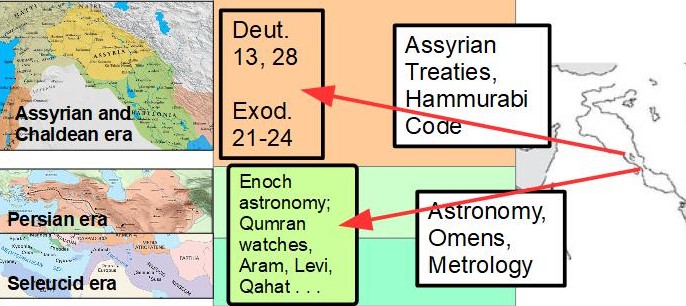

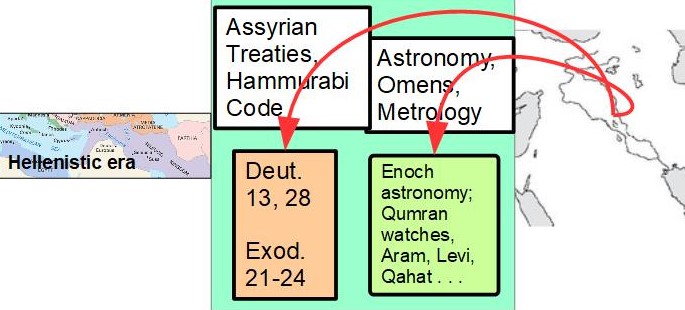

I have posted on Russell Gmirkin’s view that the Hebrew Bible, in particular its first five books (the Pentateuch), were influenced by Plato’s writings, especially his Laws, but the question that must be asked and answered is, Were Plato’s works ever used to attempt to change the real world?

I have posted on Russell Gmirkin’s view that the Hebrew Bible, in particular its first five books (the Pentateuch), were influenced by Plato’s writings, especially his Laws, but the question that must be asked and answered is, Were Plato’s works ever used to attempt to change the real world?

This post is a collation of passages I’ve taken from Plato’s Cretan City by the classicist Glenn Morrow demonstrating how Plato’s Laws were more than a mere theoretical exercise. I include references to what Morrow has to say about Plato’s influence beyond his writings.

From the Preface

No work of Plato’s is more intimately connected with its time and with the world in which it was written than the Laws. The other dialogues deal with themes magnificently independent of time and place, and Plato’s treatment of them has been recognized as important wherever human beings have thought about the problems of knowledge, or conduct, or human destiny. But the Laws is concerned with the portrayal of a fourth-century Greek city — a city that existed, it is true, only in Plato’s imagination, but one whose establishment he could well imagine as taking place in his day. (xxix)

Compared with the Republic, the Laws has the special value of presenting its principles not in the abstract, but in their concrete reality, as Plato imagined they might be embodied in an actual Greek city. (xxix)

There are references to Chaeronea in the quotes. Chaeronea is the site of the battle where Philip of Macedon ended Greek independence. It is usually taken as the event that divided Greek history from that of the Hellenistic Age.

Relevance in the territories conquered by Alexander the Great

If Plato was writing about a new colony, and the Greek age of colonization was long past, what relevance could there be for Samaria and Judea?

The establishment of colonies was a habit of long standing among the Greeks, less evident in Plato’s century than it had been in earlier days, but still regarded as the best way to deal with a surplus of population (707e) or with a discordant faction in a city (708bc). The great age of colonization during which the Greeks had spread themselves and their culture all over the Mediterranean area, from the northern shore of the Black Sea to the western coast of Spain, was a thing of the past; but the tradition was kept alive by the Athenian cleruchies and other more pretentious establishments in the fifth and fourth centuries, and another era of colonization was to begin soon after Plato’s time with the conquests of Alexander. Such new cities always started their political life with a set of laws especially designed for them, and a competent legislator was often called upon to advise the founder, or the sponsoring city, in the task of legislation. The great Protagoras was asked to draw up the laws for Pericles’ ambitious colony of Thurii in southern Italy; and Plato himself, according to one tradition, was invited to legislate for the new city of Megalopolis in Arcadia set up after the defeat of Sparta at Leuctra. We see, therefore, that the Athenian Stranger [a key participant in the conversation in the Laws] is in a historically familiar situation, and the conversation he carries on with his companions is but an idealized version of the discussions that must have taken place on countless occasions among persons responsible for establishing a new colony.

Furthermore, it was a situation that might confront Plato or a member of the Academy at any time. Plato’s deep and lifelong interest in politics, in the broadest sense of the term, is evident from the large place that the problems of political and social philosophy occupy in his writings. His theories of education, of law, and of social justice are inquiries carried on not merely for their speculative interest, but for the purpose of finding solutions to the problems of the statesman and the educator. It may well be affirmed, when we view Plato’s work as a whole, that he was more concerned with practice than with theory. (3f – for the additional detail and sources found in the original footnotes check out full text online at archive.org)

One might even imagine that Alexander and Aristotle would send re-educators to Samaria after its rebellion to advise more loyal persons on the best way to constitute an ideal state.

One footnote that I must add here:

= Plato only came to philosophy through politics … Philosophy was originally, for Plato, nothing but hindered action.

“Platon est en effet, contrairement à ce qu’on croit souvent, beaucoup plus préoccupé de pratique que de théorie.” Robin, Platon, Paris, 1935, 254. Similarly Dies, in the Introduction to the Bude edn. of the Republic, v: “Platon n’est venu en fait à la philosophie que par la politique . . . La philosophie ne fut originellement, chez Platon, que de l’action entravée.” But we must not suppose that for Plato theory was a substitute for action. Indeed the scientific statesman, he says in Polit. 260ab, cannot be content with theoretical principles alone, but must supplement them with directions for action . . . Cf. also Phil. 62ab.

Plato Meddling in Politics

Did Plato do anything personally to try to make a difference?

From these statements we must infer that one purpose of the Academy which Plato founded and directed during these years, perhaps at times its chief purpose in his eyes, was the training of statesmen, or legislative advisers, imbued with the insights of philosophy. How did the Academy prepare its members for the practical work of legislation and constitution making? By the study of mathematics and dialectic, of course, for the statesman must first of all be a philosopher; but also, it seems clear, by the study of Greek law and politics. It must not be forgotten that in the Republic the education of the philosopher guardians includes more than the abstract sciences. The fifteen years of mathematics and dialectic are to be followed by fifteen years of service in subordinate administrative posts before the candidate for guardianship is completely trained. The Academy was not a polis and it could not offer its students the advantages of actual experience in office; but it could encourage them to gain a wide knowledge of the history and characters of actual states. This it certainly did, attracting students from all parts of the Greek world, and therefore possessing within its own membership considerable resources for a comparative study of laws and customs. Plato himself had traveled . . . (p. 5)

and further,

On one occasion that we know of Plato had himself taken a hand in politics, when the death of the elder Dionysius of Syracuse in 367 had brought his young and promising son to the throne. Dion, the uncle of the young tyrant, had become Plato’s devoted follower during the latter’s earlier visit to Syracuse, and he now saw an opportunity of bringing about a political reform. He persuaded the young tyrant to invite Plato to Syracuse, and himself sent an urgent request that Plato should come and take the young man’s education in hand. Plato acceded, but with some reluctance, he tells us, because he feared the young Dionysius was not sufficiently stable in character to make promising material for a philosophical ruler; but his doubts were outweighed by his friendship for Dion, and by his feeling that he should make an effort, at least, when there was an opportunity of putting into effect his ideas of law and government. This mission at first seemed likely to succeed, and Plato may have collaborated with Dionysius on legislation for the resettlement of the Sicilian cities of Phoebia and Tauromenium. But the court at Syracuse was filled with supporters of the tyranny, opposed to reforms of the sort Plato and Dion had in mind. . . . This history, unhappy though its outcome, shows that Plato’s principles were meant to be applied to the actualities of fourth-century politics. Some prominent members of the Academy later took part (though Plato refrained) in Dion’s later expedition against Syracuse and were associated with him in his brief period of power after the overthrow of Dionysius. These later events would only confirm the reputation that the Academy had as a center of political influence. (7)

The rumours and traditions…

There are other evidences of the influence of Plato and his Academic colleagues on fourth-century states and statesmen. There is a tradition that Plato was invited by the Cyrenians to legislate for them; and another . . . that he was asked to draw up the laws for the Arcadian city of Megalopolis. Both these invitations Plato declined; but in the second case he seems to have sent Aristonymus to act in his stead. Plutarch names several members of the Academy who were influential as legislators or advisers to statesmen and rulers. Aristonymus was sent to the Arcadians, Menedemus to the Pyrrhaeans; Phormio gave laws to Elis, Eudoxus to the Cnidians, and Aristotle to the Stagirites. Xenocrates was a counsellor to Alexander; and Delius of Ephesus, another Academic, was chosen by the Greeks in Asia to urge upon Alexander the project of an expedition against the Persians. Thrace, he says, was liberated by Pytho and Heraclides, two Academics; they killed the tyrant Cotys, and on their return to Athens were feted as “benefactors” and made citizens. Athenaeus tells us, on the authority of Carystius of Pergamum, that Plato sent Euphraeus of Oreus as adviser to King Perdiccas of Macedon; later Euphraeus seems to have become the champion of the independence of his native city, and was slain when the city was reduced by Philip. Hermeias, the tyrant of Atarneus and friend of Aristotle, may have studied in the Academy; and the Sixth Epistle is a letter supposedly written by Plato commending to him two students of the Academy who are coming to live near Atarneus. Finally, at Athens there must have been many persons prominent in public life, like the generals Chabrias and Phocion, who were former students of Plato. We know that the orator and statesman Lycurgus, who came into power after Chaeronea, was such a former student; and the legislation of Demetrius of Phalerum, at the end of the century, shows clear traces of Plato’s influence, through Aristotle and Theophrastus.

Some of this evidence is of questionable value, but its cumulative effect is to show that the Academy was widely recognized as a place where men were trained in legislation, and from which advisers could be called upon when desired. It is easy therefore to understand why Plato should have devoted the closing years of his life to the composition of such a painstaking piece of hypothetical legislation as the Laws. It expresses one of the main interests of his philosophical mind; and it may also have been intended as a kind of model for use by other members of the Academy. Plato had indeed set forth in the Republic the principles that should guide a legislator, but they are expounded in very general terms, with little specific legislation. In the Laws, however, the author descends into the arena of practical difficulties, and we can see why he thought it necessary to do so. For if the ideal, or any worthy imitation of it, is to be realized, it has to be exemplified concretely—among a people living in a specific setting in time and place, possessing such-and-such qualities and traditions. This translation of his political ideal into the terms of fourth-century Greek politics was, as he says, “an old man’s sober pastime” (685a, 712b), but it was a form of amusement that he must have thought would give guidance to actual statesmen. (8ff)

Plato, like a Political Demiurge

Plato’s conception of the legislator’s task in bringing his ideal into existence becomes clearer if we consider the analogous work of the demiurge in ordering the cosmos as described in the Timaeus. In both cases the craftsman must be attentive not only to the design he wishes to realize, but also to the materials in which it is brought about. It may seem to some persons unworthy of the divine Plato to occupy himself with such things as the laws of inheritance, the registers of property, the procedures of election, the regulation of funeral expenses; or with the organization of songs, dances and athletic contests ; or with questions of drainage and water supply. A large part of the Laws consists of just such materials—materials on a par, certainly, with the discussion of respiration, the mechanism of vision, or the functioning of the liver and spleen that we find in the Timaeus. For the cosmic demiurge such attention to his materials was necessary, if he was to operate on the world of Becoming and remold it in the likeness of the Ideas. Similarly the political demiurge cannot neglect the understanding of his social and human materials if he is going to construct a state that resembles the ideal. Just as the world craftsman in the Timaeus has to use the stuff that is available, with its determinate but unorganized and irregularly co-operating powers, so Plato has to use the Greeks of his day, with their traditions of freedom and respect for law, and their fallible human temperaments. They are not always the best adapted to his purpose, but as a good craftsman he selects them carefully and handles them with skill, so as to create a likeness as close as possible to the ideal. (10)

When Rome faced Carthage

Plato informed details of Rome’s demands on Carthage?

Was Plato’s condemnation of sea power later used by the Romans to justify the destruction of Carthage? “… [T]he Roman offer that the Carthaginians should settle at least eighty stades from the sea corresponds exactly to the suggestion of the Laws.” Momigliano… (100)

Compromise and Distortions

Athenian institutions were a distortion of Plato’s recommendations?

There is a closer parallel between Plato’s program for the agronomoi and the two-year term of ephebic training introduced at Athens, or drastically reformed after the battle of Chaeronea, and it is not unlikely that his proposals had some influence upon at least the later form of this institution.87

87 . . . It is generally agreed that there was a reorganization about 335, and it is possible that the Laws left its mark upon it. The account Aristotle gives of ephebic training in his day (Const. Ath. xlii, 3-4) contains some features that resemble Plato’s program for the agronomoi, but it also exhibits some striking differences, and these have usually not been noted. The Athenian program was for youths just turned eighteen; Plato’s is to take place somewhere between the ages of twenty-five and thirty. The former was obviously a preparation for citizenship and the military obligations that citizenship involved at Athens; whereas Plato’s seems rather a preparation for office, of men whose full citizenship had been attained some years before. Of course ancient readers, like some modern ones, may have overlooked these differences in purpose and in details; but if the Athenian program reflects Plato’s ideas, it does so dimly and with distortion. (190)

Guardians of the Law in the Real World

Continue reading “Could Plato Really have Influenced Judaism and the Bible?”

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.

I have been posting on points of interest in Seth Sanders’ From Adapa to Enoch: Scribal Culture and Religious Vision in Judea and Babylon and have reached a point where I cannot help but bring in certain contrary and additional perspectives from another work I posted on earlier, Russell Gmirkin’s Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.