What’s in a name?

And because of my father, between the ages 7 through 15, I thought my name was “Jesus Christ.” He’d say, “JESUS CHRIST!” And my brother, Russell, thought his name was “Dammit.” “‘Dammit, will you stop all that noise?! And Jesus Christ, SIT DOWN!” So one day I’m out playing in the rain. My father said “Dammit, will you get in here?!” I said, “Dad, I’m Jesus Christ!”

–Bill Cosby

In his new book, Jesus: Evidence and Argument or Mythicist Myths? (which Jim West with no trace of irony calls “excellent”), Maurice Casey makes it abundantly clear that Neil and I should get off his lawn. We should also slow down and, for heaven’s sake, turn out the lights when leaving a room.

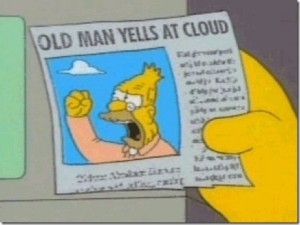

Maurice Casey: Old Yeller

Since my chief purpose here is not to make fun of such a charming and erudite scholar as Dr. Casey, I’ll say just one thing about the shameful way a famous scholar lashes out at amateurs on the web. Lest any reader out there get the wrong idea, my first name is not Blogger. Same for Neil.

I will instead, at least for now, ignore the embarrassing, yelling-at-cloud parts of this dismal little book and focus on Mo’s evidence for the historical Jesus.

If I had a hammer

“I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”

–Abraham Maslow

Casey, you will recall, has written several books on biblical studies. He’s justly recognized as an expert in the Aramaic language. In fact, he is probably the foremost living expert on Aramaic, especially with respect to its historical roots, its evolution, its variants, and its use in first-century Palestine. I own most of his books on the subject, and although I disagree with many of his dogmatic conclusions, his basic research is thorough and generally reliable.

The problem I have with Casey is that his prodigious knowledge of Aramaic causes him to see everything in the New Testament from that perspective. He frequently reminds me of Catherwood in the Firesign Theatre’s “The Further Adventures of Nick Danger,” who, upon returning from the past in his time machine, shouts:

I’m back! It’s a success! I have proof I’ve been to ancient Greece! Look at this grape!

Continue reading “Casey’s Hammer: How Monomania Distorts Scholarship (Part 1)”