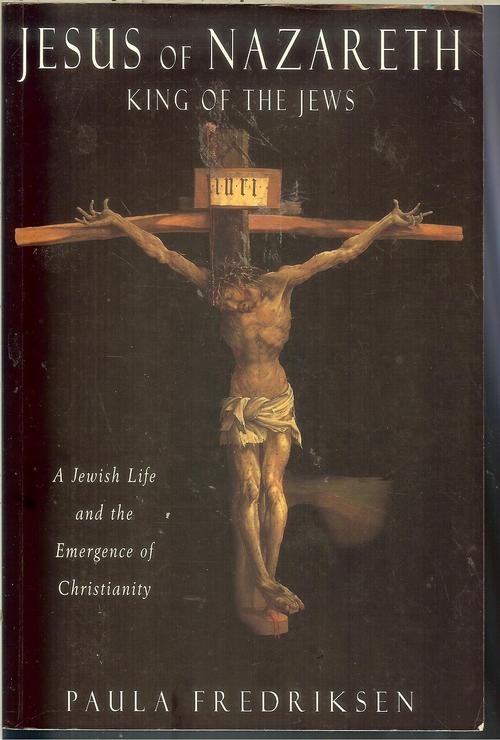

The title of this post is a lazy one. In fact, Paula Fredriksen is only one of many biblical historians who are guilty of this fallacy in their historical reconstructions of Jesus. I am merely using one detail from her book, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, to illustrate a basic methodological error that is so deeply ingrained in historical Jesus studies that I suspect some will have difficulty grasping what I am talking about.

The title of this post is a lazy one. In fact, Paula Fredriksen is only one of many biblical historians who are guilty of this fallacy in their historical reconstructions of Jesus. I am merely using one detail from her book, Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews, to illustrate a basic methodological error that is so deeply ingrained in historical Jesus studies that I suspect some will have difficulty grasping what I am talking about.

Fredriksen begins by declaring that historical Jesus studies begin with one indisputable “fact” – that Jesus was crucified by Pilate, and crucifixion was a punishment usually reserved for political insurrectionists. She then links this to a “second incontrovertible fact” (p.9), that Jesus’ followers, his disciples, were not executed.

Fredriksen sees her task as an historian to explain this paradox: why a leader would be executed as an insurrectionist threat, while his followers were ignored. Fredriksen also believes that one of the “trajectories” that must be explained in this context, is the fact that the same followers began the movement that became Christianity soon afterwards. There is more to Fredriksen’s argument, but I am highlighting these aspects of it for the purpose of demonstrating a basic methodological flaw that no historian should commit.

What Fredriksen has apparently overlooked before commencing her work is:

- the external evidence for the date her main sources, the canonical gospels, were extant

- the politico-religious matrix in which the canonical gospels made their earliest appearance

If the gospels were composed before the second century, it appears we are left with little reason to think that they found a receptive audience until well into the second century. Many scholars seem convinced that Justin Martyr knew of the canonical gospels and referred to them as Memoirs of the Apostles. For the sake of argument I am willing to accept this proposition. I acknowledge this belief has some excellent support in the evidence. Justin’s successor, Tatian, certainly knew of these gospels and composed a harmony of them.

But what should be of significance to any historian who is assessing the nature of their source documents, in this case the canonical gospels, is the intellectual environment in which they make their first appearance. We know Justin was a propagandist, like most of the other “Fathers” of his century, and that one of his keen interests was to justify his theological views, or the views of the Christianity he represented, by tracing its roots back to Jesus through the twelve apostles.

Genealogies were a political tool used to justify the pedigree of one’s own position, and to demonstrate the error of one’s opponents.

Justin proclaimed that the Christian movement or philosophy he represented was sound because it could be traced back to twelve apostles who were witnesses of Jesus’ mission, and his resurrection from the dead. (He apparently knows nothing of any Judas to confuse things, so whenever he speaks of the twelve, he indicates that the same ones who went out through the world preaching the gospel were the same as who were with Jesus during his mission on earth.)

These twelve disciples make their first appearance in the evidence as tools or foils to prove the truth of the Christian message being taught by Justin. They serve an ideological or narrative function.

And that is how the disciples appear in the canonical gospels, too. They serve as dramatic foils in the first part of the synoptic gospel narrative to make Jesus look all the more insightful and righteous beside their own ignorance and cowardice. They are always there to ask the right question, or perform the right act, to bring the right answer needed for the edification of the gospel reader.

They are also there to demonstrate or witness the “fact” of the resurrection. In John’s gospel, we can be excused for thinking that the original author of that gospel only thought of 7 disciples. The few bland and disconnected notes of their being twelve could be later redactions.

So from the very first times we see reference to the disciples of Jesus, they are always there to perfectly fulfill a dramatic, narrative or theological function.

Now it could well be that in real life, in real history, this is what the disciples did really do. And it could be a fact that the only details that survive about the disciples from this time just happen to be those that do serve these most functional purposes.

But then again, one has to wonder. Paula Fredriksen rejects the historicity of the Temple Action (“cleansing of the temple”) by Jesus, and part of her reason is that its details fit too neatly into the dramatic plot structure of the gospels.

Actual history rarely obliges narrative plotting so exactly: Perhaps the whole scene is Mark’s invention. (p. 210)

If all the details of the temple action fits the plot so perfectly, then I suggest the same can be said for all the details about the disciples we read in the synoptic gospels.

Fredriksen’s fallacy is not in accepting the disciples as historical, but in accepting them as historical persons without clearly addressing her rationales for doing so. And part of that rationale needs to address the fact that every detail we read about the disciples serves a narrative or theological function. Why not presume, therefore, that they have been created for these purposes?

Historians often reject the historicity of a particular detail in a narrative, such as a miracle, or a fulfilled prophecy, if they can see that its inclusion is tendentious for the sake of a particular doctrine or narrative function. Why not apply the same logic to the disciples themselves?

When one reads history or biographical details of Julius Caesar or Alexander the Great, one encounters many details and characters that do not necessarily fulfill any plot requirement or serve any political or propaganda interest. We have, therefore, plausible grounds for accepting the probability of the existence of these people. Of course, sometimes additional and seemingly incidental details are created by fiction writers to create an air of verisimilitude. But when we are dealing with writings about which we have corroborating primary evidence, we can feel confident we are in the realm of reading something more or less close to “real history”.

I wish I had time to illustrate the particular points I have made with direct quotations from Justin and the gospels to support the argument I have made. Unfortunately, time constraints just don’t allow that at the moment. So maybe this post can serve as an outline draft for a more complete one some time in the future. Meanwhile, reference to Justin’s statements about the disciples can be found at my vridar.info site.

Like this:

Like Loading...