My original plan for a single post has now stretched out into four. Time to wrap up with Russell Gmirkin’s explanation for the relationship between the Solomon narrative and Assyrian records of Shalmaneser’s ninth century conquests and subsequent (eighth century) Assyrian building accounts.

My original plan for a single post has now stretched out into four. Time to wrap up with Russell Gmirkin’s explanation for the relationship between the Solomon narrative and Assyrian records of Shalmaneser’s ninth century conquests and subsequent (eighth century) Assyrian building accounts.

The close correspondence between Sennacherib’s building account of Solomon’s temple and palace suggests that the biblical authors were not only broadly familiar with the literary conventions of Mesopotamian building accounts but had actually read the cuneiform inscriptions at Sennacherib’s Palace Without Rival. One may posit Assyrian authorship of the building account in Kings by educated Assyrian or Babylonian scribes from Samerina who travelled back to Nineveh for the international celebrations associated with the Palace Without Rival (LAR, II, §§367, 394, 413, 424; cf. Russell 1991: 260-2).

(Gmirkin, 86)

The Method Behind the “Narcissistic Madness” of Kings

Through citations of primary and secondary sources Gmirkin directs readers to an explanation of the political propaganda functions of the Assyrian monuments with their boasting inscriptions, unparalleled architecture and grandiose sculptures. Sennacherib made it clear that the “glory” he displayed in his monumental works were meant to be seen by people coming from all parts of his empire:

367: Great slabs of limestone, the enemy tribes, whom my hands had conquered, dragged through them (the doors), and I had them set up around their walls,— I made them objects of astonishment.

394: Those palaces, all around the (large) palace, I beautified; to the astonishment of all nations I raised aloft its head. The “Palace without a Rival,” I called its name.

413: I placed pillars of maple, cypress, cedar, dupranu-wood, pine and sindu-wood, with inlay of pasalli and silver, and set them up as columns in the rooms of my royal abode. Slabs of breccia and alabaster, and great slabs of limestone, I placed around their walls; I made them wonderful to behold. That daily there might be an abundant flow of water of the buckets, I had copper cables(?) and pails made and in place of the (mud-brick) pedestals (pillars) I set up great posts and crossbeams over the wells. Those palaces, all around the (large) palace, I beautified; to the astonishment of all nations, I raised aloft its head. The “Palace without a Rival” I called its name.

424: 1. At that time, after I had completed the palace in the midst of the city of Nineveh for my royal residence, had filled it with gorgeous furnishings, to the astonishment of all the people . . . .

John Russell in Sennacherib’s Palace Without Rival explains:

A magnificent capital closely identified with the ruling monarch can, however, be a very useful tool for maintaining an empire. Subject peoples visiting the capital would have been greatly awed by the power implied by the sheer bulk and splendor of the monuments of Nineveh, thus reinforcing their inclination to submit rather than to rebeL The construction of the new capital, then, was not a simple matter of royal vanity, but was instead an integral part of Sennacherib’s imperial policy. In the course of his reign, Sennacherib made Nineveh the center of the world . . . .

The key to understanding these images [the palace sculptures] would seem to be not in their subject matter, but rather in their audience and function. The reliefs in the more public areas of Sennacherib’s palace, such as the outer court and throne room, seem to be directed more to outsiders than insiders, and their predominant message is one of warning rather than affirmation. One of their principal functions is apparently to insure the stability of the borders of the empire through the threat of violence expressed in graphic and easily perceptible terms. The ideal of maintaining the flow of tribute from the edges of the empire to its center has not changed, but the reliefs now take a more active part in this process. Rather than presenting visitors to the more public spaces with passive images showing universal submission as a fait accompli, Sennacherib’s reliefs sharply confront them with the consequences of rebellion.

In the more private inner parts of the palace, by contrast, Sennacherib’s reliefs balance these images of conquest at the periphery with images of construction in the center, emphasizing for insiders not only the risks involved in rebellion but the benefits of good government as well. Thus, for audiences both outside and inside the palace circle Sennacherib transformed the role of palace reliefs from affirmations of universal rule into tools to help maintain that rule.

(Russell, 261 f)

Ahab’s Eclipse

I highlighted the words “The ideal of maintaining the flow of tribute from the edges of the empire to its center” because that ideal, Russell explains, had been the theme of Sennacherib’s father who depicted scenes of long lines of tribute bearers in preference to cruel images of the fate of rebels. We are reminded of the ideal utopian scenes of “happy subjects” submitting to Solomon. So much for fleshing out Russell Gmirkin’s citations. Back to his main argument (and one may want to recall the first post in this series for the Ahab context):

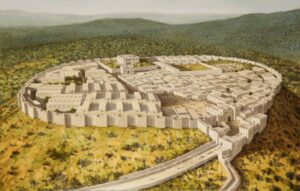

Although the Acts of Solomon credited Shalmaneser III with a building program of ancient monumental architecture that included chariot cities at Gezer, Megiddo and Hazor, and Jerusalem’s temple and palace, these fortresses and impressive buildings of an earlier era are best understood as historically having been constructed by Ahab of Israel. Archaeological evidence pointing to correlations between the temple building account and temple architecture of the tenth to eighth centuries BCE in the southern Levant fully supports the construction of Jerusalem’s temple by Ahab rather than a construction by a local king of Judah (much less Solomon). The attribution of Jerusalem’s temple and other ancient monumental constructions in the southern Levant to the legendary ruler Shalmaneser III (Solomon) was an expression of local patriotic pride among the Mesopotamian (Assyrian and Babylonian) ruling class of Neo-Assyrian Samerina [the Assyrian name for the province dominated by Samaria].

(Gmirkin, 86)

Here Come the Mesopotamians – and They Don’t Mix

According to Gmirkin, then,

— the Assyrian conquerors deported the local elites from the northern kingdom of Israel

— and replaced them with Assyrian and Babylonian officials and colonists who became the “new educated ruling class elites”.

Did not those Mesopotamians eventually lose their identity by merging with the local population? That’s a common view but Gmirkin refers to Mladen Popović’s chapter, “Networks of Scholars: The Transmission of Astronomical and Astrological Learning between Babylonians, Greeks and Jews” who appeals to network theory to dispute the popular notion. When we follow up that chapter we find that Popović presents evidence that the Babylonian elites maintained a strong identity that stood opposed to “popular” culture:

Babylonians and non-Assyrians engaged in royal scholarly networks. The late Assyrian empire had become bilingual and bicultural, with Aramaic becoming the international vernacular. At the same time, there is evidence for adversarial reactions among the Assyrian ruling classes to the rising importance of Aramaic. For example, to a request by the scribe Sin-iddina of Ur to reply in Aramaic, the king answers that the scribe should rather write to him in Akkadian. This example works both ways. On the one hand, it shows that ethno-linguistic boundaries were not strict: letters to the Assyrian king could be written in Aramaic. On the other hand, it demonstrates that such boundaries were not completely ephemeral. The sender of the letter may have asked for too much by requesting the king’s answer also be in Aramaic. The king retorts by raising the boundary and emphasizing its importance: he creates an ethno-linguistic sense of difference between the scribe and himself. While ethno-linguistic and cultural boundaries can be crossed, they are also maintained. However, in the Neo-Assyrian period such boundaries do not seem to have prohibited the accessibility and dissemination of Babylonian science.

If we look at evidence from the Neo- and Late-Babylonian periods, it seems that the Babylonian urban elite had stricter limitations for entry into the scholarly elite than the Assyrians. . . . .

Through cuneiform culture the Babylonian urban elite is said to have expressed a high degree of self-consciousness. For example, a cuneiform text from Hellenistic Uruk shows that the Aramaeans were still considered a separate ethno-linguistic group by some Babylonians; the reference in the late Seleucid list from Uruk of kings and scholars to Esarhaddon’s counsellor Aba-Enlil-dari as the one “whom the Aramaeans call Aḫuqar” shows that the story of Aḫiqar was known but seen as part of “popular” Aramaic culture rather than cuneiform elite culture. The impression gained from cuneiform sources is of Late Babylonia as an imagined community of urban elites who retreated into the imaginary space provided by the temples and the schools, with cuneiform itself being the main distinguishing characteristic of this community. The Babylonian urban elites constructed a cultural identity for themselves, one that became more and more detached from the ethno-linguistic, cultural and political realities of Babylonia in the Hellenistic and Parthian periods. At the same time, evidence from Hellenistic Uruk seems to indicate that they cultivated strong ties with the Greek elite and the Seleucid rulers that ensured their small community thrived. This shows that despite a cultivated identity that seems detached from real life, Babylonian urban elites were also able to relate to changing ethno-linguistic, cultural and political realities and to do so to their own advantage.

(Popović, 170 f)

In the context of Gmirkin’s views, that statement about the Babylonian elites finding common ground with the other elitist Greek arrivals is of interest.

Popović regularly cites “Network Theory and Religious Innovation” by Anna Collar who emphasizes that

most social ties are ‘strong’, reflective of fundamental facets of identity. Social identity can be defined (somewhat simplistically) by group membership.

(Collar, 151)

Hence Gmirkin has justification for his view:

Although Mesopotamians in Samaria eventually adopted the local worship of Yahweh (cf. 2 Kgs 17:24-34), they still remained a strong intellectual and cultural force.

(Gmirkin, 87)

That elitist identity survived into the Persian and Hellenistic eras (also affirmed by Popović above). This is the cultural context for Gmirkin’s thesis that the Pentateuch is a Hellenistic work (link is to the archive of posts related to the book Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible). There are three Babylonian fingerprints on the Pentateuch:

• A significant body of Babylonian traditions set in primordial times (Gen. 1-11).

• Strong traditions about their ancestors originally having lived in Mesopotamia and later having emigrated to the southern Levant. Both Jews and Israelites were autochthonous people of the southern Levant, but the Babylonians resettled in Neo-Assyrian Samerina did in fact come from Chaldea, as Genesis narrates.

• Mesopotamian calendrical and legal traditions, including provisions taken from the Law of Hammurabi and other Old Babylonian and Middle Assyrian law collections (Gmirkin 2017: 144, 175 n. 366).

(Gmirkin, 87)

The Economical Choice?

There is thus no need to invoke Jewish exiles returning from Babylonia to account for pervasive Mesopotamian influences on the Pentateuch, when such influences are more economically and persuasively explained as cultural artifacts preserved by the Babylonian and Assyrian educated elites who still exerted a persistent influence in Hellenistic-era Samaria. These educated Mesopotamian ruling class elites preserved and transmitted the Acts of Solomon down to the Hellenistic era, much as local native Jewish and Samaritan elites of royal descent transmitted the Royal Annals of Judah and Israel.

Thus far I have wondered if I am just a bit thick and need more time to think it all through, but I have not yet seen how the name Solomon came about as a replacement for Shalmaneser or how Shalmaneser’s records entered the Yahwistic narrative. But Gmirkin anticipates my quandary and offers the following points that I have extracted for this post from his final page:

— the authors of Samuel and Kings (writing in the Hellenistic era) had reason to doctor their source documents, the Acts of Solomon, the Royal Annals of Judah and the Royal Annals of Israel.

— those authors relegated the northern kings of Israel (Samaria) as wicked

— given the “scandalous” account in their records of the Jerusalem temple being a cult for Asherah and Baal worship as well as for Yahweh, the authors also assigned later Judean kings as wicked

— the same authors wanted to include an account of the establishment of the Jerusalem temple (and royal palace) but the closest source they had was the Acts of “Solomon” preserved among the Samaritans. They adapted this document to make Solomon the son of David, “the fictional heroic founder of Jerusalem”. (I think Gmirkin here means that David made Jerusalem the main city of Judah since the narrative in Samuel presents David as the conqueror of the city.)

The final Hellenistic-era literary [stratum] of the Acts of Solomon (1 Kgs 3; 4:1-6; 5:1-12; 6:11-13; 8; 9:1-14, 25; 11:1-13, 26-43; 12:1-31) incorporates artificial literary connections between David and Solomon, and between Solomon and the later kings of Judah and Israel. Additional connections were inserted into the earlier novelistic David stories in 2 Samuel, where Shalmaneser III’s conquests in trans-Euphrates were credited to David (2 Sam. 8 and 10; cf. Na’aman 2002: 207-10) and where David was only prevented by God’s prophet Nathan from constructing Jerusalem’s temple and palace as he desired (2 Sam. 7), leaving that task to Solomon. In this new literary tradition, Solomon was transformed from a famous Assyrian ruler and Samaritan hero to a Jewish king at Jerusalem, the son of David and ancestor of the royal house of Judah. The artificial grafting of Solomon into the Jewish tradition between David and Rehoboam had the effect of transferring Neo-Assyrian traditions about Shalmaneser III from c. 850 BCE to c. 970-930 BCE, when Maximalists still seek archaeological evidence for the mythical Jewish kingdom of Solomon.

(Gmirkin, 88)

Once again a brief citation opens up a door to a whole new room for inspection. The Na’aman 2002 reference makes a thorough case for a similar authorial technique by taking another historical figure and turning him into a close-sounding namesake to meet the needs of the fictional story of David:

It seems to me that the figure of Hadadezer ‘ben Rehob, king of Zobah’ was modelled upon the figure of Hazael, king of Aram. The author built up the early, vague figure of Hadadezer along the lines of the better-known king of Damascus. By borrowing outlines from concrete events that had taken place in later times he was able to add a sense of authenticity to the narratives. The selection of Hazael as a model for David’s adversary is not accidental. He was the most powerful and successful king in the history of Aram-Damascus; defeating such a powerful king as Hazael portrays David in the light that suited the historiographical objectives of the author. Whether the name of Hadadezer was ‘borrowed’ from that of the mid ninth-century ruler of Damascus (i.e., Adad-idri) or reflects a genuine memory of David’s tenth-century adversary remains unknown.

(Na’aman, 209)

Na’aman has a similar explanation for the conquest narratives of Joshua but concludes that sometimes the author recycled stories of David’s conquests (also fictional according to a good number of us). One could get dizzy sifting through the layers of and blends of fictional and historical re-writings.

In conclusion

A serious consideration of the Acts of Solomon as an Iron II source thus leads to the complete deconstruction of the notion of a United Monarchy under Jerusalem’s rule, but ironically confirms the existence of Solomon’s kingdom. Solomonic building activities in Jerusalem, however, evaporate under close inspection. It is likely that Jerusalem’s temple and the governor’s house that later served as palace were indeed ninth-century BCE constructions, as broadly confirmed by archaeological evidence, but are best attributed to Ahab, Jerusalem’s ruler at that time.

(Gmirkin, 88)

So thanks for an interesting and thought-provoking thesis, Russell, and thanks to Greg for mentioning the idea to Russell, and thanks to T&T Clark for the review copy, and to those who helped along the way for me to obtain that review copy.

Collar, Anna. 2007. “Network Theory and Religious Innovation.” Mediterranean Historical Review 22 (1): 149–62.

Gmirkin, Russell. 2020. “‘Solomon’ (Shalmaneser III) and the Emergence of Judah as an Independent Kingdom.” In Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity: Essays In Honour of Thomas L. Thompson, edited by Lukasz Niesiolowski-Spanò and Emanuel Pfoh, 76–90. Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies. New York: T&T Clark.

Luckenbill, Daniel David, ed. 1927. Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia. Volume II, Historical Records of Assyria from Sargon to the End. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press.

Na’aman, Nadav. 1994. “The ‘Conquest of Canaan’ in the Book of Joshua and in History.” In From Nomadism to Monarchy. Archaeological and Historical Aspects of Early Israel, edited by Israel Fiinkelstein and Nadav Na’aman, 218–81. Jerusalem: Yad Izhak Ben-Zvi.

———. 2002. “In Search of Reality Behind the Account of David’s Wars with Israel’s Neighbours.” Israel Exploration Journal 52 (2): 200–224.

Popović, Mladen. 2014. “Networks of Scholars: The Transmission of Astronomical and Astrological Learning between Babylonians, Greeks and Jews.” In Ancient Jewish Sciences and the History of Knowledge in Second Temple Literature, edited by Seth L. Sanders and Jonathan Ben-Dov. New York, NY: NYU Press.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!