Let’s move from France in the 1970s and 80s to the USA, specifically Los Angeles, in the 1960s. In this post I address another frequently cited work in the subsequent literature:

- Sears, D.O., and D.R. Kinder. 1971. “Racial Tensions and Voting in Los Angeles.” In Los Angeles: Viability and Prospects for Metropolitan Leadership, edited by Werner Z. Hirsch, 51–88. New York: Praeger.

In the previous post we saw cultural racism emerging in Europe; in this post we look at Sears and Kinder study what is termed symbolic racism. Symbolic. It sounds innocuous, doesn’t it. Not real. But that’s far from its intended meaning.

The occasion of the study by Sears and Kinder was change in Los Angeles and southern California in “rolling back the generous Democratic liberalism of the early 1960’s and replacing it with a tense and preoccupied conservatism” with the victory of Ronald Reagan (p. 52). My interest and focus is on understanding what lies behind the term “symbolic racism”.

Compared with the 1950s the dominant views and attitudes towards blacks among voters in Los Angeles by 1970 were racially liberal.

Respondents do not believe in racial differences in intelligence, and there is virtually no support for segregated schools, segregated public accommodations, or job discrimination. Moreover, most of the sample recognizes the reality problems that blacks face in contemporary American society. They perceive Negroes as being at a disadvantage in requesting services from government, in trying to get jobs, and, in general, getting what they deserve. And they feel that integration can work: they feel the races can live comfortably together. . . .

No doubt they feel rather moral on racial grounds and would hotly deny the contention that they are “white racists.” Indeed, they seem to have learned quite thoroughly those moral lessons conventionally taught a decade or two ago, and they represent that way of thinking rather well. It is just that they are ten or fifteen years out of date now. The attitudes that characterized a “racial liberal” in the middle 1950’s are not enough to keep one from being perceived as a “racist” in 1970. (p. 63)

Nonetheless, despite being “racial liberals” by the standards of the 1950s, it was still discovered that

racism was the single most important predictor of mayoralty voting in our survey.

So what is meant by racism? Sears and Kinder distinguish four types of racial attitudes.

1. Race equality/inequality

First, there is the traditional crude racial stereotype that deems blacks as inferior by nature. I presume that is the dominant 1950s racism. But most voters surveyed believed in a racial egalitarianism: blacks should attend the same schools as whites; blacks should have complete access to all public facilities; an equal chance in the job market; having black friends, and so forth.

The majority of white voters by 1970 were “racial egalitarians”.

2. Reactions to personal experience

The survey found that voting decisions bore no corresponding relationship to a voter’s direct experience with blacks. So the amount of contact one had with blacks, the extent of black socio-economic progress compared with their own, etc, made no difference to voting choices.

3. Responses to potential racial threats

Note: “potential”, not experienced. Example question: Would you mind a lot, mind a little, an equal status negro family moving in next door? This brings us a little closer to a positive relationship to voting decisions:

The vote was rather closely related to the perception of potential threats that have not yet materialized, as shown in Table 3.4. The possibility of Negroes bringing violence to the respondent’s neighborhood, the possibility that bussing might take his children to schools in a minority neighborhood, and the possibility that Negroes might move in next door all relate rather strongly to the vote. None of these are greatly realistic fears for this area of Los Angeles (or for any part of Orange County), but all are conceivable. (p. 66)

4. Symbolic racism

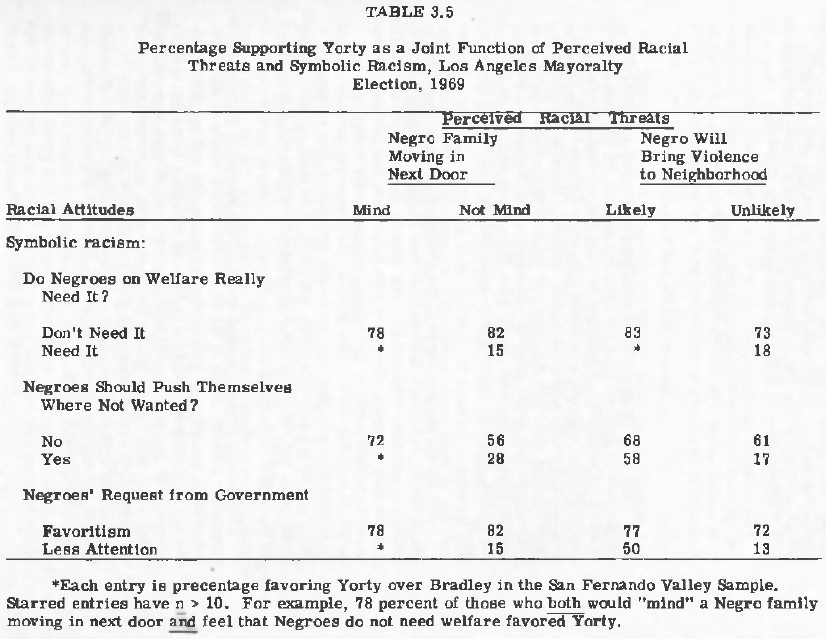

Finally, the most powerful items of all are those that are almost wholly abstract, ideological, and symbolic in nature. These are items that have almost no conceivable personal relevance to the individual, but have to do with his moral code or his sense of how society should be organized. That Negroes are too pushy, that Negroes on welfare are lazy and do not need money, that Negroes get undue attention from government when they make a request—all show very large differences between Bradley and Yorty supporters. That symbolic racism is of greater political importance than racial threats is clearly demonstrated by the data in Table 3.5.

Racial threats contributed little to conservative voting above and beyond the contribution made by symbolic racism. That is, Yorty support was mostly determined by symbolic beliefs, such as that Negroes are too pushy, that they get preferential treatment from government, or that they do not really need welfare money. It made no difference whether or not the white voter also felt racially threatened, whether fearful of Negro violence in his neighborhood or resistant to Negroes moving in next door. Thus, the way in which “white racism” affects voting most is through abstract, ideological, and symbolic issues, rather than by the respondent’s negative personal experiences with Negroes, real or imagined—past, present, or future. (pp. 66 ff)

Origins of Racism

Racism is alive and well at the level of what Sears and Kinder call an “ideological predisposition”.

However, symbolic discontents did relate to racism. The symbolic and ideological origins of white racism are clearly illustrated in the case of the safety, or law and order, issue. In personal form (“women along at night aren’t safe in this neighborhood”), it was not related to racist attitudes . . . but, in symbolic form (“streets aren’t safe these days without a policeman around”), it was. Additionally, the personal form of the law and order issue plays a relatively unimportant role in the respondent’s political beliefs. It is the symbolic version that is politically central: more whites express concern about it, and it is more closely related to conservative voting. (p. 68 f)

Ironically it was found that old voters were more strongly opposed to bussing than younger voters who had school-age children. It follows that symbolic racism is related more strongly to early socialization than to feelings of immediate self-interest. Sears and Kinder point to “a good deal of literature emphasizing the importance of early socialization in the formation of racial prejudice.” The socialization in racial prejudice is found to be predominate among the working class.

The most important social background variable is social class. Whether indexed by educational level, income, or self-classified socioeconomic status, lower status whites are consistently more anti-Negro than are higher status whites. And the differences are quite substantial.

and, and significantly in my view, symbolic racism walks side by side a rejection of the crude 1950s racism that looked down on blacks as patently inferior. Symbolic racism can exist — naively, in S and K’s view — alongside a belief in egalitarianism:

So it appears that “white racism” . . . is a long-standing matter within each individual’s life, dating from preadult acquisition of attitudes and gradually evolving into the “symbolic racism” currently expressed. Its genesis, therefore, seems not to be particularly related to the current racial crisis. From this, and from our respondents’ clear support for generalized egalitarianism, one gets the impression that their racial attitudes are somewhat naive and out of date, rather than respresenting a new retrogression (or backlash) to antiegalitarian ideas.

Conclusions

I omit the details of S and K’s discussion of the evidence for minimal personal contact of many of the white voters with blacks as well as their analysis of the data relating to the influence of the media on racial issues and leap to the conclusion of their study:

In short, the white suburban Californian has the following characteristics:

(a) is racially liberal in terms of general principles of egalitarianism,

(b) is unwilling to accept changes in the status quo that might interfere with his personal life,

(c) has very little personal contact with Negroes, and

(d) is probably hyperresponsive to threatening racial content in the media.

“White racism” in the San Fernando Valley is thus carried on at a largely fantasy level, representing the response of naive and inexperienced whites to symbolically threatening material in the media, which is interpreted primarily in terms of long-standing racial attitudes, unflavored by the reality-testing of personal experience. Since black militants and black violence in the media currently represent his primary contact with the black population the white Angeleno is understandably anxious to preserve both racial isolation and, more generally, the racial status quo. (pp. 72 ff – my formatting)

The point of this post is limited to what it has informed me about the nature and origins of what is termed “symbolic racism” in the professional studies. I conclude with what I take to be some of the more pertinent summary statements of the chapter:

The origins of this symbolic racism appear to lie not in satisfactions or dissatisfactions in the voter’s own life but in the attitudes he acquired much earlier in life. Since the white voter has currently very little personal experience with blacks, his attitudes have both a dated and a naive flavor about them, and he is easily frightened.

. . . .

Symbolic politics emerges most clearly of all. James Wilson has put our major conclusion well: “It is not with their lot that they are discontent, it is with the lot of the nation. The very virtues they have and practice are, in their eyes, conspicuously absent from society as a whole.” Others have discussed these traditional virtues in detail, and they are familiar to everyone, e.g., the work ethic, premarital chastity, postponing gratification, the sanctity of work, the stability of the family, filial gratification for parental sacrifice. Indeed, what we have described derives from “the nagging sense that life is going sour,” not yet in any immediate, personal sense but, rather, in the sense that “the whole society has lost its way.”

Our data do indeed describe a voter whose political responses seem almost wholly divorced from the circumstances of his personal life. It is as if he puts on his “political hat” and then begins to kibitz about matters in which he has virtually no personal investment. We must agree with Wilson’s observation that a democratic system is ill-equipped to handle this sort of moralistic intervention in public life, surely being more successful with the pragmatic resolution of conflicts of “real interest.” Yet, in our present state of knowledge about human happiness, it is difficult to be sure that symbolic gratifications and discontents are less important to a person than those directly concerned with his family, his home, or his work. (p. 80)

We (I’m speaking as a non-American) don’t imagine a person of “liberal” political views to be swayed by racist attitudes, but S and K point out that

when race becomes highly salient, otherwise liberal but racially-anxious whites move to the conservative candidate. (p. 83)

I think we can see the factors addressed by Sears and Kinder in 1970 playing out today well beyond California.

Other posts in this series: Cultural Racism

Other posts in this series:

Understanding Racism (1) – Cultural Racism

Understanding Racism (3) — The New Racism and Commonsense

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Good text on the subject is Loren Goldner Race and the Enlightenment Part 1 Spain, Jews and Indians Part 2 The Anglo French Enlightenment and Beyond at https://thecharnelhouse.org/2017/03/19/race-and-the-enlightenment/ who uses the G. Gliozzi’s italian book Adamo e il nuovo mondo whose subtitle in English is From Biblical Genealogy to Racial Theory.