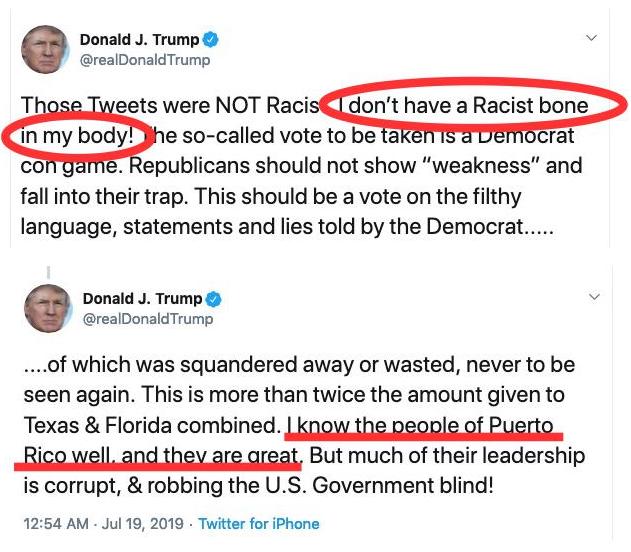

When I read Trump’s tweets. . . .

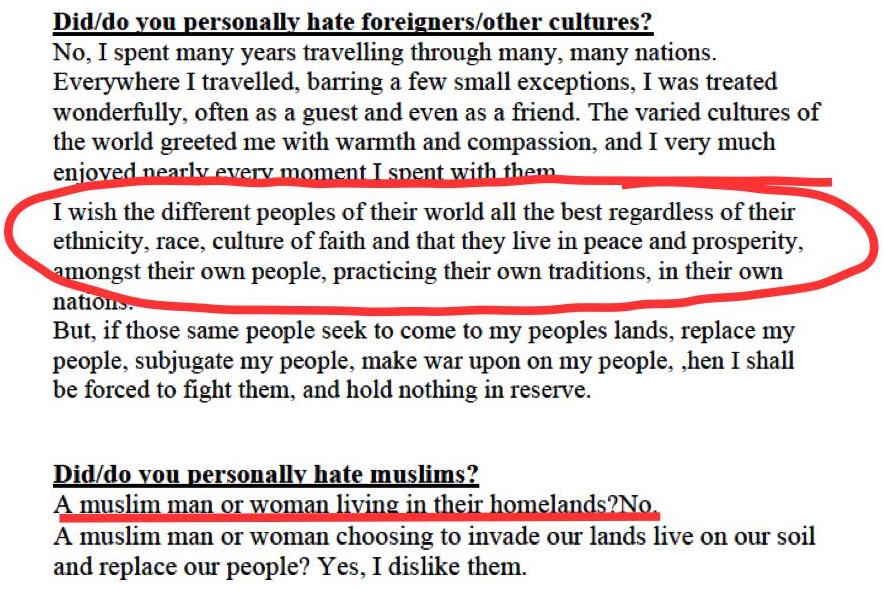

I was reminded of Brenton Tarrant’s words in his manifesto, The Great Replacement:

Brenton Tarrant, you will recall, was the murderer of 51 Muslims in Christchurch, New Zealand. He declared that he had no ill-will towards any race on earth. So long as they stayed in their “natural” borders.

Ever since I posted Strategies of Denials of Racism back in early June I have been trying to get a better handle on the subject. Islam is not a race, of course, so how does anti-Muslim sentiment get mixed up in a discussion of racism? Is it fair or just to brand as a racist someone who feels no ill-will to any other race, does not look down with loathing on another race as if they are in any sense inferior but respects them as “different but equal”?

Since early June I have read a fair amount about racism since the Second World War, and especially since the 1960s and 1970s, and had been toying with the idea of bringing a lot of that reading together for a single post. But now that the time has come I have decided to post about it an easier way. I’ll introduce one by one some of the core readings of mine and over time bring key points together into more integrated discussions.

I begin with an old one, but a good starting point nonetheless:

- Taguieff, Pierre-André. 1990. “The New Cultural Racism in France.” Translated by Russell Moore. Telos 1990 (83): 109–22. https://doi.org/10.3817/0390083109.

Taguieff surveys the way one particular part of the New Right movement in France (the Club de l’Horloge) positioned itself with new arguments that were designed to dissociate itself from the crude racist hatreds of the past (Hitler had given that sort of racism a bad name, after all), from state authoritarianism, and from fascism, and to even throw those labels back on to their left-wing, socialist and democratic opponents. In this post I focus only on the arguments relating to racism.

Traditional anti-racist groups in France were targeted by the New Right as being “anti-French, anti-Western, or anti-White” racists who supported the enemies of France, the West, and White nations. Other New Right factions (e.g. Groupement de Recherche et d’Etudes pour la Civilisation Européene, GRECE) joined with the Club de l’Horloge to reverse the traditional understanding of how racism was defined. Differences, racial and cultural differences, were eulogized.

This praise of difference was reduced to the claim that true racism is the attempt to impose a unique and general model as the best, which implies the elimination of differences. Consequenlty, true anti-racism is founded on the absolute respect of differences between ethnically and culturally heterogeneous collectives. The New Right’s “anti-racism” thus uses ideas of collective identities hypostatized as inalienable categories. (p. 111, my own bolding in all quotations)

Conversely, the racist was now defined as the one who appeared to want to “deny” or “erase” differences between the races, even allowing for a multicultural society where differences were supposedly compromised. Multiculturalism was thus, in effect, branded as “racist” — the view that genuine racial differences should (supposedly) be somehow eliminated.

In the 1970s the “right to be different” was a slogan deployed by the Left in the call for respect for minorities. In the 1980s the same slogan was appropriated by the New Right to mean something different: to claim the right for whites to be different from blacks and for those not belonging to the traditional European culture to be sent back to their ancestral homelands.

Hence in the early 1980s the French New Right presented itself as

against all forms of racism, without any bad conscience or self-hate

Enter Immigration

Continue reading “Understanding Racism (1) – Cultural Racism”