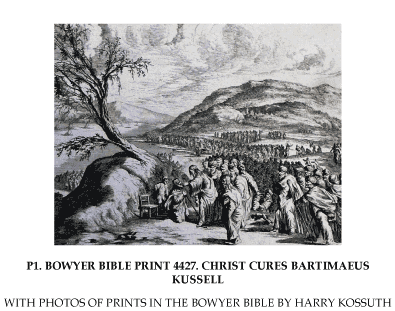

Here beginneth the lesson. The Gospel of Mark, chapter 10, verses 46 to 52, in the original King James English:

And as [Jesus] went out of Jericho with his disciples and a great number of people, blind Bartimaeus, the son of Timaeus, sat by the highway side begging.

And when he heard that it was Jesus of Nazareth, he began to cry out, and say, Jesus, thou Son of David, have mercy on me.

And many charged him that he should hold his peace: but he cried the more a great deal, Thou Son of David, have mercy on me.

And Jesus stood still, and commanded him to be called.

And they call the blind man, saying unto him, Be of good comfort, rise; he calleth thee.

And he, casting away his garment, rose, and came to Jesus.

And Jesus answered and said unto him, What wilt thou that I should do unto thee? The blind man said unto him, Lord, that I might receive my sight. And Jesus said unto him, Go thy way; thy faith hath made thee whole. And immediately he received his sight, and followed Jesus in the way.

The author of this passage appears to have inserted a couple of clues to alert the observant readers that they will miss the point entirely if they interpret this story literally. It is not about a real blind man who was literally healed by Jesus. But I’ll save those clues for the end of this post. (As Paul would say, “Does God take care for oxen and blind beggars? Or saith he it altogether for our sakes? For our sakes, no doubt, this is written.”)

There are many commentaries on this passage and I have posted about Bartimaeus a few times now. But this time I’ve just read something completely different so here’s another one. (Well at least the bit about why Jesus stood still will be different, yes?)

There are many commentaries on this passage and I have posted about Bartimaeus a few times now. But this time I’ve just read something completely different so here’s another one. (Well at least the bit about why Jesus stood still will be different, yes?)

Seeing

Mark uses different words for “sight” and “seeing”. Of the word used in “receive my sight” and “received his sight” is anablepo — “look up” — which Karel Hanhart says, the the Gospel of Mark (6:41; 7:34; 8:24; 16:4), “means to look at life with new eyes opened by faith”.

Many scholars agree that this usage is related to the two “blind receiving sight” stories (8:22-26; 10:46-52) which offset the central section of the Gospel and highlight the need of conversion if one is to understand Jesus’ “way to the cross” (cf. 8:34). (p. 124, The Open Tomb)

Hanhart, like a few other scholars who also identify Mark’s theme of the Way or Second Exodus in Isaiah, believes Mark is evoking passages such as Isaiah 42:16 Continue reading “Blind Bartimaeus in the Gospel of Mark: Interpreted by the Gospel of John?”