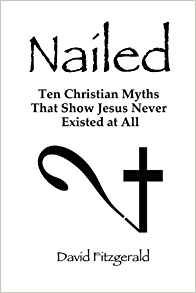

David Fitzgerald‘s essay, Ten Beautiful Lies About Jesus, that received an Honorable Mention in the 2010 Mythicist Prize contest has been expanded into a book, Nailed: Ten Christian Myths That Showed Jesus Never Existed At All. The book is clearly a hit:

David Fitzgerald‘s essay, Ten Beautiful Lies About Jesus, that received an Honorable Mention in the 2010 Mythicist Prize contest has been expanded into a book, Nailed: Ten Christian Myths That Showed Jesus Never Existed At All. The book is clearly a hit:

Nailed continues to garner more fans and accolades, and generate cranky hate mail. I was especially proud to see Nailed voted one of the top 5 Atheist/Agnostic Books of 2010 in this year’s AboutAtheism.com Reader’s Choice Awards! It’s a real thrill to have my book honored alongside world-class authors like the late, great Christopher Hitchens, Stephen Hawkins and all the contributors of John Loftus’ awesome, paradigm-wrecking collection The Christian Delusion. (From DF’s blog)

I’m especially pleased that David has given me permission to post a large chunk of his recent blogpost here. I began a couple of times to address Tim O’Neill’s ‘review’ of Nailed but never got beyond his first few points — Tim was so far from relating to anything that is actually written in the book that I could see it would take more time than it was worth to point it all out. (Perhaps we can coin a word for these sorts of anti-mythicist non-reviews; someone has suggested Grathneilians — though David happily reports he got along well with Dr McGrath, so that’s good.) So I usually ended up just posting two links: one to the first part of Tim’s review and the other to the relevant portion of Nailed online so anyone could read for themselves how off the planet Tim’s remarks were.

(There is another review of the bookhere.)

So I’m especially pleased David himself has taken the time to respond. Check it out on his blog where there are other comments. Since I know many hate following links I’ve sought permission to post it here, too:

And Then There’s This Guy…

That said, there is one review that I do want to respond to here; not simply because it’s almost completely wrong, but because it’s often so ass-backwards wrong in ways that actually prove the points I argue. (and because demonstrating all this gives a surprisingly high entertainment value) It’s the screed-in-book review’s clothing from an Australian blogger, Tim O’Neill. O’Neill calls himself a “wry, dry, rather sarcastic, eccentric, silly, rather arrogant Irish-Australian atheist bastard,” so you would think we would get along like a house on fire. Sadly, no. As George Bernard Shaw pointed out long ago, if you roast an Irishman on the spit, you can always get another Irishman to turn the crank… Continue reading “David Fitzgerald responds to Tim O’Neill’s review of Nailed”