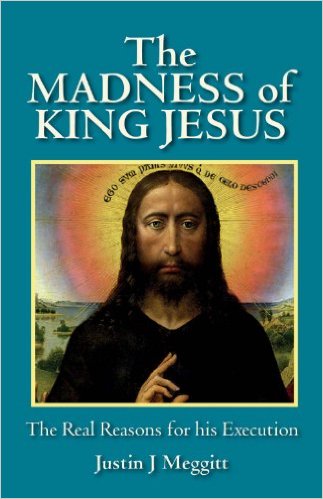

H/t a BCHF thread: A book due out in a few months from now, The Madness of King Jesus: The Real Reasons for His Execution by Justin Meggitt.

Given the understanding that the crucifixion of Jesus is “one of the most secure facts” we have in history Justin Meggitt tackles one of the perplexing conundrums that the crucifixion has left us: why did Pilate crucify Jesus yet not lift a finger against his followers, even allowing them to continue preaching about Jesus after his execution?

Some of us will be familiar with Paula Fredriksen’s answer to this question in Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews. Fredriksen’s argument is that Pilate knew Jesus was harmless — he had, according to the Gospel of John, travelled to Jerusalem for several years running where he preached quite harmlessly. For some reason on that last journey, however, the crowd got out of hand in their response to his preaching about the coming kingdom, and Pilate needed to nip in the bud early signs of trouble. Jesus was the one they were agitated over, so a quick crucifixion solved the problem. The disciples were of no account according to this equation.

Meggitt explains his confidence in the historicity of the crucifixion on page 380:

- multiple attestation in earliest Christian and non-Christian sources (Josephus, Tacitus);

- the absence of doubt by any of the early critics of the new religion;

- and “it is hard to imagine anyone in the early church would have wanted to fabricate [such a datum] about their founder”

These points (based on criteria of authenticity; an ideologically framed chronology; and the appeal to incredulity) are virtual mantras that are too rarely seriously questioned.

Another scholar, Fernando Bermejo-Rubio, in a 2013 article in the Journal for the Study of the New Testament, “(Why) Was Jesus the Galilean Crucified Alone? Solving a False Conundrum”, resolves the dilemma by denying that Jesus was crucified alone but was indeed crucified with followers:

The view that those crucified with Jesus had nothing to do with him is not only exceedingly improbable from a historical standpoint, but it uncritically relies upon the story told in biased sources: only the theological necessity to distance Jesus from any rebellious connection can account for the tenacity with which this view is held.

Meggitt proposes a different solution. The book is not yet published but he has had an article on the same theme published in the same journal in 2007 (JSNT 29.4: 379-413), “The Madness of King Jesus: Why was Jesus Put to Death, but his Followers were not?” The abstract:

To argue that Jesus of Nazareth was put to death by the Roman authorities because they believed him to be a royal pretender of some kind, fails to explain satisfactorily why he was killed but his followers were not. A possible solution to this conundrum, which is supported by neglected contextual data, is that the Romans thought Jesus of Nazareth to be a deranged and deluded lunatic.

The first part of the article outlines the evidence that it was standard practice for Roman rulers to pursue and execute followers of would-be insurrectionists along with their leaders.

For example, we know of the rebels Theudas and “the Egyptian” from both Acts and Josephus and that the Romans made a point of executing largasse numbers of their followers. Similarly (from Josephus) Pilate executed the followers of a Samaritan prophet. Ditto for the followers of Simon of Perea in 4 BCE.

Indeed, if we throw our net a little more widely, we find the same pattern of behaviour by the Roman authorities when faced with comparable leaders and movements elsewhere. For example, in the case of the slave king Eunus-Antiochus, the wonder-working Syrian who claimed that Atargatis-Astarte had promised him a crown, or Tacfarinas the charismatic north African rebel leader (Tacitus, Annals 2–4), or Mariccus, the Gallic god-man (Tacitus, Histories 2.61), or the insurgent general Anicetus of Pontus (Tacitus, Histories 3.48-49), the common practice seems to have been that not only would a seditious leader be killed (if caught), but his followers, or at least those prominent amongst them, would be executed or enslaved. Indeed, the killing of bandit leaders and their associates was something played out again and again in the Laureolus. In this notorious and hugely popular mime (Gaius apparently saw it on the day of his assassination) it was not unusual to have condemned men play the victims, and the stage and audience were often literally awash with blood. (p. 382)

Most New Testament scholars seem to accept that Jesus was crucified on the charge of being a royal pretender and a few have attempted to explain why, this being the case, his followers were ignored. Meggitt reminds us that Sanders, for example, thinks that Pilate was only acting under pressure from the Jewish priests whose problem was Jesus alone. But however one attempts to explain the lack of interest in the disciples, the fact remains (says Meggitt) that Pilate was said to be acting contrary to the way Roman governors usually acted and against his own nature in particular.

We know the Gospels tell us that the family of Jesus thought him mad (Mark 3:19-21); that others believed him to be possessed (Mark 3:22; Matthew 12:24; Luke 11:14; John 8:48). The Gospel of John implies that some thought Jesus to be suicidal (John 8:22), and elsewhere he is said to be a drunkard and a false prophet. These latter characteristics may not necessarily indicate insanity but they could without difficulty be associated with it.

Meggitt next undertakes a lengthy discussion of the evidence for how the ancients understood madness, how those deemed insane were treated, and so forth. This informative discussion leads eventually to two case studies of special relevance to Jesus: the case of Carabas in Philo’s Flaccus and that of Jesus ben Ananias in Josephus’s Jewish War.

Carabas the mock-king

Meggitt provides a translation of the relevant passage in Philo:

(36) There was a certain lunatic named Carabas, whose madness was not of the fierce and savage kind, which is dangerous both to the madmen themselves and those who approach them, but of the easy-going, gentler sort. He spent day and night in the streets naked, shunning neither heat nor cold, made game of by children and the lads who were idling about.

(37) The rioters drove the poor fellow into the gymnasium and set him up on high to be seen of all and put on his head a sheet of byblus spread out wide for a diadem, clothed the rest of his body with a rug for a royal robe, while someone who had noticed a piece of the native papyrus thrown away in the road gave it to him for his sceptre.

(38) And when as in some theatrical farce he had received the insignia of kingship and had been tricked out as a king, young men carrying rods on their shoulders as spear- men stood on either side of him in imitation of a bodyguard. Then others approached him, some pretending to salute him, others to sue for justice, others to consult on state affairs. (39) Then from the multitudes standing round him there rang out a tremendous shout hailing him as ‘Marin’, which is said to be the name for ‘lord’ in Syria (Colson LCL).

Jesus ben Ananias

(300) But a further portent was even more alarming. Four years before the war, when the city was enjoying profound peace and prosperity, there came to the feast at which it is the custom of all Jews to erect tabernacles to God

(301), one Jesus, son of Ananias, a rude peasant who, standing in the temple, suddenly began to cry out, ‘A voice from the east, a voice from the west, a voice from the four winds; a voice against Jerusalem and the sanctuary, a voice against the bridegroom and the bride, a voice against all the people’. Day and night he went about

(302) all the alleys with this cry on his lips. Some of the leading citizens, incensed at these ill-omened words, arrested the fellow and severely chastised him.

(303) But he, without a word on his own behalf or for the private ear of those who smote him, only continued his cries as before. Thereupon, the magistrates, supposing, as was indeed the case, that the man was under some supernatural impulse, brought him before the Roman governor;

(304) there, although flayed to the bone with scourges, he neither sued for mercy nor shed a tear, but merely introducing the most mournful of variations into his ejaculation, responded to each stroke with ‘Woe to Jerusalem!’

(305) When Albinus, the governor, asked him who and whence he was and why he uttered these cries, he answered him never a word, but unceasingly reiterated his dirge over the city, until

(306) Albinus pronounced him a maniac and let him go (Thackeray LCL).

I have posted T. Weeden’s parallels elsewhere. Meggitt adds the list from Craig Evans, Jesus and His Contemporaries (my formatting):

<

div class=”page” title=”Page 22″>

<

div class=”layoutArea”>

<

div class=”column”>

- Both entered the precincts of the Temple (Mark 11.11, 15, 27, 12.35, 13.1, 14.49; JW 6.5.3)

- at the time of a religious festival (Mk 14.2, 15.6, Jn 2.23; JW. 6.5.3).

- Both spoke of the doom of Jerusalem (Lk. 19.41-22, 21.20-24; JW 6.5.3),

- the Sanctuary (Mk 3.2, 14.58; JW 6.5.3.301),

- and the people (Mk 13.17; Lk. 19.44; 23.28-31; JW 6.5.3.301).

- Both apparently alluded to Jeremiah 7, where the prophet condemned the Temple establishment of his day (‘cave of robbers’: Jer. 7.11 in Mk 11.17;

- ‘the voice against the bridegroom and the bride’; Jer.7.34 in JW. 6.5.3.301.

- Both were ‘arrested’ by the authority of the Jewish—not the Roman—leaders (Mk 14.48; Jn 18.12; JW 6.5.3.302).

- Both were beaten by the Jewish authorities (Mt. 26.68; Mk 14.65; JW 6.5.3.302).

- Both were handed over to the Roman governor (Lk. 23.1; JW 6.5.3.303).

- Both were interrogated by the Roman governor (Mk 15.4; JW 6.5.3.305).

- Both were scourged by the governor (Jn 19.1; JW 6.5.3.304).

- Governor Pilate may have offered to release Jesus of Nazareth, but did not; Governor Albinus did release Jesus son of Ananias (Mk 15.9; JW 6.5.3.305).

The similarities between these two figures and Jesus are transparent. But, especially in the case of Carrabbas, their reputed insanity is not so often remarked upon — perhaps because scholars fail to recognize that trait as having relevance to Jesus. Meggitt suggests otherwise. Here is his comment on Jesus ben Ananias:

According to Josephus, ben Ananias displayed behaviour typical of the mad when he appeared before the governor: he showed no regard either for his own life (failing to ask for mercy nor complaining ‘despite being flayed to the bone’) or for those around him (he failed to answer Albinus’s questions, merely repeating his oracle, not saying who he was, or where he was from or why he making this pronouncement).57

And the footnote adds to the point:

57. For examples of the insane’s lack of concern for their own lives, see Aretaeus, Causes and Symptoms of Chronic Diseases 1.5, 6; Horace, Art of Poetry 462-63; Mk 5.5. For their failure to communicate meaningfully with those around them, see Celsus, De Medicina 3.18.11; Caelius Aurelianus, Chronic Diseases 1.148.

Of course we think here of Jesus before Pilate. He appeared not to care that he was facing crucifixion; he answered cryptically or not at all.

The difference with Jesus

The significant difference between Carrabbas and Jesus ben Ananias on the one hand and Jesus of Nazareth on the other is that the former two were dismissed. They were not executed, let alone crucified, for being mad.

Meggitt’s response to this anomaly is to call to remembrance the Temple incident. There we see Jesus breaking out with violence.

From a Roman point of view, Jesus’ actions in the Temple would be most easily understood as the anti-social, erratic ragings of a particular kind of lone madman, the kind that is not released, unfettered (as was the case with ben Ananias) to roam the streets, but who had to be dealt with. Even if Jesus had not displayed such aggression before, which is not necessarily the case, he could easily fall into this category and be judged one of those who despite ‘showing the most complete appearance of sanity whilst seizing occasion for mischief… are detected by the result of their acts’ (Celsus, De Medicina 1.183-84).

The belief that Jesus was just such a madman was probably already in circulation during his ministry, and it is always possible that this reputation preceded him. The tradition in Mk 3.19b-21 is hardly one that the early church would have invented and, for our purposes, it is important to note that it tells us that his family sought to restrain him, a sign that his mania was considered particularly severe.

Indeed, perhaps, as Sanders (1993: 153) speculates, this tradition might be ‘a remnant of a once larger body of material that depicted Jesus as engaging in erratic behaviour’.

Jesus’ age might also have encouraged such a judgment by Pilate. According to Caelius Aurelianus, ‘Mania occurs most frequently in young and middle-aged men, rarely in old men, and most infrequently in children and women’. In addition, Jesus did not show signs of the dissociative euphoria associated with the ‘gentler’ kind of madness and so he is more likely to have been thought more seriously disturbed. (pp. 401-402, my formatting)

This is, of course, speculative — not the “not necessarily”, “could”, “probably” and “possibly” and the “might” and the “likely” . . . But this is standard argument when it comes to exploring the “historical Jesus”. That is, Meggitt’s thesis is perhaps no less secure than many others’. The key factor in its favour, I suspect Meggitt would claim, is its explanatory power. Does it make more sense of “the evidence” than other scenarios that generally leave the disciples untroubled by Pilate. (I place “the evidence” in quotation marks because I think there are other methodological difficulties with taking the narrative details as historically secure in the absence of external corroboration. But all that is another story.)

If, as seems likely, the historical Jesus did proclaim something about the arrival of the kingdom of God and believed himself and the Twelve to have some part in it, but did not think of himself as somehow establishing this by force of arms, it would be perfectly reasonable for Pilate to assume that he was, in some sense, delusional. The fact that he probably maintained that his Kingdom was already present, despite the lack of material evidence, would surely have reinforced this diagnosis. From a Roman point of view would Jesus of Nazareth really appear much different from cases of delusion typical of common forms of mania? From people who believed themselves to be Atlas, bearing the world on their shoulders or some other god (Galen 8.190 K)? . . . . (p. 403)

Then again, recall Carrabbas and the close association between mock royalty and insanity. . .

<

blockquote>The likelihood that Jesus was perceived to be insane is also indicated in the details of his execution. Although the mocking of Jesus as a king might well have come naturally to the auxiliaries if they knew about the specific kingly claims made by or about Jesus, we should not overlook the possibility that their preoccupation with Jesus’ kingship might come directly from the fact that kingship was often closely associated with the insane—that association could be reason enough to explain the form that the mockery took. We have already noted that the closest parallels to the mocking of Jesus (Mt. 27.27-3; Mk 15.16-20; and also Jn 19.1-3) are found in the treatment of the madman Carabas, who was, of course, arrayed as a king. Most ‘temporary kings’ in antiquity, such as the unfortunate Carabas or those given this role in the Saturnalia, were insane or expected to act the part of the madman . . .

Indeed, the crucifixion between two ‘brigands’, who may well have functioned as a macabre royal retinue reminiscent of the mock guards on either side of Carabas during his pretend enthronement, and the titulus itself might not be intended to tell onlookers of Jesus’ crime of sedition but rather to function as a comic graffito, a shorthand way of conveying the idea that the man on the cross was self-evidently delusional. . . . (p. 404)

Flogging was also associated with the mad, and wine (given to Jesus on the cross) was said to be a cure.

Questions and tentative answers

One does wonder, however, if such a view of Jesus could account for Jesus being clearly thought sane enough by enough others to gather a serious following. It’s hard to imagine Carrabbas or Jesus ben Ananias having a band of loyal followers. Meggitt’s answer is that the mad were said to exhibit a broad range of behaviours. They could appear quite rational for lengthy spans of time.

Meggitt has proposed an explanation for Pilate ignoring the followers of Jesus but in doing so has left another question — by his own admission — somewhat open. Why would Pilate have crucified a madman? Meggitt modestly admit he cannot be dogmatic. However, his exploration into beliefs about and accounts of insanity in the ancient world (details that I have bypassed in this post), leaves him to conclude:

As I said at the outset of this piece, we may never know why Jesus died, but we can say that, if he were thought a dangerous, deluded madman, his death is all the more unsurprising. . . .

We may not be able to say why Jesus was killed, but we can rule this explanation out.

However, if Jesus of Nazareth was believed by Pilate and his troops to be a worthless, dangerous and disruptive madman, as I have maintained here, we would have found a Jesus that would fit the bill—only he, and not his followers, would have been killed. If this Jesus is not one that resembles the historical Jesus’ own self-understanding, or the Jesus proclaimed by his followers, that is to be expected and supports rather than undermines the plausibility of this thesis . . . (pp. 406-7, my formatting)

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Very intriguing hypothesis! It is also very interesting about the parallel case.

So in the question about ‘Lord, Liar, Lunatic, or Legend?’ this chooses the ‘lunatic’ option.

Mark says that when Jesus was arrested ALL the disciples fled. Maybe they weren’t arrested because they got away.

That there was evidently no serious attempt to arrest them as well along with Jesus and then the fact that they appear to have been free to call for devotion to Jesus in ensuing months is the problem that is created by the common argument that Jesus was crucified as a threat to the political order.

Why would the disciples have fled except for the fact that they thought they were going to be arrested?

It’s a narrative created by the author and requires discussion at the literary level. It is evidently to fulfil the prophecies that Christ is to be deserted by his followers.

If we were to take it as a serious historical report then we must be left wondering at the incompetence of the authorities. Had they never attempted to arrest a band of men all congregating in one place before? If they were serious would they just waltz up in he naive hope that they’ll all stay put while they are all bound and taken away? And then we read only weeks later they are all out and about in public preaching about Jesus without any attempt to catch them even then. But it’s not a historical report and the historical authorities are not therefore left embarrassed in reality.

If Jesus never existed at all, then he didn’t die for any reason. We cannot have our mythical cake and eat it.

The personality described in the Gospels, however, seems extremely sharp intellectually, especially in his witty repartee. Of course, he may also have held misguided views about his own religious destiny or identity that some would regard as mentally ill, possibly by his own family on one occasion (although this has been questioned here). (I am trying to persuade an ex-Methodist minister friend with degrees in psychology to finish a “clinical” study of the unusual mentality of Jesus before we are both committed to the Great Asylum in the Sky.)

But how “mad” are egocentric mystics? How “mad” was Swedenborg or Baha’u’llah or Joan of Arc or Timothy Leary – or Hitler? Are there compartments in some “minds” that serve separate functions, as with some sex criminals?

Is religion itself a collective insanity – because, if so, there have been a lot of crazy people about, from Thomas Aquinas to Alasdair MacIntyre? Was it Jung who said that people who pray to God are regarded as normal, but if they quote his replies, they are considered a bit nuts?

The question is not mythicism versus “historicism” but understanding Christian origins and that means understanding the Gospels among other things. Of course Jesus, whether figurative, historical, theological, was executed for a reason.

Jesus *portrayed as executed* for a reason …

The very fact that he had followers would argue for their censure in some form, regardless of what was judged to be the nature of his deviance.

On another forum there was some talk that Josephus and Philo of Alexandria never mention crucifixions during the time of Pilate, though they do mention people being “put to the sword.” Crucifixions are mentioned much later. Maybe during the 70 A.D sacking of Jerusalem, and definately during the Bar Kohkba revolt. Of course, this also argues for later Gospel authorship. Anyone else know anything about this.(I think the Gospels are complete fiction, anyway, so that’s the way I lean.)

Clarke Owens addresses this question in his book, Son of Yahweh. See http://vridar.org/2014/02/19/constructing-jesus-and-the-gospels-how-and-why/

Josephus mentions 2,000 crucified by Varus, around 4BC.

… but then does not seem to record any crucifixions from then (or maybe ~4AD/CE) until the late 40s AD/CE.

I have added a correction to the original post this morning. Last night I overlooked Meggitt’s explanation for taking the crucifixion of Jesus as effective historical certainty and have since added them near the top of the post.

Would the reason(s) for the execution of Jesus differ, if he really existed or if he was a totally imaginary person? What understanding in reference to this most important “fact[oid]” in Christian origins can we reach, or has been reached, with such “certainty” as for example that the early chapters of Acts are entirely fictional?

Discarding “Josephus” and “Tacitus”, we have almost only the NT to go on for any “forensic” explanation of the crucifixion story and possible alternatives to explain its existence. I understand that Clarke Owens sees it as an allegory for the destruction of Jewish culture in 70 CE, but there are range of different explanations as to why a real person might have been executed by real people; and one can only list them, I suppose, in order of informed plausibility.

The case for Mark using Homer is quite strong. Only one thing we must never do, it seems, is to accept that the core of the gospel narrative could be true!

Sometimes important human lives actually fit a “tragic” dramatic narrative. That adds to their longevity in collective imagination. I wonder what Shakespeare would have made of Kennedy or Hitler?

There’s no drive to “not accept that the core of the gospel narrative could be true”. The arguments I present are not about “disproving the Bible” or “undermining Christianity” but simply with treating the question of Christian origins in the same way historians (as distinct from theologians, generally) approach evidence when addressing any other historical question. Traditional biblical scholarship makes ideological assumptions — after all, Christianity is said to be a “historical faith” in that God entered history through Jesus — and use ad hoc rationalizations to argue for the historicity of the core of the gospels. Historians elsewhere use no such ad hoc rationalizations but tediously rely upon external corroboration, and secure data about provenance of sources, etc., before they jump in the deep waters of “belief” that “the core” might be historical.

“treating the question of Christian origins in the same way…”

Such a simple concept. So often misunderstood or under-appreciated. Thanks.

No objection to that approach.

However, it surely makes a difference to any plausible historical explanation of Christian origins if we hypothesize that there was a real gifted person (or maybe several) who was executed, at their first-century inception, rather than that he was entirely an imaginative retrospective confection by some gifted second-century equivalents of Henryk Sinkiewicz, C. S. Lewis and Lloyd C. Douglas.

I don’t know of any historian who uses that approach. All that I have read about how historians work and of all the historical works I have read — all of this tells me that historians limit their questions according to the ability of the evidence to answer them. Hence ancient historians generally explore much more general questions than modern historians simply because they don’t have the same amount of data to enable them to sensibly ask for the same sorts of details.

The only authors who use hypotheses about a particular person or persons intervening to inaugurate something in the remote past are theologians and cranks like von Daniken or other conspiracy theorists.

No need to hypothesize David. Josephus relates the stories of several first-century messianic Jewish figures, some of great reknown (like John the Baptist), whose stories share many similarities to the Jesus of the Gospels. In the case of John, his story has even been folded into the Jesus narrative (although I suspect this was a play by Christians to expand their base of followers).

We know in some cases, and can be justifiably suspicious in others, that Jesus’s life was embellished with details from the lives of others, real or mythical (John the Baptist, Romulus, Moses, Joshua, Elijah, possibly even Josephus’s “the Egyptian”). The question of historicity is one of identity. Was there a man named Jesus who was the SAME man that spawned the Christian sect who was the SAME man later worshipped as a God? The Jesus of the Gospels being simply a pastiche of the lives of several other (historical) people to serve a theological purpose would be a demonstration of myth, not history.

Nothing intrinsically impossible even in the ancient world about someone inaugurating something religious or political. It has nothing to do with an actual UFO or visible dove from the heavens, &c.

I addressed this issue in my book “The Judas Brief.” The basic argument of the book is that Judas negotiated a three-way agreement among Pilate, the High Priest and Jesus, in which Jesus agreed to remain under house arrest with the High Priest as a guarantee that his followers would remain quiet during the Festival. After the holiday Jesus was to be freed. BUT, Herod Antipas wanted Jesus dead because he was a problem like John the Baptist, and successfully pressured Pilate to break the agreement.

What was the leverage Antipas exercised on Pilate?

Interesting, but absent actual independent evidence, all we have here is what specialists in other mythologies call “retconning”: justifying errors or oversights with elaborate, post hoc explanations to harmonize the error with the universe. A classic example is the use of “parsec” in Star Wars: you can play with the dialogue to make the usage fit in context, but the real explanation is that George Lucas simply didn’t know what the word meant and used it wrongly.

We can retcon the crucifixion story all we want, but any such story is inherently less likely than the assumption that the fictionalization was simply inelegant, because the latter requires no ad hoc assumptions whereas the former does.

For a similar hypothesis, see this essay:

https://rogerviklund.wordpress.com/2011/08/15/the-traditional-translation-and-interpretation-of-the-last-supper-betrayal-of-the-original-text/

It proposes that Judas acted as go between to hand Jesus over to the priests. The actual betrayal occurred when instead of trying Jesus under Judean law, the priests gave him to the Romans to be executed.

Neil,

The reason that the authorities did nothing to hunt down Jesus’ followers was the “resurrection”/empty tomb.

At that point, Jesus’ followers went from potential political insurrectionists to spiritual followers of a “risen” Jesus. They were much less of a threat and hardly worth pursuing.

Do you have evidence for this claim?

Does it not seem odd that the authorities did not decide to hunt down Jesus’ followers at the same time they sought out Jesus? Or that they continued to hunt them down from the time of Jesus’ arrest and the days following?

And when the followers said that the Jesus the authorities had crucified was not dead but still alive and with even greater power is it not odd that the authorities continued to ignore them?