If you are like me and a little mystified about how we got to where we are today with increasing numbers actually deploring our traditional democratic systems, with more or our fellow citizens seemingly ignorant of how our system of government works, even of how society functions, and are just a wee bit concerned about where we are headed, you might find some clarifying explanation in Degenerations of Democracy by Craig Calhoun, Dilip Parameshwar Gaokar and Charles Taylor.

If you are like me and a little mystified about how we got to where we are today with increasing numbers actually deploring our traditional democratic systems, with more or our fellow citizens seemingly ignorant of how our system of government works, even of how society functions, and are just a wee bit concerned about where we are headed, you might find some clarifying explanation in Degenerations of Democracy by Craig Calhoun, Dilip Parameshwar Gaokar and Charles Taylor.

How did we get from the great hopes of the 1960s to here? Australian history, pre-World War I especially, was a dramatic social pioneering scene partly by the way obstacles were overcome. But I think future hopes held on and were reinvigorated with a new boost in the 60s and early 70s. But today I read the views of the elderly and of historians who say that today we face a social cynicism that was not even paralleled in the 1930s. I would like to think the new Australian government is doing something to restore a little hope with its consensus approach, but if so, it’s not going to change social attitudes overnight nor by itself. And we are just one corner of the world anyway.

I’ve begun reading Degenerations of Democracy (Introduction, Chapter 1 and part of the final “What is to be done” chapter) and it makes a lot of sense.

In chapter one Charles Taylor traces how and why there has been a decline in our (“us citizens'”) sense of power to change things by working or acting together to influence governments. The rot set in from the mid 1970s.

But that is only the first part of what has gone wrong. What stems from that sense of powerlessness, at least among large sectors of the population, is the age-old tendency to seek scape-goats, to identify those who need to be excluded because they are “not really part of us”. The immigrants, the indigenous populations, the elites. (Certain elites do share a good part of the blame, of course, especially those who own the media and those who run the global enterprises. But what is needed here is not the sending of those elites to the guillotine but a restructuring of “the system” and redistributing the wealth.) The point is, the sense of community is breaking down, or at least being redefined to exclude certain groups. That’s breaking up the very foundation on which a democracy survives. I liked Taylor’s explanation of the difference between Bernie Sanders’ populism and Donald Trump populism:

Now, a word about the term “populism.” There is more than one kind, with different political implications. Even in the 2016 election in the United States, the word was used to apply to two movements, represented by Bernie Sanders and by Donald Trump, respectively. One obvious meaning of the term applies when the “people,” in the sense of the demos or nonelites, are mobilized to erupt into a system that has been run without considering them; they are breaking down the walls, breaking down the doors, disturbing business as usual, demanding redress of grievance. But there is a very big difference between the Bernie and the Donald version: the Bernie version is truly inclusive; it’s not excluding anyone. One may not agree with the particular policies put forward; one may or may not be happy about this populist eruption. But Bernie Sanders’s program does not embrace the notion that precedence gives some citizens greater rights than others. This exclusionary feature is basic and, I think, absolutely fatal to the populist appeals of Donald Trump, Marine Le Pen, and Geert Wilders. It is both deeply divisive and in programmatic terms a dead-end.

Excerpt From: Craig Calhoun. “Degenerations of Democracy.” Apple Books.

And from the “decline of citizen efficacy” through “waves of exclusion” we arrive at the final killer: polarization. When we insist on democracy meaning “the rule of a majority” without any care for the community as a whole we run into a serious and dire situation. When “majorities” take on definitions that exclude any interest in the welfare of others; when members of self-defined “majorities” say “you” would join them too when you “wake up” and “see” what they see; and when “majorities” insist that they have a need to rule in perpetuity in order to safeguard “civilization”, “white culture”, . . . being blind to the fact that in a large society the needs of different groups change and realignments and new priorities are always going to be part of a democracy’s life.

It’s a long read. I’ll be dabbling in it on and off over some time. But I’ve already been thinking a lot about what I have read so far and trying to see if I can make better sense of what has happened “to us” and why the world has not turned out the way we had expected some decades ago. I’ve already jumped to the “What Is To Be Done” chapter at the end.

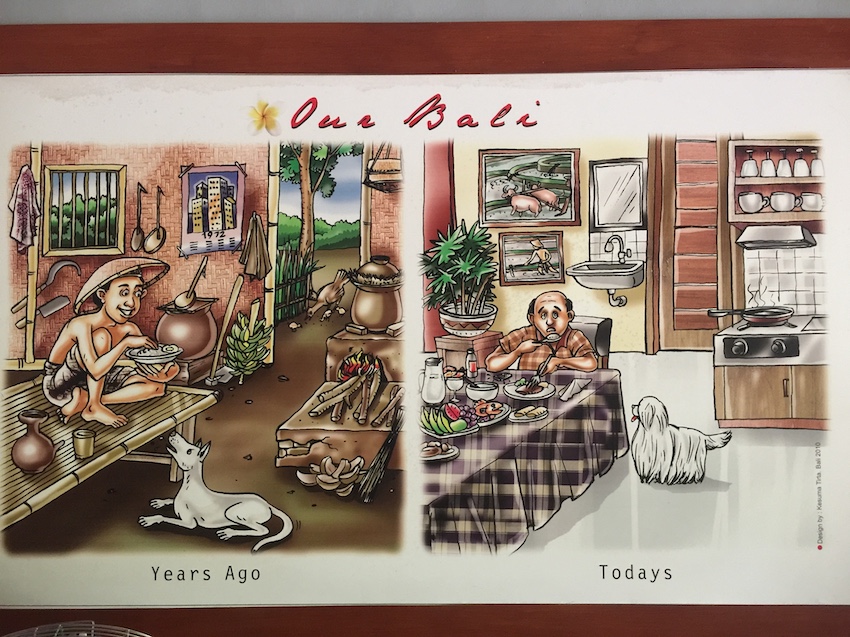

If that’s “Paradise”, I believe Jan Steen from 1670 captured the happiest scene in the exhibition:

If that’s “Paradise”, I believe Jan Steen from 1670 captured the happiest scene in the exhibition: