This post is an extension of an earlier one, Jerusalem unearthed.

Israel Finkelstein describes Jerusalem’s rise to power in the seventh century b.c.e. as a result of integrating itself within the Assyrian imperial economy after the fall of Samaria. He writes of Jerusalem being the capital of a politically integrated kingdom of Judea.

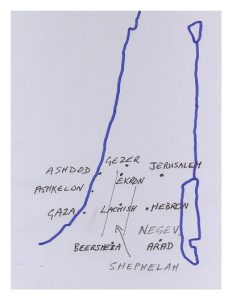

Thomas L. Thompson likewise argues that Jerusalem rose to power with Assyria’s blessing. Jerusalem did not extend its influence to the north or any other Assyrian conquered areas, but to the southwest and south, the Shephelah and the Negev. Further, Judea was not a politically integrated kingdom or nation, but was dominated politically by city-state Jerusalem imposing its hegemony over other city states like Hebron.

Jerusalem’s population multiplied greatly at this time, and for the first time “acquired the character of a regional state capital. One must doubt Jerusalem’s capacity for such political aggrandizement at any earlier period.” (Thompson, p.410)

Jerusalem’s growth

For background to this, see earlier post, Jerusalem unearthed.

Commercial rival Lachish had been destroyed, never to be rebuilt, and this opened up the possibility of more of the southern area’s resources to Jerusalem.

But the Assyrians had also, led by Sennacherib, diminished Jerusalem’s influence when they invaded parts of Judea.

Thompson suggests that given Samaria had been a longstanding enemy of Jerusalem, it is unlikely that refugees from Samaria would have sought refuge in Jerusalem. They would more likely have gone to allies in Phoenicia. Moreover, Jerusalem would have been drawn into “the direction of a hopeless confrontration with Assyria” had they accepted large numbers of Samarian refugees.

Here Finkelstein and Thompson part. Finkelstein sees Jerusalem’s population swelling primarily as a result of refugees from the northern kingdom rather than those of the Shephelah area. Finkelstein argues for cultural-historical affinities between the peoples of the northern and southern “kingdoms” but Thompson sees no archaeological evidence for these. Thompson sees the various geographical regions of Palestine as a hotch-potch of ethnic and cultural groups until the Persian era at the earliest.

The size of Jerusalem — a great city in the seventh century — time meant it could no longer be economically sustained “solely by the Jerusalem saddle and the Ayyalon Valley.” Thompson sees Jerusalem as a city-state compelled to secure itself by dominating the resources of neighbouring areas to the south and south west.

Comparing Ekron — a mirror to Jerusalem’s rise?

At the same time Ekron expanded its influence to dominate the coastal plain lands and cities. Ekron was able to do this as a result of cooperation with the Assyrian empire. Ekron served Assyria’s interests by establishing itself as a centre of a vassal state in Judaea.

Assyrian reorganization of Judea under Jerusalem

Assyria destroyed Lachish and other towns of the Shephelah and these were not resettled. “Rather, during the seventh-century, Judaea, and with it the Shephelah, was reorganized around a number of new fortified towns, apparently subject to Jerusalem . . . ” (Thompson, p.411)

According to Thompson, Jerusalem’s growth and expansion was that of an imperial city state over subject peoples and cities like Hebron. Unlike the erstwhile northern kingdom of Israel, Judea was not a politically integrated united kingdom. It maintained its hegemony as an imperial city state only.

Jerusalem expanded southward to the Judaean highlands, the Shephelah and perhaps the northern Negev. “It is unlikely, however, that the exercise of this warrant was carried out in opposition to the firmly established Assyrian authority in the region.” (Thompson, p.411)

Finkelstein concurs that Jerusalem benefitted from cooperation with Assyria, but sees Judea becoming an integrated kingdom, not merely an area under the hegemony of a newly giant city-state. “The question is, where did this wealth and apparent movement toward full state formation come from? The inescapable conclusion is that Judah suddenly cooperated with and even integrated itself into the economy of the Assyrian empire.” (Finkelstein, p. 246)

Where Finkelstein and Thompson part

Finkelstein’s interpretation of the evidence hinges on his belief that much of the biblical literature, in particular the history of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah beginning with the United Kingdom of David and Solomon, was the product of the pre-exilic Kingdom of Judah.

Thompson instead argues that the themes of the biblical literature find no basis of origin before the Persian period. The archaeological evidence is against the existence of a united kingdom of Israel or large-scale influx of a new ethnic-cultural-religious group dominating Palestine in the Iron Age. It is not until the Persian era that Palestine is united politically and religiously, and this with the migration of a new group of peoples at the behest of the Persian imperial authority.

Such a development [the creation of a Jerusalem led “nation-state”] came about only with the ideological and political changes of the Persian period, centered around the Persian supported construction of a temple dedicated to the transcendent elohe shamayim, identified with Yahweh, the long neglected traditional god of the former state of Israel, who, in his new capital at the center of the province of Yehud, might, like Ba’al Shamem of Aramaic texts, be best described as a Palestinian variant of the Neo-Babylonian divine Sin and of Persia’s Ahura Mazda. (Thompson, pp.411-2)

I think that both Thompson and Finkelstein would agree that history tells us as much or more about those who wrote it as it does about the past.

Finkelstein sees the biblical history being concocted by propagandists of King Josiah’s court to justify his presumed interest in expanding his kingdom north to incorporate Samaria. This history supposedly exaggerated events of the past to justify Josiah’s ambitions:

Yet it is clear that many of the characters described in the Deuteronomistic History — such as the pious Joshua, David, and Hezekiah and the apostate Ahaz and Manasseh — are portrayed as mirror images, both positive and negative, of Josiah. The Deuteronomistic History was not history writing in the modern sense. It was a composition simultaneously ideological and theological. (Finkelstein, p. 284)

Personally I don’t understand why such propagandists would create negative images of Josiah.

While agreeing that the biblical history was ideological and theological, Thompson sees the biblical history being concocted by propagandists among the the leaders of those deported by the Persians to settle in Palestine. This history was apparently inspired by themes of settlement among an indigenous population who did not welcome the newcomers, of a new state arising out of peoples migrating from Mesopotamia, and even from a (Persian created) political entity stretching from Euphrates to the Nile — compare Genesis 15:18 and 1 Kings 4:24.

I consider this the more plausible explanation.