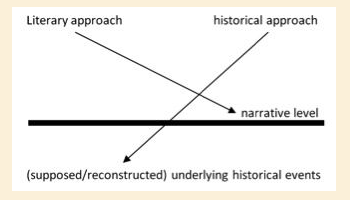

The following is not an argument in itself for Luke’s imitation of the utopian community in Plato’s Republic but it does provide the raw materials for such an argument. In another post I plan to elaborate on explanations for the points in common between the earliest Christians in Acts and Plato’s description of the guardians in his ideal state. Hint: they have to do with the relatively recent advances in studies of the way ancient authors imitated master-works and re-wrote them through a process we call “intertextuality”.

The table comes from “The Summaries of Acts 2, 4, and 5 and Plato’s Republic” by Rubén Dupertuis, a chapter in Ancient Fiction: The Matrix of Early Christian and Jewish Narrative. After the table I Dupertuis suggests that several inconsistencies in the Acts narrative may be explained most simply if the author was emulating the narrative of the ideal society led by Plato’s philosopher-kings. Traditional explanations for these inconsistencies have suggested the author was switching sources and/or not concerned about consistency. I’ll also cover these explanations in a future post.

First, have another look at those utopian summaries of the first Church. All quotations are from the 21st Century King James Version:

Acts 2:42-47

42 And they continued steadfastly in the apostles’ doctrine and fellowship, and in the breaking of bread and in prayers.

43 And fear came upon every soul, and many wonders and signs were done by the apostles.

44 And all who believed were together and had all things in common,

45 and they sold their possessions and goods and divided them among all men, as every man had need.

46 And continuing daily with one accord in the temple, and breaking bread from house to house, they ate their meat with gladness and singleness of heart,

47 praising God and having favor with all the people. And the Lord added to the church daily such as should be saved.

Acts 4:32-35

32 And the multitude of those who believed were of one heart and of one soul; neither said any one of them that any of the things which he possessed was his own, but they had all things in common.

33 And with great power the apostles gave witness to the resurrection of the Lord Jesus, and great grace was upon them all.

34 Neither was there any among them that lacked, for as many as were possessors of lands or houses sold them, and brought the prices of the things that were sold

35 and laid them down at the apostles’ feet. And distribution was made unto every man according as he had need.

Acts 5:12-16

12 And by the hands of the apostles were many signs and wonders wrought among the people, and they were all with one accord in Solomon’s Porch.

13 But of the rest, no man dared join himself to them, but the people magnified them.

14 And more believers were added to the Lord, multitudes both of men and women,

15 insomuch that they brought forth the sick into the streets and laid them on beds and couches, that at least the shadow of Peter passing by might overshadow some of them.

16 There came also a multitude out of the cities round about unto Jerusalem, bringing sick folks and those who were vexed with unclean spirits; and they were healed, every one.

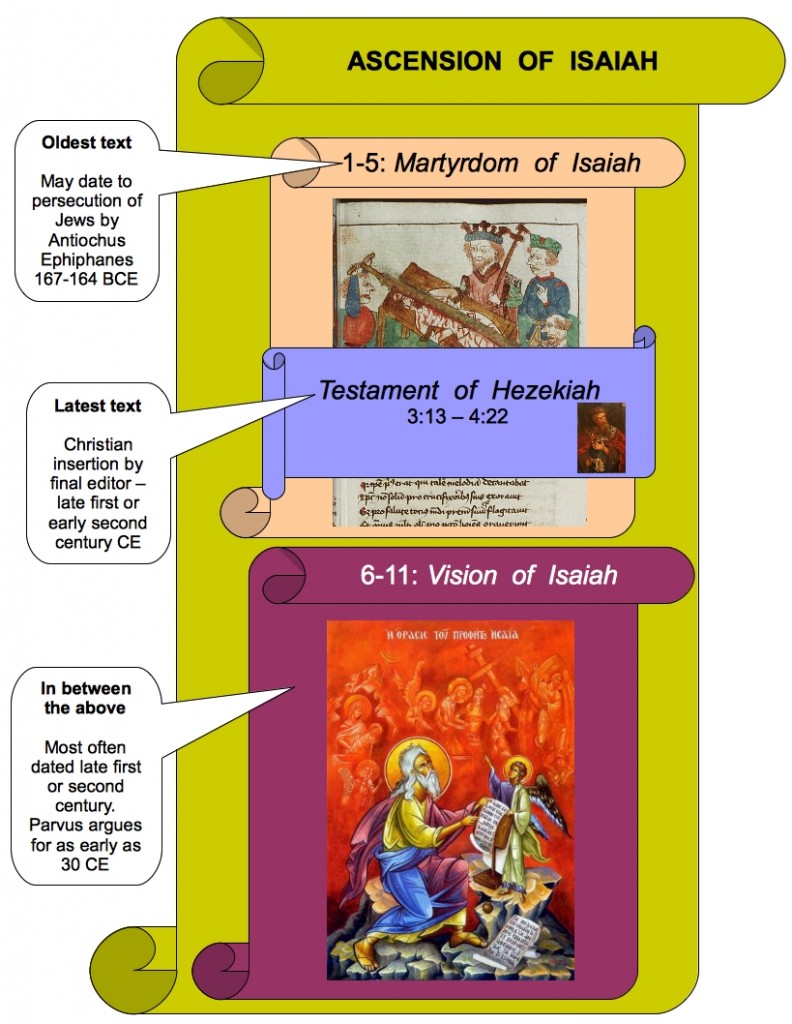

Dupertuis concludes his discussion on context, structure, terminology, density of parallels, with the following summary tables:

.

Support of the Guardians / Apostles

[table “” not found /]Continue reading “Earliest Christians fulfil Plato’s Utopia”