The Ten Commandments are a strange mix. They proscribe not only stealing and even the craving to have any property belonging to your neighbour. (And neighbour’s property includes his wife.) The command not to kill is certainly not meant to be interpreted literally as a general law since God elsewhere commanded lots of killing of people and animals. Actual laws relating to killing need to cover situations of accidental, impulsive and premeditated killing and the Pentateuch does set out laws covering those variables as we saw in Plato and the Hebrew Bible: Homicide Laws.

The Ten Commandments are a strange mix. They proscribe not only stealing and even the craving to have any property belonging to your neighbour. (And neighbour’s property includes his wife.) The command not to kill is certainly not meant to be interpreted literally as a general law since God elsewhere commanded lots of killing of people and animals. Actual laws relating to killing need to cover situations of accidental, impulsive and premeditated killing and the Pentateuch does set out laws covering those variables as we saw in Plato and the Hebrew Bible: Homicide Laws.

I had expected to be posting one of my final posts on Gmirkin’s book, Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible by now but my study of the final chapter has directed me to a section I covered all too sketchily earlier. So here we are. Back at chapter 4, “Greek and Ancient Near Eastern law collections”.

The Ten Commandments certainly have a distinctive reputation unequalled by any of the other laws in the Hebrew Scriptures. God even commanded for them to be kept in the ark of the covenant, translated as “coffer” in the Everett Fox translation of Deuteronomy 10:1-5, but I have changed “coffer” for the more familiar “ark”:

10:1 At that time YHWH said to me:

Carve yourself two tablets of stone, like the first-ones, and come up to me, on the mountain, and make yourself an ark of wood.

2 I will write on the tablets the words that were on the tablets, the

first-ones, that you smashed, and you are to put them in the ark.

3 So I made a ark of acacia wood,

I carved out two tablets of stone, like the first-ones,

and I went up, on the mountain, the two tablets in my arms.

4 And he wrote on the tablets according to the first writing, the Ten Words

that YHWH spoke to you on the mountain, from the midst of the fire,

on the day of the Assembly, and YHWH gave them to me.5 And when I faced about and came down the mountain,

I put the tablets in the ark that I had made,

and they have remained there, as YHWH had commanded me.

And they do appear to be as much wisdom saying as law, or even more wisdom saying than law. Not only in content, but even in style since, like proverbs they are addressed to the second person “you”. They even address attitudes or feelings that are not even acted upon, which of course is not the sort of thing a “law” typically addresses. Further, their structure facilitates learning and recitation:

The Ten Commandments in Deuteronomy 5:6–21 are an excellent example of teaching structured for memorization. The rules focus on central values of ancient Israel. As Erhard Gerstenberger observed decades ago, their “apodictic” form most closely resembles that of gnomic instructions inside and outside Israel. In addition, the ordering of the list into ten items—however this is done in various streams of tradition—allows the beginning student to use his or her fingers to count off and see whether he or she has included all of the key elements of this fundamental instruction. This combination of elements—focus on central values, simplicity of form, and memorizability—has contributed to the ongoing use of the Ten Commandments in religious education up to the present, along with the focus on them as an icon of central values in contemporary cultural battles over the biblical tradition. (Carr, David M., Writing on the Tablets of the Heart: Origins of Scripture and Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 137 — referenced by Gmirkin, page 204)

Again with the Everett Fox translation, Deuteronomy 5:6-18:

6 I am YHWH your God

who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of a house of serfs.

7 You are not to have other gods beside my presence.8 You are not to make yourself a carved-image of any form

that is in the heavens above, that is on the earth beneath, that is in the waters beneath the earth.

9 You are not to prostrate yourselves to them, you are not to serve

them,

for I, YHWH your God, am a jealous God, calling-to-account the iniquity of the fathers upon the sons to the third and to the fourth (generation) of those that hate me,

10 but showing loyalty to thousands

of those that love me, of those that keep my commandments.11 You are not to take up the name of YHWH your God for

emptiness,

for YHWH will not clear him that takes up his name for emptiness!12 Keep the day of Sabbath, by hallowing it, as YHWH your God has commanded you.

13 For six days you are to serve and to do all your work;

14 but the seventh day

(is) Sabbath for YHWH your God— you are not to do any work:

(not) you, nor your son, nor your daughter, nor your servant, nor your maid, nor your ox, nor your donkey, nor any of your animals, nor your sojourner that is in your gates— in order that your servant and your maid may rest as one-like- yourself.

15 You are to bear-in-mind that serf were you in the land of Egypt, but YHWH your God took you out from there with a strong hand

and with an outstretched arm; therefore YHWH your God commands you to observe the day of Sabbath.16 Honor your father and your mother,

as YHWH your God has commanded you, in order that your days may be prolonged, and in order that it may go-well with you on the soil that YHWH your God is giving you.17 You are not to murder!

And you are not to adulter!

And you are not to steal!

And you are not to testify against your neighbor as a lying witness!

18 And you are not to desire the wife of your neighbor; you are not to crave the house of your neighbor,

his field, or his servant, or his maid, his ox or his donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbor!

Of particular significance for Russell Gmirkin’s thesis is that these Ten Commandments have no known parallel in ancient Near Eastern law codes.

So were the authors of the Decalogue bestowed with a superior gift of spiritual insight?

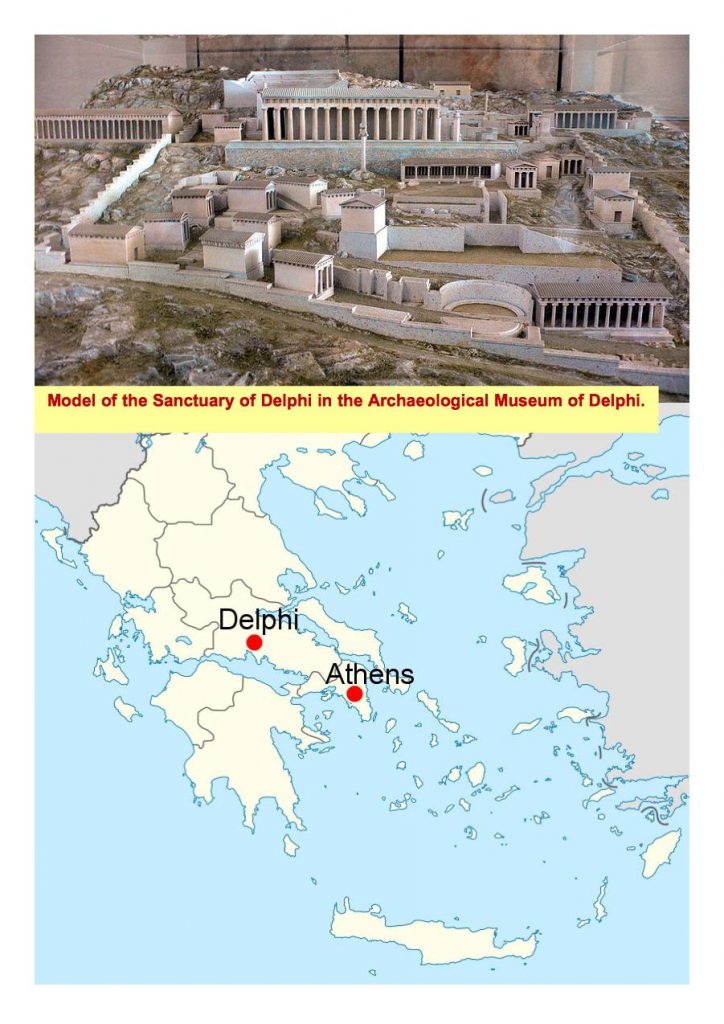

Or were they influenced by “best ideas” of sacred law and wisdom found in a culture to their west? Should we consider a set of “laws” or “sacred sayings” inscribed in stone at Greece’s principal temple at Delphi? The Delphic sanctuary was the centre for Apollo and city-states would send ambassadors to the site to seek guidance from Apollo’s prophetess there.At that holy site was a world-renowned inscription of wisdom sayings that took on the status of sacred laws.

The popular attribution of these commandments to the Seven Sages of antiquity gave these ethical maxims an informal legal stature, because the Seven Sages were all famous lawgivers. The prominent display of the Commandments of the Seven Sages in the most revered of all Greek temples gave these wise commandments an aura of divine sanction, much like the tablet inscribed with the Ten Commandments said to reside in the ark of the covenant within the Jewish temple (Ex. 25.16; 40.20; Deut. 10.5; 1 Kgs 8.9). (Gmirkin, pp. 204f)

Copies of the “Delphic Commandments” were made and engraved in other public monuments that came under the sway of Greek influence in the wake of Alexander the Great’s conquests.

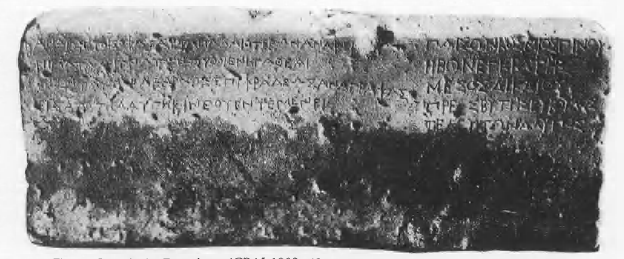

Excavating the Greco-Bactrian city at Ai-Khanum in Afghanistan, the French archaeologists of the field-team were extremely happy on the 22nd of October 1966. What they had uncovered on this day was a rather unexpected and very important find. It was a stone base for a stele, with a Greek epigram inscribed in four lines (Fig. 1) and to its right five more lines of ethical commandments. . . .

Its author, Klearchos, was beyond any doubt the far-travelled pupil of Aristotle. . . . However, the interesting story that the epigram narrated to us was something that we had never heard before. The stele, once standing on the base with the epigram, was a copy of the “Commandments of the Wise Men” originally inscribed on a stele dedicated at Delphi in Greece. Klearchos assures the reader that he himself copied the “Commandments” very carefully from the original inscription at Delphi, and that this copy was used for reinscribing them on the stele he dedicated in the shrine of the Greco-Bactrian city’s “hero-founder.” What was the reason for that? Klearchos answers “so that the Commandments will shine far around (to the Asian lands and peoples) the shrine of Kineas.” (Oikonomides, A. N., ‘Records of “The Commandments of the Seven Wise Men” in the 3rd C. B.C.: The Revered “Greek Reading-Book” of the Hellenistic World’, Classical Bulletin, 63 (1987), pp. 67f, referenced by Gmirkin, p. 204)

The “Commandments of the Seven Wise Men” were designed to be a memorable teaching curriculum.

Used as a first school book for the Greek world from the 6th c. B.C. down to the fall of the Byzantine Empire (1453 A.D.) and some centuries beyond it, “The Commandments of the Seven Wise Men” is one of the ‘didactic’ ancient Greek texts that have been preserved by the philological tradition. . . .

And the [Delphic] stele stood in its place for centuries and generations of Greek teachers, philosophers and common men copied it. And the copies travelled to every corner of the Greek world and far outside it after the conquests of Alexander the Great. To be a human being and act like one, as far as the Greeks were concerned, needed not a severe god terrifying the crowds and burning bushes demanding respect for himself by threats of destruction and doom. All that was needed for establishing an ethical law for a nation, a people or a city was to teach the younger generations the wisdom of the past on what one should and shouldn’t do in a human society.(Oikonomides, pp. 68, 73)

Comparisons with the Ten Commandments were also made by Oikonomides, though not particularly favourable one:

In a world where for more than two decades of centuries the Judeo-Christian tradition has been proclaiming as the supreme ethical law of humanity, a severe and primitive group of “Ten Commandments,” the rediscovery and reevaluation of a more perfect ancient ethical law, based on higher cultural standards, is definitely bound to create some questions not easy to answer. The most important of them already stands in front of us: “How can one believe that the “Ten Commandments” represent the direct words of God to Mankind when the pagan ‘Commandments of the Seven’ express a higher concept and a more realistic vision of ethical law?”

. . . . .

We know that “The Commandments of the Seven” is the earliest known didactic collection of Greek wisdom and we know also that it has successfully served Greek education for more than twenty full centuries. Regarding its ethical standard, all we can say is that it stands at a higher level than the Mosaic decalogue without claiming to be the word of any god, at the same time that it teaches total respect and obedience to Divine power. (Oikonomides, p. 73)

Would the authors of the Pentateuch have produced a less ethical set of edicts if they were truly aware of the Greek maxims? I think the larger thesis of Gmirkin answers that question, as does a reading of Plato’s Laws. We will discuss in a future post Plato’s stress upon the requirement that laws should appear to come from the deity and need to be combined with a mix of encouragement and threats, a mix of reason and edict. Like the Greek sayings, however, it is clear that the Pentateuchal laws, the Ten Commandments in particular, were to be regularly recited (and taught to children) as a fundamental part of the community’s education.

These words, which I myself command you today, are to be upon your heart.

You are to repeat them with your children and are to speak of them in your sitting in your house and in your walking in the way, in your lying-down and in your rising-up.

You are to tie them as a sign upon your hand, and they are to be for bands between your eyes.

You are to write them upon the doorposts of your house and on your gates. (Deut 6:6-9, Everett Fox translation)

As Georg Fischer and Norbert Lohfink have argued, this text does not refer to discussion of the commandments, as is often implied by the translations (e.g. NRSV “talk about them”). Instead it commands a constant process of recitation of the texts during all activities of the waking day. As the following text makes clear, this incision of texts on the heart is part of a broader process of writing them throughout one’s surroundings, again paralleling wisdom exhortations to bind teachings on the self (Prov 6:21; 7:3): “bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as an emblem on your forehead, and write them on the door posts of your house and on your gates.” (Deut 6:8–9 NRSV) Recitation, writing, and other forms of reminder are all forms of cultural circulation, ensuring—in the Deuteronomic vision—that Israelites do not “forget” YHWH and the commandments he has given them (Deut 6:12). The chapter concludes with a picture of education, this time a dialogue in which the children ask about the meaning of the statutes and commandments that their parent is constantly reciting (Deut 6:20), and the parent then puts them in the context of God’s rescue of Israel from Egypt, gift of the land, and promise of life and righteousness if the people obey them (Deut 6:21–25)

Similar themes occur again in Deuteronomy 11:18–21, . . . The process envisioned here is one of self- and child-education through constant vocal repetition. Since children in the ancient world typically were included in their parents’ daily activities, parents constantly reciting a text would put that text not only on their own hearts but on their children’s hearts as well. Yet the “teaching” to be recited here is not the typical educational material used in early education of children. Instead, as Georg Braulik has argued, these injunctions to recite “these words” in Deuteronomy 6:7 and 11: 19 refer to Deuteronomy 5–26 as a whole. According to the D vision, this Mosaic corpus, rather than Solomonic wisdom collections of the sort discussed earlier, is to serve as the initial and central focus of Israelite education and enculturation. (Carr, pp. 135f)

I have copied a translation of “Commandments of the Wise Men” below (Oikonomides writes that he wants his translation to be shared along with the note that other translations are possible and valid). There is one significant difference from the Ten Commandments, though. Five of the latter are couched in prologues or little discussions that function as “persuaders”. They present their “thou shalt” edicts in words that explain why the command is being given. Notice the sabbath edict. The first commandment, likewise, gives a reason to have Yahweh alone as god. Others are embedded in carrots and/or sticks. The significance of this difference, or of this sort of presentation of “laws” will be the subject of a future post. (The bolded commands bear a close resemblance to the ten commandments.)

- Follow God.

- Obey the law.

- Worship the Gods.

- Respect your parents.

- Be overcome by justice.

- Know what you have learned.

- Perceive what you have heard.

- Be yourself.

- Intend to get married.

- Know your opportunity.

- Think as a mortal.

- If you are a stranger act like one.

- Honor the hearth (or Hestia).

- Control yourself.

- Help your friends.

- Control anger.

- Exercise prudence.

- Honor providence.

- Do not use an oath.

- Love friendship.

- Cling to discipline.

- Pursue honor.

- Long for wisdom.

- Praise the good.

- Find fault with no one.

- Praise virtue.

- Practice what is just.

- Be kind to friends.

- Watch out for your enemies.

- Exercise nobility of character.

- Shun evil.

- Be impartial.

- Guard what is yours.

- Shun what belongs to others.

- Listen to everyone.

- Be (religiously) silent.

- Do a favor for a friend.

- Nothing to excess.

- Use time sparingly.

- Foresee the future.

- Despise insolence.

- Have respect for suppliants.

- Be accommodated in everything.

- Educate your sons.

- Give what you have.

- Fear deceit.

- Speak well of everyone.

- Be a seeker of wisdom.

- Choose what is divine.

- Act when you know.

- Shun murder.

- Pray for things possible.

- Consult the wise.

- Test the character.

- Give back what you have received.

- Down-look no one.

- Use your skill.

- Do what you mean to do.

- Honor a benefaction.

- Be jealous of no one.

- Be on your guard.

- Praise hope.

- Despise a slanderer.

- Gain possessions justly.

- Honor good men.

- Know the judge.

- Master wedding-feasts.

- Recognize fortune.

- Flee a pledge.

- Speak plainly.

- Associate with your peers.

- Govern your expenses.

- Be happy with what you have.

- Revere a sense of shame.

- Fulfill a favor.

- Pray for happiness.

- Be fond of fortune.

- Observe what you have heard.

- Work for what you can own.

- Despise strife.

- Detest disgrace.

- Restrain the tongue.

- Keep yourself from insolence.

- Make just judgments.

- Use what you have.

- Judge incorruptibly.

- Accuse one who is present.

- Tell when you know.

- Do not depend on strength.

- Live without sorrow.

- Live together meekly.

- Finish the race without shrinking back.

- Deal kindly with everyone.

- Do not curse your sons.

- Rule your wife.

- Benefit yourself.

- Be courteous.

- Give a timely response.

- Struggle with glory.

- Act without repenting.

- Repent of sins.

- Control the eye.

- Give a timely counsel.

- Act quickly.

- Guard friendship.

- Be grateful.

- Pursue harmony.

- Keep deeply the top secret.

- Fear ruling.

- Pursue what is profitable.

- Accept due measure.

- Do away with enmities.

- Accept old age.

- Do not boast in might.

- Exercise (religious) silence.

- Flee enmity.

- Acquire wealth justly.

- Do not abandon honor.

- Despise evil.

- Venture into danger prudently.

- Do not tire of learning.

- Do not stop to be thrifty.

- Admire oracles.

- Love whom you rear.

- Do not oppose someone absent.

- Respect an elder.

- Teach a youngster.

- Do not trust wealth.

- Respect yourself.

- Do not begin to be insolent.

- Crown your ancestors.

- Die for your country.

- Do not be discontented by life.

- Do not make fun of the dead.

- Share the load of the unfortunate.

- Gratify without harming.

- Grieve for no one.

- Beget from noble routes.

- Make promises to no one.

- Do not wrong the dead.

- Be well off as a mortal.

- Do not trust fortune.

- As a child be well-behaved,

- as a youth — self-disciplined,

- as of middle-age — just,

- as an old man — sensible,

- on reaching the end — without sorrow

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Wow, interesting stuff.

I’m presuming there is no biblical material material that mentions the ten commandments that predates Alexander The Great and Hellenization.

I guess that you are talking about the door step mentioned in Deut. 6:9, the so-called Mezuzah (plural) or Mezuzot, if this is the case then we are in bad luck.

1. The ancient door steps were created by wood, this means that the “ex silencio” argument works in their favor.

2. Mezuzah found in Qumran cave 10 and it is dating in Hellenistic ages. The problem here is that they consider the people in Qumran as sectarian called Essenes, this means that they use this argument to claim that the practices are not common.

On the other hand, in Lawrence H. Schiffman review of the book “Discoveries in the Judaean Desert, Vol VI” writes :

“Most of Milik’s Tefillin and Mezuzot date from the first century B.C., while one of each dates from the second. Milik suggests that the custom of wearing the phylacteries on the hand and head during prayers was introduced during the Maccabean period as part of the national and religious renaissance.”

….

“He suggests that the use of Tefillin and Mezuzot did not spread to the diaspora until the first century B.C. when nationalistic sentiments fostered their use.”

….

“A serious question arises in regard to the origin of Tefillin and Mezuzot which Milik dates to the Hellenistic period. Apparently, he is arguing ex silencio: since we have no earlier evidence, the practice cannot be earlier. This need not be so.”

—————————

My personal point of view is that all this can be used to argue that the O.T. did not had any authority on the Jews till the Maccabean period.

hhmmm… why is “Don’t get caught” missing from the list?

Watch out for your enemies, flee enmity, know your opportunity. Most others contradict that sentiment though. Not all of these are ideal. For example, above flee enmity it says do away with enmity, but how can you do both?

A detail I did not include in my post addresses your reasonable question. It relates to the difference between a (real) law and a maxim. Michael Gmirkin referenced a work by Michael Gagarin, Early Greek Law (1989), and I quote the section that answers your question — to cut to the chase go to the bits in bold type, especially footnote #11:

And the footnotes of most interest (to me):

Prose helps memorization since most people weren’t literate.

I do not see any serious contradiction and as Neil wrote : ” Oikonomides writes that he wants his translation to be shared along with the note that other translations are possible and valid”

In your example enmity is απεχθεια, this can be translated also as hatred. In fact Liddel and Scott Lexicon gives this translation (hatred).

The ” Watch out for your enemies” can be translated as ” defend yourself from your enemies”

The word αμυνου which was used in Oikonomides translation for “watch out” come from αμυνα which means defense.

“Know your opportunity” which by the way I do not understand why you mention it, can be translated as “Know what is happening in your time”.

If you found any further contradiction I would be more than happy to discuss it with you.

The contradiction is between the line 112 Do away with enmities and line 116 Flee enmity.

“Know your opportunity” which by the way I do not understand why you mention it, can be translated as “Know what is happening in your time”.

People get caught because they are careless, not attentive. For example, if you wait until after a security guard passes before trying to break into a building, that is the opportunity, the right time, but trying to break in first then the security guard comes upon you, you get caught. The security guard in this case is your “enemy” which you are defending yourself from by dodging his patrol route.

I think that those two are not contradictory but complimentary.

112 can be translated as “Dissolve enmities”

and

116 as “Shun enmity” or “Shrink from doing enmity”.

I used the Liddel and Scott Lexicon for those translations, for example you can see flee (φευγε < φευγω) here :

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/morph?l=feu%3Dge&la=greek#lexicon

Α.I. 4. shun or shrink from doing.

As for the one I gave for “Know your opportunity” I mean the “Know what is happening in your time” now that I see it again I think more proper English is to render it to "Know what is happening in our times".

Keep in mind that Oikonomides' translations are 100% valid, the problem we have here seems to me that emanates from the fact that he created the article to "be reproduced in any number of copies necessary for a class in ancient Greek". I mention this cause I believe his priority was to rendered the words in the most common translations and not to the best non-contradictive way to be used by the English-speakers.

On the other hand I may just far-fetching here and Neil's observation, through Gagarin, can be applied here too.

The Romans may have recognized that they were becoming too Hellenistic and tried to make it seem like some of the Greek culture they were stealing could be misplaced onto another culture and misdated much earlier. I had long suspected that the Hebrew Bible was mostly written after the Persian conquest, but now after the Greek conquest seems more accurate. The influence of Roman shame of their own lack of culture, especially after the diaspora, may have played a role in reinforcing both Jewish and Christian culture resulting from downplaying Greek culture.

You may have something there as both the Old, the Septuagint and New Testament were first written down only from mostly from the third c BCE to the first CE by Hellenised Jews.

That is over a relatively short historical period of approximately four centuries which was the culmination of Hellenism as it flourished in the Middle East up to and including its manifestation within Roman Empire.

I’ve read that early on the ten words were covenantal or contractual. Each of the two tablets probably were identical; each having ten words—one copy for YHWH and one for the people. Both copies were fabled to have been kept in a secure coffer. The anecdote about Uzzah dying for stabilizing the ark, reinforced the concept of YHWH insuring safe custody for the divine/human agreements.

It seems that Gmirkin might say that with their growing awareness of the Hellenists that works like “Jeremiah” (i.e. 3.16, on remembering the ark no more & 36.36, on a new covenant replacement) would try to match the Greeks’ superior notions.

Well of course Yahweh got a copy, you can’t expect the omnipotent ruler of the universe to remember things.

The actual authors didn’t have Latin available yet so they were a bit confused over the distinction between omnipotence and omniscience. But seriously, the writers had God stipulating two tablets to keep things legal. Maybe his subjects felt more comfortable that way. After all, some Gods had proven forgetful.

Ex 2:24

God heard their groaning, and God remembered his covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Is 62. 6-7

You who remind the Lord,

take no rest

and give him no rest

until he establishes Jerusalem

Ps 119.49-50

Remember your word to your servant,

for you have given me hope.

My comfort in my suffering is this:

Your promise preserves my life.

Before getting too set on any particular meanings, best to keep in mind Oikonomides’ caveat (pp. 69-73):

I haven’t looked into the question of whether the OT was influenced by Greek culture beyond what I’ve read about it over the years on your blog. And I don’t know if it’s already been addressed, but, in the big picture, what I’m wondering in this scenario is how did the Maccabees come to accept the OT while at the same time being anti-Hellenistic.

Good point. I have addressed that question in another post, or other online discussion. Give me time to dig out the references so that when I reply it is not just me winging it from memory.

You may as well ask how they came to accept the OT which were derived from Babylonian.

The OT is anti-Hellenistic in many respects. For example, one god, no idols, circumcision and etc.

Maccabees accepted it cause those books presented a theocratic system, Josephus identified this phenomenon of the OT(Josephus Apion 2.165).

The book of Daniel was written around their time.

The response I hoped to present is proving to require more work than I anticipated. I have Hengel and others with me, but need to follow up a range of critical reviews of Hengel’s work (negative, positive and corrective) to make the comment current.

In very brief in the meantime — The Hellenism within Judea/Jehud is argued as being widespread prior to the Maccabean revolt, and the revolt made relatively little difference in the long-run to that Hellenistic cultural landscape. Recall that Plato’s ideal did include, iirc, a kind of monotheism, strict morality, even markers of separation from other people. In one sense, the Maccabees can be said to have been another “Hellenistic faction” that took on board with utmost seriousness certain details (and they added some of their own) that in fact originated with Plato’s ideal and myth of persuasion of the antiquity and divine origin of their laws. To that extent, the Maccabean revolt can be seen as a war between two Hellenistic factions, although the Maccabees themselves failed to recognize this, of course — the myths Plato wanted to instil had indeed taken hold.

But I am speaking now along lines I initially said I did not want to speak until I gathered sources that I have not touched now for some years. I may well find I have to revise what I wrote in the previous paragraph when I get all my stuff together.

Of course Russell Gmirkin will have his own response. I am not speaking for him, only my own view.

Conversely, I wonder why Hellenistic Jews (at least according to the Maccabee books) rejected the OT (or at least the Torah) if it was a product of Greek culture, e.g., 1 Mac. 1:11-15:

“In those days lawless men came forth from Israel, and misled many, saying, ‘Let us go and make a covenant with the Gentiles round about us, for since we separated from them many evils have come upon us.’ This proposal pleased them, and some of the people eagerly went to the king. He authorized them to observe the ordinances of the Gentiles. So they built a gymnasium in Jerusalem, according to Gentile custom, and removed the marks of circumcision, and abandoned the holy covenant. They joined with the Gentiles and sold themselves to do evil.”

Keep in mind that in Laws Plato wrote that the people in the new colony need to be taught that their laws are of divine origin.

The Pentateuch presents Israel’s laws as having a divine origin. They come direct from God on Mount Sinai. The Maccabees — a full hundred years after the composition of the Pentateuch according to Gmirkin’s thesis — fully believe that their laws did come from God and not from scribes sitting in a library at Alexandria reading Plato.

It is a tragic tale, but Plato’s visions of an ideal society (not only in Laws, but also/especially in Republic) have been the historical “philosophical source” of a line of values and concepts that have spawned totalitarian regimes. Plato taught total censorship, control of the masses by an “all-wise, all powerful” minority, total re-education in myths (lying propaganda) that would serve the power of the elites and total cohesion of the state. Dissidence was not to be tolerated.

That’s the “ideal” of the “kingdom of God”.

On people in a new colony: KINEAS AND HIS TEMENOS: AI KHANOUM AND DELPHI? https://www.academia.edu/1489675/_The_Founder_Shrine_and_the_Foundation_of_Ai_Khanoum_

Looking here at the Greco-Bactrian Demetrius [died circa 180 BC] I wonder why the high priest in Jerusalem wasn’t also wearing a elephant scalp headress: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/d2/Demetrius_I_portrait.jpg

Syria and Iraq once had Elephants. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Syrian_elephant Hippos lasted several centuries longer in some of the swamps along sections of the Orontes not far from Antioch.

The 10 Commandments were supposedly given in the 14 century bc. The Delphic Maxims around the 6th century bc. Couldn’t the Greeks have simply expanded on them? An 8 century difference is a very long time.

I don’t know of any evidence that would support Greek literature and ideas being influenced by Hebrew texts.

On the other hand, we do have evidence for ideas moving from the Greek world to the Jewish writers.

Russell Gmirkin is writing in the tradition of scholars who argue that the biblical texts were produced as late as the fifth, fourth and even third centuries bce. I agree with that view because it derives from valid historical methods of research. See, for example, Bible – History or Story?

I am happy to discuss further and point to other sources online if interested.

After I wrote my note I did some searching and found that, unlike 1400 century BCE, most scholars think the Pentateuch was written around 600 BCE. So I hope Gmirkin is correct about the 10 commandments being influenced by the Delphic maxims. More for me to work with while arguing/discussing with my Christian friends. But the discussion/arguments are quite worthless because the bible is so deeply entrenched in them no amount of evidence will make one bit of difference. Thanks for your reply.

Most biblical scholars seem to believe Jesus is still alive so and certainly most believe in a God of some sort so what “most scholars think” is hardly a commendation in my books 🙂

Yes, most have long taken the Babylonian Captivity as the time of the composition of the Pentateuch (ca 600 BCE) but see what Philip Davies has to say about such a notion: http://www.vridar.info/bibarch/arch/davies3.htm

I agree about the biblical scholars but I read about the date of the Pentateuch being around 600 BCE from Wikipedia so I felt that was probably in the ballpark.

Thanks for the links and Phillip Davies. I read most of the pages there. Still in the process of finishing. I just read most of “The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel” before I got bored. But the authors seem to agree that David and Solomon probably existed just on a much smaller scale. You seem to think that Davies is very reliable, I presume? Will check him out further.

Something not mentioned here is that Demetrius of Phalerum is alleged to had compiled the “Sayings of the Seven Wise Men” (Stobaeus Anthology 3.1.172) see : “The Regime of Demetrius of Phalerum in Athens, 317–307 BCE: A Philosopher in Politics” p. 95

This brings us closer to Alexandria and 270 b.c.