Updated 9.00 am (UTC+8) 27th August 09

The biblical legend:

1000 to 700 b.c.e. covers the biblical time from the reign of Solomon to the fall of Jerusalem’s neighbouring northern kingdom of Samaria. According to the narrative of 1 and 2 Kings Jerusalem in the early part of this period was

- the administrative capital of a kingdom of fabulous, even legendary, wealth;

- after the breakup of this kingdom Jerusalem remained the centre of the southern Kingdom of Judah and power base of the descendants of David and Solomon.

- a base from which kings amassed armies of hundreds of thousands;

- the centre of an empire “from the Euphrates to the border of Egypt” and influential alliances were made with neighbouring kingdoms and wars waged.

This Jerusalem-led kingdom of Judah was said to be an ethnically cohesive society tracing its ancestors back to three sons of Jacob – Judah, Benjamin and Simeon.

And of course Jerusalem retained throughout this period the capital to support and maintain epic royal buildings and the famous Temple. Even when Egyptian invaders plundered the temple and royal treasury, the king of Jerusalem still had the resources to replace the losses with other metal, especially bronze.

The down to earth reality:

Archaeologists have uncovered a very different Jerusalem throughout this period. The following outline of the status of Jerusalem throughout most of the first three hundred years of the first millennium is taken from the archaeological findings extensively surveyed by Thomas L. Thompson in Early History of the Israelite People : from the Written & Archaeological Sources.

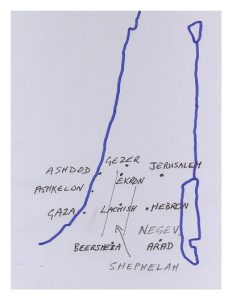

Mudmap is mine, not Thompson’s, of course.

Correction: EKRON should not be indicated as part of the Shephelah

Relative size of Jerusalem

Jerusalem was “a small provincial town at best.” “[I]t was not a very large town, and was by no stretch of the imagination yet a city.” (p.332)

It was comparable in size to Lachish and Gezer.

Geographic location of Jerusalem

Jerusalem was isolated from other comparable urban areas in the Negev to the south and the Shephelah area (Lachish and Gezer) east and south-east and, given its size, very unlikely to have had the resource base to have exercised any controlling influence over them.

“Its relative isolation protected its independence in a period absent of any great political power in Palestine. This same isolation restricted its power and political influence largely to its own region, and the small subregions contiguous to it. The limited excavations in Jerusalem confirm the picture of a small provincial commercial center, substantially removedi from the international trade routes and their centers of power.” (p.332 — citing Jamieson-Drake)

Jerusalem did have easy access, however, to the small settlements in the hills area immediately south (the northern part of the Negev).

Hill settlements and forts

The hill area south of Jerusalem was a target of commercial rivalry among Jerusalem, Hebron and cities in the east such as Lachish.

Centres like Hebron were responsible for constructing strings of forts in the south. These appear to have been constructed as part of attempts to increase security for the growing olive oil industry in particular by putting an end to nomadic or seasonal pastoral incursions into the Judean hill and Negev areas. The forts can be interpreted as evidence of an attempt to protect scarce agricultural resources from irregular pastoralists. As these nomadic groups were forced to settle the populations of the hill areas — and numbers of villages here — grew. So did exploitation of the hill areas timber, pastoral and horticultural resources.

Commercial relations of Jerusalem

The hill area south of Jerusalem was dotted with smaller villages that sprang up in response to pastoral and horticultural activity. This hill area, with its timber, pastoral and crop resources, relied on larger towns to the south, such as Hebron, and those to the east, like Lachish, and Jerusalem in the north, to sell their produce. These larger towns can be presumed to have been in commercial rivalry for the resources of the hill areas — especially olive oil, but also timber, pastoral and horticultural products.

Olive producing villagers in the hill area could bypass Jerusalem and trade directly with Ekron and Lachish, and of course Hebron — which was a major source of the commercial rivalry among centres like Jerusalem, Lachish and Hebron.

There is no reason to believe that Jerusalem had the means to dominate any but the closest villages in the hills and Negev to her south. These were more likely dominated by Jerusalem’s competitors like Hebron and the Shephelah towns of Lachish and Ekron.

Jerusalem ignored by the surrounding evidence

A letter from Arad indicates that Arad was politically independent from Jerusalem.

A text from Kuntillet Ajrud refers to Yahweh of Samaria and Yahweh of Teman, but there are no references to a Yahweh of Jerusalem.

Pharaoh Shoshenk (biblical Shishak) plundered towns in southern Palestine, including the Ayyalon valley adjacent to Jerusalem, but makes no reference to Jerusalem among the town he cited to boast his victories.

Comparing Judea with other regions, and Jerusalem with Samaria

Especially in the ninth century b.c.e. “the primary agricultural regions of greater Palestine developed significantly centralized regional forms of government (e.g. Phoenicia, Philistia, Israel, [Syria], Ammon . . . ) and . . . Arab controlled overland trade began to make a major economic impact in the emerging capitals of these states.” (p.290)

This was not the case in the Judean area — the Shephelah and Negev and hill regions around Jerusalem. Here each city, like an independent city-state, vied for commercial-imperial type dominance in the surrounding areas, as outlined in the note on commercial relations above. [T]he political development of Jerusalem as a regional state, controlling the Judaean highlands, lagged substantially behind the consolidation of the central highlands further north.” Samaria, for example, established complex regional associations, making itself the capital city of the entire region. The power base in Jerusalem never extended politically beyond Jerusalem itself.

Dramatic changes to Jerusalem from around 700 b.c.e.

721 b.ce. Assyria destroyed Samaria and the northern kingdom of Israel came to an end.

701 b.c.e Assyria moved further south and destroyed Lachish, a leading commercial rival of Jerusalem. Assyria further took charge of the coastal trade that had been based around the oil-processing centre of Ekron.

It is from this time that the population of Jerusalem begins to multiply. From the time of these two events, especially the destruction of Lachish, that “Jerusalem begins to take on both the size and character of a regional capital.” Citing Jamieson-Drake and E. A. Knauf, Thompson adds:

The radically altered political creation in greater Palestine, and the need to absorb a considerable influx of refugees to its population transformed Jerusalem from a small provincial, agriculturally based regional state . . . into a stratified society, with a dominant elite (and perhaps a temple supporting a state cult), in the form of a buffer state lying between two major imperial powers: Egypt to the South and Assyria to the North. These changes, and the radical alteration of the political map of Palestine, brought — at least for Jerusalem’s new elite — considerable growth in wealth and prestige . . . . (pp.333-334)

The rise triggers the fall

Thompson continues:

This growth in wealth and prosperity of its elite, as Jerusalem became increasingly involved in the international politics of trade, ultimately led Jerusalem into direct confrontation with the Assyrian army and its final destruction and dismemberment by the Babylonians. . . . The devastation [by the Assyrians and Babylonians] itself brought to southern Palestine a physical impoverishment and economic depression that ravaged the region. Assyrian and Babylonian military and political policies of administration systematically destroyed the region’s infrastructure and brought about the collapse of the entire society. (p. 334)

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I am thinking that material like this should be in a wiki, publicly available but edited by a few collaborators. What do you think? A sort of collection of what we think we know and current questions.

NotesProf @ gmail.com

Maybe. Thinking about it. Thanks for the thought. Will let you know. I used to be much more active on other discussion lists and boards, and I see that some of my posts become a discussion point on other blogs or wikis. The original intent of this blog was nothing more than to put down in writing some of the things I enjoyed reading and thinking about and sharing them with whoever might find them of interest too.

I would be happy to provide the wiki.