Forget any notion of an anti-Roman “nationalism” yearning to be free from Rome. Forget messianic hopes and a desire to be ruled by God alone. Steve Mason proposes in A History of the Jewish War, A.D. 66-74 causes much more common to wars more generally:

Forget any notion of an anti-Roman “nationalism” yearning to be free from Rome. Forget messianic hopes and a desire to be ruled by God alone. Steve Mason proposes in A History of the Jewish War, A.D. 66-74 causes much more common to wars more generally:

The Judaean-Roman conflict broke out … not from anti-Roman ideas or dreams among the uniquely favoured Judaean population, but from the sort of thing that more commonly drives nations to arms: injury, threats of more injury, perceived helplessness, the closure of avenues of redress, and ultimately the concern for survival.

(Mason, 584)

Further, there was no massive Judean wide uprising against Rome. Most Judeans either quickly demonstrated their loyalty to Rome or fled for their lives as Nero’s general Vespasian approached. Prior to the siege of Jerusalem, Vespasian’s army “faced little or nothing in the way of combat” (412). [Some readers will immediately be wondering about Joseph Atwill’s account and in particular the “battle of Gadara” will come to mind. At the end of this post I add Steve Mason’s description of that massacre and its context in the “wider war”.]

I’ll attempt a very general overview of what Mason proposes were the steps that led to the war. Doing so means I necessarily gloss over the detailed reasons for each point he makes and for his setting aside the conventional view that Judean resentment against Rome was on the boil until it reached a point where open rebellion was inevitable. So take the following as an invitation to read the book or follow up with further discussion wherever appropriate.

The theme to look out for running through each of the following stages is the tense relationship between Judeans and their neighbours.

Before Rome

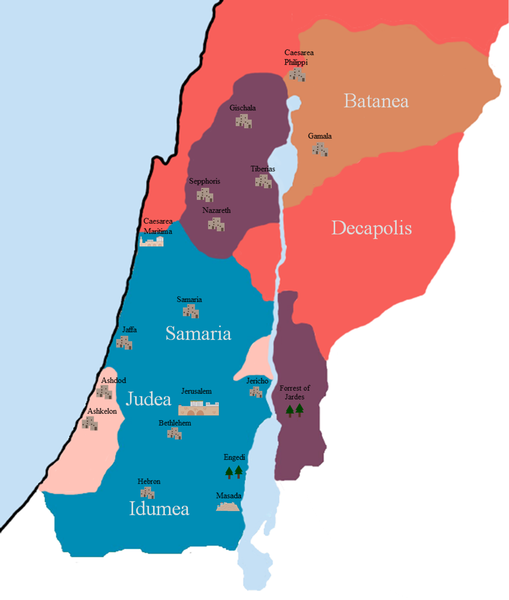

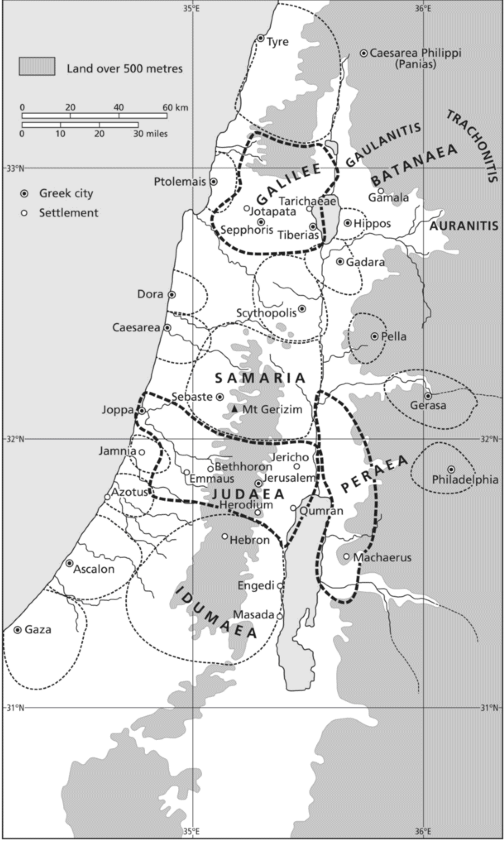

Before the Roman period Judea was a regional hegemon. This had been the work of the Hasmonean dynasty that cowered neighbours — Samaria, the Mount Gerizim temple, cities of the Decapolis — into submission by conforming to Jewish ways or destroyed them.

Rome Enters

The Roman Pompey was thus greeted as a liberator from Judean domination. Pompey reduced Judea to little more than its pre-Hasmonean extent.

Not long afterwards, however, Herod was made a client king of Rome and Judea once again became the regional hegemon. (Mason argues that Judea was not a Roman province at this time but was an ethnic region of southern Syria. Syria itself was a Roman province. Judea did not become a Roman province until after the Jewish War.)

So Herod’s Kingdom of Judea was permitted to extend even beyond what it had been during Hasmonean times. Unlike the Hasmoneans, though, Herod did not attempt to Judaize his neighbours. Samarians and Idumeans were permitted their own institutions, cultures and cults.

Herod Dies

Herod died and the Roman emperor Augustus respected his will that his kingdom be divided among his three sons:

Archelaus turned out to be the black sheep of the family and soon lost the support of key groups among his subjects. Pleas to Augustus for his removal succeeded.

(IN)SIgnificance of Judas the Galilean

Josephus informs us that after the removal of Archelaus there arose (6 C.E.) “a certain Galilean fellow by the name of Judas” who attempted to instigate a rebellion and calling for no ruler but God alone! Mason challenges the common view that this Judas marked the beginning of Judea’s “nationalist” movement for freedom from Rome:

Solomon Zeitlin put the standard view succinctly: “The Sicarii were the followers of the Fourth Philosophy which was founded by Judas of Galilee in the year 6 CE.”170 To untangle the knot of assumptions behind this, we must reconsider the evidence. Fortunately, there is little. (Mason, 245)

Mason focuses on the timing of the protests. That a protest movement began soon after the removal of Archelaus and the incorporation of Judea into the province of Syria (an event that would have entailed a census on Judea) is not likely coincidence. It is not likely that anti-Roman feeling suddenly flared up at this point after having been in effect for seventy years by this time. The other regions where there was no change, those that continued under Antipas and Philip, saw no uprising.

No, according to Mason, any form of revolt at this time is best understood as a change in the status of the Judeans as they were incorporated into the province of Syria and their centre of administration moved to Caesarea. That involved a major shift in relations with neighbouring ethnic groups as we see in the next section.

turning point — Caesarea and a samarian force dominate

With the removal of Archelaus the centre of administration shifted from Jerusalem to Caesarea.

Herod’s army had been a “multi-ethnic” organization but with the removal of Archelaus the armed forces that were the means of maintaining order lost their large Jewish component and became predominantly Samarian.

In other words, with Caesarea now the administrative centre, a Samarian force was set over the Judean population.

We have seen from the above how historically there were tensions between the Judeans and her neighbours. Now it was the Judeans turn to take the subordinate place.

Jerusalem’s regional status remained the central question during the next six decades.

(Mason, 582)

Peace and justice for the Judeans and Jerusalemites were from that moment the responsibility of the equestrian commander of the auxiliary force based in Caesarea.

With Archelaus’ removal and Jerusalem’s loss of status, Samarians wasted no time in testing the new situation. At Passover in the spring of A.D. 7 or 8, while . . . an auxiliary cohort was supposedly watching Jerusalem, Samarians entered the temple precinct at night and scattered human bones in the colonnades and Court of Nations. Because this defilement rendered the sacred precinct unusable, the priests had to evacuate everyone, purify the site (perhaps losing the major festival that year), and institute better security measures. This may be the origin of the office of temple commandant/general (στρατηγός) and guards who reported to him on temple-mount activities. . . . In this case the auxiliary garrison at the very least turned a blind eye, if they did not facilitate the Samarian raid (Ant. 18.29—30). The first prefect in Caesarea . . . was recalled to Rome “shortly after” (18.31).

This episode contains the main ingredients of the next six decades of conflict: simmering Samarian-Judaean antagonism, (arguably) a pro-Samarian auxiliary, and the risk that an equestrian governor would either go native with his troops or be insufficiently sensitive to Judaean interests. But in this case, higher Roman authorities intervened and the incident blew over.

(Mason, 264 f. My emphasis in all quotations)

Pilate can be discussed at length but a brief summary of Mason’s view is that he was recalled to Rome from Judea after Samarians complained of his repeated cruelty towards them.

Whether he was a nice man we do not know, but his coins and behaviour seem designed not to offend Judaean law and custom. Pilate was eventually removed in 37 because of Samarian complaints about routine brutality toward them. The legate L. Vitellius, who sent him packing, was evidently solicitous of Jerusalem, visiting regularly at Passover and dispensing favours in recognition of warm loyalty.

Mason, 583)

Around the year 50 CE Samarian-Judean tensions again broke into violence (from p. 271):

- An [Samarian] auxiliary soldier’s provocative insults to Passover pilgrims in the temple court incites Judaean youths to rock-throwing, which gives the soldiers a pretext to react with force.

- In a search for Judaean bandits in the Judaean countryside after a Judaean robbery, an auxiliary soldier finds a copy of the Torah and burns it.

- One or more Galileans travelling to Jerusalem is/are killed in Samaria near modem Jenin (Ginae).

The last-mentioned “incident” becomes a microcosmic image of the later events that led to the final outbreak of war with Rome:

- Judeans plead with the Roman governor to punish the Samarian murderers;

- The Roman governor was believed to have done nothing in response;

- Judeans take “justice” into their own hands and burn Samarian villages neighbouring Judea;

- Meanwhile, Jerusalem elders plead with their people to stop attacking Samarians lest Rome intervenes against them;

- The Roman governor responds by leading the Samarian auxiliary force against the Judeans . . . .

Mason concludes that had “Judaean vigilantism against Samarians … escalated as it would a decade later . . . ‘the Jewish revolt against Rome’ could have begun there and then in the early 50s:

In that case it would have been clear that the war arose from regional aggravations.

(Mason, 272)

anti-Roman sentiment A driver towards war?

There is no need to deny some measure of anti-Roman sentiment among Judaeans ever since 63 B.C., although it has left few if any traces. And one could presumably have found resentment among Samarians, Ascalonites, Gadarenes, Scythopolitans, and Nabataeans. But such grumbling does not usually start wars against great powers. The Judaean-Roman conflict broke out, I have argued, not from anti-Roman ideas or dreams among the uniquely favoured Judaean population, but from the sort of thing that more commonly drives nations to arms: injury, threats of more injury, perceived helplessness, the closure of avenues of redress, and ultimately the concern for survival.

(Mason, 584)

What changed in the 60’s CE?

What changed was Nero’s coming of age and his throwing off the advisors and tutors of his youth.

But once he reached maturity around 59/60 and shed his overseers by various means, Nero took a much-discussed turn. He became increasingly obsessed with art and revenue, the need for the latter exacerbated as his government weakened through fire, fear, and intrigue. In the early 60s he sent Lucceius Albinus and then Gessius Florus with a mandate to transfer as much money as possible to the imperial treasury.

(Mason, 584)

Caesarea was a flashpoint, Mason writes. It was the home of the Samarian dominated auxiliary forces and the centre of the imperial cult. The Judeans were a minority there, and both prosperous and increasingly vulnerable, especially with Nero’s reported contempt for Judeans and with Florus now entering to collect as much gold and silver as possible.

When Nero dispatched Gessius Floras to Caesarea in 64, the elements of a perfect storm were gathering. Florus’ mandate for ruthless revenue collection from Jerusalem’s temple with its world-famous wealth … made the nightmare scenario a reality. Judaeans now faced an auxiliary army itching to have free rein against them, with little constraint from the equestrian prefect if they resisted his efforts to seize temple funds, which they would inevitably do (War 2.277—344). Florus appears to have fully exploited the existing hatreds to intimidate and silence Judaeans or worse.

(Mason, 275)

The Judeans in Caesarea desperately begged Rome to allow Caesarea to be recognized as a Judean city. But Nero flatly denied their request. Nero had no patience for Judean complaints about the Samarian force dominating and apparently showing unjust bias against them.

To protect the temple younger priests, ignoring the advice of their elders and the Pharisees, used the temple force to prevent all foreign access to the temple. This act broke with the custom of the temple having allowed sacrifices by all ethnic groups.

The new governor, Cestius, is barraged with complaints about Florus but Florus tells him that it is the Judeans who are in revolt against Roman authority.

Josephus is most outraged that Florus went so far as to not only crucify commoner Judeans but even Judeans of his high social rank, even Roman citizens!

So the people of Judea were outraged both against the new burdens Florus was ruthlessly imposing and the Samarian auxiliary force acting on his behalf. They petitioned king Agrippa to send an embassy to Nero to demand the removal of Florus and to demonstrate that Jerusalem was not at war with Rome. Agrippa refused, apparently believing action would backfire.

Result: popular revolt drove Agrippa out of Jerusalem. Agrippa then with the governor of Syria, Cestius, prepared to march on Judea and Jerusalem to demonstrate to Judea that Rome was still in control and punish those who had already taken up arms. But events overtook them. Violence erupted between soldiers and Judeans. A garrison in Jerusalem was massacred, Jews in Caesarea were slaughtered, and Judeans who felt abandoned by normal channels of justice retaliated violently.

The Judeans’ problem was with Nero’s agent Florus and the Samarian force he used to enforce his plunder. Many of the Judean leaders attempted to assure the Roman governor that they were not opposed to Rome, but only the unjust Florus and his use of Samarian auxiliaries to rob them.

They knew that the auxiliary and Florus were the problem, but a subject population could under no circumstances use violence against a Roman force. For the sake of regional stability and for Nero’s eyes, Cestius would have to make a show of punishing culprits, while quietly trying to restore the ruling consensus with Jerusalem’s and other elites.

Cestius now had to thread several needles, showing a strong hand while creating peace. The danger of confusing his audiences and signals was great. Then word reached him of the garrison massacre in Jerusalem, the slaughter in Caesarea, and Judaean retaliations for the latter. Cestius had to intensify the punitive side of the expedition, allowing his legionaries to bum and destroy (mostly emptied) Judaean villages. But Sepphoris welcomed his garrison and assisted him in identifying militants. His intimidating measures became more severe as he moved southward, climaxing in the destruction of Joppa. But still he and Agrippa expected to be welcomed in Jerusalem. . . .

(Mason, 585)

Nero lost confidence in his governor Cestius and the king Agrippa to solve the problem so sent the general Vespasian to restore order by a display of punishment for violence against Rome’s agents and forces.

As soon as Vespasian arrived in Syria (early in 67), nearly the entire region welcomed him and Agrippa II, declaring their peaceful intentions. Delegates came from Judaean Sepphoris on behalf of Galilee, Tiberias among the king’s dependencies, the Decapolis cities, Samaria, and the coastal towns. Even before Titus had arrived with his legion, his father enjoyed nearly complete territorial control.Any potential regional war was largely over in principle at this point. As his army ranged undisturbed across Galilee, Samaria, and the coastal plain to Caesarea, many or most villagers deserted their homes in droves from fear. Many were afraid to risk falling into the legionaries’ hands. Vespasian allowed his army a measure of display violence, now to include demonstrable vengeance for Cestius’ losses. Judaean land and property suffered terribly, but because people had time to flee – to Sepphoris, King Agrippa’s territories beyond Vespasian’s purview, or points farther east — relatively few lives were lost. (Mason, 586)

There was no war to speak of until Vespasian reached Jerusalem. Jerusalem elites who otherwise would have submitted were unable to do so since they were effectively hostage to rebels groups that had fled to Jerusalem for refuge.

As Vespasian moved south to Caesarea (winter 67/68), the pattern of preemptive submissions continued. The leaders of Peraea and Judaean towns offered submission, even as the villages again emptied from fear of the army. Jerusalemites of means also rushed to Vespasian. Their native leaders were seeking a safe way for the polis to submit, but their situation was complicated. Jerusalem had already become a haven for refugees, including some such as John who could not or would not surrender. The ruling elite could not simply capitulate, and they faced a serious dilemma. Along with the perils they faced in the city for any perception of betrayal, their reception by Vespasian was not a given. They had much explaining to do.

While the city leaders were making their plans, the arrival of more armed factions made their handwringing superfluous. An emerging coalition of Disciples (Zealots) appealed to Idumaeans, who had a complicated relationship with Jerusalem, to defend the temple. The Idumaeans answered the call and murdered the chief-priestly leaders. Along with the other newcomers they dramatically changed the city’s profile. From A.D. 68 onward, Jerusalem was in the hands of factions, mainly from elsewhere, who could not easily turn back.

Vespasian’s nearly immediate domination of southern Syria makes it difficult to accept either that a province of Judaea revolted or that the wartime coins reveal an independent rebel state from 66 to 70 (Chapters 4, 7). From the spring of 68 at the latest, only the walled city of Jerusalem and its agricultural hinterland were not under direct Roman control.

(Mason, 587)

What about the messianic hopes of the Jews? That question was discussed in the earlier post, Is Josephus Evidence that a Messianic Movement caused the Jewish War?

The “Battle at Gadara”

While Vespasian winters in Caesarea, many native Jerusalemites flee to him. They assure him that much of Jerusalem’s real populace has remained loyal and would similarly like to make contact, but those trapped inside are being restrained by tyrants from outside who have killed the city’s leaders. These fighters are preventing all who cannot afford bribes from leaving. The violent men have even ordered that corpses remain unburied on the road out of Jerusalem — recall Creon in the Antigone — as a grisly warning to defectors.

In about February 68, the earliest moment for military activity after winter, Vespasian’s first move is characteristically not against Jerusalem. He crosses Samaria to the north and the Jordan River into Peraea — the most neglected Judaean district in modem research. The wealthy elite of Peraea’s largest town are among those who have sent an embassy to him in Caesarea, while dismantling their walls in a show of eager cooperation.16 As the Romans are on the way to consolidate this area with a garrison, some local unreconciled men in the town panic and murder their most prominent man, abusing his corpse in the process. The standard pattern ensues: Vespasian garrisons the town without bloodshed and returns to Caesarea with his main army. He delegates the always eager Mr. Gentle (Placidus) to make an end of the town’s belligerent refugees (4.413-19).

Placidus’ 3,500-strong force, using a manoeuvre to draw his prey out of another village, cuts them down and bums the place. The survivors make for Jericho, west of the Jordan, terrifying all the villagers they meet along the way with news that the Romans are coming with a vengeance. Because no one imagines that a Roman force in this mood will worry much about distinguishing the guilty from the innocent, this news causes nearly everyone to panic and head for the river, which they are however unable to ford. Placidus catches up with them and destroys thousands, while also taking prisoners. The superfluity of corpses chokes the mighty river for some time (4.420—36).

(Mason, 411 f)

Mason, Steve. 2016. A History of the Jewish War, A.D. 66-74. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Thank you for this post which is a very good invitation to read the book.

Below is another review about the book. It complements your post and also draws attention to the fact that Josephe is not a reliable source.

Here is the excerpt

https://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2017/2017.02.51

Chapter 2, “Understanding Historical Evidence: Josephus’ Judean War in Context,” situates Josephus’s War as a work of Roman literary art,

warning against the modern temptation to approach it as a trove of data:

“It should now be clear why [Josephus’s] literary effort could never be reliable for us. We might as well ask whether a song or a mountain is reliable…

[The modern] longing for safe, unskewed data is not only a mirage but a recipe for misery. A realistic approach to Josephus’ work is far more interesting” (136).

Here are some tidbits that may be of interest:

• Following the Roman conquest of Judea led by Pompey in 63 BCE, Aulus Gabinius, proconsul of Syria, split the former Hasmonean Kingdom into five districts of legal and religious councils known as synedrion (in Jewish context better known as Sanhedrin) and based at Jerusalem, Jericho, Sepphoris (Galilee), Amathus (Perea) and Gadara (either Perea—Al-Salt, Decapolis—Umm Qais, or biblical Gezer, mentioned by Josephus under a Hellenised form of its Semitic name, Gadara, edited to “Gazara” in the Loeb edition).

• Both Galilee and Perea were Incorporated into “Greater Judea” i.e. Provincia Ivdaea in 44 CE, which already incorporated the regions of Samaria, Idumea, and the eponymous Judea. The regional name Perea is used by Josephus (c. 75 CE) and Pliny the Elder (c. 75 CE) in their geographic descriptions of the regions within the Ivdaea province.

I don’t know where these are from, but Mason lists many reasons for doubting that Judea was a Roman province until after 70 CE.

There is a dispute about when it “officially” was called Palestine.

•

“Timeline of the name “Palestine””. Wikipedia.

• c. 40 CE: “Philo: Every Good Man is Free”. earlychristianwritings.com.

I think we are talking about different things. Mason discusses his detailed reasons Judea was not a Roman province until after 70 CE. I was referring to your comment re Provincia Ivdaea in 44 CE. I still don’t know where those points came from or their relation to the post, sorry.