Richard Sakwa, Professor of Russian and European Politics at the University of Kent, scares me. He compares in Frontline Ukraine the current international tensions over Ukraine with those over the Balkans prior to World War 1. He further compares the dynamics between NATO/”Wider Europe” and Russia with those between Western Europe/UK and Germany prior to World War 2.

On the one hundredth anniversary of World War I and the seventy-fifth anniversary of the start of World War II, and 25 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Europe once again finds itself the cockpit of a great-power confrontation. How could Europe have allowed itself to end up in this position, after so many promises of ‘never again’? This is the worst imbroglio in Europe since the 1930s, with pompous dummies parroting glib phrases and the media in full war cry. Those calling for restraint, consideration and dialogue have not only been ignored but also abused, and calls for sanity have not only been marginalised but also delegitimated. It is as if the world has learned nothing from Europe’s terrible twentieth century. (Sakwa, R. 2015, Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands, I.B. Taurus, London. p. 1, bolding mine in all quotations)

Sakwa continues:

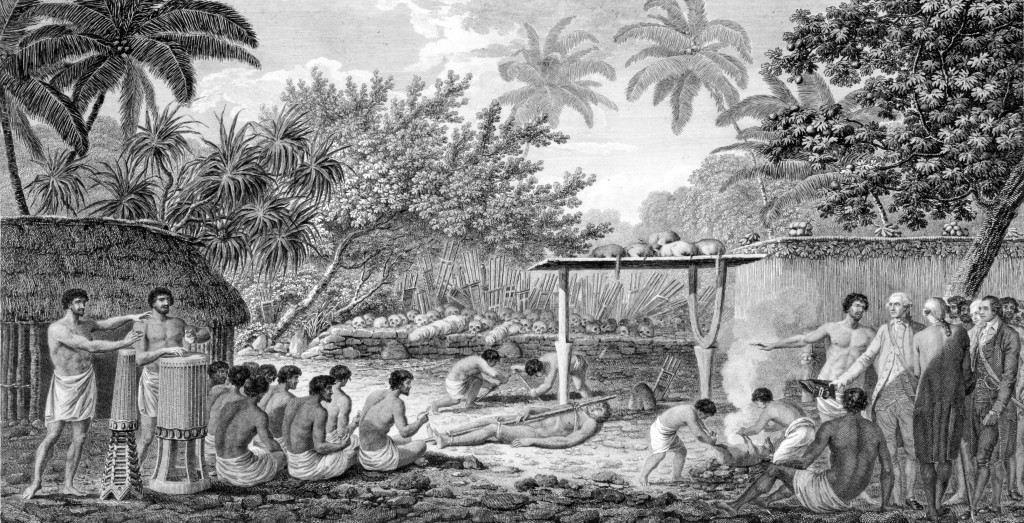

The slew of books published to commemorate the start of the Great War reveals the uncanny similarities with the situation today. The war cost at least 40 million lives and broke the back of the continent, yet in certain respects was entirely unnecessary and could have been avoided with wiser leadership. If key decision makers had not become prisoners of the mental constructs that they themselves had allowed to be created, and if the warning signs in the structure of international politics had been acted on, then the catastrophe could have been averted. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914 could well have remained a localised incident if Europe had not already been poised for conflict. (p. 1)

Those are disturbing words.

Europe in 2014 has once again become the crucible of international conflict, harking back to an era that has so often been declared to be over. Today, Ukraine acts as the Balkans did in 1914, with numerous intersecting domestic conflicts that are amplified and internationalised as external actors exacerbate the country’s internal divisions. (p. 3)

So far I have only read the first two chapters but I read them while the news was hailing as historic the rise and rise of Hillary Clinton towards the White House. And that makes the insights and warnings of Sakwa’s book even more scary. Sakwa documents Hillary Clinton’s attitude towards Russia as epitomizing the worst of the blindly destructive and culpably foolish that beset the leaders who stumbled into war in 1914.

I found Sakwa’s description of Ukraine, both historical and contemporary, most enlightening. I had not grasped just how deep-seated are the roots of the divisions in Ukraine that we are now witnessing, or how ancient is some of the puerile and fascist sounding anti-Russian talk coming out of Ukraine’s leaders today. Nor had I realized how equally ancient are the voices of pluralism seeking partnership with Russian and other Slav peoples.

Most depressing is the way the EU has tied itself to advancing the very divisions and conflicts in Europe that it was originally founded to obliterate. There is a pattern expressed in the books I have been reading. Afshon Ostovar in Vanguard of the Imam shows how the Iranians in response to 9/11 were offering much practical information and assistance to the United States to enable them to locate and capture the al Qaeda and Taliban targets they most wanted, but how the US rebuffed these efforts because they came from Iran. Sakwa shows the same pattern of Western rejection of anything coming from an increasingly demonised Russia.

In this context, here is some of what Sakwa tells us about Hillary Clinton’s views on Russia:

A very different approach was adopted by Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State in President Barack Obama’s first administration from 2009 to 2013. In her memoirs Hard Choices she stresses US global leadership and the country’s commitment to democracy and human rights, which is hardly surprising, but more disturbing is the harsh inability to understand the logic of Russian behaviour. As long ago as 2008, during her failed presidential bid, Clinton asserted that Putin, as a former KGB agent, ‘doesn’t have a soul’, to which Putin riposted that anyone seeking to be US president ‘at a minimum […] should have a head’. She interpreted actions in support of independent Russian political subjectivity as an aggressive challenge to American leadership, rather than the normal expression of great-power autonomy in what Russia considers a multipolar world of independent nation states. She takes a consistently hawkish view of the world, urging Obama to take stronger action in Afghanistan, Libya and Syria, but when it comes to Russia her views are particularly harsh and unenlightened. She considers Putin a throwback to a nineteenth-century world of zero-sum realpolitik, intent on rebuilding the Russian Empire through Eurasian integration. Through this prism, she interprets Russian actions in Georgia in 2008 and in Crimea in 2014 as part of an aggressive strategy, rather than as defensive reactions to perceived challenges.

. . . Her Cold War stance is reflected in her parting injunction to Obama that ‘the only language Putin would understand’ is ‘strength and resolve’. (p. 33)

Continue reading “Sleepwalking once again into war, this time nuclear”