Continuing the series the evolution of the offering of Isaac into a Jesus story; earlier posts here.

Levenson argues that much of the early christology derives from a midrashic combination of verses associated with

- Isaac, the beloved son of Abraham,

- the suffering servant in Isaiah who went, like Isaac, willingly to his slaughter,

- another miraculous son, the son of David, the future messianic king laden with hopes of restoring the nation and establishing justice and peace throughout the world.

As outlined in my earlier post, Levenson shows that the “Beloved Son / Only Begotten Son” label can at times be used as a technical term for a son who is destined to be sacrificed or in some way given up to death or slavery by his father. Christians attributed this status to Jesus in relation to the twin themes of humiliation and exaltation.

While I am essentially here outlining notes from Levenson’s The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son, I cannot claim that I am accurately reflecting the nuances of Levenson’s thought. It is inevitable that my personal interest will govern the subtext and organization of these notes. (Although I do clearly make notes where I depart from Levenson with other material altogether.)

The THEME of HUMILIATION and DEATH

The Beloved Son

So when Jesus is declared by his heavenly Father to be “my beloved son with whom I am delighted” (as one reads in Mark 1:11 and 9:7, Matthew 3:17 and 17:5, Luke 3:2 and 9:35 and 2 Peter 1:17 and compares with John 3:16), an audience familiar with the story of Isaac and its Jewish interpretations from the second Temple period would hear God identifying Jesus with Isaac.

An earlier heavenly voice similarly had bestowed the same honour on Isaac: “Take your beloved son, the one you love, and offer him up as a burnt sacrifice” (Genesis 22:2). This narrative of the binding of Isaac (the aqedah) took on evolving importance in the Second Temple period, as discussed in previous posts (see my Levenson tag). Isaac came to be seen as a willing participant in his sacrifice that took on atoning significance for the sins of Israel. Isaac’s “sacrifice” even came to be recalled as a meaning of the Passover lamb.

With this background, as Levenson notes, “it is reasonable to suspect that the early audiences of the synoptic Gospels connected the belovedness of Jesus with his Passion and crucifixion” (p.200).

The Suffering Servant

The “beloved son in whom I delight” in Mark and the other New Testament passages cited above owed as much to the figure of the Suffering Servant in Isaiah:

This is My servant, whom I uphold,

My chosen one, in whom I delight.

I have put My spirit upon him,

He shall teach the true way to the nations. (Isaiah 42:1)

Isaiah 52:13-53:12 further depicts the servant of YHWH as “an innocent, humble, and submissive man who was, nonetheless, persecuted, perhaps even unto death. These persecutions were not meaningless, however: they served a redemptive role, for through them the servant atoned vicariously for those who maltreated him. . . . The identification of Jesus with the suffering servant of the Book of Isaiah . . . became a mainstay of Christian exegesis” (p.201).

Levenson observes that the Christian interpretation of this passage was not broken within their ranks until the twelfth century when Andrew of St. Victor interpreted the suffering servant as referring to the sufferings of the Jewish people during their Babylonian exile. This view led to him being accused of “judaizing” the Bible.

The suffering servant was also imagined as a sheep about to be slaughtered:

He was oppressed and He was afflicted,

Yet He did not open His mouth;

Like a lamb that is led to slaughter,

And like a sheep that is silent before its shearers,

So He did not open His mouth. (Isaiah 53:7)

Isaac Bound and the Suffering Servant

We don’t know whether the Christian community was the first to relate the aqedah and suffering servant images to each other, of if the Christians were drawing on earlier Jewish exegesis. “Either way, the equation of Isaac with the suffering servant has its own potent midrashic logic” (p.201):

Sacrificial lambs

The binding of Isaac was seen as prefiguring the Passover lamb; the suffering servant was compared with a lamb to be slaughtered

Willingly accept their fate

Isaac came to be seen as willingly accepting his fate; the suffering servant also willingly accepts his fate

Their deaths give God complete pleasure

Both Isaac and the suffering servant provide their heavenly father with complete pleasure when faced with death (c.f. Isaiah 53:10-11)

The meaning of the chosen and beloved status

The chosen and beloved status of both Isaac and Jesus meant that each was fated to humiliation and exaltation, death and glory

Their deaths are redemptive

The blood of Isaac was seen in place of that of Israel and so saved Israel; the stripes of the suffering servant healed many, his soul was made an offering for sin

The THEME OF AUTHORITY and EXALTATION

Beloved Son and the story of Joseph

At the transfiguration of Jesus where select disciples and the chosen readers glimpse the glory of Jesus to come, they hear him designated the Beloved Son, and are reminded again of his lot to be humiliated and sacrificed. But they hear something else in addition. He has authority. He is the one to be listened to and obeyed:

Then a cloud came, casting a shadow over them; then from the cloud came a voice, “This is my beloved son. Listen to him.” (Mark 9:7; c.f. Matthew 17:5 and Luke 9:35)

The beloved son to be sacrificed is to receive the homage of others.

This has less to do with Isaac or the suffering servant than it does with the Joseph story in Genesis 37-50.

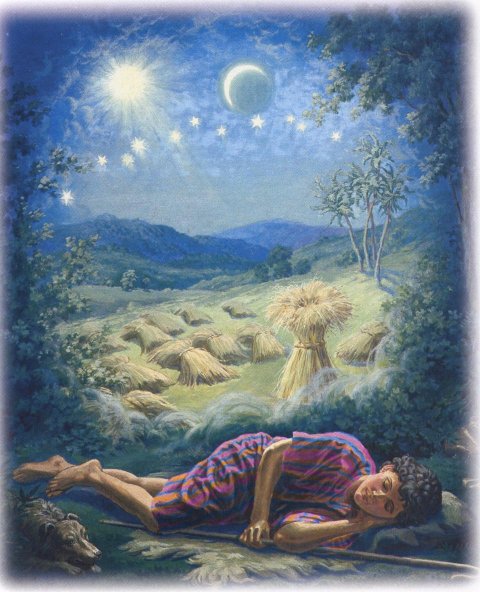

The starting point must be the fact that Joseph was singled out as the most beloved son of his father. He was the son of his old age and from his favoured wife. (Genesis 27:3).

Levenson has earlier discussed this narrative in depth. In sum, it is in part a story of how its hero came to be catapulted into the status of privilege and authority as had been promised him as a child, and how before this promise was granted he had to suffer many symbolic deaths (the first which his father took to be a real death). His final status of authority meant that even his older brothers had to listen to him and obey.

Transfiguration as an analog of the Joseph report to his father and brothers

In both the narrator depicts a future grandeur that seems completely out of place at the moment

Before the realization of this glory, both beloved sons must confront death, and experience betrayal and abandonment, apparently never to be seen again.

The contributions of the Joseph story to the Gospels

“What the Joseph story more than any other tales of the beloved son contributes to the Gospels is the theme of disbelief, resentment, and murderous hostility of the family of the one mysteriously chosen to rule” (p.202)

In the gospels the betrayal is principally by Judas who takes 30 pieces of silver in exchange for Jesus. Levenson remarks that it would seem more than possible that this episode was drawn from the sale of Joseph, as proposed by Judah (the namesake of Judas), for 20 pieces of silver.

The amount or 20 pieces of silver appears to be based on the price for a male Joseph’s age in Leviticus 27:5. The Gospel amount of 30 pieces may come from Zechariah 11:12

The same passage in Zechariah speaks of the shepherd breaking his staff, named Unity, to demonstrate the annulling of the brotherhood between Judah and Joseph. In the Joseph story Judah is the most important of Joseph’s brothers, and is the one who seeks to heal the rift in the family. (Another passage, Ezekiel 37:15-28, also speaks of 2 sticks, representing Judah and Joseph, and wants them reunited.)

Levenson comments: “In light of these biblical precedents, it was not an unlikely move for the Gospels to associate the fatal rift among the twelve disciples with the betrayal of Joseph, their father’s beloved son and the one among the twelve destined to rule despite his brothers’ enmity and perfidy.” I would suggest, rather, that the original account of the betrayal of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark does not depict such a rift among the twelve disciples as Levenson seems to assume. It was well been argued that Mark’s gospel depicts all Twelve in some way betraying Jesus: Judas directly, Peter by denying him, all by abandoning him. They may be seen as just as collectively responsible for the betrayal of Jesus as all of Joseph’s brother are for his betrayal.

Beloved Son and the Messianic King

“The theme of authority [the command to “Hear Him!” at the transfiguration] draws the traditions of the beloved son into relationship with another important stream in Jewish tradition, that of messianism” (p.203).

Again, the messianic oracles resonate with the same terms of identity given by God to Jesus:

You are my son, today I have begotten you

(It is going beyond Levenson’s comments, but early Christians such as Justin testify to this same expression being used of Jesus.)

Royal theology of the House of David

The literature spoke of a divine commission to the Davidic king of heir, even if the latter were newborn or unborn. This literature calls for submission to the new king at a time when his rule seemed shaky:

The kings of the earth take their stand

And the rulers take counsel together

Against the LORD and against His Anointed/Messiah (Psalm 2:2)

God responds by mocking the plotters and establishing his anointed king:

“But as for Me, I have installed My King

Upon Zion, My holy mountain.” (Psalm 2:6)

The king then speaks, reciting the terms of his commission from God:

“I will surely tell of the decree of the LORD:

He said to Me, ‘You are My Son,

Today I have begotten You.

‘Ask of Me, and I will surely give the nations as Your inheritance,

And the very ends of the earth as Your possession.

‘You shall break them with a rod of iron,

You shall shatter them like earthenware.’ ” (Psalm 2:7-9)

The king rules as Son of Yahweh.

This may be nothing more than a literary metaphor, since treaties establishing suzerainty and vassalage likewise used the terms “father” and “son” as diplomatic conventions to indicate that status.

Or it could be more than a convention of language. It could be “a living metaphor” in which the King hears the voice from heaven that gives him his authority to rule as God’s Son on earth. The Davidic King could be the manifestation of the universal rule of God on earth. The command is to Hear Him, or face the severest consequences.

Some of the messianic literature with its emphasis on the birth of the Davidic king appears to confirm this latter interpretation. The king is not an ordinary person who is a metaphoric son of God according to the diplomatic jargon of the covenant, but is a miraculous figure, and his accession transforms the world by ushering in a new age of the justice of God. Once enthroned he really was the divine son.

For unto us a child is born,

unto us a son is given:

and the authority shall be upon his shoulders:

He has been named

“The Mighty God is planning grace;

The Eternal Father, a peaceable ruler” —

In token of abundant authority

and of peace without limit

upon the throne of David, and upon his kingdom,

That it might be firmly established

In justice and equity

Now and evermore. (Isaiah 9:6-7)

The above points to the miraculous birth of the Davidic King, and this functions as yet another link with the Beloved Son . . . .

Beloved Son and Miraculous Birth

So if the birth of the king (regardless of the chronological age of the king at the time this was declared) was a miraculous event, we have another link with the tradition of the Beloved Son in the Genesis narratives. For in those stories are all born of a miracle, as a direct result of divine intervention. In the cases of Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, they were all born of barren women, in one case even of a woman who was well beyond child-bearing years at the time — Sarah, Rebekah and Rachel.

It is a very common trope for heroic figures to be born outside the course of nature. (e.g. Samson in Judges 13; Samuel in 1 Samuel 1)

“One function of these stories is to legitimate the special status of the person to whom miraculous birth is attributed. His authority is not something that he has usurped: a gracious providence has endowed him with it, thus to the benefit of the entire nation” (p.205). Hence:

For unto us a child is born,

unto us a son is given

Isaac’s priority lineage ahead of his older brother, Ishmael, and Isaac’s priority ahead of his older brother Esau, and the younger brother Joseph’s right to supremacy, were all legitimated by the miraculous circumstances of their births. They were bestowed authority, against all natural expectation and concourse, by the authoritative grace of God.

The New Testament equivalent of the beloved son being born to a barren woman is the birth of Jesus to a virgin.

In the Gospel of Matthew the virgin birth derives from a midrashic link to the Septuagint (Greek) text of Isaiah 7:14, where a Greek word often meaning virgin is used of the mother of the son to be named Immanuel (God with us) is to be born.

In the Gospel of Luke the virgin birth is associated much more directly with the titles of the one to be born “Son of the Most High” and “Son of God” – and with Jesus’ claims upon the Davidic throne (Luke 1:32-35).

The Gospel of Luke therefore draws on a very literal understanding of “son of God” in the Judean royal theology described in the previous section.

BELOVED SON + SON OF GOD = GOSPEL DRAMA

Levenson, p. 206:

Within the overall structure of the Gospels, however, the two vocabularies of sonship, that of the beloved son and that of the Davidic king as the son of God, reinforce each other powerfully. They yield a story in which the rejection, suffering, and death of the putatively Davidic figure is made to confirm rather than contradict his status as God’s only begotten son.

PASSOVER + BELOVED SON + FIRST BORN = JESUS

All four canonical gospels link Jesus’ death with the Passover. The synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) coincide the Last Supper with the Passover meal. Thus when Jesus declares the bread and wine to be his flesh and blood (or emblematic of them) these have to be judged as having a paschal significance.

The Gospel of John has the distinction of placing Jesus’ death itself on the Passover, so the Last Supper the evening before took place without any paschal associations. (Contrary to Levenson, however, I would note that the author of this gospel does associate bread and wine with Jesus’ paschal body – only at his implicit commentary on the feeding of the 5000 (John 6) — not on the Passover eve.)

The Gospel of John

So the author of GJohn links the body of Jesus on the cross, not the meal eaten the evening before, with the Passover. Thus in John 19:31-37 we see a gospel author relating the crucified body of Jesus

- to Numbers 9:12 (not a bone was to be broken in the Passover meal)

- and to Zechariah 12:10 (they will look upon him whom they pierced)

In the case of the latter reference to Zechariah 12:10, Levenson notes: “Here it is useful to remember that the relevance of a verse often extends beyond the words that the midrashist cites. In the case of Zech 12:10, it is highly suggestive to note that the words that follow those cited in John 19:37:

. . . wailing over them as over a favorite son and showing bitter grief as over a first-born. (Zech. 12:10c)

In the Septuagint (Greek) “Old Testament”, the word for “favorite son” is rendered, in the Greek, agapetos, “beloved one”. This is the same word the Septuagint used to translate the Hebrew “favorite son” (yahid) in the story of the binding of Isaac, the aqedah, in Genesis 22:2, 12, 16. (See fuller discussion in previous post.)

It thus appears that the author of GJohn is equating the first-born and beloved son with the paschal lamb, and all three of these with Jesus.

The Baptism of Jesus scene in the Gospel of John is not really a baptism of Jesus. Rather, it is a proclamation of the Baptist about the identity of Jesus — with no baptism. John declares Jesus to be the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world (John 1:29).

Strictly the Passover lamb was not a sin offering. Levenson replies to this: “We must not assume that the fine technicalities of sacrificial classification weighed heavily upon the minds of the evangelists as they drew upon biblical materials for their own purposes. More importantly, the unclassifiable passover sacrifice of Exodus 12 does indeed have much in common with the sin offering, for it is through the blood of the lamb that lethal calamity is deflected, as the mysterious Destroyer is prevented from working his dark designs upon the Israelite first-born . . . ” ( p. 208 )

So the author of GJohn does not repeat the Synoptic words, “You are my beloved son, with you I am well pleased.”

But he did equate the beloved son with the paschal lamb.

And he has John the Baptist equate the Lamb of God with the Son of God (John 1:34).

The equation of the Son of God with the Lamb of God takes us back to Exodus 34:20 where the lamb was destined as a substitute for the firstborn to be sacrificed. Previous posts in this Levenson series have demonstrated the identification of the binding of Isaac (Genesis 22:13) with the narrative of the Exodus from Egypt (Exodus 13:11-15).

Revelation 12:10-11 also points to an early Christian understanding that the blood of the lamb overpowers the “accuser”, or Satan, and enables Christ to come to power. Levenson notes that this accuser in Revelation has “a striking analogue” in Jubilees 17:15-16, previously discussed for its relationship to the Exodus Destroyer and the Passover.

Thus John’s Gospel can be seen as both opening (1:29) and closing (19:36) with Jesus as the Lamb of God, the Paschal Lamb, and both of these brackets are taken from the story of the Passover — “the story of how the preternatural forces of death were foiled and the doomed first-born miraculously allowed to live” (p. 209).

Next to look at Paul’s contribution to this, and its significance for the self-identity of the church and relations with Jews.

Like this:

Like Loading...