Or alternatively,

The Cerebral Cortex, the Amygdala, and the Death Penalty

I aspire to embrace humane values and to cage my reptilian impulses to bare tooth and claw. So when I was watching a recent episode of the TV historical drama Poldark and witnessed the death of perhaps its most in-your-face vile and repulsive villains and felt nothing but a sense of pure joy and total satisfaction I had to pause and think.

An online review said it all:

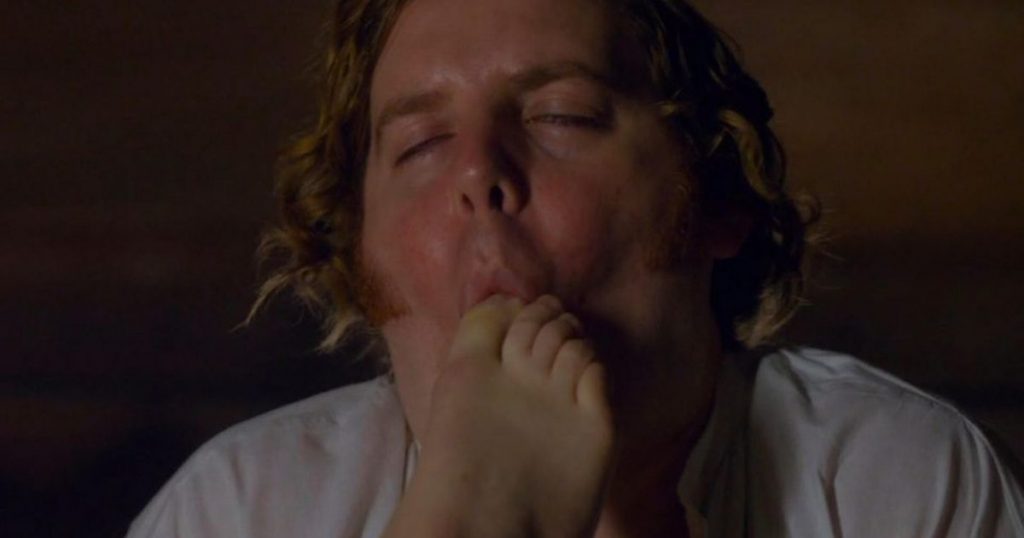

Ossie Whitworth finally got his comeuppance, dragged squealing into the woods after being set upon by Rowella’s husband, and killed in a suitably embarrassing, brutal fashion.

It’s not usually nice to see a Poldark death, but that was particularly satisfying. The greasy, toe-sucking wrong-‘un, so beautifully brought to screen by Christian Brassington, was finally undone by his enormous sexual appetite. And his horse.

. . . . There was a fight, only for Whitworth’s horse to bolt and his lifeless body to eventually ending up bruised, battered and (probably for the first time in his terrible life) limp.

Who could not (at least inwardly) cheer!

So I had to ask myself what happened to my aspirations to human values vis à vis the death penalty.

Oh how shallow is our ethical progress. Give me a different set of parameters, a pre-arranged set of cerebral inputs, and I’m right back to the barbarism of the theatre.

I see now that the Pope has come out against the death penalty, at last, and has confessed that the new ethic is grounded in a new set of cerebral inputs relating to gospel hermeneutics:

The church teaches, in the light of the Gospel, that the death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person and she works with determination for its abolition worldwide.

A related statement expands on that

If, in fact, the political and social situation of the past made the death penalty an acceptable means for the protection of the common good, today the increasing understanding that the dignity of a person is not lost even after committing the most serious crimes.

How historically contingent is our moral progress, and how fragile given our proximity to the end of organized human life.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- Palestinians, written out of their rights to the land – compared with a new history - 2024-10-15 20:05:41 GMT+0000

- The Gospels Versus Historical Consciousness - 2024-10-13 00:48:41 GMT+0000

- “They are Messianic Jewish supremacists, racists, of the worst kind” - 2024-10-07 20:24:10 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!