Without citing any instances to support his claim, Bart Ehrman charged “mythicists” as sometimes guilty of dishonestly quote-mining Albert Schweitzer to make it sound as if Schweitzer supported the view that Jesus was not a historical person. Ehrman’s unsubstantiated allegation has been repeated by Cornelis Hoogerwerf on his blog (without any acknowledgement to Ehrman); Jona Lendering of Livius.org has reportedly alerted Jim West of Cornelis’s “observation” and Jim has in turn informed his readership of Cornelis’s “excellent post”.

The tone in which the debate about the existence or non-existence of Jesus has been conducted does little credit to the culture of the twentieth century. (Albert Schweiter, p.394, the

2001 Fortress edition of Quest) — and ditto for the 21st century!

Here’s an excellent post . . . on the way the Jesus mythicists misrepresent Schweitzer to further their unhinged, maniacal, idiotic goals. (From The Crazy ‘Jesus Mythicists’ Lie About Schweitzer the Way Trump Lies About Everything) [Link (https://zwingliusredivivus.wordpress.com/2017/01/07/the-crazy-jesus-mythicists-lie-about-schweitzer-the-way-trump-lies-about-everything/) no longer active as of 24th July 2019, Neil Godfrey]

If anyone knows who has quoted Schweitzer to support a claim that Jesus did not exist please do inform me either by email or in a comment below. I am not suggesting that no-one has mischievously or ignorantly misquoted Schweitzer to suggest he had doubts about the historicity of Jesus but I have yet to see who these mythicists are of whom Ehrman, Hoogerwerf and West speak. I do know that my own blog post quotations of Schweitzer have been picked up by others and recycled but I was always careful to point out that Schweitzer was no mythicist, and indeed that was a key reason I presented the quotations: the strength of their contribution to my own point was that they derived from someone who argued at length against the Christ Myth theory.

So I would like to know the identities of the “quack historians” of whom Cornelis Hoogerwerf writes:

To no surprise for those who are a little bit familiar with the contrivances of quack historians, Albert Schweitzer is getting quote mined to bolster the claims of the defenders of an “undurchführbare Hypothese” (infeasable hypothesis), as Schweitzer himself called the hypothesis of the non-existence of Jesus (p. 564). Part of it is due to the English translation, but another part is certainly due to the fact that quotations of his work circulate without context, and moreover due to the lack of understanding of Schweitzer’s time and his place in the history of scholarship. Perhaps some light from the Netherlands, in between the German and the Anglo-Saxon world, could help to clarify the matter.

There is nothing more negative than the result of the critical study of the Life of Jesus.

The Jesus of Nazareth who came forward publicly as the Messiah, who preached the ethic of the Kingdom of God, who founded the Kingdom of Heaven upon earth, and died to give His work its final consecration, never had any existence.

. . . .

Now, without context, it seems that Albert Schweitzer rejects the whole project of historical Jesus research. But nothing is further from the truth, for Schweitzer criticises the liberal scholarship that was current in the nineteenth century, which, according to Schweitzer, tried to make the historical Jesus a stooge for their modern religious predilections. That Jesus had never any existence. Schweitzer’s own historical Jesus was the eschatological Jesus, who remained strange, even offensive, to our time.

(Misquoting Albert Schweitzer, my bolding in all quotations)

What is the source of this claim? Has Cornelis Hoogerwerf really read any post, article or book in which Schweitzer has been so quoted for such a dishonest purpose? He cites none. But his wording does have remarkable similarities to the text of Bart Ehrman in Did Jesus Exist? when he made the same charge — also without citation of supporting sources.

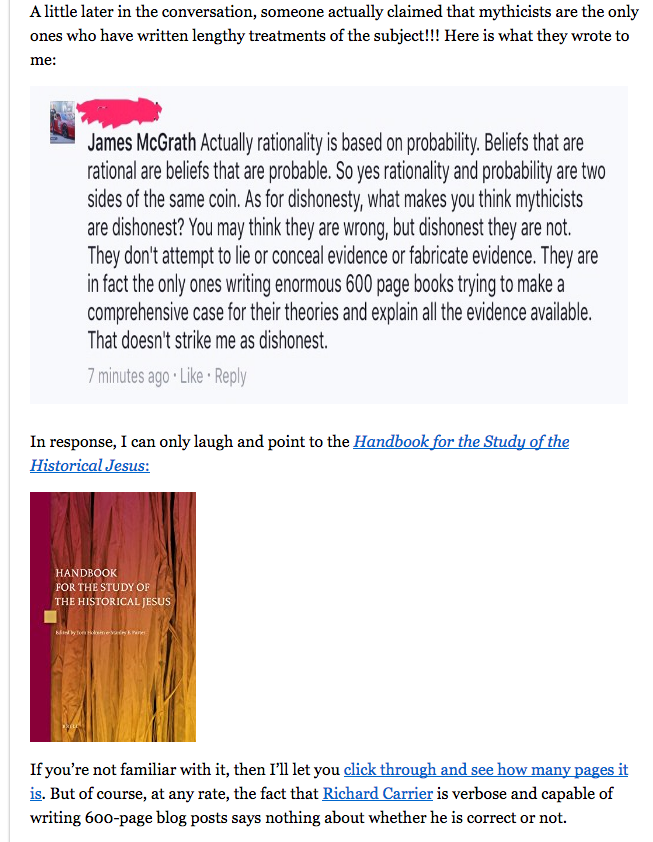

To lend some scholarly cachet to their view, mythicists sometimes quote a passage from one of the greatest works devoted to the study of the historical Jesus in modern times, the justly famous Quest of the Historical Jesus, written by New Testament scholar, theologian, philosopher, concert organist, physician, humanitarian, and Nobel Peace Prize-winning Albert Schweitzer:

There is nothing more negative than the result of the critical study of the life of Jesus.

The Jesus of Nazareth who came forward publicly as the Messiah, who preached the ethic of the Kingdom of God, who founded the Kingdom of heaven upon earth, and died to give his work its final consecration, never had any existence.

. . . .

Taken out of context, these words may seem to indicate that the great Schweitzer himself did not subscribe to the existence of the historical Jesus. But nothing could be further from the truth. The myth for Schweitzer was the liberal view of Jesus so prominent in his own day, as represented in the sundry books that he incisively summarized and wittily discredited in The Quest. Schweitzer himself knew full well that Jesus actually existed; in his second edition he wrote a devastating critique of the mythicists of his own time, and toward the end of his book he showed who Jesus really was, in his own considered judgment. For Schweitzer, Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet who anticipated the imminent end of history as we know it. (Did Jesus Exist? p. f)

I hesitate to suggest that Ehrman’s accusations were made without substance but I have yet to find any “mythicists” quoting the above passage by Schweitzer for the intent that Ehrman and Hoogerwerf claim. Is this an entirely manufactured accusation? Is West alerting readers to Hoogerwerf’s “excellent” relaying of a baseless rumour?

***

Cornelis Hoogerwerf adds a second part to his post: Continue reading “Albert Schweitzer on the Christ Myth Debate”

Like this:

Like Loading...

The Bible’s ethics are not for our time. They represent an age when policies like those of Trump’s “extreme vetting if immigrants” were whitewashed as inspirationally loving.

The Bible’s ethics are not for our time. They represent an age when policies like those of Trump’s “extreme vetting if immigrants” were whitewashed as inspirationally loving.