2019-05-12

An Interesting Perspective

Musings on biblical studies, politics, religion, ethics, human nature, tidbits from science

In historical research, we evaluate the plausibility of hypotheses that aim to explain the occurrence of a specific event. The explanations we develop for this purpose have to be considered in light of the historical evidence that is available to us. Data functions as evidence that supports or contradicts a hypothesis in two different ways, corresponding to two different questions that need to be answered with regard to a hypothesis:

1. How well does the event fit into the explanation given for its occurrence?

2. How plausible are the basic parameters presupposed by the hypothesis?

. . . . .

[A]lthough this basic structure of historical arguments is so immensely important and its disregard inevitably leads to wrong, or at least insufficiently reasoned, conclusions, it is not a sufficient condition for valid inferences. Historical data does not come with tags attached to it, informing us about (a) how – or whether at all – it relates to one of the two categories we have mentioned and (b) how much plausibility it contributes to the overall picture. The historian will never be replaced by the mathematician.23

23 This becomes painfully clear when one considers that one of the few adaptations of Bayes’s theorem in biblical studies, namely Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix, 2014), aims to demonstrate that Jesus was not a historical figure.

Heilig, Christoph. 2015. Hidden Criticism?: The Methodology and Plausibility of the Search for a Counter-Imperial Subtext in Paul. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 26f

One blogger is looking for old communist-era publications explaining Jesus as a mythical figure. I have had a similar interest in the sorts of things that were said about Jesus and Christian origins in the Soviet Union. I know Engels wrote something and that Drews impressed Lenin enough for him to propagate his views throughout the new Russia. See, for example, https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.slq.qld.gov.au/stable/309549

For some reason Kalthoff comes to mind but I can’t recall any specific link between his work and education in the Soviet Union.

If anyone knows specific works that directly answer this query please do leave a notice in the comments. (That is, I am only interested in links that identify titles/names that were published as arguments for the nonhistoricity of Jesus for readers/students in communist nations.)

My request is much the same as our blogger friend whose post, in translation, reads:

. . . . I pray for your help. . . . . During the time we lived in Romania, I visited the antiques as many times as I had the opportunity. Once (I think in Sibiu) I entered an antique shop that had some books on religion from the time of the communist period. I found them interesting but strange, presenting Jesus as a purely mythological person with traits and characteristics taken over from previous mythological people and gods. Then I did not foresee any occasion in which I would need communist propaganda like this and so I left the books on the shelf and did not buy them.

Now, I’m sorry for that decision.

Since then, between English speakers, this idea of communist propaganda has become very popular in Internet communities. It would be the case for somebody (either I or others) to write a history of this idea that involves the crusade against Christianity during the Cold War.

I would start this project, but I encountered a problem. I do not have access to the necessary books because of the mistakes made many years ago in an antique shop in Romania.

I did not write this blog post just to advise you not to make the same mistake. I hope that some of my relatives and friends in Romania, or your friends and acquaintances, have some books like this, or to guess where I can find them either in a library or in an antique, in a personal collection.

That’s two of us now with the same request.

As a footnote, I am reminded here of the same blogger’s (somewhat amusing) response to my reference to Eric Hobsbawm’s point about historical methodology:

In no case can we infer the reality of any specific [hero, person] merely from the ‘myth’ that has grown up around him. In all cases we need independent evidence of his actions.

In the context of our controversial topic those words by Hobsbawm sounded like the methodology of a communist propagandist to our friend:

You (and Hobsbawm) are free to adopt this approach, of course, but might Hobsbawm’s desire to rewrite the legacy of Communism suggest that his statement has more to do with ideology than mainstream historiography?

Interesting to compare another historian’s comment on the soundness of Hobsbawm’s methods as a historian.

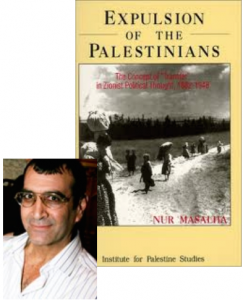

Previous posts in this series covering Nur Masalha’s book, Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948: . . .

Previous posts in this series covering Nur Masalha’s book, Expulsion of the Palestinians: The Concept of “Transfer” in Zionist Political Thought, 1882-1948: . . .

. . .

Zionist leaders were always alert for opportunities to work with Arab countries that neighboured Palestine in hopes they could assist with plans to transfer the Arab population out of Palestine. Earlier we saw one such attempt to negotiate a plan with Jordanian leaders (1937), and in 1939 another hopeful meeting to work with the Saudi Arabian king was organized.

The plan was to promise King Ibn Saud a major role in a future Arab federation and more immediately to provide him with substantial financial aid to resolve economic hardship his kingdom was at that time enduring.

To approach the Saudi king the Zionist leaders happily found willing support from Harry St John Philby, British orientalist and advisor to the king [see the Wikipedia linked article for his “colourful” career and that of his son]. Philby’s contact in London was the famous British historian Lewis Namier who was closely associated with the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann and was the political advisor to the Zionist Jewish Agency led by Moshe Shertok.

Continue reading “Ideological Preparation for the Expulsion of the Palestinians, Continued”

From the previous discussion it can be established that denialism does not mean disagreement with the majority or even with the “everyone else” in the field or for having stand-alone “politically incorrect” beliefs: it is possible to disagree with “everyone” yet not be a denialist. How so? Richard Evans explained it by comparison of David Irving with another prominent historian I have also discussed from time to time, Eric Hobsbawm.

Further to the right of O’Brien, the columnist ‘Peter Simple,’ writing in the Daily Telegraph, considered it a “strange sort of country” which could consign Irving to “outer darkness while conferring the Order of Merit on another historian, the Marxist Eric Hobsbawm, an only partly and unwillingly repentant apologist for the Soviet Union, a system of tyranny whose victims far outnumbered those of Nazi Germany.” Leaving aside the numbers of victims, and ignoring the fact that Hobsbawm was not awarded the Order of Merit, which is in the personal gift of the queen, but was appointed a Companion of Honour, which is a government recommendation, the point here was, once more, that Irving did not lose his lawsuit because of his opinions, but because he was found to have deliberately falsified the evidence, something Hobsbawm, who in his day has attracted the most bitter controversy, has never been accused of doing, even by his most savage critics. (Evans , 238f)

I have heard the term used to describe Holocaust deniers, creationists (the young-earth kind), climate change sceptics, anti-vaxxers, and probably some others that don’t come to mind right now. (Oh yes, now I remember. Some people apply the term to those who are not convinced that Jesus was a historical figure.)

Do all of those groups share something in common that earns them the label “denialist”? What is it that each of those ideas has that sets them apart from intellectual positions that cannot be seen as “denialist”?

With this question in mind I had a closer look at Holocaust denial. I had accidentally come across a movie about the David Irving and Deborah Lipstadt trial and that led me to reading as a follow-up . . .

I liked Richard Evans’ book on history as a discipline and the challenges it was facing with certain postmodernist inroads, In Defence of History (1997), so I was especially interested in his reflections on his experience as the specialist historian witness in the Irving trial. (I’ve addressed aspects of Evans’ In Defence of History several times on this blog.)

Some years back I was curious to understand what Irving’s arguments were about the Holocaust so I purchased second hand copies of Hitler’s War and The War Path and was bemused. I couldn’t see what people were complaining about. I failed to realize that all the fuss was about his second edition (1991) of those books. I had read the 1977 and 1978 works.

David Irving can be considered the “father” of Holocaust denial. So what is it about his work that makes it so? I select passages from Richard Evans’ conclusions about Irving as a historian. I highlight sections I find of special interest. Continue reading “Understanding Denialism”

Through a Haaretz article by Amir Tibon I learned of a new Pew Research Center Poll: U.S. Public Has Favorable View of Israel’s People, but Is Less Positive Toward Its Government

One might hope that the title alone of the results of that survey will go some way towards demolishing the slur that criticism of Israel’s governments’ respective policies is a subtle form of anti-semitism.

Disappointingly predictable was the finding that Christians (notably the evangalical side of Christianity) are more likely than Jews and the “religiously unaffiliated” to approve of Trump’s hardline stance in support of Israel’s policies (presumably towards Palestinians).

Overall, it showed that 48 percent of Christians – including 61 percent of Evangelicals – have a favorable view of the Israeli government. However, a plurality of Catholics – 49 percent – have a negative view of the Israeli government, and so does a big majority – 61 percent – of Christians who belong to the historically black church. (Tibon)

Evangelical Protestants are more likely than non-evangelicals to express a favorable opinion of Israel’s government (73% of evangelical Republicans vs. 55% of non-evangelicals) (The Report)

As I’ve experienced in other areas, more Catholics than fundamentalists are on the side of liberalism, social justice and support for oppressed populations, and the support for Trump’s position towards Israel is less among Catholics than among fundamentalists and evangelicals. Bring on Armageddon, I can hear the latter half-silently hoping. “God will bless those who bless the descendants of Abraham!”

Interesting that American blacks even today appear to continue to identify in some sense with the Palestinians. (That notion of identification on the part of American blacks has been a controversial question in the past.)

Jews are not quite as totally gung-ho:

Among Jewish respondents, 42 percent said that Trump’s policies were too favorable to Israel. Only 6 percent said that his policies were too favorable to the Palestinians, while a plurality of 47 percent said the policy struck the right balance. Among Christian respondents, meanwhile, only 26 percent said Trump’s policies were too favorable to Israel, while 59 percent said the 45th president has the ‘right balance.’

The sample size was about 10,500 and error margin estimated at 1.5%.

Sometimes a book is delivered in the post to me in packaging that is, well, curiuous.

I recently received a huge cardboard carton that felt very light and wondered what on earth it could be. I opened it to find at the bottom a very, very thin book that a publisher had sent to me for reviewing. (A task I have still to do.) Why? presumably it was oversize by height and/or width for normal packing so the next extreme step was the only alternative.

But yesterday was something else. This was one of those bags that you imagine is used for a sack of potatoes but it was marked “Swiss Post”. It was tied up in the middle with one of those plastic twist ties and delivery label and down at the bottom of the bag was the book you see beside it in the photo.

It’s a heavy book. Perhaps that had something to do with it. But strange. Very strange indeed.

Many of you took special notice of my post (Another Name to Add to the Who’s Who Page of Mythicists and Mythicist Agnostics) about Narve Strand and his response to Bart Ehrman’s arguments for the historicity of Jesus.

Narve Strand has since uploaded a new version of that article, partly as a result of the Vridar discussion thread. He has added qualifiers to hopefully clarify some of the questions that arose over his presentation. He has also entered some new references and updated his CV.

So replace all your copies of the original with the new version:

My post “The Chosen People Were Not Awaiting the Messiah” led to more diverse comments than I had been expecting and I thought I should cover a little more of Akenson’s grounds for his view that there is no unambiguous evidence for popular messianic expectations as part of the background to the life of Jesus — or anytime between 167 BCE and 70 CE. I was attracted to this aspect of his larger discussion in Surpassing Wonder: The Invention of the Bible and the Talmuds because it is a view I have addressed several times over the years here. It’s always nice to meet someone who agrees with us. Akenson could be wrong, of course, but I find the balance of evidence (or rather lack of evidence) coupled with what I think is sound analysis leaves me thinking that it is a myth that many Jews were eagerly anticipating a messiah to deliver them from the Romans. (The myth arose, I suspect, as a spin-off from the post 70 CE Christian narrative.)

So here is a fuller account of Akenson’s argument.

The Messiah concept in the “Old Testament” is a peripheral idea that has no clear relationship with our concept of a future conquering and redeeming saviour figure. “Anointed ones” (translatable as “messiahs”) referred to kings (good and bad ones), to prophets and mortal high priests. Yet scholars have tended to look for some notion of the later Christian and/or rabbinic idea of messiah in other places in the Tanakh where the word is not found. At this point Akenson makes a point and quotes a scholar I have also quoted several times to make the same point:

Granted, there are such things as sub-texts and arguments-from-silence, but the forcing of Moshiah into places where the writers did not use the term is surpassing strange. As William Scott Green has noted, this forced exegesis seems to “suggest that the best way to learn about the Messiah in ancient Judaism is to study texts in which there is none.”

But what about the extra-biblical Judean writings between 167 BCE and 70 CE? Apart from the Dead Sea Scrolls there are only two surviving documents that mention the messiah. Of the passages in the Book of Enoch, or in those chapters (37-71 — the Similitudes or Parables) written during this period, Akenson writes

In two places (48:10 and 52:4), the term Messiah is used, but in a strangely subordinate form: as if referring to an archangel rather than to an independent figure. In the first instance, a judgement is announced against those who “have denied the lord of the Spirits and his Messiah,” and in the second, an angel explains to Enoch that at the final judgement Yahweh will cast a number of judgements, which will “happen by authority of his Messiah….” Apparently, in the latter case, Moshiah would not be an active participant in events, but rather, the guarantor of their authenticity.

Of the passage in the Psalms of Solomon,

In the Songs of Solomon, hymns number 17 and 18, there is found praise of “the Lord Messiah,” a future super-king of the Davidic line who will destroy Judah’s enemies and purge Jerusalem. Whether the voice here is closer to old-time classical prophecy or to later Second Temple apocalyptic rhetoric, is open to question. The clear point is that Messiah is a king who will reign in the manner of a powerful and righteous monarch. This is not a piacular or redemptive figure, but an Anointed One, in the same sense that King David was.

In sum, then, Continue reading “Were Jews Hoping for a Messiah to Deliver Them from Rome? Raising Doubts”

Warning: For new readers only. This post is essentially a repeat of a March 17th post this year. So if you were not paying attention back then . . . .

Warning: For new readers only. This post is essentially a repeat of a March 17th post this year. So if you were not paying attention back then . . . .

Once again a forum post I wrote over a year ago, Rules of Historical Reasoning, has come in for indirect attention from Religion Prof.

When sharing a recent blog post on social media, I offered some thoughts on how academic study works at its most basic level. Here is what I wrote, with some minor improvements and alterations to the wording:

Reading some online discussions, you’d think that there is a need for people on those blogs and discussion boards, with no particular expertise in or professional connection with the study of history, to come up with their own methods for historical study. Not that they don’t talk about what historians and scholars past and present have done and do. But they talk about the methods as though they themselves actually use them regularly to investigate historical questions and so are poised to assess their value, and indeed better poised that professionals who do in fact use them, daily.

The “discussion boards” link is to my forum post. Far from suggesting that my post in any way implied that amateurs do or should “come up with their own methods for historical study” the whole thrust of the post was that academic historians explain and justify the methods that they, as academics, use. And far from suggesting that biblical scholars investigating the question of the historical Jesus “do in fact use” those same methods, the whole thrust of the post was that as a rule biblical scholars addressing the historical Jesus part company with their historian peers in non-biblical fields.

The same criticism of my post was made in mid March this year and I responded at that time with a copy of my forum post. I copy that forum post again here, but preface it with a link to a fuller discussion by a historian of ancient history of some renown, M. I. Finley:

An Ancient Historian on Historical Jesus Studies, — and on Ancient Sources Generally

Rules of Historical Reasoning

From Mark Day, The Philosophy of History, 2008, pp. 20-21.

Continue reading “How Scholarship (especially historical research into almost any topic except the historical Jesus) Works”

One widely held view that I have long questioned is that there were widespread expectations or hopes for a soon-coming messiah around the time of Jesus. One line of evidence often cited in support for this scenario are the scrolls from Qumran. I have posted regularly on the evidence and what various scholars have had to say about it, and now happily (for me) I have found one more scholar who has likewise questioned the prevailing assumption and specifically pointed to the failure of the Qumran scrolls to indicate the existence of messianic fervour or imminent hopes prior to the Jewish War of 66-70 CE. The author speaks of Judahism to distinguish the religious ideas and practices of later (200 CE – 600 CE Judaism).

Three characteristics of the apparently Messianic usage of the Damascus Document are noteworthy. First is the way that this Moshiah – whom one would expect to be central to the discussion – is only mentioned briefly, almost with a passing nod. The concept of Messiah is there, certainly, but the Damascus Document almost says that, really, it’s no big deal. This is very curious indeed. Secondly, there is the matter of the title “Messiah of Aaron and Israel,” or, more accurately, “Anointed One of Aaron and Israel.” This seems to apply directly to a future High Priest, for it is to Aaron that the competing high priestly lines traced their ecclesiastical ancestry. So the future Moshiah will be a High Priest with the proper credentials. This position, that Messiah will be a proper High Priest, is buttressed by a fragment from Qumran Cave No. 11 (again if, and only if one accepts that this document comes from the same belief system as does the Damascus Rule). This fragment is an apocalyptic piece in which Melchizedek is presented as the active agent of God, and Moshiah as the messenger of Melchizedek. Messiah is identified as the man “anointed of the spirit about whom Daniel spoke” (11Q Melchizedek 2:18). The reference almost certainly is to the high priest who is forecast in Daniel’s prophecy of the “seventy weeks.” Thirdly, in what seems to be a related Qumran document, one given the name “Rule of the Community,” or “the Community Rule,” there is a fleeting eschatological reference to the way the religious community in question was to be run “until the prophet comes, and the Messiahs of Aaron and Israel” (Rule 9:11). Note the plural. From this many scholars have concluded that not one, but two Messiahs would appear to redeem the righteous. This belief in two Messiahs is injected thence into the Damascus Document, with the assertion that “Messiah of Aaron and Israel” really means Messiahs of Aaron and Israel, and is best differentiated as meaning “Messiah of Aaron” and “Messiah of Israel.”

This is not bad scholarship, but it certainly is confusing eschatology. What, indeed, did the texts in the Qumran library mean when they referred to Messiah? We must remain confused, because the authors of the documents were confused. The concept of Messiah in the Qumran documents is neither central, nor is it very well thought out, and these judgements hold whether one wishes to read the Qumran manuscripts as independent and unrelated items, or as texts that dovetail into one another.

Yet, consider the context in which these Qumran documents were found; in a library that included copies of various complex texts that were basic to the Judahist tradition. These ranged from entire sets of what later became the canonical Hebrew scriptures (save for the Book of Esther) and big and complex volumes, such as the Book of Jubilees and the Book of Enoch. This means that whoever wrote the four Qumran documents I have referred to above, almost certainly knew how to frame complicated and important concepts within the tradition of Judahist religious invention. Yet, despite this knowledge, the concept of Messiah is left so vague as to be almost evanescent. (That we cannot be sure whether the belief was in one or in two Messiahs is vague indeed.)

This leads to a simple conclusion, but one that most biblical scholars – especially those whose background is the Christian tradition – being dead keen to find any Messianic reference, resist: that the concept of Messiah was only of peripheral interest to later Second Temple Judahism.Even if one speculates that future scholarship on the Qumran libraries may produce from the remaining fragments as many as half-a-dozen more possible references to an Anointed One, or Anointed Ones, it still would not shake the basic point. As indicated by the contemporary texts – the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Apocrypha, and the Pseudepigrapha – Messiah was at most a minor notion in Judahism around the time of Yeshua of Nazareth. The Chosen People were not awaiting the Messiah. (175-76. Italics original. Bolding mine.)

Akenson, Donald Harman. 2001. Surpassing Wonder: The Invention of the Bible and the Talmuds. New edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Here’s a snippet of something I came across while venturing into all sorts of pathways to check the claims of, and/or to learn the background to, various publications by scholars of some note.

The common starting-point of all three writers [Smith, Robertson, Drews] is that the earliest Gospel narratives do not “describe any human character at all; on the contrary, the individuality in question is distinctly divine and not human, in the earliest portrayal. As time goes on it is true that certain human elements do creep in, particularly in Luke and John…… In Mark there is really no man at all; the Jesus is God, or at least essentially divine throughout. He wears only a transparent garment of flesh. Mark historizes only.”

. . .

“The received notion,” adds Professor Smith, “that in the early Marcan narratives the Jesus is distinctly human, and that the process of deification is fulfilled in John, is precisely the reverse of the truth.” Once more we rub our eyes. In Mark Jesus is little more than that most familiar of old Jewish figures, an earthly herald of the imminent kingdom of heaven; late and little by little he is recognized by his followers as himself the Messiah whose advent he formerly heralded. As yet he is neither divine nor the incarnation of a pre-existent quasi-divine Logos or angel. In John, on the other hand, Jesus has emerged from the purely Jewish phase of being Messiah, or servant of God (which is all that Lord or Son of God implies in Mark’s opening verses). He has become the eternal Logos or Reason, essentially divine and from the beginning with God. Here obviously we are well on our way to a deification of Jesus and an elimination of human traits; and the writer is so conscious of this that he goes out of his way to call our attention to the fact that Jesus was after all a man of flesh and blood, with human parents and real brethren who disbelieved in him.

(Conybeare 85f. My highlighting)

I use to accept Conybeare’s “obvious” overview of the development of Jesus in the four gospels. The progression of Jesus from human to increasingly divine was, after all, one of the themes that pointed to the sequence in which they were thought to have been composed. First, the crude Mark with his bumbling Jesus who needs a few attempts to heal sometimes, then the more exalted Jesus who passes through life with more poise and control, even showing his post-resurrection self to his followers, then Luke’s Jesus who vanishes before people’s eyes and reappears in the middle of a closed room, and finally the most thoroughly divine Jesus in the Gospel of John. Continue reading “Once More We Rub Our Eyes: The Gospel of Mark’s Jesus is No Human Character?”

I’ve had a break from posting for a couple of days. The reason: I’ve been pulled in to reading the rest of Akenson’s book, Surpassing Wonder. Akenson is known primarily as a historian of Irish history but he has obviously kept abreast of the scholarship in biblical studies, too. What intrigued me most as I read was the striking way he presented certain views of “how the Bible came to be” that I have favoured — but his arguments were more direct and forceful than I have been prepared to acknowledge in posts.

He addresses problems with the “Documentary Hypothesis”, noting that it is not really a hypothesis but a model and should more correctly be called the Documentary Model: that is, the view that the Pentateuch and some other biblical texts are sourced from Yahwist, Elohist, Deuteronomist and Priestly sources. Now the final product may have been stitched together from such sources, but, Akenson notes, that is irrelevant to the study of the narrative and meaning of the final text as we have it. And what’s more, there was a single authorship of the nine books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings. (I’ve posted about that view of the “Primary History” before.) I especially liked Akenson’s tracing of the main stages in biblical scholarship pertaining to the “DH” since it helped me place in context several of the big name scholars I have been studying up till now.

Yes, there are archaisms in the books, and there are repetitions and contradictions, but we have some of the same sort of things in Greek histories, too, and they serve a purpose, in particular the purpose of “authenticity” as a “historical record”. The difference is that the biblical history is anonymous. And that detail, too, has the effect of adding authority to the account. Many readers, especially believers, have liked to comment on the low-key matter-of-fact way many of the more dramatic and miraculous events are described in the bible. That style, believers say (as I have done myself), suggests authenticity, too. It works as narrative history.

Then carry over the style and techniques to the gospels and we have an ongoing account that sounds “genuine”. What is particularly striking in this context, furthermore, is the discussion of how Second Temple era literature managed to continue, build on, “biblical narratives” but at the same time dramatically re-write them, even introducing new characters, even spirit ones, to let God off from being blamed from some horrible decisions, and even claiming to be directly quoting God himself, without a mediator like Moses. It puts the gospels in an interesting context.

Anyway, that’s where I’ve been hiding these last couple of days. More later, I am sure.