The latest contest started when James McGrath made a mockery of his understanding of Carrier’s mehod: Jesus Mythicism: Two Truths and a Lie

I have run the to and fro posts through a Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) analysis. Here are the interesting results:

| VARIABLE |

MCGRATH 1

Two Truths

(449 words) |

CARRIER

Wrong Again

(2485 words) |

MCGRATH 2

Mythicist Math

(680 words) |

Analytic thinking:

(the degree to which people use words that suggest formal, logical, and hierarchical thinking patterns) |

82.22% |

32.85% |

55.17% |

Authenticity:

(when people reveal themselves in an authentic or honest way) |

49.57% |

34.39% |

39.55% |

Clout:

(the relative social status, confidence, or leadership that people display through their writing) |

38.59% |

47.75% |

48.82% |

Tone:

(the higher the number, the more positive the tone) |

92.86% |

16.55% |

13.75% |

| Anger: |

0.22% |

0.56% |

0.88% |

.

Tone

Unfortunately when one reads McGrath’s Two Truths post one soon sees that his very positive tone (over 92% positive) is in fact an indication of overconfidence with the straw-man take-down.

But but but….. Please, Richard, please, please, please! Don’t fall into McGrath’s trap. Sure he sets up a straw man and says all sorts of fallacious things but he also surely loves it when he riles you. It puts him on the moral high ground (at least with respect to appearances, and in the real world, despite all our wishes it were otherwise, appearances do seriously count).

But see how McGrath then followed with a lower tone — and that’s how it so easily can go in any debate on mythicism with a scholar who has more than an academic interest in the question.

Anger

Ditto for anger.

This variable was measured by the following words:

| MCGRATH1 |

CARRIER |

MCGRATH2 |

| lying |

destroyed

argued

argument

liar

arguments

argues

lied

lies

damned |

insults

criticized

argument |

Clearly a more thorough and serious analysis would need to sort words like “argument” between their hostile and academic uses.

Analytic thinking style

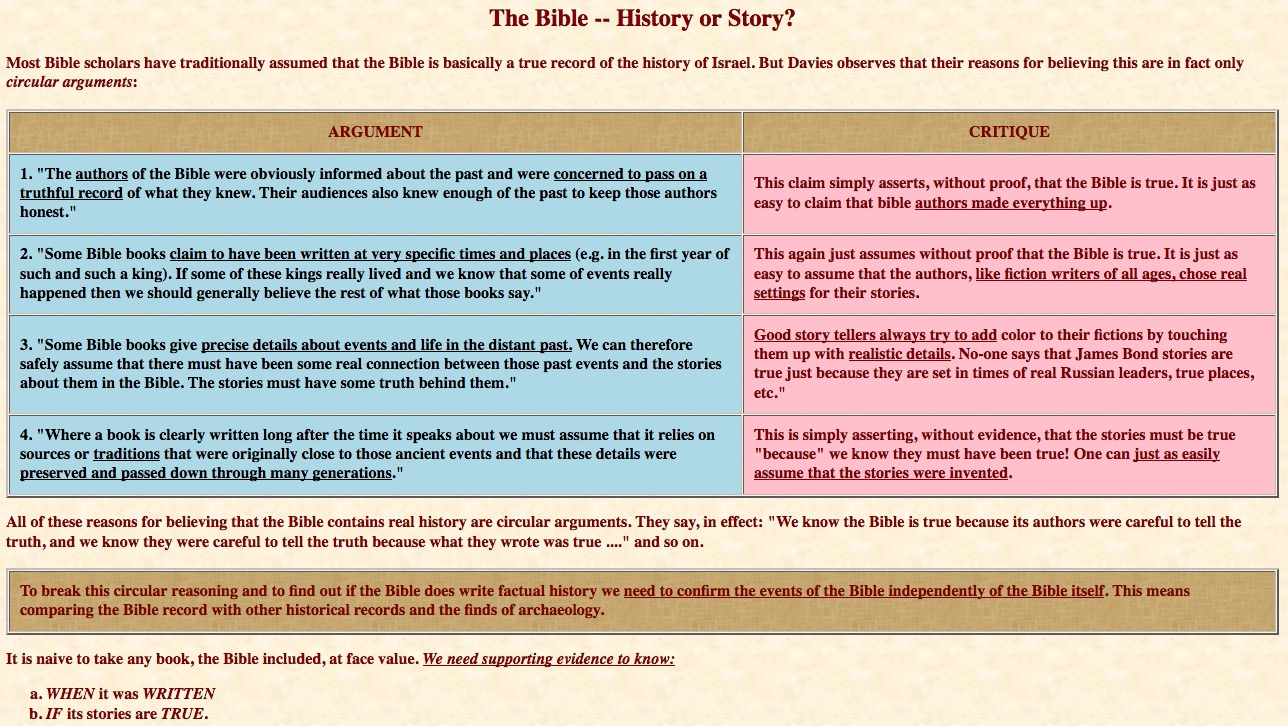

James McGrath began the discussion in a style that conveyed a serious analytical analysis of Carrier’s argument. Of course anyone who has read Carrier’s works knows McGrath’s target was a straw man and not the actual argument Carrier makes at all. (Interestingly when Carrier pointed out that it appeared McGrath had not read his actual arguments McGrath at best made inferences that he had read Carrier’s books but fell short of saying that he had actually read them or any of the pages where Carrier in fact argued the very opposite of what McGrath believed he had.) Nonetheless, McGrath’s opening gambit conveyed a positive approach for anyone unfamiliar with Carrier’s arguments.

But look what happened to McGrath’s analytical style after meeting Carrier’s less analytical style: he followed Carrier’s lead.

Carrier has chosen to write in natural language style which is fine for informal conversation but the first impression of an outsider unfamiliar with Carrier’s arguments would probably be that McGrath was the more serious analyst of the question. (I understand why Carrier writes this way but an overly casual style, I suspect, would appeal more to the friendly converted (who are happy to listen rather than actively share the reasoning process) than an outsider being introduced to the ideas.

In actual fact, Carrier uses far more words that do indeed point to analytic thinking than does McGrath. Carrier uses cognitive process words significantly more frequently than does McGrath (24% to 16%/19%). But his sentences are far less complex and shorter.

Other

There are many other little datasets that a full LIWC analysis reveals. One is a comparative use of the personal singular pronoun. A frequent use of “I” can indicate a self-awareness as one speaks and this can sometimes be a measure of some lack of confidence. Certainly the avoidance of “I” is often a measure of the opposite, of strong confidence and serious engagement in the task at hand. Carrier’s use of I is significantly less than McGrath’s.

Another progression one sees is the use of “he”. As the debate progressed it became increasingly focused on what “he” said: e.g. McGrath1: 0.45%; Carrier 1.65%; McGrath2 2.06%.

McGrath sometimes complains about the length of Carrier’s posts. But more words are linked to cognitive complexity and honesty.

—o—

Of course I could not resist comparing my own side-line contribution:

| VARIABLE |

NEIL

Reply

(1077 words) |

Analytic thinking:

(the degree to which people use words that suggest formal, logical, and hierarchical thinking patterns) |

86.42% |

Authenticity:

(when people reveal themselves in an authentic or honest way) |

44.36% |

Clout:

(the relative social status, confidence, or leadership that people display through their writing) |

56.27% |

Tone:

(the higher the number, the more positive the tone) |

32.13% |

Anger:

(measured by my use of “criticism”, “argument” and “critical”)

|

0.93% |

.

Pennebaker, James W. 2013. The Secret Life of Pronouns: What Our Words Say About Us. Reprint edition. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Like this:

Like Loading...