The focus of my response will center on Carrier’s

- claim that a pre-Christian angel named Jesus existed,

- his understanding of Jesus as a non-human and celestial figure within the Pauline corpus,

- his argument that Paul understood Jesus to be crucified by demons and not by earthly forces,

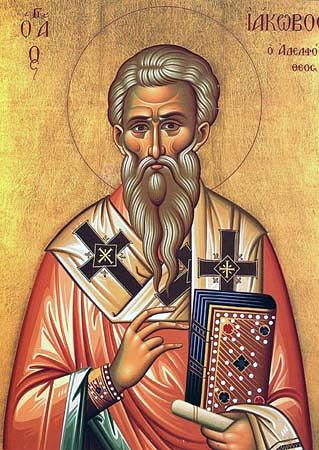

- his claim that James, the brother of the Lord, was not a relative of Jesus but just a generic Christian within the Jerusalem community,

- his assertion that the Gospels represent Homeric myths,

- and his employment of the Rank-Raglan heroic arche-type as a means of comparison.

(Gullotta, p. 325. my formatting/numbering for quick reference)

For an annotated list of previous posts in this series see the archived page:

Daniel Gullotta’s Review of Richard Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus

This is a new page that I have added to the Archives by Topic, Annotated — see the right margin.

–o–

Daniel Gullotta begins is foray into Richard Carrier’s argument that James was a fictive, not biological, brother of Jesus.

It has been claimed that if there is an Achilles’ heel to the Jesus Myth theory, it would be the reference to ‘James, the brother of the Lord’ (Gal 1.19). Typically, historical Jesus scholars take James to be one of Jesus’ many biological siblings; however, Carrier and other mythicists have argued that the familial language used throughout the Pauline letters is reason enough to doubt that James is Jesus’ biological brother.

(Gullotta, p. 334)

Gullotta does not identify any of the “other mythicists” who share Carrier’s argument in his footnote so it appears he knows only Carrier’s mythicist argument. For other arguments about this passage and important background information that needs to be taken into account in its interpretation see any of the other posts addressing these points. Again we are faced with the irony of reading a review that fails to consider opposing arguments in the context of all relevant background information when reviewing a book about the importance of considering alternative hypothesis against all relevant background information.

But the most curious detail of Gullotta’s criticism of this point is his failure to comment on Carrier’s conclusion that he will argue that the passage in Galatians 1:19 is exactly 100% what is to be expected if James indeed was the biological brother of Jesus!

However, I must argue a fortiori, and to that end . . . I’ll allow that it [i.e. Galatians 1:19 being a reference to James’ biological sibling status to Jesus] might be twice as likely on historicity [despite their] internal ambiguity and surrounding silence. . . .

(Carrier, p. 592)

Carrier’s point is to lay out all the evidence and background information and then in that context to compare rival hypotheses or interpretations. That is the essence of the Bayesian method that Gullotta elsewhere indicates he fails to understand. Without that understanding Gullotta is able to do no more than repeat the same proof-text type arguments that are based on scholarly tradition rather than a comprehensive survey of the data.

This is not the first time we have seen Gullotta inexplicably fail to acknowledge that Carrier is prepared to concede for the sake of a fortiori argument the very position Gullotta is arguing! One cannot imagine a more solid evidence that he has failed to understand the whole methodology of Carrier’s argument – or the principles of sound historical reasoning with competing hypotheses.

There is a light-hearted moment in Gullotta’s review, however, when he proceeds to demonstrate his assertion that

there is solid evidence to affirm James was the biological brother of Jesus.

(Gullotta, p. 335)

Hold tight. Prepare for another Gish Gallop. The “solid evidence” appears to consist of

- a list of seven names in Paul’s letters who are said to be a sample of those who are not called “the brother of the Lord”

- James is reputed to be a pillar in the Jerusalem church

- James has authority in the Jerusalem church

- Paul highlights his meeting with him

- James received a vision of the resurrected Jesus

- Paul mentions his name before Peter’s (Cephas’s)

- later traditions said he was a brother of Jesus

- how else can we explain the above unless this James was a brother of Jesus?

“Solid evidence”? No other explanation is plausible than that James must have been a literal sibling of Jesus?

Regardless of the status of Richard Carrier’s specific arguments why not consider the question in the light of all the relevant “background information” as I have attempted to do in Thinking through the “James, the brother of the Lord” passage in Galatians 1:19

Carrier, Richard. 2014. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press.

Gullotta, Daniel N. 2017. “On Richard Carrier’s Doubts.” Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 15 (2–3): 310–46. https://doi.org/10.1163/17455197-01502009.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Has there ever been any scholarly contemplation that James may have been lying in claiming to be “the Brother of the Lord” [which for the sake of argument I will concede to be a reference to Jesus]? After all, look at the context as reported by Paul – he and the leaders in Jerusalem were fighting over which faction’s leadership had the right to control the Christian community’s message and audience. In this environment, it seems possible to me that James may have tried to one-up Paul’s claims to authority by falsely claiming to be Jesus’s brother; in this scenario, other Christians either knew not any better and believed or may have regarded James’s lie as a useful way to rein Paul in and ensure that Christianity only developed in a proper way. This would not be the first time a person, out of desire to preserve a religion in what is allegedly the true way, has lied.

The question to ask is what we might expect to find in the evidence if such a thing happened that cannot be more simply explained by some other thesis.

One thing we might expect to find corresponding to this theory is an absence of plausible corroboration. It would look nothing like the “support” for the brother proposition cited above, but rather it might consist of several eyewitnesses who can describe having seen James grow up alongside Jesus, where they lived, how they interacted, what the difference was in their ages and in their interests, and so on. I don’t think people will ever agree on it.

I address this subject of James in my new book. I haven’t read every argument regarding James, so I don’t know if everything I put forward is new or unique or not, but the case I put forward is one based on my own research. Maybe other people have made similar arguments, I’m not sure, but basically, my argument (which I shared with Richard Carrier many years ago), is that clearly the James who was an important figure in the early Jesus worshiping community was not a literal brother of Jesus because none of the early Christian writings such as the Gospels, Acts, or other early epistles, portray a literal brother of Jesus as having any important role.

It’s obvious that “James son of Zebedee” in Mark is supposed to be the James that Paul identified as the leader of the Jesus cult and the James that he had met. All the early writings focus on “James son of Zebedee”, which would only have happened if this James were supposed to be the James who was a leader of the cult. A James brother of Jesus is totally ignored in all the early works. If James the brother of Jesus were a leader in the community he wouldn’t have been ignored. The author of Luke and Acts never even names the brothers of Jesus and the whole point of Acts was to try and piece together the important history. If the author of Acts thought a literal brother of Jesus named James were a leader of the group he would have said so. The fact that he didn’t makes it clear that whoever wrote Acts surely didn’t think that the James Paul described meeting was a literal brother of Jesus. And obviously nor did the writer of Mark. Nor did the writer of John, which I also address.

I think that “James the Just” and “James brother of the Lord” are basically two ways of referring to this same person using honorary titles that signify his importance. This person was referred to as “the Just” and “Lord’s brother” because of his position of leadership.

The whole business of thinking that he was a literal brother of Jesus is a later confusion that likely starts with Hegesippus in the mid 2nd century.

It seems Robert Eisenman’s books on James and the Dead Sea Scrolls are such hot potatoes that are better not to be touched even by people who write about the non historicity of Jesus. I for sure would not buy a book on the historicity or non historicity of Jesus or James if I know the book avoid discussing Eisenman’s views on the matter.

Although I don’t address Eisenman’s work directly in my new book, my thesis is very comparable with much of Eisenman’s conclusions. In fact I came to many of the same conclusions on my own. While not all of the exact same conclusions are reached, I too find most of Eisenman’s work highly compatible with my view of non-historicity and of the early Jesus cult. I have a whole discussion on Acts that makes many of the same points as Eisenman.

And another thing. Clearly in Galatians, where Paul says he met James, Paul basically contradicts James and says that James is wrong. Paul also says that his knowledge of Jesus is superior to others because it comes from revelation.

Neither of these things make sense of Paul thought James was a literal brother of Jesus. How could Paul’s knowledge from “revelation” compete with the knowledge of the literal brother of the messiah? Paul only discusses his knowledge from revelation because he views revelation to be a MORE DIRECT form of knowledge than what James and other apostles have. Paul is competing against James and the others.

Why would Paul even try to compete against a literal brother of the Lord? That would clearly make no sense.

Certainly it wouldn’t make sense to contemporaries who would have known the historical Jesus had he existed.

Why do you think a “revelation” is necessarily some kind of “spiritual” thing?

“It was revealed to me that Bob embezzeled the money” is hardly a spooky, spiritual thing.

The Greek which we translate as “revelation” (when it’s convenient to do so) derives from the verb apokalyptein, which is a composite of the preposition apo and the verb kalyptein. Kalyptein means to cover, to put something in front or on top of something else, in order to conceal it, either to hide it or in order to protect it. The preposition apo conveys a spacial sense, understood as “away, away from, off, apart, or apart from”. Put together, apokalypsis means “away from cover”, or “apart from hiding” – essentially, “un-concealed”. In English, we might well translate that as “exposed”, and yes, we could translate it as “a revealing”.

(The word is used in the Septuagint in one place to refer to “nakedness”).

What I’m getting at is that it is as foolish to insist on a hardcore translation/interpretation of “apokalypsis” as being some kind of “spiritual revelation” (as it were) as it would be to insist on it meaning “nakedness”.

Paul’s “apokalypsis Jesus Christ” could just as well have been a “revealing of Jesus Christ” through the modicum of ordinary eyesight: Paul SAW Jesus, with his eyes.

Now, I’m not saying that’s what it was. What I’m saying is that it is WAY too much of a stretch to insist that Paul “just had a revelation” (which, we moderns might conclude was an hallucination). There is nothing whatsoever in that word itself (apokalypsis) that forces that kind of interpretation.

Meanings of words are defined through usage. We don’t define the meaning of “fame” by its Greek root φημί meaning “I say”, or “fortunate” by reference to the ancient goddess. No-one says today, and no-one said then in the Greek language, that so-and-so was “revealed” to them if they mean simply that they saw someone.

Simply “seeing” a “risen Jesus” would not have confirmed that he was the “Christ”, nor would it have confirmed that Jesus was “Lord”, nor that he’d been “raised up because of your justification”, nor that God had vindicated and validated Jesus, exalting him. Yet, these are all parts of the “good news” – the “gospel”.

THOSE kinds of “conclusions” cannot be made simply on the basis of having “seen” a “risen Jesus”.

What I’m getting at is that a person can “see” a deceased loved one (for example — as often happens in bereavement hallucinations) – and yet, never, ever conclude that the deceased loved-one is “Christ”, or even “exalted”, or even that they have any special status from God whatsoever.

Paul *does* say he’d “seen” the risen Jesus.

In Galatians 1:12, though, he says , “For I neither received it [the gospel]of man, neither was I taught it, but through ‘apokalypsis’ Jesus Christ”.

He’s talking about having learned THE GOSPEL – that Jesus died for our sins, was raised up for our justification, would never again die, was Lord, was vindicated and validated by God, etc, etc, and etc – “through apokalypsis”. Those kinds of things – ie, that Jesus was the “Christ” (Messiah) of God, that he was exalted by God, that he would never die again, and was raised up for our justification, and so on – THOSE things don’t come from merely seeing a “risen Jesus”. THAT’S the gospel that Paul learned through “apokalypsis”. And, what he’s talking about in Gal 1:12 may not have a thing on earth to do with Paul having “seen” the risen Jesus. People PRESUME it does, but, Paul may be talking about two entirely different things: He SAW Jesus (as per 1 Cor 15), and then the “Christ-hood” of Jesus was what he learned through apokalypsis.

I hope you see my point: You say nobody ever says “that so-and-so was “revealed” to them if they mean simply that they saw someone”, and I’m totally AGREEING with you.

But – NOBODY ever said that what Paul is talking about in Gal 1:12 has anything whatsoever to do with “the time when Paul SAW Jesus”. He could have SEEN the risen Jesus, and still REFUSED to acknowledge that Jesus was “Christ” (and, the rest of the gospel stuff).

UN-DOING SOME HYPERBOLE FROM MY PREVIOUS MSG… (a self-correction)

I said at the end of my previous msg, “NOBODY ever said that what Paul is talking about in Gal 1:12 has anything whatsoever to do with “the time when Paul SAW Jesus””.

That is, of course, not true: LOTS of people have said that Gal 1:12 is supposedly indicative of “how Paul ‘saw’ Jesus” (ie, “in a revelation”).

What I meant by my “hyperbole” is that “it cannot be PRESUMED that what Paul is talking about in Gal 1:12 has anything whatsoever to do with “the time when Paul SAW Jesus”.

(I thought I’d better clear that up from the get-go. I tend to write terribly informally when I shouldn’t)

I am not interested in discussing the things that interest you. Please refer to our policy on comments here.

One of the head mythicists, Dr. Robert M. Price, is very favorable of Eisenman’s analysis. See:

http://www.robertmprice.mindvendor.com/rev_eisenm.htm

http://www.robertmprice.mindvendor.com/reviews/eisenman_nt_code.htm