I received an email a few weeks ago [4 Jan. edit: make that a few months ago], in which the sender asked some questions that deserve an extended response. If and when I have the time, I will add more to this post, but I at least would like to start with a broad outline of my understanding of the history of life-of-Jesus research — both in the ways it was actually conducted and in the ways it is currently “remembered.”

Here’s the text of the email:

Hello, I am a fan of Vridar, and I found a comment that you posted in an article that you wrote. The article is at https://vridar.org/2014/05/14/

what-do-they-mean-by-no-quest/ . The comment that you made is “One thing that struck me recently while reading and re-reading material related to the Quest, including books from the 19th and early 20th century, is how often authors will state matter-of-factly that “of course” the gospels aren’t biographies. This whole gospels == biographies debate seems rather new and not well argued. But since believing that they are biographies is useful for their narrow purposes, it has become the consensus position among today’s scholars.”

I have a few questions regarding this comment.

1. What books from the first Quest, say plainly that the gospels aren’t biographies?

2. Do they know of Greco-Roman biographies?

3. Do they list reasons why they aren’t biographies?

4. How is the current understanding not well argued?Thank you for taking the time to read this. I am eagerly anticipating your response.

Before continuing, I just want to say I’m stunned that nine years have passed since I wrote that post. Where does the time go?

What Biography?

First of all, the general consensus in the 19th century held that the canonical gospels contained biographical material, but were obviously not like modern biographies. Many modern scholars who write on this subject annoyingly imply that this assessment is somehow new. Nobody thought that was the case, and nobody confused popular biography or hagiography or legendary biography with modern biography.

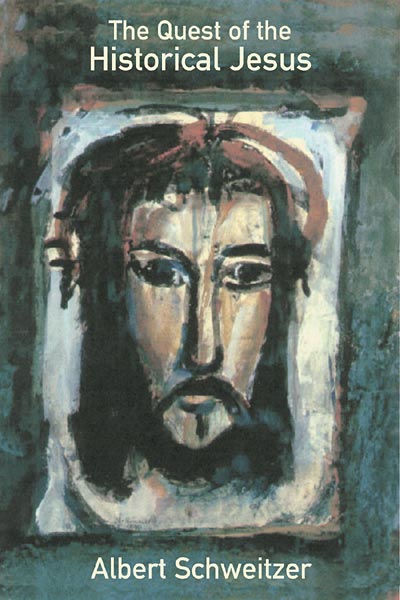

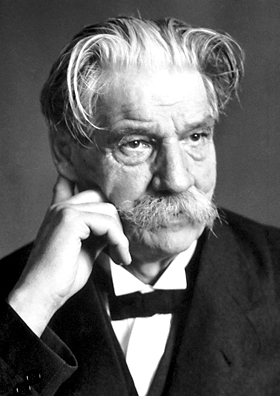

The question was simply: Can we use the materials at hand — namely, the aforementioned biographical material — to create a broad historical outline of Jesus’ life. In some cases, they referred to such a sketch as a “historical biography” or “scientific biography.” However, as we know from reading Albert Schweitzer and William Wrede, the authors of these “lives of Jesus” made two fatal errors: (1) assuming that Mark, as the first written gospel, could be trusted as an unbiased historical account, and (2) psychologizing Jesus far beyond the limits of reasonable conjecture.

What Quest?

Second, the somewhat sensational title of the English translation of Schweitzer’s A History of Life-of-Jesus Research, (Eine Geschichte der Leben-Jesu-Forschung), colors the way we perceive the task at hand. You may suspect that I’m overstating the case, but I think this change of focus is crucial. In the original German, the title — and in fact, the entire work — centers on the scholars and their research. Schweitzer had intended the original title, Von Reimarus zu Wrede, as the attention grabber, but in subsequent editions it was dropped in favor of the subtitle, and in the German world is referred to as History of Life-of-Jesus Research (without the indefinite article).

In English, the very word “quest” evokes a kind of mystic medieval landscape — a verdant, rolling countryside populated with devout knights-errant finding venerated objects, killing mythical beasts, fighting rivals, and saving damsels in distress. In this case, the aim of our quest is not piety or glory, but instead the Jesus of history. Schweitzer’s survey of scholarly research has thus become a romantic historical mission. Continue reading “How Did Scholars View the Gospels During the “First Quest”? (Part 1)”