If it fits. . . .

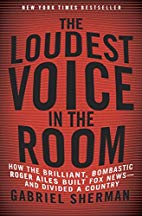

I live in Australia but some things I have seen of ardent Trump supporters seem . . . not entirely desirable. Am I mistaken for thinking that there is a certain clamorousness, a certain closed-mindedness against the views of “the other”? Back in 2007 I posted 10 characteristics of religious fundamentalism and earlier today I ran through the points and wondered. . . .

1. They (fundamentalists) are counter-modernist. It (fundamentalism) manifests itself as an attempt by “besieged believers” to find their refuge in arming themselves with an identity that is rooted in a past golden age. And this identity is acted out in an attempt to restore that “golden past”.

My impression: They (Trump supporters) are opposed to “liberals” and what we might see as progressive liberal values, yes? They like the idea of tossing aside all that PC speak, for example, and just going back to the common-sense world of the old days, — Americans, tell me if I’m right. Also, to get America back where it was when it “was great” — with car manufacturing jobs etc abounding again. And what’s with all the rules trying to stop people driving SUVs and dumping waste into rivers? It even extends to envisioning some sort of biblical Israel restored at their behest.

-o-

2. They (fundamentalists) are “generally assertive, clamorous, and often violent”.

Oh yes. I don’t think there is much doubt there, is there?

-o-

3. They are “the Chosen”, “the Elect”, “the Saved”. And as such, they are “privileged” or “burdened” with a special mission on behalf of their deity and for the benefit of the world. . . . “To be chosen is to be marked for a superior fate; one is marked by virtue of being superior“.

Those are religious terms. Is it fair to think there is an analogy, though? They certainly seem to me to look down upon those who are still somehow lost in the “extreme left”, “liberal values”, “Democrats…”, so much so that they don’t need to listen to them seriously. And we do have “white supremacists” among the Trump supporters. America should be for Americans, yes, so a wall is needed to keep out those not part of “the elect”.

-o-

4. Public marks of distinction are needed to maintain their sense of superiority and distinctive identity. Not only for the purpose of maintaining that distinctive identity, but also as “part of the narcissistic struggle to be considered unique and special.” (p.30)

Do MAGA caps count?

-o-

5. There is only one true religion and one correct way of life; and these must be defended against inroads from other religions and secularism.

And that true way of life sure as hell doesn’t include “PC nonsense”. And it has to be defended against criminals and other subversives from over the southern border; and from “socialists” and “greenies”, and “the deep state”, and the “fake media”.

-o-

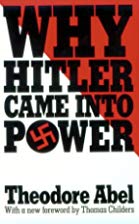

6. There is an inerrant holy book, prophet or charismatic leader to whom literal obedience is mandatory.

No holy book or Mein Kampf can come from a semi-literate. And can the leader do any serious or real wrong? It seems not. Accusations to the contrary are entirely fake, we are told. And the only view worth listening to, it appears, is the leader’s. All others are “fake”. Simply ignore them. Deny them. Mock them.

-o-

7. Law and authority come from God.

Evangelical supporters of Trump think Trump is God’s agent. Other secular supporters appear to think that they subscribe to a “higher law” that has the right to thumb its nose at the way things have always been done, at the Constitution and legal procedures, the latter being redefined according to the will of Trump. There is clearly an authoritarian streak.

-o-

8. Female sexuality must be controlled and clear impassable boundaries must be established between men and women.

Abortion is now deemed to be a crime.

-o-

9. Sexual behaviour is a major concern of all fundamentalists — Christian, Jewish, Islamic — without exception. Especially the fear of and opposition to homosexuality.

I don’t know if there is anything of note here apart from the Fundamentalist church groups who support Trump. Trump has known how to align with this demographic. Is homosexuality an issue beyond the Christian supporters?

-o-

10. Fundamentalism and nationalism converge. The moral life according to the will of God can only be fully lived in a society of fellow-practitioners of the belief. This can only be achieved through God’s rule — through the national executive and legislature itself. Hence the importance of bringing about a government that will prioritize the right morals and right culture for the nation — relegating other (economic) functions to a secondary place.

Oh yes. Definitely.