In order to gain possible insights into the origins of persons and events in the gospels, we have, over the past year and more, been attempting to read the Scriptures with the same types of “midrashic” mindsets that ancient Jewish scribes exercised. What follows is from Portrait d’Israël en jeune fille: Genèse de Marie by Sandrick Le Maguer. You may not be persuaded by all of what follows but I hope it will at least make us wonder about the possibilities.

In order to gain possible insights into the origins of persons and events in the gospels, we have, over the past year and more, been attempting to read the Scriptures with the same types of “midrashic” mindsets that ancient Jewish scribes exercised. What follows is from Portrait d’Israël en jeune fille: Genèse de Marie by Sandrick Le Maguer. You may not be persuaded by all of what follows but I hope it will at least make us wonder about the possibilities.

In Part 1 we saw that Miriam was associated closely with the miracle rock or “well” that produced flowing water for Israel as they wandered in the wilderness — the rock accompanying them on their trek. (The inspiration for this association arose from Numbers 20:1-2 we read first that Miriam died and then, in the following sentence, there was no water for Israel. Rabbis put two and two together and decided Miriam’s death had to be the reason: Moses this second time had to turn on the tap by speaking to the rock but, as we know, he struck it twice with his rod instead.)

Wisdom = Miriam = Well = Torah

Now early Jewish exegetes compared a well of water to the Torah, the Law. In Rabba Genesis 1:4 we find, as well, an equation of Wisdom with Law.

R. Banayah said: The world and the fullness thereof were created only for the sake of the Torah: The Lord for the sake of wisdom [i.e. the Torah] founded the earth (Prov. iii, 19).

The Hebrew word for well is “beer” (we wish!), as in Beersheba, etc., the three root consonants being beth, aleph, and resh: באר

If you feel uncomfortable introducing such a late source as Rabba Genesis then you may prefer instead to savour the Damascus Document from among the Dead Sea Scrolls. In 6:4 there we read the same interpretation, this time while discussing Numbers 21:18

The Well is the Law, and its “diggers” are the repentant of Israel who went out of the land of Judah and dwelt in the land of Damascus.

Now the same three root consonants (beth, aleph, and resh), in the same order, also mean to “make clear and plain”, as we read in Deuteronomy 27:8 in connection with how the Law was to be written:

And you shall write very plainly [באר] on the stones all the words of this law.

We can transcribe this as baar. The point is that, as Maguer would say, we here have an “over-determination” of the link between the Law and the well. What is written clearly, plainly, the root for the word “well”, is the Law.

So where does Miriam enter?

We recall from Part 1 that in Exodus 15:20 Miriam is called “the prophetess”: hanaviah [הנביאה] – ha=the, navi or nabi=prophet, ah=feminine ending.

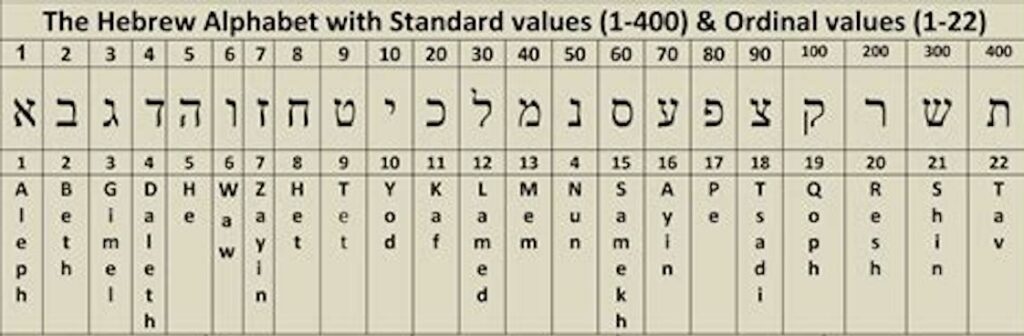

We have also seen indications that the numerical values in some words, or gematria, were an important element in rabbinic interpretations and that it is not unreasonable to think that this method was known very early. (Numerical techniques in the Gospel of John alone have been the subject of a monograph.) Now there are two types of gematria: one, row gematria, assigns a number in sequence from 1 to 22 to each of the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet; the other, classical gematria, does the same up to number 10 but then assigns multiples to the other numbers:

The row gematria value for “the prophetess” is 37; the classical gematria value is 73. A magical number, some might wonder.

The row gematria value for “the prophetess” is 37; the classical gematria value is 73. A magical number, some might wonder.

Now the word for wisdom in Proverbs 7:4 is chokmah [חכמה]. I am not taking this passage at random. We will see that it has a most significant connection with Miriam in rabbinic interpretations.

Say to wisdom [chokmah /חכמה ], “You are my sister,” And call understanding your nearest kin

It turns out that, you guessed it, chokmah, het or chet-kaf-mem-he, also = 37 and 73.

Midrash Exodus is a late writing but we will see what thoughts it contains nonetheless and perhaps wonder about the provenance of such ideas. Midrash Exodus or Shemot Rabbah 1:22 associates each word or phrase with others in the Scriptures to find a message about the close watch God was maintaining over the fate of Moses. We see that Miriam is equated with the “Sister Wisdom” that we just read in Proverbs 7:4 — following the passage we addressed in our earlier post that makes us wonder if the evangelist describing the women “far off” from the cross expected readers to recall the image of Miriam:

And this is why the verse says “And his sister stood by from afar”, for she wanted to know what would be the results of her prophecy. And the Rabbis say the entire verse was said with the Divine Spirit. “And she stood” similar to (1 Samuel 3:10) “And G-D came and stood”. “His Sister” similar to (Proverbs 7:4) “Say to wisdom, she is your sister”. “From afar” similar to (Jeremiah 31:2) “From afar G-D is seen to me”. “To know what will happen to him” similar to (1 Samuel 2:3) “For G-D is all knowing”.

So we have Wisdom=Law=Well . . . the prophetess Miriam.

We have not exhausted the well, though. Wisdom is, according to the Scriptures, hidden. In Job 28:21 …

It is hidden [ne-alamah / נעלמה ] from the eyes of all living, And concealed from the birds of the air.

Miriam “hid” her family relationship to the infant from Pharaoh’s daughter — according to that late Exodus Midrash 1:25.

But that word for “hidden” contains the same consonant roots — fair game for the wordplay that is the meat of midrash — as another description of Miriam, and a word that has become famous as the source for the prophecy of the virgin Mary. That word is “almah”, young girl or woman.

Then [the infant’s] sister [i.e. Miriam] asked Pharaoh’s daughter, “Shall I go and get one of the Hebrew women to nurse the baby for you?” Pharaoh’s daughter told her, “Go,” so the young girl [עלמה / almah] went and called the child’s mother. — Exodus 2:7-8

Here is the key passage:

Behold, a young woman [עלמה / almah] shall conceive, and bear a son [ןב / ben], and shall call his name Immanuel [עמנואל / Immanuel = 62/197]. — Isaiah 7:14

An aside: Maguer observes that “son of a young women” – ben almah – has the same gematria value as Immanuel.

While we are aside, Maguer further sees a possible suggestion in Proverbs 30-18-19 where another very rare word for ‘man’ is used:

There are three things that are too amazing for me, four that I do not understand . . . . the way of a man [רבג / geber] with a young woman [עלמה / almah].

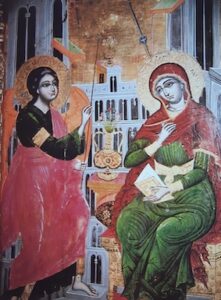

Was this the inspiration for Luke’s introduction of the angel named Gabriel meeting the “young woman” of Isaiah 7:14 to announce the miracle child she was about to have?

Are we right to imagine that the evangelists responsible for the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, in thinking of how to incorporate the prophecy of Isaiah 7:14, turned their minds to the most famous “almah”, Miriam, who was responsible for setting Israel’s former saviour on his vocation? Was this the origin of the name of Jesus’ mother, Mary? There are many other Hebrew words for a woman so it is significant that a focus on almah yields such possibilities.

Recollect part 1: Miriam was the mother of a spirit-filled child, Bezalel who was “full of wisdom”, responsible for the construction of the “house of God”, was the ancestress of the ideal messiah David, was a prophet. The evangelists surely knew that the messiah was to possess the “spirit of wisdom” according to Isaiah 11:2

The Spirit of the LORD will rest on him— the Spirit of wisdom and of understanding . . .

Yes, but! A young woman is not necessarily a virgin. So how do we get to the virgin Mary? Two ways.

The first way: we read of another famous “almah” in Genesis 24:43, Rebekah. I refer you to the link that will take you to a page where you will see several biblical translations opting for the word “virgin” to describe Rebekah who is about to meet Abraham’s servant at the well. The word so translated is “almah” — as you can see at this link. The translators presumably felt justified in using the word “virgin” because Rebekah had been explicitly described as such a few verses earlier: 24:16.

The second way: we return to that condensed passage from the late Exodus Rabbah but this time with a different focus . . .

And this is why the verse says “And his sister stood by from afar”, for she wanted to know what would be the results of her prophecy. And the Rabbis say the entire verse was said with the Divine Spirit. “And she stood” similar to (Samuel 3:10) “And G-D came and stood”. “His Sister” similar to (Proverbs 7:4) “Say to wisdom, she is your sister”. “From afar” similar to (Jeremiah 31:3) “From afar G-D is seen to me”. “To know what will happen to him” similar to (1 Samuel 2:3) “For G-D is all knowing”.

So we turn to Jeremiah 31:3 to find what this passage has to say and what light it might shed on Miriam:

The LORD appeared to him from afar, saying, “I have loved you with an everlasting love; Therefore I have drawn you with lovingkindness. “Again I will build you and you will be rebuilt, O virgin of Israel! Again you will take up your tambourines, And go forth to the dances of the merrymakers.

As God looked on Moses “from afar” through Miriam so he looks on a “virgin of Israel” who, like Miriam, took up the tambourine and danced as the prophetess of Exodus 15. We may not want to give too much weight to a late rabbinic source, but we can use its lights to see what was possible — if not already part of some thinking at the time — to persons poring through the Scriptures in search of the narrative behind the birth of Jesus.

Another aside: Maguer finds in the name of the Rebekah “almah”, mother of Jacob, the same roots for the word “tomb”

Rebekah = [קהבר / Ribqah] ר qbr tombקב

Rebekah learned that she had “two nations” in her “womb” (the word is closer to “entrails”, “innards”)

Genesis 25:22 “womb” within / qrb / קרב

And this brings us to the other Marys in the gospels. Where do they all come from?

One, like Rebekah, is the mother of a Jacob (=James). Another is Mary Magdalene.

There were also women looking on from afar, among whom were Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James [=Jacob] the Less and of Joseph, and Salome, who also followed Him and ministered to Him when He was in Galilee, and many other women who came up with Him to Jerusalem. . . . And Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Joseph observed where He was laid. . . . Now when the Sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of Jacob, and Salome bought spices, that they might come and anoint Him. — Mark 15:40-41, 47, 16:1

Here I depart from Maguer and offer a few brief thoughts.

Miriam is said to mean “bitter” or at least it is related to the word for “bitter” as we read in Exodus 15:23

Now when they came to Marah, they could not drink the waters of Marah, for they were bitter. Therefore the name of it was called Marah.

Surely it is no coincidence that we have two Marys appearing at that most bitter of climaxes, the crucifixion. But there is also a Salome there, peace.

Magdala is a tower, including a watchtower that would be set up to keep an eye out for predators threatening herds. I think of the tower as a symbol of the city of Jerusalem or its Temple. And especially of the prophecy of Micah 4:8

As for you, watchtower of the flock,

stronghold of Daughter Zion,

the former dominion will be restored to you;

kingship will come to Daughter Jerusalem.”

That is the promise. But the scene in Mark 15:40 is the bitter one of Mary Magdalene watching from afar with the other women (“the daughters of Israel?) the momentary destruction of that tower, the “daughter of Zion”

He built a tower in its midst,

And also made a winepress in it;

So He expected it to bring forth good grapes,

But it brought forth wild grapes.

. . . .

I will take away its hedge, and it shall be burned;

And break down its wall, and it shall be trampled down.

I will lay it waste . . .— Isaiah 5:2-6 (Recall that Jesus is the personification of Israel)

Mark 15:40-41 leads us to understand that the two Marys and Salome are representative of many women present at the crucifixion. Is it a coincidence that when Joseph of Arimathea is laying Jesus in the tomb one of the Mary’s present is said at that moment to be the “mother of Joseph”? When Mary is looking from afar at the cross she is said at that moment to be the mother of Jacob “the less” and Joseph, but when she is coming to anoint with spices the body of Jesus she is said to be “the mother of Jacob” (no “less”). Is the former meant to lend some significance to the moment of the crucifixion while the removal of the diminutive is thought to be appropriate when coming on the scene of the resurrection? Maybe the details of the original symbolism have been lost forever now. But the odd way of framing the mother through her children expressed in different configurations at different stages of the narrative surely had some significance for the original readers.

We will probably always be finding new associations with these names in the Hebrew Scriptures and be led to wonder, “Is that what came to the minds of the authors? of their audiences?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Both the Toledot Yeshu and the Arabic-Syriac lexicon of Bar-Bahlul identify Magdalene as being derived from “gadal”, meaning to dress hair, which was typically used as a euphamism for prostitution. In the Toledot, she was Jesus’ mother, which probably means the Virgin Mary and Mary Magdalene were originally the same harlot figure. Free-thinking Gnostics took her and mythologized her with the Sophia and wrote about her having seven powers, which Conservative historicists then rewrote into her having seven demons that needed to be exorcised.