Not all minimally counterintuitive concepts are good candidates for interesting story material. A potato that vanishes whenever someone looks is soon a forgotten idea; but a potato that can talk to you has potential for many creative plot lines.

In the previous post we saw how certain minimally counterintuitive concepts can have the potential to be strikingly memorable and shared in wider groups. By a “minimally counterintuitive concept” we mean a concept that violates only one or two attributes of that our basic mental tool kit would lead us to expect: e.g. a dog that talks (talks and thinks like a human) is more memorable and interesting as a focus of a story than a dog that experiences time backwards, is born or a rhino that mated with a bullfrog, sustains itself on graphite, speaks Latin and changes into cheese on Thursdays. The latter dog becomes a laundry list of oddities and even begins to lose any identity as a dog at all. A living animal that has the communication faculties of a human is distinctly notable, however.

But not all minimally counterintuitive concepts serve well as religious ideas. Justin Barrett’s chapter, “Gods” (in Religion, Anthropology, and Cognitive Science), proposes that the best religious belief systems focus around minimally counterintuitive concepts that are intentional agents. Recall our most relevant mental tool kit devices:

-

- Naive Physics Device (physical objects cannot move through each other; need to be supported or will fall….)

- Agency Detection Device (automatically tells us that self-propelled and goal-directed objects are intentional agents)

- Theory of Mind Device (actions are guided by beliefs, by wishes to satisfy desires….)

- Naive Biology Device (animals bear young like themselves; they are organic matter….)

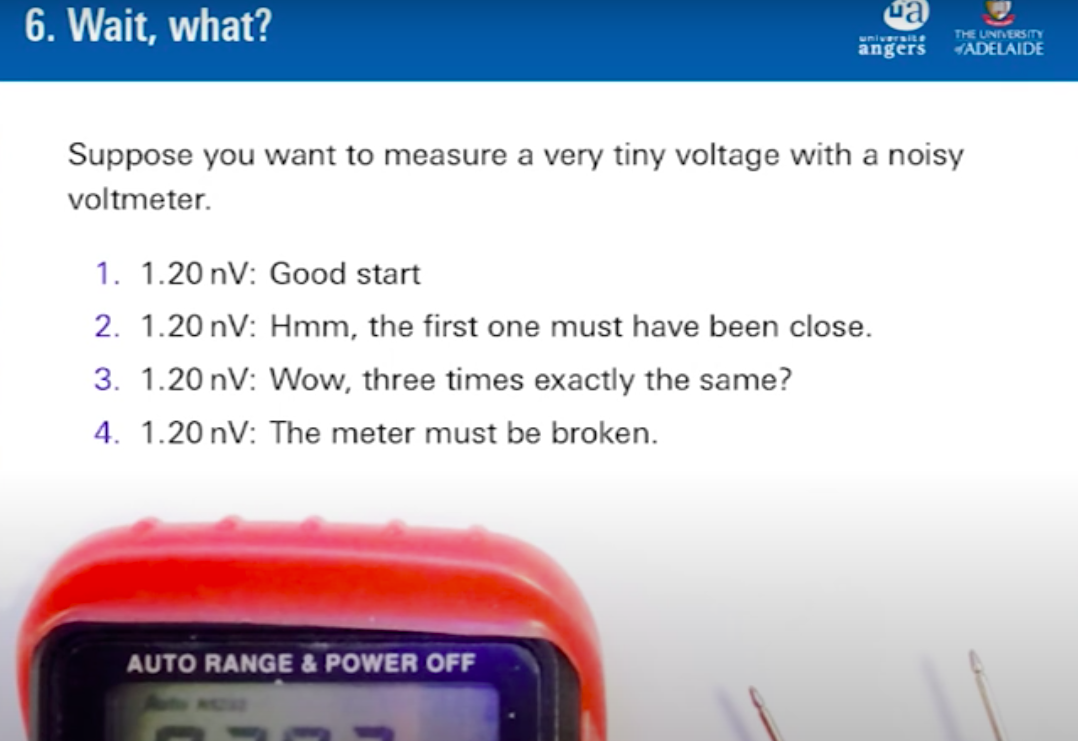

Justin Barrett points out that researchers have demonstrated by means of experiments involving “moving dots on a computer screen and other artificial displays” that the “agency detection device” is “touchy” or “hyperactive”.

Justin Barrett points out that researchers have demonstrated by means of experiments involving “moving dots on a computer screen and other artificial displays” that the “agency detection device” is “touchy” or “hyperactive”.

Anthropologist Stewart Guthrie has suggested that our tendency to find agency (especially human-like agency) around us has arisen for survival reasons. Historically, our best opportunities for survival and reproduction and our biggest threats were other agents. So, we had better be able to detect agents. Better to guess that the sound in the bushes is an agent (such as a person or tiger) than assume it isn’t and become lunch. If it turns out you were too cautious (about the wind blowing in the brush, for instance), not much is lost (Guthrie, 1993). This hypersensitive agency detection device (or HADD) produces non-reflective beliefs that agency is present and then the Theory of Mind tool generates non-reflective beliefs about beliefs, desires, perceptions, and so forth of the alleged agent (Barrett, 2004).

Imagine viewing simple movies of the following sort:

(1) Two small squares are sitting in a line, separated by several inches. The first square (A) moves in a straight line until it reaches the second square (B), at which point A stops moving and B starts moving along the same trajectory.

(2) Two small squares are sitting in a line, separated by several inches. The first square (A) begins moving in a straight line towards the second square (B). As soon as A gets close to B, B begins moving quickly away from A in a random direction, until it is again several inches from A, at which point it stops. A continues all the while to move straight towards B’s position, wherever that is at any given moment. This pattern repeats several times.

Objectively, all that is happening in such movies is the kinematics described above. Perceptually, however, a striking thing happens: in the first movie, you see A cause the motion of B, and in the second movie, you see A and B as alive, and perhaps as having certain intentional states, such as A wanting to catch B, and B trying to escape . . . .

I think we can all accept this point. We know how easy it is to imagine unusual sounds in a still house are evidence of an intruder, “or “how light patterns on a television screen are people or animals with beliefs and desires”. Barrett cites an article by Scholl and Tremoulet [link is to pdf] addressing the question. Example in the side box.

An agency detection device is quickly activated to explain a wisp of fog or blowing sheet on a clothesline as a person, even a ghost, for a moment.

An agency detective device, in particular a hyperactive one (as they tend to be), come to the fore to “explain” events around us:

An example of an event that may trigger agent detection might be the following. When walking through a reportedly haunted castle, a decorative sword falls and narrowly misses cutting off your arm, just after you scoffed at the idea of ghosts. (Foolish mortal!) Given that a physical object appeared to have moved in a way that was not readily explained by the non-reflective beliefs of Naïve Physics (because inanimate objects cannot move themselves), and the movement seemed to be goal directed (to answer your skeptical comment), your HADD might detect agency at play. HADD searches for a candidate agent. As the sword is not an agent in its own right, a non-reflective belief that an unseen agent must have moved the sword arises from HADD. Connecting this non-reflective belief in present agency to the reflective proposition that ghosts inhabit the castle makes acquisition of a reflective belief in a ghost perfectly natural given the circumstances. The sword falling is an event that HADD might detect as agency.

Barrett adds “physical traces” to the list of things an agency detection device seeks to explain. The word “traces”, though, in my estimation, begs the question because it assumes a causal agent within the very definition of the word. So we have arguments over whether crop circles are caused by space aliens or human pranksters. I would prefer “physical phenomena” to “traces” — many are easily explained but we do come across even natural phenomena that look strange and we are easily led to imagine (erroneously) intelligent agents as their cause.

Here we get into a very messy realm. Many Bible believers are convinced that they see “traces” or evidence of fulfilled prophecy, for example, in their holy writings. Others see “miraculous” gematria at work. And so forth. We know where this agency toolbox leads in these contexts.

Another context Barrett pinpoints as significant is what he calls “contextual” — meaning that if we walk alone through a tree-thick park as evening descends we are more likely to “detect” false-positive indicators of a mugger waiting to surprise us than we would in the fresh sunlight of a morning.

Another opportunity for the agency detection device to come to the fore is in a religious ceremony. (Though again, are we not here begging the question somewhat? But we do see an opportunity for reinforcement, certainly.)

The salience of explicit, reflective expectations for witnessing agency increases agency detection as well. Told that a particular religious event (e.g., a ritual or petitionary prayer) will cause a god to act in a particular way, I would be primed to find seek confirming evidence of the god’s activity.

The salience of explicit, reflective expectations for witnessing agency increases agency detection as well. Told that a particular religious event (e.g., a ritual or petitionary prayer) will cause a god to act in a particular way, I would be primed to find seek confirming evidence of the god’s activity.

McCauley and Lawson observe that many religious rituals in which a god or representative of a god performs an action (e.g., as when a priest marries a couple, or a minister baptizes a person, or an elder initiates a youth), the ritual and surrounding trappings tend to be more elaborate and more emotional. One reason offered for this correlation is that the heightened sensory pageantry and resulting emotional arousal impresses upon the participants and observers that the gods are really acting because of or through the ritual (McCauley & Lawson, 2002). This observation leads me to speculate that the additional sensory pageantry excites HADD (perhaps through general arousal) and, in some cases, provides more potential events and traces that might be attributed to the gods.

Yes, we can quickly override those mental temptations to impute agency to a sound from a tree branch moving in the wind, a sound of our house timber shrinking in the cool of the night, but we are still left with our propensity to quickly imagine an unknown and intentional agent being responsible for these sounds, etc.

Even though a single HADD experience might be overridden and not result in a reflective belief, these experiences will be remembered and cumulatively lend plausibility to reflective belief.

To illustrate this dynamic in another way, compare three people:

1. A person walks through a wood after having been told that forest spirits dwell in it. Something ambiguous happens prompting this person to have HADD experiences. The experiences will be likely to reinforce the belief in forest spirits.

2. A second person walks through a wood and has the same HADD experiences as the first person but does not successfully identify an agent that accounts for them, and so does not form a reflective belief in an agent. But after the fact, the person hears that forest spirits dwell in that stretch of woods. Memories for the HADD experiences might be triggered and evaluated as evidence for reflective belief.

3. A third person walks through the wood, having heard that it is populated by forest spirits but has no HADD experiences at all.

Clearly, the first two people are considerably more likely than the third to form a reflective belief in forest spirits. HADD would play a pivotal role in belief formation or encouragement.

It might be that HADD rarely generates specific beliefs in ghosts, spirits, and gods by itself, and hence does not serve as the origin of these concepts. Nevertheless, HADD is likely to play a critical role in spreading such beliefs and perpetuating them.

Next — how the agency detection tool connects events in our lives, and how we live our lives, with unseen agents.

Barrett, Justin L. 2007. “Gods.” In Religion, Anthropology, and Cognitive Science, edited by Harvey Whitehouse and James Laidlaw, 179–207. Durham, N.C: Carolina Academic Press.

Scholl, Brian J, and Patrice D Tremoulet. 2000. “Perceptual Causality and Animacy.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 4 (8): 299–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01506-0.

Like this:

Like Loading...