This post is based on Russell Gmirkin’s chapter, “‘Solomon’ (Shalmaneser III) and the Emergence of Judah as an Independent Kingdom”, in the Thomas L. Thompson festschrift, Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity. All posts addressing the same volume are archived here.

This post is based on Russell Gmirkin’s chapter, “‘Solomon’ (Shalmaneser III) and the Emergence of Judah as an Independent Kingdom”, in the Thomas L. Thompson festschrift, Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity. All posts addressing the same volume are archived here.

Russel Gmirkin’s conclusions (p. 77):

• That the area later known as the kingdom of Judah was under direct rule from Samaria from c. 875 to c. 735 BCE.

• That Yahweh worship was also centered at Samaria during this early period and only appeared at Jerusalem as a result of Samarian regional influences.

• That Judah only emerged as an independent political entity in the time of Tiglath-pileser III under Jehoahaz of Judah in c. 735 BCE.

• That the Acts of Solomon originated in the Neo-Assyrian province of Samaria to celebrate Shalmaneser III as legendary conqueror and founder of an empire south of the Euphrates.

• That old local monumental architecture that the Acts of Solomon attributed to Shalmaneser III, including Jerusalem’s temple, is best understood as reflecting Omride building activities c. 875-850 BCE.

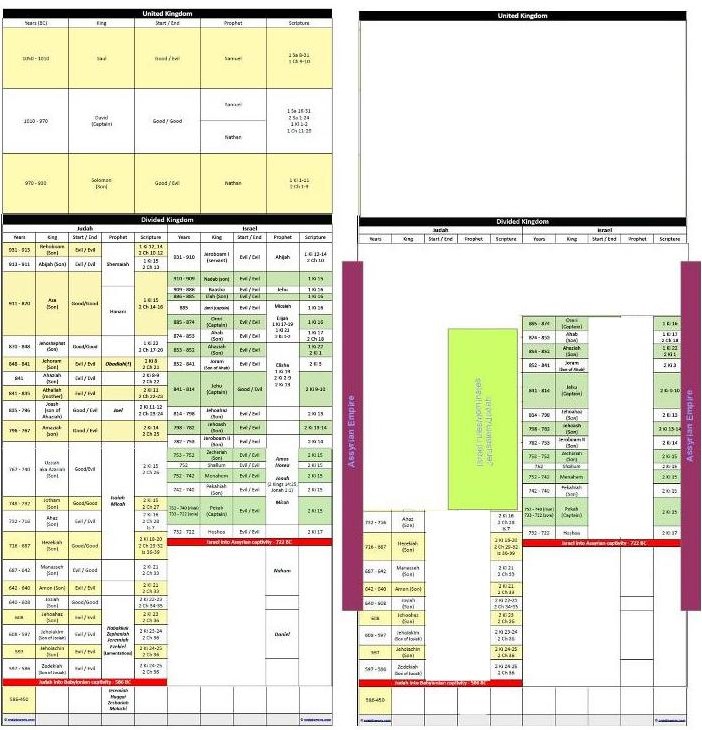

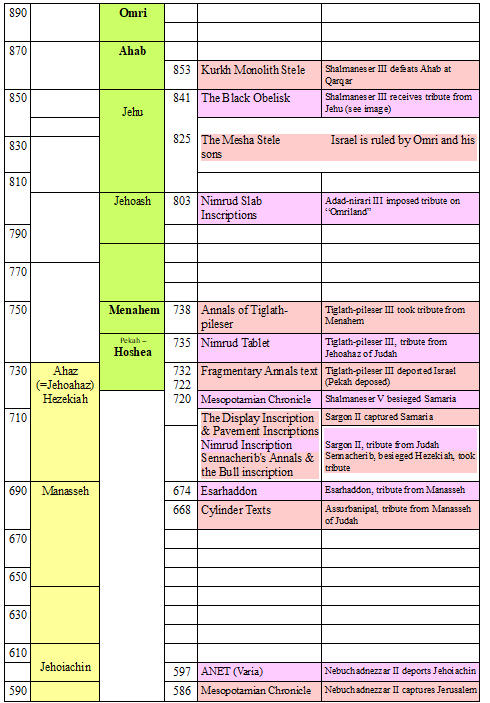

A typical chart illustrating the Old Testament chronology of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah is Jonathan Petersen’s on the BibleGateway Blog. I have copied that chart complete (left). If we use contemporary archaeological sources to determine what the kingdoms of Israel and Judah looked like and make adjustments to that chart we end up with something like the following. The United Kingdom disappears entirely. The Kingdom of Judah only emerges after the Assyrians have hamstrung the Kingdom of Israel in the time of King Menahem in the 730s. Before then the area we think of as the kingdom of Judah had been dominated by the kingdom of Israel.

Russell Gmirkin does not use the above chart but he does seek to reconstruct the historical origins of the kingdom of Judah, its Temple and Yahweh worship by means of the contemporary archaeological sources and comes to much the same conclusion as illustrated on the right side of the above chart. In an effort to get a handle on the archaeological sources and their relation to what we read in the biblical texts I made up my own rough grid based on Gmirkin’s list of archaeological sources. Dates and scale are only approximate. Many of the sources are available online for those interested in that sort of detail.

The kingdom of Judah does not register a mark on the world scene until after the Samaria based kingdom of Israel has been weakened by Assyria and on the brink of final collapse. For earlier Vridar posts on this order of events see

- Jerusalem unearthed – archaeology and Jerusalem 1000 to 700 b.c.e.

- Jerusalem’s rise to power: 2 views (this post compares the views of Israel Finkelstein with those of Thomas L. Thompson)

For those interested in following up the archaeological testimony to the kingdoms of Israel and Judah as per the above chart . . .

Consult Luckenbill’s Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia Volumes 1 and 2 for

- the Kurkh Monolith Stele

- the Black Obelisk

- the Mesha Stele

- the Nimrud Slab Inscriptions (for Adad-nirari III)

- the Annals of Tiglath-pileser

- the Display, Pavement and Nimrud Inscriptions (for Sargon II)

- Sennacherib’s Annals & Bull inscription

- the Cylinder texts (for Ashurbanipal)

Consult Glassner’s Mesopotamian Chronicles (I was able to access this volume on Questia in July last year but cannot see them there now; hope you have better luck) for

- Shalmaneser V’s siege of Samaria

- Nebuchadnezzar II’s destruction of Jerusalem

And Pritchard’s Ancient Near Eastern Texts for

- Esarhaddon’s subjugation of king Manasseh of Judah

- Nebuchadnezzar II’s deportation of king Jehoiachin of Judah

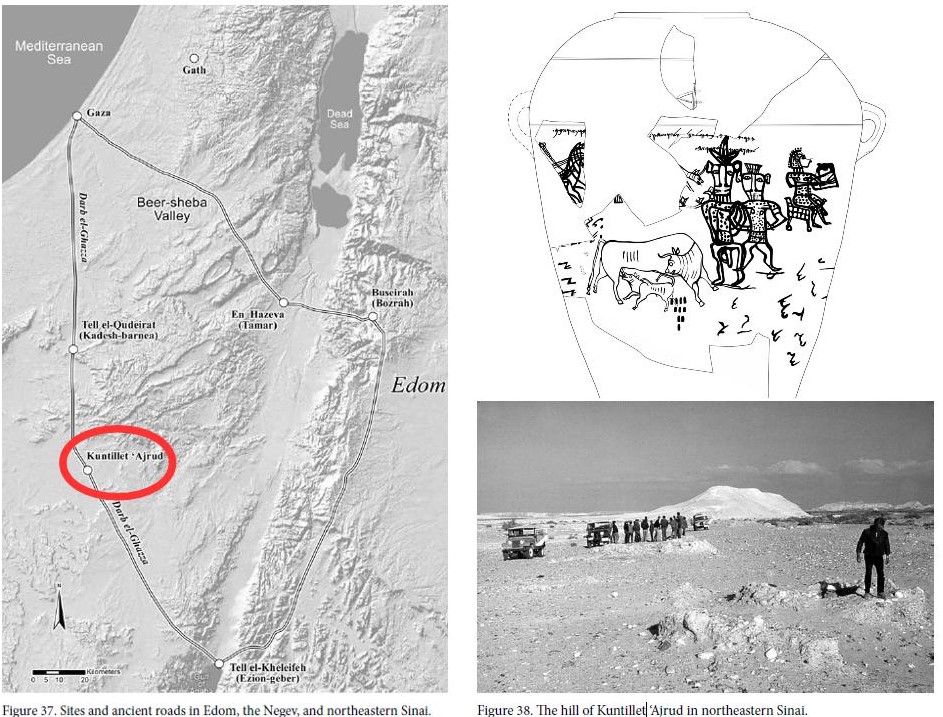

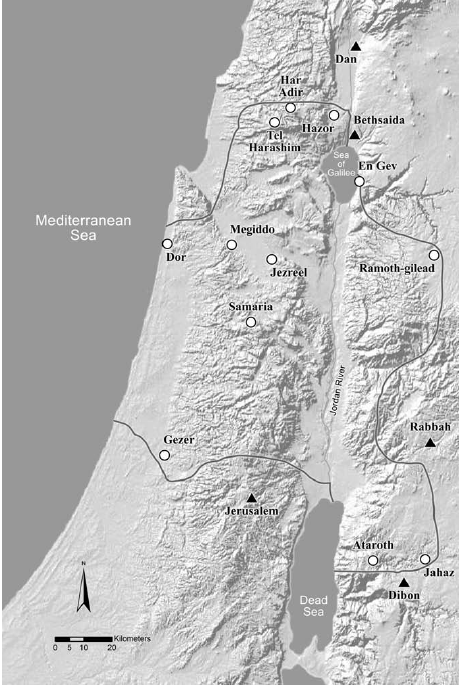

Archaeological finds have demonstrated that Israel under Ahab extended its power from the Galilee through to the Red Sea. The map below is from Israel Finkelstein’s The Forgotten Kingdom : the Archaeology and History of Northern Israel (open access link). Read the concluding paragraphs of chapter 3 for Finkelstein’s discussion of evidence that Jerusalem at the time of Ahab was far from being a significant urban site. The map shows the main sites of Ahab’s building activities.

A key passage in Gmirkin’s article establishing the significance of Ahab’s building activity, including an administrative and temple buildings in Jerusalem (pp. 80f):

An analysis of the inscriptional evidence from c. 850-800 BCE supports the hypothesis that Judah was under direct rule from Samaria during this period. The prominence of Israel under Omri and Ahab as a regional power of the southern Levant has been extensively discussed elsewhere (e.g. Finkelstein 2013: 83-117). In economic and political alliance with the Phoenicians, Ahab’s Israel controlled the coastal route through the (‘Solomonic’) chariot cities of Gezer and Megiddo, the northern inland trade route through Hazor, portions of the King’s Highway from Gilead through northern Moab (Dearman 1989: 159, 169), and the southern trade to the Red Sea (Meshel 2012: 69). The zenith of Omride military power and territorial expansion was during the reign of Ahab (874-853 BCE), whose activities as a builder is attested by monumental architectural remains at Samaria, Jezreel, Megiddo, Gezer, Hazor and elsewhere.

Omride interest in controlling trade routes in both the Transjordan and the Negev in this period calls into question the existence of a kingdom centered at Jerusalem in this period. The geographical territory of Judah was adjacent to the hills of Ephraim and immediately opposite Ammon and Moab. It is difficult to imagine a strong military power such as Israel under Omri and Ahab having overlooked Judah, a relatively easy target whose possession would consolidate Omride control of Ammon and northern Moab as well as giving Samaria full control of the fertile Jericho plain (cf. 1 Kgs 16:34). Omride rule of Jerusalem and Judah would also have given Israel control of the trade route that ran south from Samaria through Judah and the Negev to the Red Sea. Indeed, the royal establishment of the site of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud as a Samarian outpost [see below] indicated to excavator Meshel that Israel must have ruled Judah during the period Kuntillet ‘Ajrud was occupied (Meshel 2012: 69).

The above discussion points to the strong likelihood that Samaria ruled Judah and Jerusalem during the period c. 875-800 BCE. Construction of the Temple Mount’s palace and temple in the ninth century BCE, modeled on the royal compounds on the artificially leveled acropolises at Samaria and Jezreel (Wightman 1993: 29-31; Ussishkin 2003: 535; 2011: 18-21; Finkelstein and Silberman 2006: 105), is best attributed to the Omrides in line with their building activities (Omri at 1 Kgs 16:24, Ahab at 1 Kgs 22:39) well-documented in other cities such as Megiddo, Gezer and Hazor (Finkelstein and Silberman 2006: 163-7, 275-81). Several of these cities had a palace for the governor of the city. Jerusalem in the ninth century BCE is best understood as another such Omride city with governor’s palace and temple (like the temples at nearby ninth-century BCE Tel Motza and eighth-century BCE Arad; cf. Garfinkel and Mumcuoglu 2016: 166-72).

(Finkelstein 2013, Ussishkin 2003, Ussishkin 2011 & Finkelsetin-Silberman 2006 links are to full text open access)

On the Kuntillet ‘Ajrud outpost mentioned above:

The Inscriptions at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud. The archaeological remains at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud on an isolated hilltop in the eastern central Sinai consist of a single layer of occupation (in two phases) dated to c. 820-750 BCE. The inscriptions at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud famously mentioned ‘Yahweh of Teman and his Asherah’ and ‘Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah’ (Meshel 2012: 3.1, 3.6, 3.9, 4.1.1), but omitted Jerusalem and its temple.

(Gmirkin, p. 80)

Given that the Temple Mount’s palace and temple are modelled on the royal compounds of ninth century Samaria as Gmirkin points out, the evidence of “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah” at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud makes a strong case for the Jerusalem temple being instituted for Yahweh worship at the behest of Ahab of Samaria/Israel.

That’s not the way the Bible story tells it, of course. But Gmirkin is only half done at this point. Next post we look at the possible sources for the biblical accomplishments of Solomon.

Gmirkin, Russell. 2020. “‘Solomon’ (Shalmaneser III) and the Emergence of Judah as an Independent Kingdom.” In Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity: Essays In Honour of Thomas L. Thompson, edited by Lukasz Niesiolowski-Spanò and Emanuel Pfoh, 76–90. Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies. New York: T&T Clark.

Petersen, Jonathan. 2017. “Updated: Chart of Israel’s and Judah’s Kings and Prophets.” Bible Gateway Blog (blog). July 17, 2017. https://www.biblegateway.com/blog/2017/07/updated-chart-of-israels-and-judahs-kings-and-prophets/.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I have since updated the post with links to earlier Vridar posts on the archaeological evidence for the kingdom of Judah only emerging as an independent state after the collapse of the northern kingdom of Israel.

Nice article! Love the maps, charts and illustrations.

I noticed that Glassner’s Mesopotamian Chronicles can still be found at ZLibrary.

https://b-ok.cc/s/Glassner%20Mesopotamian%20Chronicles

In light of what comes down to us from the Elephantine Papyri and has been masterfully laid out in the books of Gmirkin and Wajdenbaum here is a simple reconstruction for the Passover festival: https://failedmessiah.typepad.com/failed_messiahcom/2015/04/was-passover-originally-an-ancient-canaanite-ritual-festival-meant-to-stop-the-winter-rain-from-ruining-spring-crops-234.html

And the Wayback Machine yields up the now paywalled 2015 article from Haaretz: https://web.archive.org/web/20150722142128/http://www.haaretz.com/misc/article-print-page/.premium-1.650005?trailingPath=2.169%2C2.208%2C2.210%2C

Mark, I’m a bit bemused by your comment “In light of what … has been masterfully laid out in the books of Gmirkin and Wajdenbaum” in relation to these articles about the Canaanite origins of the original Passover ritual, because I can’t see the slightest connection between the work of these authors and this particular topic.

I’ve not heard of the Mot/Baal theory of the origin of the Passover until now, so it is certainly interesting, but it’s important to point out that the notion of the Passover as an ancient rite, only latterly connected with both the Exodus narrative and the Spring Festival of Unleavened-Bread, has been a standard element of biblical criticism since Wellhausen (in the 1870s), and possibly before.

As regards the Mot/Baal theory itself, my initial caveat would be that it doesn’t seem to offer any explanation of the business of daubing the blood of the lamb on the lintel and doorposts of the house, a manifestly apotropaic procedure, and one that seems to be an essential component of the Passover rite in its most ancient form (at least as available to us from biblical texts).

“doesn’t seem to offer any explanation of the business of daubing the blood of the lamb on the lintel and doorposts of the house, a manifestly apotropaic procedure, and one that seems to be an essential component of the Passover rite in its most ancient form”

Even they in their own time may have had a less than firm grasp on why they did it year after year other than those that came before them always had.

Brings to mind some of the explanations given to all the ethnographers and missionaries who were all over Palestine asking the fellahin questions in forty or fifty years before WW1. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Primitive_Semitic_Religion_Today/WKrWMMWlFAoC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=lintel

Pics of a few dozen maqams here: https://borisfenus.blogspot.com/2013/01/11-lost-shrines.html

Research demonstrates that mosques in the countryside are modern phenomena. Until the end of the nineteenth century, in lieu of mosques, people turned to local patron saints, each of whom had his own maqam, the typical domed single room in the shadow of an ancient carob or oak tree. Each village has its own narrative that describes its holy man, his special grace with God (karamat), his power of intercession (shafa’at), and the miraculous context in which the maqam was built … Holy men, awlia’ Allah, were the centre of religious life at a time when the absolute transcendent other was deemed unreachable. These saints, tabooed by orthodox Islam, mediated between man and the Supreme One.

Saints’ shrines and holy men’s memorial domes dot the Palestinian landscape – an architectural testimony to Christian/Moslem Palestinian religious sensibility and its roots in ancient Semitic religions. The holy site may be a modest square room with a melancholy dome crouching in the shadow of an ancient oak tree perched on the lonely crest of a mountain (as in the villages of Anata, Atara, Halhul, and Yatta), or guarding the entrance of a tiny village or city (as in Husan, Bitunia, Jaffa, or Gaza), or tucked away in the labyrinthine alleys of Jerusalem (Al-Qirami or Sheikh Rihan), or simply a cave next to an ancient oak tree on the site of the rubble of an ancient forgotten abandoned town.

Biblical and Moslem symbols and personages furnished ready-made cross-cultural syncretism: Prophet Jonah (Yunes) in Halhul is both a biblical and Moslem prophet; St. George, known to Moslems as el Khader, provided another symbol. Invariably tombs of companions of the prophet became holy places. Even when names and personages were lacking, the local religious sensibility invoked spirits whose mediation kept humanity in grace with God … El-Qwedrieh is a cave that lies in the rubble of an old abandoned hamlet in the shadow of a huge oak tree outside Halhul. It provides yet another testimony to earlier forms of ancient Semitic religious beliefs masked in the symbolism borrowed from the Judaeo-Christian Moslem tradition. Significantly the big modern mosque of Halhul, El-Sheikh Yunes Mosque, was built so as to encompass the old maqam of el-Sheikh Yunes, which survives as a precious relic preserved within the modern construction.

“People used to pray in the maqam,” Abu Ala’ in Samu’ explained. “We were small in number; the village did not exceed three hundred members, and few men prayed …”

Until the Crimean War neither Moslem nor Christian religious identity was clearly defined. Religion as constitutive of individual identity was relegated to a minor role within Palestinian tribal social structure. Fr. Jean Moretain expressed his surprise concerning Christian/Moslem common practices. Writing in 1848 during the restoration of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, he described his concern that Palestinian Christians could not be distinguished from Moslems. A Christian was “distinguished only by the fact that he belonged to a particular clan. If a certain tribe was Christian, then an individual would be Christian, but without knowledge of what distinguished his faith from that of a Muslim.”

Following the Crimean War, the Latin Patriarchate in Jerusalem was established. Until then the cultural/religious identity of both the Moslem and Christian Arab populations in the countryside remained amorphous. It is difficult to imagine that, until the nineteenth century, orthodox religious life outside the urban centres did not exist.

The Crimean War and its aftermath – the concessions given by the Ottoman Sultanate to its allies, notably France – had a great repercussion on the shaping of contemporary Palestinian religious cultural identity. The modernization of Palestine, the transformation of religion into an element constitutively constituting the individual/collective identity in conformity with orthodox precepts, was a major building block in the political development of Palestinian nationalism. Henceforth it became possible for the state to penetrate, through church and mosque, the Palestinian heartland.

The ones atop hills are probably coterminous with some of the “high places” of ancient times. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/High_Place

“Following the Crimean War, the Latin Patriarchate in Jerusalem was established. Until then the cultural/religious identity of both the Moslem and Christian Arab populations in the countryside remained amorphous. It is difficult to imagine that, until the nineteenth century, orthodox religious life outside the urban centres did not exist.”

“The Crimean War and its aftermath – the concessions given by the Ottoman Sultanate to its allies, notably France – had a great repercussion on the shaping of contemporary Palestinian religious cultural identity. The modernization of Palestine, the transformation of religion into an element constitutively constituting the individual/collective identity in conformity with orthodox precepts, was a major building block in the political development of Palestinian nationalism. Henceforth it became possible for the state to penetrate, through church and mosque, the Palestinian heartland.”

Apparently no one else finds this interesting that as recently as the 1850’s the rural fellahin were still more or less the ‘people of the land’ minding their own business more focused on the local maqam/mukam of the ‘high places’ then on any church or mosque elsewhere. Outside forces changed all of that within a few decades.

Some of the ethnographic accounts from the 1860’s and 1870’s have the caretakers of these various little shrines receiving a foreleg, the cheeks, and the maw of any animal slaughtered there as a sacrifice.

Yes, it’s an interesting record of the Middle East and Palestine under Ottoman rule. The wars of 1948 and 1967 and revolutions of 1973 saw changes in the Middle East that make those days very difficult to imagine now.

https://palestine-family.net/bedouins-and-peasants/ Cut-and-pasted some of the above comment from a 2007 article by a Palestinian ethnographer Ali Qleibo.

He also had another one about the elusive green man Khidr: https://palestine-family.net/el-khader-a-national-palestinian-symbol/ who some say is rooted in the Egyptian Ptah or Ugaritic Kothar-wa Khasis of the Baal Cycle. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El-Khader#Etymology

Mosques were uncommon in Palestinian villages until the late 19th century, but practically every village had at least one maqam which served as sites of worship in the Palestinian folk Islam popular in the countryside over the centuries.

Conder, 1877, pp. 89-90: “In their religious observances and sanctuaries we find, as in their language, the true history of the country. On a basis of polytheistic faith which most probably dates back to pre-Israelite times, we find a growth of the most heterogeneous description: Christian tradition, Moslem history and foreign worship are mingled so as often to be entirely indistinguishable, and the so-called Moslem is found worshipping at shrines consecrated to Jewish, Samaritan, Christian, and often Pagan memories. It is in worship at these shrines that the religion of the peasantry consists. Moslem by profession, they often spend their lives without entering a mosque, and attach more importance to the favour and protection of the village Mukam than to Allah himself, or to Mohammed his prophet… The reverence shown for these sacred spots is unbounded. Every fallen stone from the building, every withered branch of the tree, is carefully preserved. ”

Conder, C.R. (1877). “The Moslem Mukams”. Quarterly Statement – Palestine Exploration Fund. 9 (3): 89–103. doi:10.1179/peq.1877.9.3.89.

We come across remnants of ancient cultural practices in today’s world but unfortunately we cannot assume they are the same, unmodified, practices of ancient times. So many other changes and influences along the way over millennia. One of the most interesting survivals, to me, is that herdsmen on Crete today (from a publication in the 1980s) prove their masculinity through stealing livestock AND “the singing of distichs called mandinadhes.” They sing impromptu rhyming responses to another, keeping on the theme, and hopefully trying for some witty or insulting line. Yet one could scarcely imagine those herdsmen today being the same shepherds Hellenistic poets wrote about as ideal figures, cutely stealing a neighbour’s goat, and also singing bucolic couplets to prove their superiority to one another. Or sometimes to sing love couplets, etc.

RE: “my initial caveat would be that it doesn’t seem to offer any explanation of the business of daubing the blood of the lamb on the lintel and doorposts of the house, a manifestly apotropaic procedure, and one that seems to be an essential component of the Passover rite in its most ancient form (at least as available to us from biblical texts).”

Came across this in https://books.google.com/books?id=s9-utOHPLfEC&pg=PA41&lpg=PA41&dq=hemerobaptists&source=bl&ots=kFD8yQHXUw&sig=ACfU3U3qKQhuMcY_UBohjs2pWMZdoo9t7Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwin84uJ3ufvAhURbs0KHXmvBB84ChDoATADegQIBBAD#v=onepage&q=red%20earth&f=false while looking for an unrelated reference to Hemerobaptists

3:1 Moreover, the tradition of the lamb which was slaughtered in Egypt is still famous among the Egyptians, even the idolaters.

3:2 At the time when the Passover was instituted there—this is the beginning of spring, at the first equinox—all the Egyptians take red earth, though without knowing why, and smear their lambs with it. And they also smear the trees, the fig-trees and the rest, and spread the report that fire once burned up the world on this day. But the fiery-red appearance of the blood is a protection against a calamity of such a magnitude and such nature.

Even in that period twenty to twenty five centuries ago those people may have had little idea why they did certain things other than it had always been done for generations by their forefathers before them.

If in the Levant a bit after the spring equinox one mixed blood with red ochre and daubed it onto walls above outer doorways it would stay there for the better part of a year until being washed away anew when the winter rains again returned. This earliest form of Passover is all about making the sky daddy turn off the rain lest powerful downdrafts from and hail accompanying thunderstorms damages the yet unharvested crops like barley which are then at their most fragile.

You say that Russel seeks “to reconstruct the historical origins of the kingdom of Judah, its Temple and Yahweh worship by means of the contemporary archaeological sources“. And then you quote him as saying:”Construction of the Temple Mount’s palace and temple in the ninth century BCE… is best attributed to the Omrides.”

However the existence of a palace and temple complex in any shape or form in Jerusalem at any time between the 10th and 6th Centuries BCE is based solely on biblical accounts, so surely it shouldn’t enter into the discussion whatsoever, if one is taking a purely archaeological approach.

Sorry, I misspelled Russell’s name. Apologies.

Hi Austendw,

It’s good to call for legitimate evidence for the existence of the First Temple.

I see several lines of evidence that point to a temple at Jerusalem in Iron II.

(1) The flattened acropolis of the Temple Mount is typical of (and an innovation apparently found exclusively in) large scale Samarian royal city construction under Omri/Ahab, found at Jezreel, Samaria, Hazor X, Hirbet el-Mudyine et-Temed (Jahaz) in Omride Moab, and a couple others. The close parallel suggests that the Temple Mount was another Samarian architectural enterprise. I find it extremely unlikely that such a monumental building task as leveling the Temple Mount could have taken place in Persian Era Jerusalem ca. 500 BCE.

(2) The description of the polytheistic temple under Manasseh corresponds to the pictorial and inscriptional finds at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud and arguably derived from the Iron II Annals of the Kings of Judah, an authentic source document embedded within the late (Hellenistic Era) books of 1 and 2 Kings.

(3) The account of the construction of the temple in 1 Kings 5-8 conforms to building accounts in Assyrian inscriptions (and contains remarkable parallels with those associated with Sennacherib’s Palace Without Rival).

(4) The bit hilani form of the temple as described in 1 Kings closely corresponds with Iron II temples up and down the Levantine coast in that period.

Russell Gm.

Hi Russell

I agree that there surely was a temple during the Iron II, but where I’m a little troubled is the notion that an entire monumental palace complex can be ascribed to the 9th Century BCE. The flattened acropolis of the Temple Mount that we see today is of course of Herodian construction, so it tells us nothing about earlier building phases, and the biblical account of the building of the temple and palace is certainly not early or contemporary. And therefore, how can we know that Iron II Jerusalem ever had a wide raised platform comparable in form and date to the one discovered in Samaria? Perhaps there was a less grandiose arrangement of buildings, built in the 8th Century BCE which was “bigged up” in the biblical account, and so having nothing to do with the Omrides? A literary critical analysis of the 1 Kings temple/palace narrative would presumably be relevant to this discussion.

I’m at a disadvantage here, of course, because I haven’t read your article, only Neil’s post, and I know from his outline (and the essay title) that you have a more particular thesis.

One last comment: I thought that “bit-hilani form” refers to the layout of palace architecture (two long rooms with their main axis running parallel with the facade), not the temple plan as described in 1 Kings where the main axis runs perpendicular to the facade.

I’m in the midst of other projects so I can’t drill down into the data right now. Some quick reactions:

Bit hilani architecture has been adduced for both palaces and temples. (What bit hilani specifically referred to is still being discussed.) I find parallels between Assyrian inscriptions and both palace and temple buildign stories in 1 Kgs 5-8. See Hurowitz 1992: 313-16 on the Kings building account based on Assyrian rather than even later Babylonian building accounts, pointing to an early (certainly Iron II) tradition.

Hurowitz, Victor, I Have Built You an Exalted House: Temple Building in the Bible in Light of Mesopotamian and Northwest Semitic Writings (JSOT Supp 115; JSOT/ASOR Monograph Series 5; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1992).

Finkelstein and Ussishkin both believe Jerusalem’s Temple Mount acropolis was leveled off contemporary with the other sites I mentioned above, but allege it was done by a king of Jerusalem in imitation of Samarian practices. I find that interpretation highly doubtful, since (a) there is no inscriptional or other evidence of Judean kings at that time and (b) execution by the king of Israel/Samaria seems the most direct explanation of the distinct common features.

If there was a credible case to be made that (contrary to Finkelstein and others) the leveling of the acropolis was done only at a much later time (e.g. by Herod the Great) I would find that interesting, but I don’t currently have time to research the point. I’ll put a faint question mark by this seeming fact in my brain, however, for future reference.

“The flattened acropolis of the Temple Mount is typical of (and an innovation apparently found exclusively in) large scale Samarian royal city construction under Omri/Ahab, found at Jezreel, Samaria, Hazor X, Hirbet el-Mudyine et-Temed (Jahaz) in Omride Moab, and a couple others.”

With Samarian temples/religion around Shechem was there one Berith or two (El-berith vs. Baal-berith; El of the Covenant vs. Baal of the Covenant)? Pages 180-2 of this pdf copy of the ‘Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible’: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B2gg0n-udc2dN2U2MzhmYTYtZTg4OS00ODBmLWI3NDItNjJkMTllMzlkN2Mz/view?hl=en

“Then they shall take some of the blood and put it on the two doorposts and the lintel of the houses”

Any thought on the origin of this apotropaic practice? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apotropaic_magic

I may be off base, but I suspect that Samarian influence has been downplayed, if not eradicated after the “Return” of those from Babylonian exile. The exiled were the elites of Judaic society and were gone for 50 years or so, so most of the original people were dead. It was mostly their descendants who “returned.” But given permission to rebuild the temple along with their sense of privilege led them to believe they would slide right back into the area and assume leadership positions. However, the Samaritans, who remained behind, did their best to carry on that culture. They were denied the ability to rebuild the temple, sop they build a temple in Samaria instead. They carried on. The “returnees” should have been in disgrace as they caused Yahweh to remove his protection from them during the Babylonian conquest.

But they wanted their privileges, and Samaria was in the way. So they launched a disinformation/propaganda campaign against the Samaritans (for reasons of power, not scripture) and finally a military campaign in which the temple in Samaria was destroyed. (Israelites destroying a temple to Israeli gods, oh my.)

So, later historians were biased against Samaria and we disinclined to grant them any influence they might have possessed.

Much of the Israeli “back story” in the form of written scripture was written/edited at this time to provide a “scriptural guide” for the disinformation campaign.

Steve, recent scholarship (eg: Reinhardt Pummer, Benedikt Hensel) has significantly modified – not to say totally rejected – the Biblical account which suggests that the Judeans (“Israeli” is hardly a helpful term to use of the period) and Samaritans were at each others’ throats from the time of the return of the Babylonian Golah community, as given in the Biblical books of Ezra-Nehemiah. These scholars argue that the tensions between Yehud and Samaria do not date to the Persian period at all, but only developed when the two sanctuary-centres became competitors within the single Hellenistic Coele-Syrian province, where before Yehud and Samaria had been two quite separate, non-competitive and culturally “collaborative” provinces. The fact that the Samaritan and Judean Pentateuchs are very similar (barring obvious tweaks) points to a significant cultural “commonwealth”, and the Elephantine letters similarly portray a cultic co-existence that substantially differs from the anachronistically hostile narrative of the mostly Hellenistic books of Ezra-Nehemiah.

There is always a risk that, in being sceptical of the orthodox biblical narrative, we simply turn it on it’s head – making the biblical baddies (Samaritans) the new goodies (“did their best to carry on that culture”), and the biblical goodies (Judeans) the new baddies (“with their sense of privilege”… “should have been in disgrace”… “they wanted their privileges”… “disinformation campaign”). Happily, scholarship now takes a more balanced view of the period and relationship between Yehud and Samaria.

Thank you for the additional information. Not being a scholar in these things can lead one to conclusions that are not well supported.

Today’s post on Vridar (10-27-20) indicates that “tensions” between Samaria and Judah dated back to at least the Hellenistic era, no? (Excerpts below.)

Recall that we were discussing the geographical extent of the power of King Ahab of Israel: it extended far to the south of Jerusalem. At Kuntillet ‘Ajrud we find an inscription that indicates the existence of a cult centre dedicated to ‘Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah’. Yahweh of Samaria, not Yahweh of Jerusalem. In the same post (and ensuing comments) the likelihood that the Jerusalem temple at the same time was likewise dedicated to ‘Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah’, with priests sent from Samaria to administer the rites. (Vridar, 10-27-20)

The question Gmirkin raises is the whether the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah (or Royal Annals of Judah) described a Jerusalem Temple that was an extension of the cult of Samaria’s Yahweh cult — complete with “asherah” (= Yahweh’s consort). Gmirkin hypothesizes that the Chronicles did exist and that they depicted a Temple cult that was alien to the interests of the Hellenistic-era author(s). Notice above that sources were sometimes cited when the author was addressing a contentious issue. Did the author cite a source in a way that was contrary to its original character in order to “verify” his own theological message?(Vridar, 10-27-20)

The evidence for Jerusalem’s temple as a cultural outpost of Samaria as found in the Royal Annals of Judah scandalized the Hellenistic-era Jewish authors of Kings, who viewed the polytheistic and idolatrous practices in Jerusalem’s temple as having provoked the wrath of Yahweh and caused the fall of Jerusalem. One may discount the accounts of Hezekiah and Josiah as Yahwistic reformers as late, Hellenistic-era literary fictions in which idealized Davidic kings briefly overthrew the apostate religious practices imported there from Samaria.

(Gmirkin, pp. 82 f)

(Souce: same Vridar post as above)

I’m not sure precisely what you are saying, Steve, but the notion that the “Chronicles of the Kings of Judah (or Royal Annals of Judah) described a Jerusalem Temple that was an extension of the cult of Samaria’s Yahweh cult” is completely speculative; those Annals are not extant so their content cannot be known. You assert that we “may discount the accounts of Hezekiah and Josiah as Yahwistic reformers as late, Hellenistic-era literary fictions” but what solid evidence is there for doing that? You run the risk of simply coming up with a scenario and deciding the date of biblical passages solely on the basis of the scenario, which anyone can do with any theory they like, without anything like a control to judge whether its right, wrong, plausible or arbitrary.. which I’m sure we all agree, is not methodologically sound.

Speculative, yes. But “completely” might suggest to some minds that the speculation is without warrant. There are guesses and then there are educated guesses. Enter Bayes, if you like.

The value in such a speculation, for me, is that it leads to an exploration of what we know of similar citations of sources, and that leads us to a new education into Greek historiography and “historical” narratives of Mesopotamian cultures — the main points of which I have attempted to summarize in my most recent post. (There is much more, though, as I alluded to in my comment on one work in my bibliography there.)

We come back to the old adage that the more one learns the more one realizes how much one doesn’t know.

Nihilism is not the appropriate response, I don’t think. Rather, continue to study and compare the sources and ways of piecing them together, always being open to suspicion that our foundations will need further revision along the way, and seeing if small contributions, often in indirect ways, can help clarify one more piece of the picture we are trying to see.

Hi Austen,

If I may reply to the major points you raise:

As my article points out, the passages from the Chronicles of the Kings of Judah contain reliable regnal data starting in the time of Ahaz and Hezekiah, so the content, far from being unknowable, has verification from Assyrian inscriptions and Babylonian sources for the later kings, including Manasseh. Further, the description of Jerusalem’s temple under Manasseh, which arguably derived from this source, broadly corresponds with finds at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, so appears credible based on archaeological control data. I had argued based on archaeological considerations that Jerusalem’s was constructed by Ahab of Israel, so the comparison of Manasseh’s temple to practices under Ahab in Kings represents an independent converging line of evidence.

On the late, Hellenistic Era date of the account of Hezekiah in Kings, 2 Kgs 19.35-37 draws directly on a fragment of the Babyloniaca of Berossus (ca. 280 BCE) quoted at Josephus, Ant. 10.20-21, securing the late, Hellenistic Era date of Kings and specifically of the Hezekiah account.

On Josiah, if I may quote from footnote 7 in my article in the Thompson Festscrift, “The earliest portrayal of the kings of Judah from Manasseh to Zedekiah (the ‘era of Manasseh’) was uniformly negative in the books of Kings, Zephaniah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel. The original negative portrayal of Josiah in 2 Kgs 22-23 was later revised and supplemented with a positive depiction of Josiah as reformer, as I argued in Gmirkin 2011 [“The Deuteronomistic History: a Hellenistic Era Composition in Two Redactions” (SBL Presentation, unpublished, 2011)]. I assigned 2 Kgs 21.1–22.1; 22.3-10, 12-17; 23.26–25.26 to the earlier DtrM or Manasseh redaction, and restricted the later DtrJ or Josiah redaction to 2 Kgs 22.2, 11, 18-20; 23.1-25. As so assigned, DtrJ materials display consistent literary dependence on DtrM, while DtrM shows none on DtrJ, demonstrating the chronological priority of DtrM. It is also apparent that 2 Kgs 22.2 originally contained a negative formula that described Josiah as wicked like his forefathers, a formula also found at 2 Kgs 21.20; 23.32, 37; 24.9, 19.” So there is a solid literary-critical argument that the account of Josiah’s reforms in Kings is late and secondary, certainly no earlier than the fall of Jerusalem’s last king, and arguably much later, based on the demonstrable Hellenistic Era date of Kings.

One can contrast my evidentiary-based approach with those who have claimed, without any evidence whatever, that Kings was written as early as ca. 585 BCE or shortly thereafter, or that there was an earlier redaction of Kings under Josiah (Cross et al), or a yet earlier redaction under Hezekiah (Weippert et al). These latter theories that viewed various redactions of Kings as effectively contemporary with the events narrated can accurately be characterized as speculative. I would disagree with that label being applied to my work, which always seeks to eradicate prior assumptions and to draw careful lines between primary sources, transparent arguments, and conclusions.

Russell Gm.

I must stress that I haven’t read the paper, and only know it via Neil’s sketch and your comments on these pages – and I don’t know the arguments you put forward to support your analysis. But here are my responses to most of the points you raise in the above two comments.

(I) I don’t see that the description of Jerusalem’s temple under Manasseh can be derived from an early annalistic/chronistic source for a number of reasons:

(1) 2 Kings 21:3-8 contains much standard Deuteronomic language. For that reason I can’t see the reference to Ahab (2 Kings 21:3) is a veiled allusion to the builder of the temple but a straightforward Deuteronomistic comparison of wicked Manasseh with wicked Ahab, the arch-villain of the Kings of the Northern Kingdom. That is made even more explicit in 2 Kgs 21:13 (an even later passage) which, rather awkwardly, links the fate of Jerusalem with the fate of Ahab’s dynasty.

(2) 2 Kings 21:3-8 only refers to gods and cultic practices other than Yahwist ones, suggesting that this isn’t a “neutral” list of the cults practiced in the temple (in which case Yahweh of Samaria, or Yahweh of Teman or suchlike could be expected to be included in the cultic roster), but an ideologically loaded list of “sinful” non-Yahwist practices. In particular, verse 6 is a virtual quotation of the practices outlawed in Deut 18:10-11. So this passage, without a doubt, is a later Deuteronomistic passage rather than part of early annals of Menasseh.

(3) The language of 2 Kings 21:3-8 is both Deuteronomistic and generic. Contrast this with 2 Kings 16:10ff where Ahaz gives instruction for a new Assyrian-style (quasi-ziggurat?) altar; both the detail and the fact that it is in innovation (whereas you say that 2 Kings 21:3-8 describes the normative cultic life of the Jerusalem temple from the 9th Century) gives this pericope a far better claim to being from a genuine record of the achievements of the kings of Judah.

(4) While there is a “broad correspondence” with Kuntillet Ajrud finds, I think the correspondence (ie both are polytheistic and the Asherah is mentioned in both) is too broad to draw any major conclusions from, and I fear that you make it a significant link in the chain of your argument. Let’s not forget: we aren’t comparing like with like. 2 Kings 21:3-8 describes a list of the non-Yahwist cultic practices taking place in the temple during the period whereas at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud the deities mentioned were inscribed/written on pithoi, bowls and shards and don’t give a comprehensive summary of an established range of polytheistic cults. They offer contingent evidence of various deities and dedications during the fairly short period of the site’s occupation, roughly during the period 800-760 BCE. So, I think it is rash to use this to make any judgement about which gods were or were not worshipped in Jerusalem itself during the time of Menasseh (c. 695-645 BCE). Yahweh of Teman is one deity named at Kuntillet Ajrud. Was he worshipped in Jerusalem? How can we possibly know? And I’m afraid the same is true of Yahweh of Samaria too.

(II) Your assertion that Hellenistic date of the account of Hezekiah and the entire book of Kings (and perhaps the entire book of Kings 1 & 2) is based (solely?) on the argument that 2 Kings 19.35-37 draws on a quote from Berossus. However, in the standard Loeb edition of Josephus, Ralph Marcus suggests that Ant.10.20-21 isn’t in fact the quote from Berossus, and that the quote has dropped out of the text between Ant.10.19 & 10.20. Though William Whiston in 1737 asserted that the supposed quotation from Berossus proved the veracity of the biblical tale of the plague afflicting the Assyrian troops, there are actually good reasons to agree with Marcus’s assessment:

(1) Had Josephus indicated that the details of the assassination of Sennacherib alone (= 2 Kings 19:37) had been mentioned by Berossus, then that might have been very plausible. However, as the supposed quote includes Ant.10.21 (= 2 Kings 19:35) there is a problem. Literary-critical analysis of chapters 18-19 show that 35 & 37 are from different editorial strata. (see Na’aman “New Light on Hezekiah’s Second Prophetic Story” (https://www.academia.edu/13505698/New_light_on_Hezekiah_s_Second_Prophetic_Story_2_Kings_19_9b_35_Biblica_81_2000_pp_393_402) The ending of the “B1” narrative is determined by the Isaiah’s prophecy of 19:7 (“when he hears a report, he will return to his own country, and there I will have him cut down with the sword”) and this comes to fruition, point for point in vv. 8-9, 36-37. That prophecy includes nothing about the angel killing 185,000 men. And that is because 2 Kings 19:35 is the conclusion of the B2 account, a later supplement (running from 19:9b) that adds a miraculous delivery that B1 knew nothing about. This analysis shows that far from being from one source (Berossus) the passage is from the combined conclusions of two separate biblical strata.

(2) More importantly, it is highly unlikely that Berossus told any story of Sennacherib being routed by Yahweh (as in Kings) or a plague (as in Josephus) or that such a tale would have originated in his Mesopotamian sources. From the Assyrian point of view, the true cause of the end of the Sennacherib’s siege of Jerusalem, was not 2 Kgs 19.37 but 2 Kings 18.15 – in which Sennacherib was apparently just paid off. This is exactly what appeared in genuine Assyrian records, as we know from the Taylor prism etc (see http://www.u.arizona.edu/~afutrell/w%20civ%2008/prism.html). So there is good reason to think that Ant 10:20-21 is just Josephus’s retelling of 2 Kings 19:35-37 and the Berossus quote dropped out of the text. In all probability, Berossus’ comments would have been some general comments regarding with Sennacherib’s campaign in the Levant (perhaps including details of the battle at Eltekeh – confused by both Herodotus and Josephus with Pelusium), included by Josephus to correct Herodotus’ erroneous description of Sennacherib as an “Arabian”.

So, if you are dating the authorship of 1 & 2 Kings to the Hellenistic period on the basis of this piece of evidence alone, I remain unconvinced.

(III) As regards 2 Kings 21-23 – the reigns of Manasseh and Josiah – thanks for giving the prefcise details of the DtrM and DtrJ. I would really love to read the full text of your paper to find out how you arrive at your literary-critical analysis. I confess that I have a couple of problems with it:

(1) It’s not clear to me what evidence there is for thinking that, 2 Kgs 22.2 originally gave a negative judgement of Josiah before DtrJ revised it. Verses 3-10, which you ascribe to the earlier DtrM, gives a rather positive account of Josiah’s actions: he refurbishes the temple of Yahweh, after all, which was surely a good thing from a Yahwistic/Deuteronomic point of view. So what literary evidence justifies the notion that verse 2 originally said Josiah was a bad king?

(2) This may not be a very academic argument but I find it difficult to see that all the rest of the material you attribute to DtrJ could have been written by a single author. You are proposing that this author/editor, confronted with a narrative of bad king Josiah, decided to recast him as the best-ever king, and yet – in the very next breath – commented that he still failed to avert Jerusalem’s fate. He invented a narrative implying that even complete adherence to the law of Moses was useless to counterbalance Manasseh’s wickedness, and that seems to me quite implausible.

I think it makes more sense if we picture an editor confronted with or, one might say, stuck with an account of a good king Josiah (though not necessarily the paragon of perfection of the final edition) who was forced to conclude that Josiah’s pious qualities did not outweigh Manasseh’s impiety.

(3) While I don’t believe that the Josiah account is early or accurate historically – arguably the lion’s share of it is late – I am struck by the unique specificity of some details of 2 Kings 23:7, 11-12, which may have the same sort of claim to being genuine annalistic records as 2 Kings 16:10ff (Ahaz’s altar) mentioned above. Those verses may therefore support a measured argument for a (short-lived?) cultic reform of the Jerusalem temple (ie only the temple cult) during Josiah’s reign, to which much later notions of nation-wide monotheistic reforms were attached.

Hi Austen,

I have time to comment only on one of your points that may be of interest to readers of Vridar. There are many indications that Kings systematically used Berossus as a source on interactions between Israel, Judah, Assyria and Babylonia starting in the time of Tiglath-pileser III that I won’t get into here. The smoking gun is the relation between the fragment of Berossus at Josephus, Ant. 10.20-23 and 2 Kgs 19.35-37. I appreciate your close reading of both.

Let me first point out that this fragment isn’t included in collections by Jacoby (FGrH 680), Müller (FGH), Burstein or Verbrugghe and Wickersham, and is (as you point out) discounted by Marcus in LCL Josephus vol. VI. The reason is simple. There is an obvious relation between this fragment of Berossus (ca. 280 BCE) and the biblical text, and since the text of Kings has conventionally been viewed by consensus opinion as the earlier text, it followed that Berossus must depend on Kings and not vice versa.

Let me make clear, Ant. 10.20-22 does largely follow the biblical text of 2 Kgs 19.35-36 and as such does not reflect an accurate quotation of the Berossan original.

“(20) …But Berosus, who wrote the History of Chaldaea, also mentions King Senacheirimos and tells how he ruled over the Assyrians and how he made an expedition against all Asia and Egypt; he writes as follows: (21) “When Senacheirimos returned to Jerusalem from his war with Egypt, he found there the force under Rapsakēs in danger from a plague, for God had visited a pestilential sickness upon his army, and on the first night of the siege one hundred and eighty-five thousand men had perished with their commanders and officers. (22) By this calamity he was thrown into a state of alarm and terrible anxiety, and, fearing for the entire army, he fled with the rest of his force to his own realm, called the kingdom of Ninos.”

Berossus drew on the Babylonian Chronicles, which elsewhere mentions plagues (“The fifteenth ye[ar]… There was plague in Assyria.” Babylonian Chronicle no. 1, ii.4-5), so it cannot be excluded that Berossus mentioned a plague here, but certainly not in the language that appears in Josephus. Josephus did not read Berossus directly, but likely drew here on Nicolaus of Damascus, who is known to have harmonized Berossus with biblical parallels (see the fragments of Berossus via ND in Ant. Book 1). The hand of ND is also evident in the purple prose of Ant. 10.22 (“By this calamity he was thrown into a state of alarm and terrible anxiety, and, fearing for the entire army…”), typical of ND’s writing style. So Ant. 10.20-22 || 2 Kgs 19.35-36 has intrusive biblical and extraneous material that either derives from Josephus or (as I find most likely) ND.

This is not the case for Ant. 10.22 || 2 Kgs 19.37, which accurately reflects Berossus.

“(23) And, after remaining there a short while, he was treacherously attacked by his elder sons Andromachos and Seleukaros, and so died; and he was laid to rest in his own temple, called Araskē. And these two were driven out by their countrymen for the murder of their father, and went away to Armenia; and the successor to the throne was Asarchoddas, who disregarded the rights of the sons of Senacheirimos next in line.” To such an end was the Assyrian expedition against Jerusalem fated to come.

As Marcus commented (Josephus 6.170 n. b), “According to scripture, Esarhaddon was a son of Sennacherib, but it is not known where Josephus derived his information about the ‘sons of Senacheirimos next in line,’ or even that Adrammelech and Sharezer were the two elder sons.”

The assertion that Sennacherib was assassinated by his “elder” sons, a detail not found in the biblical account, is abundantly corroborated by cuneiform sources. Likewise the disputed succession to the throne after the death of Sennacherib. It is perfectly evident that Ant. 10.23 has details unknown to the biblical authors but known from cuneiform sources. But Berossus is known to have discussed relating to the irregular royal succession, as shown in FGrH 685 F5, which stated that Esarhaddon had the same father but not the same mother as Sennacherib’s assassins. It is thus no mystery where Josephus derived this additional information, as Marcus commented: it derived from Berossus, who Josephus named as source for the passage, and who is known to have had access to various cuneiform sources as well as the Babylonian Chronicle. It follows that Ant. 10.23 is an authentic passage from Berossus, and it is also fully evident that 2 Kgs 19.37 draws on this exact passage. This really renders the date of Kings after the time of Berossus (ca. 280 BCE) as certain.

Fair enough, Russell, I’ll buy the view that the Loeb editor was wrong and the Berossus quotation didn’t drop out of the Josephus text. However, even if this is so, I still can’t accept that this case adds up to the smoking gun you consider it to be.

We can agree that we shouldn’t take Josephus at his word when he suggests he’s quoting from Berossus, since you accept that the wording of Ant. 10.20-22 is derived from 2 Kings. You say it’s possible that Berossus might have mentioned a plague in Jerusalem, (though, to be clear, there is no evidence to support that he did or didn’t), and that you believe Nikolaus of Damascus is responsible for the “purple prose” in this passage. I think Josephus is quite capable of adding drama to a biblical narrative without anyone’s help (cf. his addition of tears in Ant. 4.51 // Numb 16:31), and to creatively elaborate on his source (he introduces Rapsakēs into Ant 10.21, tightening the story and unconsciously merging the B1 and B2 biblical Sennacherib narratives), so I can’t really see evidence of any Berossus in this first passage.

However, your observation that Josephus read Berossus indirectly, via Nikolaus of Damascus, “who is known to have harmonized Berossus with biblical parallels” is crucial to our evaluation of what Berossus actually wrote; and it certainly prevents me from assenting to your confident assertion that “Ant.10.23 is an authentic passage from Berossus.” We don’t have the text of Berossus. So it is actually quite possible that Josephus, in Ant 10.23, is retelling the succinct biblical text of 2 Kings 19:37 – but now supplementing his account with fuller details and a better grasp of the political context – drawn from his reading of Berossus via Nikolaus of Damascus, who may already have gone some way to harmonizing the two sources. What we can say for sure is that, in the language of “CSI”, the traces of genuine Berossus have been “contaminated” by one or both of those writers, and cannot now be recovered with certainty. At the very least, this compromises the probative value of this passage, either way, with regard to the relationship between 2 Kings and Berossus.

So, to sum up my position: since I don’t assume that 2 Kings is post-Berossus, I think there remains a strong possibility that, at a date earlier than you would countenance, the biblical narrative was derived – one way or another – from, say, one of the Assyrian sources that Berossus also drew on. Berossus drew on more such sources for his fuller account (whatever it looked like) and, indirectly, Josephus used that to add a few extra details to his narrative. That seems perfectly reasonable to me. Moreover, the virtue of this scenario is that it gives a plausible account of both (a) the relationship of the biblical text with Berossus’ version of these events, and (b) the literary-critical analysis of the biblical narrative, which shows that 2 Kings 19:35-36 and 2 Kings 19:37 belong to different strata. Your explanation seems to ignore that literary evidence and is certainly incompatible with it.

Oh yes, 2 Kgs 19.37, for comparison:

One day, while he was worshiping in the temple of his god Nisrok, his sons Adrammelek and Sharezer killed him with the sword, and they escaped to the land of Ararat. And Esarhaddon his son succeeded him as king.

Ant. 10.23:

“(23) And, after remaining there a short while, he was treacherously attacked by his elder sons Andromachos and Seleukaros, and so died; and he was laid to rest in his own temple, called Araskē. And these two were driven out by their countrymen for the murder of their father, and went away to Armenia; and the successor to the throne was Asarchoddas, who disregarded the rights of the sons of Senacheirimos next in line.”

Austendw wrote:

“(1) Had Josephus indicated that the details of the assassination of Sennacherib alone (= 2 Kings 19:37) had been mentioned by Berossus, then that might have been very plausible. However, as the supposed quote includes Ant.10.21 (= 2 Kings 19:35) there is a problem. Literary-critical analysis of chapters 18-19 show that 35 & 37 are from different editorial strata. (see Na’aman “New Light on Hezekiah’s Second Prophetic Story”…) The ending of the “B1” narrative is determined by the Isaiah’s prophecy of 19:7 (“when he hears a report, he will return to his own country, and there I will have him cut down with the sword”) and this comes to fruition, point for point in vv. 8-9, 36-37. That prophecy includes nothing about the angel killing 185,000 men. And that is because 2 Kings 19:35 is the conclusion of the B2 account, a later supplement (running from 19:9b) that adds a miraculous delivery that B1 knew nothing about. This analysis shows that far from being from one source (Berossus) the passage is from the combined conclusions of two separate biblical strata.”

Hi Austen. Let me just state that I do not find the division of 2 Kgs 18-19 into distinct editorial strata B1 and B2 compelling. 2 Kgs 19.7 foreshadows the whole of 2 Kgs 19.35-37 (which in turn derives from Berossus). You abridge the quotation of 2 Kgs 19.7, which reads in full, “Behold, I will send a blast [ruach = wind or spirit] upon him, and he shall hear a rumour, and shall return to his own land; and I will cause him to fall by the sword in his own land.” 2 Kgs 19.7b is connected to 19.36-37, yes, but 19.7a is equally connected to 19.35. Various Hebrew Bible passages depict spirits as angels (e.g. 2 Chr. 18.20) or equate the two (Ps. 104.4). The wind or spirit sent by God against him has its proper parallel to the angel of God who smites the war camp of the Assyrians (perhaps by plague) in 19.35 but has no parallel in 19.36-37, contra Na’aman, Childs, et al.

Furthermore, there is evidence that the entirety of Ant. 10.20-23 derives from Berossus, both Ant. 10.20-22 (which contains some language harmonizing with the biblical account of 2 Kgs 19.35) and 10.23 (which faithfully reflects the original text in Berossus and underlies 2 Kgs 19.36-37). Ant. 10.20-21 begins,

“(20) Berosus, who wrote the History of Chaldaea, also mentions King Senacheirimos and tells how he ruled over the Assyrians and how he made an expedition against all Asia and Egypt; he writes as follows: (21) “When Senacheirimos returned to Jerusalem from his war with Egypt When Senacheirimos returned to Jerusalem from his war with Egypt…”

Although Sennacherib never campaigned in Egypt, both Herodotus and Berossus claimed that he did. This points to Ant. 10.20-21, which you want to detach from Berossus, to an extra-biblical and authentically Berossan tradition. (Compare also the later clearly Berossan coloring of the alleged conquest of parts of Egypt by Nebuchanezzar in both Jeremiah and Ezekiel.)

If we consider Ant. 10.23, one is first struck by its intimate familiarity of the circumstances surrounding Sennacherib’s death and his succession by his younger son Esarhaddon. It does not read as an expansion of the text of 2 Kgs 19.36-37, but is concise and of consistent style and appears to closely reflect the Berossan original, while 2 Kgs 19.36-37 reads like a simple abridgment. Importantly, one has to question how the authors of Kings knew about these details of events in distant Nineveh:

“(36) So Sennacherib king of Assyria departed, and went and returned, and dwelt at Nineveh. (37) And it came to pass, as he was worshipping in the house of Nisroch his god, that Adrammelech and Sharezer his sons smote him with the sword: and they escaped into the land of Armenia. And Esarhaddon his son reigned in his stead.”

The withdrawal of Sennacherib to Assyria in 701 BCE could have been known to contemporary Jews or even inferred by later Jews who read Herodotus. But the assassination of Sennacherib in a temple (confirmed by a text under Assurbanipal) in 681 BCE, and the subsequent civil war and flight of the elder sons Urartu (to the city of Bushshua, and subsequently to Shupria, which Esarhaddon conquered and punished in his eighth year for harboring the fugitives)—these obscure details are all known from Assyrian inscriptions, but the notion that the authors of 2 Kgs 19.37 had independent knowledge of these developments borders on the absurd. These minutae were known in Assyria, documented in cuneiform sources, and reflected in Berossus, but it is special pleading to imagine these distant events were known in Judea. Rather, they derived from Berossus, which formed the historical core of the essentially midrashic narrative of Sennacherib’s siege in 2 Kgs 18-19.

Thompson understood the “myth of return from exile” to have originated with the propaganda of Persians who deported a new population to Palestine, as was a custom with ancient empires. (Whether the deportees included descendants of original inhabitants we cannot know). He cites at least one instance of those being deported being led to understand that they were the original inhabitants of a land returning to reestablish the rightful gods.

Gmirkin views the “returnees” as descendants of the Mesopotamians sent by Assyrians and then the Babylonians to administer the lands, if I understand/recollect correctly.

Philip Davies pointed out that whoever the new settlers were they likely looked down on the local inhabitants and eventually classified them as undesirable “Canaanites”.

No, my position is that the historical community of Babylonians and other Assyrians who were placed in the Assyrian province of Samerina in the later 700s BCE to replace the deported Israelite ruling class largely retained their identity and traditions and persisted in Samaria down to the Hellenistic Era (cf. Jewish polemics at 2 Kgs 17.24-41), where they influenced the creation of the Pentateuch and other biblical writings, as evidenced by: Mesopotamian origin traditions in Genesis, Mesopotamian calendar names, a sprinkling of Old Babylonian and Middle Assyrian Pentateuchal laws, among others, as I alluded to in Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible as well as in the conclusion of the article Neil is writing about.

This is a distinct issue from whether there could have been a return of Judean Babylonian exiles to Jerusalem as in the late Ezra novella. In my article for the Thompson Festschrift I merely observe that Mesopotamian traditions in the bible arguably originated with actual Mesopotamians educated elites living in Samaria, not Judean returnees from a brief period of exile in Babylon, to whom scholarship has traditionally attributed all biblical traditions Babylonian. Samaritan authors of actual Babylonian ancestry made significant contributions to biblical writings.

I meant that the Babylonian and Assyrian communities were placed in Palestine as ruling elites as you explain: — my “returnees” in quotes was intended to indicate that they were not in any sense literal returnees, only that their presence has been in later myth been interpreted as such, their actual origins being lost (pre-RG?!)

Is that correct or am I still missing something?

I don’t think the Babylonian and Assyrian residents in Neo-Assyrian Samaria (Samerina) were ever considered returnees to the land. They did not dwell in Judah (where there may have been some historical returnees, notably the “Davidic” royal line of Judah [e.g. Zerubbabel]), but only in the north in Samaria. Although Deuteronomy appears to have foreseen a return of the Samarian captivity, this did not play out in later biblical literature like Kings, the Prophets, or Ezra-Nehemiah. As a result of the so-called Samaritan schism, the Jerusalem-based authors of the later portions of the Hebrew Bible preferred to think of the Samarian exile as lost (the later so-called lost 10 tribes), and the Samaritans as Yahwistic Babylonians (2 Kings 17), but not as returnees. I find evidence to support a substantial Assyrian-Babylonian component in Persian and Hellenistic Era Samaritan intellectual traditions, but I don’t link it to an alleged return to Samaria. Meanwhile, I find little or no Mesopotamian biblical traditions that can be traced to the returnees to Judah, but instead trace these to Samaritans of Babylonian ancestry. I need one of your famous charts to illustrate all this, but I hope this wordy explanation will suffice.

The Babylonian residents also dwelt only in the north in Samaria?

Yes, Babylonian educated elites were brought in to replace deported Samarian elites after the conquest of Samaria in 725 BCE by Shalmaneser V and in 723 BCE by Sargon II. Assyrian inscriptions claimed a total of 27,280 or 27,290 Samarians were deported to Mesopotamia by Sargon II in the years 716-708 BCE (Becking 1992:25-32; Levin 220). These will have included the ruling class, the educated elites, craftsmen, and soldiers.Assyrian documents record the subsequent use of Samarian charioteers in the Assyrian army. The kingdom of Samaria was converted into an Assyrian province named Samerina. In 715 BCE, Sargon deported a body of Arabians to Samaria (LAR II, §17). In addition, the province of Samerina received a substantial influx of deportees from Babylon, Cuthah, Ava, Hamath and Sepharvaim, most likely in the aftermath of the defeat of Merodach-Baladan in 710-709 BCE by Sargon II. Such population exchanges were common in the aftermath of rebellion and conquest in the Neo-Assyrian period. The existence of a new expatriated population from Mesopotamia in eastern Samaria at this time is corroborated by archaeological findings, which include new houses constructed in Mesopotamian architectural style, cuneiform texts, and pottery with wedge decorations (Zertal 1989; 2003).

After the fall of Jerusalem to Nebuchadnezzar there was a deportation of educated elites from Judah into exile, but no similar population transfer of a foreign population (Babylonian or otherwise) to Judah. Later there may have been a return of some exiled Judeans to their native land, including the royal house. But there is no evidence of an ethnic Babylonian population living in Judah, only in Samaria.

There is so much I did not (and still do not) know which makes it very hard to make sense of many of the things I have read … . It looks as if I would have had to become an historian to understand even a tiny fraction of what was going on in this area.

Thanks for helping to educate me.

It does not help that among “minimalists” there are different scenarios being proposed to take the place of the orthodox biblical narrative. One day I should do a new series on the different views of some of the scholars.

Is the main confusion to do with place of the Samaritans?

“The people of the land” were still frequenting their “high places” (bemah) hardly more than a century ago. page 147: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Primitive_Semitic_Religion_Today/WKrWMMWlFAoC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=deuteronomist On page 145: When we asked them afterwards why they did not look towards the south, toward Mecca, the Moslem Kibla, they said, that, as there prayer was directed to the “God of the place,” it was a matter of difference what point of the compass they faced.

According to Claude Reignier Conder’s description in 1877, the Palestinian locals attached “more importance to the favour and protection of the village Mukam than to Allah himself, or to Mohammed his prophet”.

“It is in worship at these shrines that the religion of the peasantry consists. Moslem by profession, they often spend their lives without entering a mosque, and attach more importance to the favour and protection of the village Мukam than to Allah himself, or to Mohammed his prophet.”

As a rule, maqams were built on the top of the hills or at the crossroads, and besides their main function — shrine and prayer place, they also served as a guard point and a guiding landmark for travelers and caravans. Over the years, new burial places appeared near maqams; it was considered as honour to be buried next to a saint. Big cemeteries formed around many Muslim sanctuaries.

Almost every village in Palestine has a wali, a patron saint, whom people, predominantly rural peasants, would call upon for help at his or her associated sanctuary.

“There is, however, in nearly every village, a small whitewashed building with a low dome — the “mukam,” or “place,” sacred to the eyes of the peasants. In almost every landscape such a landmark gleams from the top of some hill, just as, doubtless, something of the same kind did in the old Canaanite ages.”

Conder, 1877, p. 89: “…the local sanctuaries scattered over the country, a study which is also of no little importance in relation to the ancient topography of Palestine, as is shown by the various sites which have been recovered by means of the tradition of sacred tombs preserved after the name of the site itself had been lost.”

Conder, 1877, pp. 89-90: “In their religious observances and sanctuaries we find, as in their language, the true history of the country. On a basis of polytheistic faith which most probably dates back to pre-Israelite times, we find a growth of the most heterogeneous description: Christian tradition, Moslem history and foreign worship are mingled so as often to be entirely indistinguishable, and the so-called Moslem is found worshipping at shrines consecrated to Jewish, Samaritan, Christian, and often Pagan memories. It is in worship at these shrines that the religion of the peasantry consists. Moslem by profession, they often spend their lives without entering a mosque, and attach more importance to the favour and protection of the village Mukam than to Allah himself, or to Mohammed his prophet… The reverence shown for these sacred spots is unbounded. Every fallen stone from the building, every withered branch of the tree, is carefully preserved. “

I broadly agree with this and your later post in this thread, Russell … but I have a few questions:

(1) How precisely can you trace Babylonian traditions in the later portions of the Hebrew Bible to the Babylonian deportees to Samaria, as opposed to Babylonian returnees to Yehud? How would you distinguish the two?

(2) Doesn’t this influx of Babylonian and Assyrian elites into Samaria in the 7th Century open the possibility that it was these people who brought many of the Mesopotamian literary motifs, traditions and narratives (the ones that you believe must have been derived from Berossus) into the Primal History of Genesis 1-11?

(3) You say that “the historical community of Babylonians and other Assyrians who were placed in the Assyrian province of Samerina in the later 700s BCE … largely retained their identity and traditions and persisted in Samaria down to the Hellenistic Era”. In their 2000 essay Assyrian Deportations to the Province of Samerina in the Light of Two Cuneiform Tablets from Tel Hadid, Na’aman & Zadok discuss the archaeological evidence indicating “that the deportees preserved certain characteristics of their former identity for (at least) half a century” but what evidence is there that these deportees retained that identity, distinct from the native Samaritans, all the way down to the Hellenistic period? Josephus comments that the Samaritans were called Cutheans by the Judeans, but that’s apparently a derogatory term meant to impugn their authenticity as Israelites rather than a name the Samaritans called themselves (Ant 9.290). Isn’t it more likely that the Babylonians eventually assimilated into the native population, and that their Mesopotamian traditions were incorporated into Samaritan traditions?

These are all valid and important questions, to which I have already given considerable thought over the past couple years and have answers backed by considerable research and analysis. I hope to respond at some point, but unfortunately my reply would be of article or at least blog posting length. A peer-reviewed journal article would be ideal, but I have other pressing projects already in the queue. Let me consider how and when I can get back to you (and Vridar) on this subject.

I haven’t replied sooner because I’ve (unsuccessfully) been trying to find my copy of Thompson’s “The Mythic Past”, a book that had no notes and no references (we have actually discussed this very point before). So when Thompson gave an “instance of those being deported being led to understand that they were the original inhabitants of a land returning to reestablish the rightful gods,” it’s impossible to verify if that case was an apt analogy, if the context and circumstances were similar, and if significant conclusions can properly be drawn from it about Yehud etc etc. And that makes it, for scholarly purposes, all but valueless.

I have attempted to present as fairly as possible a variety of scenarios on this blog. A good number of them are alternatives to Thompson’s reconstructions. I do not dogmatically argue for any one of them. Each of them has outstanding questions and room for adjustment.

My understanding is that the various views of Thompson, Davies, Lemche, are presented as hypotheses that are alternatives to the traditional views. The views are debatable and open to revision — they each are different from one another, after all. The reason they offer them as superior alternative scenarios to the orthodox views is because they cohere more closely to the known evidence than the hitherto conventional wisdom.

If any of the hypotheses cannot be proven beyond doubt it does not automatically follow that they are without value or mere empty speculation. We are attempting to see what scenarios come closest to fitting the contours of the known evidence. Right now we have alternative “minimalist” scenarios, thus demonstrating that none is watertight but at the same time that each has a rationale that is lacking in the conventional scenarios.

The fundamental methods of historical-critical inquiry of the “minimalists” (or, in Gmirkin’s case, a “post-maximalist”) are sound. Their reconstructions for alternative scenarios, though, have gaps, fuzzy edges, hanging questions relating to this or that piece of evidence. If it were not so then we would have all the answers and can finally close shop.

Neil, I wasn’t saying that all “minimalist” arguments were without value… I don’t believe that at all and have never said any such thing. I think you are becoming a little over-defensive.

I was talking about the very specific unreferenced case that Thompson gave, which you referred to in your post. I think it’s entirely justified to argue that, for the purposes of scholarly discussion, that specific point was rendered pretty useless because it was unreferenced, meaning that we mortals couldn’t verify or evaluate it. For all I know it may in fact be a very potent piece of evidence, but until it’s referenced properly, it’s like the Delphic oracle.. impossible to interpret reliably. Perhaps now we can since we could search the internet to find literature about that example that would throw some light on it.

I would argue with you about whether the “fundamental methods of historical-critical inquiry of the “minimalists” … are sound”, at least in one area. I particularly cannot accept what appears to be their total refusal to countenance any diachronic analysis of the biblical texts whatsoever. They – including Gmirkin – have simply junked all scholarship in this area in favour of a very simple insistance on a synchronic biblical text. Evidence of continuing editorial activity, redaction and supplementation is either rejected or, more often simply ignored. I think this flies in the face of the evidence, is methodological madness and inevitably produces skewed answers. (The hailstone case of Joshua 10 in todays post – 26.X.2020 – is a case in point). That’s why I certainly cannot accept Gmirkin’s Hellenistic hypothesis (or even get my head around some aspects of it).

You say “we have alternative ‘minimalist’ scenarios, thus demonstrating that none is watertight but at the same time that each has a rationale that is lacking in the conventional scenarios” and I’d really love to know which scenarios count for you as a minimalist with a rationale, and which count as a “conventional” or “traditional” and without a rationale. I ask because we may be undertanding the term minimalist differently and so may be talking past each other. I mean, for William Dever, Israel Finkelstein is a minimalist; for Thomas Thompson, I think Israel Finkelstein is a maximalist. So where do you draw the line between the two camps? And I also ask because I am wondering which camp I am in? I am certainly happier with approaches that accepts nuanced, detailed, diachronic analysis of the biblical texts – so by that standard I must be “traditional”. I certainly think that the texts must therefore have a longer editorial history than the simple synchronic analyses of the Copenhagen school (however they vary) or the Pan-Hellenistic group (Wessalius, Wajdebaum, Gmirkin) admit. But that doesn’t mean I accept the “traditional” 19th Century chronologies or historical scenarios. I am increasingly interested in the Samaritan Pentateuch’s close similarity with the Massoretic Pentateuch, and what that implies for the formation of the biblical narrative and its chronology, which I suspect is quite outside the comfort zone of the so-called “traditional” scenarios. That puts me somewhere in the indeterminate middle, I guess…

Anyway, this is a ramble, it’s late in London, and I’m going to bed now. And frankly, I hate the internet, because somehow it inevitably raises the temperature, turns discussion into battle, and makes enemies of us all.

What I think I was saying was without value was the rejection of any hypothesis that cannot be proven without doubt. If I misunderstood or overstated your point as it appears I was (I was attempting to address several comments, I think) in this case then I was indeed talking past you and apologize. (And yes, there is much that is frustrating in Thompson’s writing: sometimes he seems to me to write at an ethereal conceptual level and assumes too often that readers will know enough for him not to bother with complete citations. But he does make me ask new questions — and sometimes sends me on long searches to see for myself the evidence he is discussing.)

Hypothesis A interprets certain words as signs of continuing/diachronic editorial activity; Hypothesis B interprets those same words as the result of an author using different sources. (Paraphrasing a footnote by Stott commenting on a point by Na’aman, p.53). I suppose it’s possible for each side to despair that the other is simply ignoring their interpretation of the evidence. We look for the arguments and criticisms on both sides. (We are speaking generally, of course, since I don’t know any hypothesis that imposes a blanket denial of all redactional activity.)