I have been asked to address certain arguments on another forum and thought I’d draft out this one here as something of a prep.

. . . I was asked if I am “sure” Jesus existed as a historical figure, and if so why. I tried to give a short answer as follows:

“Sure” is relative. I’m as confident as one can be for a figure in the ancient world who did not mint coins or erect edifices on which he placed inscriptions about himself.

The shortest argument (which, like a short argument for anything, may not seem persuasive unless it is expanded on) is this:

– the anointed one descended from David referred to the king and the restoration of that line to the throne

– being executed by the Romans before establishing one’s throne disqualified one’s claim to be the one to restore the Davidic dynasty to the throne

Therefore

– It is less likely that early Christians invented from scratch a crucified anointed one and went around trying to persuade their fellow Jews to accept him, than that there was a figure that they believed to be this messiah who was then executed, and they managed to maintain that belief despite the cognitive dissonance resulting from this counterevidence.

(From Mythicism and the Bacterial Flagellum, and from the discussion at A Popular Blunder . . . )

McGrath is careful to point out that these few words are only a short form of the argument, but fortunately he had more opportunity in a lengthy discussion to expand on some of the points. To underscore aspects of this argument he elsewhere stated:

Paul was trying to persuade his contemporaries that a crucified man was nonetheless the restorer of the Davidic kingship. . . .

. . .

The Davidic anointed one was the awaited king that it was hoped would restore his dynasty to the throne and usher in a golden age of one sort or another. Being crucified pretty much disqualified you from being the person in question. Is it probable that a group that was concocting a message about the long-awaited king, which they planned to proclaim to others in order to persuade them to believe, would also invent that this individual was executed and thus at least apparently a failure and a thoroughly implausible candidate for the role? . . . .

. . .

In response to your last question, it is unlikely that if someone is inventing a Davidic Messiah that they plan to ask people to believe in, they will invent a failed one. . . .

. . .

You hadn’t seemed to yet have grasped my extremely basic point about the unlikelihood of a group having invented a crucified Davidic messiah as the focus of a belief they wanted to convert their fellow Jews to. . . .

(from the discussion at A Popular Blunder . . . )

Cognitive dissonance indeed! A crucified failure as the conquering Davidic messiah?! It would indeed take a miraculous intervention to get Christianity started from that foundation.

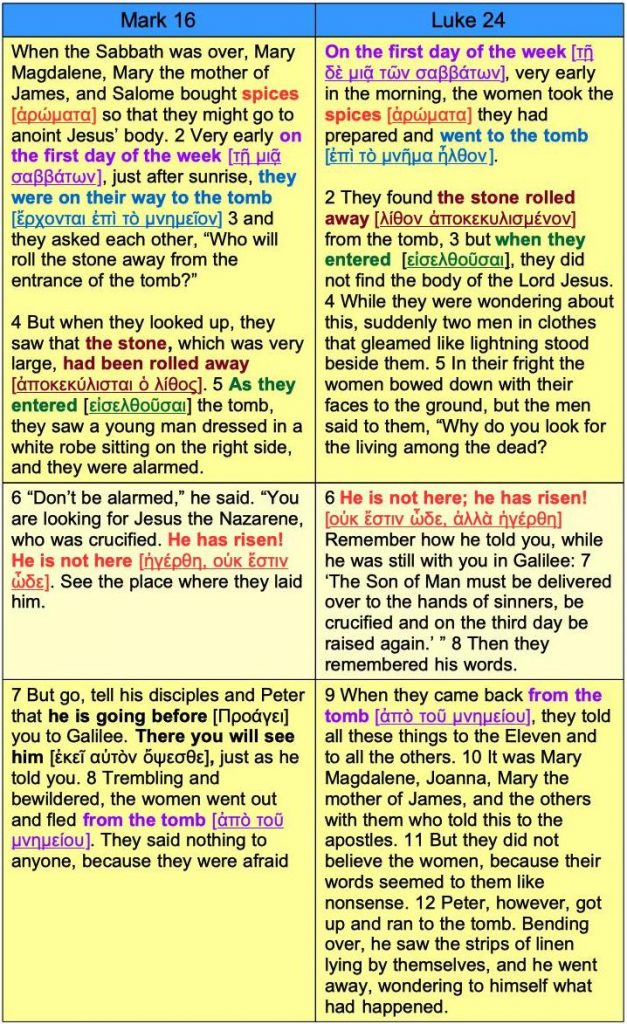

But is not the whole argument based on a misreading or very distorted reading of our evidence?

Let’s start with Paul. I’ll set aside problematic questions of interpolations and authenticity and assume the passages I quote are all genuinely Pauline.

Paul says in Romans 1:3 that Jesus was “having come of the seed of David according to the flesh / γενομένου ἐκ σπέρματος Δαυεὶδ κατὰ σάρκα”. Let’s set aside all the known oddities associated with that passage and just accept that Paul was saying that Jesus was born as the principal heir to David.

Now in 1 Corinthians 15 we find Paul making other associations between Jesus and David. Paul applies the Davidic Psalms 110 and 8 to Jesus. In Psalm 110 David sings:

The Lord says to my lord:

“Sit at my right hand

until I make your enemies

a footstool for your feet.”The Lord will extend your mighty scepter from Zion, saying,

“Rule in the midst of your enemies!”

In Psalm 8 David writes

thou hast put all things under his feet

and Paul applies that passage to the David Messiah’s rule.

Paul makes it clear that Jesus has fulfilled that Davidic hope by multipliers. I Corinthians 15:17-26

And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile . . . But Christ has indeed been raised from the dead . . . when He comes . . . Then the end will come, when he hands over the kingdom to God the Father after he has destroyed all dominion, authority and power. For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet. The last enemy to be destroyed is death.

With 15:25 Paul says, “He must reign until He has put all His enemies under His feet” (25). The “must” means it is necessary that Jesus reigns. Paul’s wording in verse 25 is a reference to Ps 110:1–2 . . . .

Paul is interpreting Ps 8:6 both literally and christologically. . . . Corporate personality is in view here. Psalm 8 is addressed to man in a general sense, but since Jesus is the ultimate Man and last Adam, He represents man. As Mark Stephen Kinzer notes, “The psalm is read in both an individual and a corporate sense.” The use of Psalm 8 is further evidence that Paul is thinking of a future earthly reign of Jesus.

Vlach, Michael J. 2015. “The Kingdom of God in Paul’s Epistles.” The Master’s Seminary Journal 26 (1): 59–74.

Paul did not pick up on the “cognitive dissonance” of the first apostles. What was being preached was that Jesus, through death and resurrection, had become the ultimate fulfilment of the all-powerful and cosmos-ruling Davidic Messiah.

When we come to the gospels “fleshing out” a Jesus narrative we find that even the lead up to the crucifixion is thoroughly Davidic.

The evangelists appear to have modelled Jesus on the David who was first and foremost a pious exemplar who suffered. David was renowned as the psalmist who suffered for righteousness. It is in that capacity that Jesus quotes David’s words. David was God’s anointed (messiah) but notice what this meant for him —

In the Psalms attributed to him, he cries out to God as one forsaken and persecuted. (Pss 18, 142). In Psalm 22 he cries out in pious agony, My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?

David’s career is one of fleeing from persecution. He is the chosen and pious, righteous sufferer. His persecution is a badge of his honour, not shame, in the eyes of all who look to him as a model of piety. He is betrayed by his closest followers and ascends the Mount of Olives to pray in his darkest hour. He prepares for the building of the future temple after his death. If early Christians ever thought to apply the Davidic motifs to Jesus, they surely did so with remarkable precision. David may have ruled a temporal kingdom, but Jesus demonstrated his power over the invisible rulers of the entire world. Even though ruler over the princes of this world, he was still betrayed, deserted and denied by his closest followers. He ascended the Mount of Olives in prayer at his darkest hour. And he suffered the injustice that the righteous have always proverbially suffered, even crying out with David, My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? But as in the Psalms God delivered David from the depths and pits of hell to exalt him in vindication before his enemies, so did God deliver and exalt Jesus. What was the suffering of humiliation in the eyes of his enemies has always been the badge of honour in the eyes of God and devotees.

Conclusion

So did the first disciples struggle with cognitive dissonance over attempting to maintain a belief that a failed, dead, crucified man was the Christ of their salvation? Did they somehow manage to convert enough followers to start a new religion by preaching that a dead failure was the Christ?

Is that really an argument to make one “sure” of the historicity of Jesus? That a man had such power that he could persuade his followers to believe in him and convert others to that same belief even though he clearly failed in his mission?

Certainly, “– being executed by the Romans before establishing one’s throne disqualified one’s claim to be the one to restore the Davidic dynasty to the throne” would disqualify a messianic claimant. But that’s not what Paul of the first Christians appear to have believed for a moment. They believed that it was through crucifixion that Jesus conquered the powers of death and would come to finish the task by conquering his human opponents in the final judgement. Rather, crucifixion qualified Jesus and this was proven by his resurrection.

Now, back to the question of historicity.

No one argues that the story was “invented from scratch”. The evidence points to a story coming together as a result of emerging Second Temple era interpretations of Jewish scriptures (e.g. the evolution of a suffering servant and son of man messianic figure from Isaiah to Daniel to Enoch). The first believer we have a record of boasts that his belief came about entirely through visions and from that foundation he made converts. Only decades later does a “fleshed out” story in our gospels, set in a time and place no longer accessible to most readers, emerge.

That does not prove Jesus was not historical. But it sure leaves the door to the question somewhat ajar.