There is a mind game I sometimes play when assessing claims that the gospel authors used eye-witness reports as their sources. The game is to attempt to position oneself in the mind of the author as one reads, and to imagine with each word picture the author actually recalling the words of a reporting eye-witness. It is only a mind game and not a fool proof methodology, but it nonetheless can help one ask important questions in response to specific arguments for eye-witness sources.

Playing the mind-game

Take, for example, Mark 6:45-53, where Jesus walks on water:

And straightway he constrained his disciples to get into the ship, and to go to the other side before unto Bethsaida, while he sent away the people.

And when he had sent them away, he departed into a mountain to pray.

And when even was come, the ship was in the midst of the sea, and he alone on the land.

And he saw them toiling in rowing; for the wind was contrary unto them: and about the fourth watch of the night he cometh unto them, walking upon the sea, and would have passed by them.

But when they saw him walking upon the sea, they supposed it had been a spirit, and cried out:

For they all saw him, and were troubled. And immediately he talked with them, and saith unto them, Be of good cheer: it is I; be not afraid.

And he went up unto them into the ship; and the wind ceased: and they were sore amazed in themselves beyond measure, and wondered.

For they considered not the miracle of the loaves: for their heart was hardened.

And when they had passed over, they came into the land of Gennesaret, and drew to the shore.

When I read the first verse, “And straightway he constrained his disciples to get into the ship, and to go to the other side before unto Bethsaida, while he sent away the people”, I find no difficulty at imagining that it could have come from an eye-witness. Someone, a disciple presumably, was there with Jesus and the others, heard and saw Jesus tell him and his companions to get into the ship and row to Bethsaida, while he explained to them that he was going to send the crowds back home. One can imagine an author recalling the message of an eye-witness to all of this.

But with the next verse the game runs into a difficulty. How did that eyewitness, after having been sent off by Jesus with the other disciples, know that Jesus then went to a mountain, and went there to pray? The way it is written does not follow easily from my initial image of that eyewitness telling his story to the author. The only way I can make it work is to imagine that the eye-witness told the author that Jesus also said to them that after they left he was going to go up into yonder mountain for a bit of quiet prayer time. Possible, of course, but my initial image of clear-cut reporting to author is smudged a little to make it work.

Then in the opening of the third verse, I can again return to my image of the eye-witness relating how he was in the “ship” at “sea” when it grew dark. But the last part does not work its way easily into that same image. The eye-witness reports from his perspective what he sees and knows. The image of Jesus “alone on the land” does not come from an eye-witness in the boat at sea in the dark. The last this witness had seen of Jesus was when he was with crowds and ordering him to launch out and row to Bethsaida.

The image of Jesus alone on the land comes from the imagination of the author. He adds it into what he recalls from the eyewitness. But for him to do that, he must have some distance from what the time of the eye-witness’s narration and time to reflect to imagine a broader picture. The author had no reason to think Jesus was alone apart from what his own imagination suggested or inferred from what he had heard.

Next, it gets worse for maintaining the mind-game of imagining the author recalling his eye-witness account. He writes, “And he saw them toiling in rowing“. Now this is a clear instance of the author’s creativity. No eye-witness saw Jesus watching them row.

Continuing, the author wrote that Jesus “would have passed by them“. Again, this does not come from an eyewitness. An eyewitness witnesses actions, not intentions of the mind, least of all from a distance in the darkest morning hours. An eyewitness report might say that he walked past them, or appeared to be walking away from them, but not what he would have done. Again, we have authorial creativity at work here.

Finally, did the eyewitness really think at the time, or even afterwards at the time of his reporting to the author, that his and his colleague’s fear was the result of failing to understand the miracle of the loaves? It is hard to imagine. Otherwise, we should expect the same eyewitness to have explained the connection between that miracle and the water-walk, and for the author to have passed this on to his readers.

Conclusion of the author mind-game

This line is in fact a giveaway that the author is creating his own story with a cryptic moral for insiders to understand. It throws into sharper relief the earlier passages that had to have originated in the same author’s imagination.

The story, as it stands, does not come from an eye-witness. It is a bird’s eye narrative that contains images that could only come from the mind of a creative author.

Such a game does not, of course, prove there was no eye-witness involvement at any stage. But it does demonstrate that an eye-witness theory of origins of this story must also find a way to account for non-eyewitness data getting into the mix.

The more interesting play

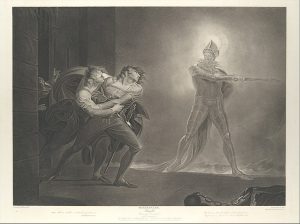

It gets much better, however, if we attempt to imagine ourselves being interviewed for our public claims to have seen a ghost at sea turn into Jesus.

If the original author ever toyed with such a mind-game himself he had enough sense to keep the narrative to the bare bones of what was required to teach the moral.