Continuing from the previous post. . . .

Fallibility of eyewitness accounts

Eyewitness accounts are not necessarily more reliable than other sources. Timothy Good compiled 100 eyewitness accounts of the assassination of President Lincoln and its immediate aftermath in We Saw Lincoln Shot: One Hundred Eyewitness Accounts. David Henige comments in Historical Evidence and Argument (2005):df

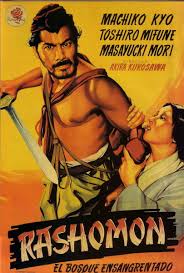

Reading these reminds us of the omnipresent Rashomon effect, and also that a secondary account that collects and evaluates a number of primary sources might actually be preferred to these, even when it paraphrases them, as long as it does this well, and as long as it allows access to all the evidence. (2005: 48 — Formatting and bolding mine in all quotations)

We have all heard of the studies that demonstrate the depressing unreliability of memories of events witnessed and experienced. Henige cites several articles addressing many of these studies and I attempted to follow up a few to flesh out details. One common theme is the way false memories can be implanted as a byproduct of others asking a witness questions that introduce the possibility of details that were not originally seen (e.g. Wells and Olson).

Here are a few pertinent sections from Toward a Psychology of Memory Accuracy by Goldsmith, Koriat and Pansky:

- Although thinking about a perceived event after it has happened helps maintain its visual details, thinking about imagined events also increases their vividness, and may therefore result in impaired reality monitoring for these events (Suengas & Johnson 1988). Goff & Roediger (1998) found that the more times subjects imagined an unperformed action, the more likely they were to recollect having performed it. . . . .

- The fact that people know at one time that a certain piece of information was imagined, dreamt, or fictional does not prevent them from later attributing it to reality (Durso & Johnson 1980, Finke et al 1988, Johnson et al 1984). . . . ;

- In comparing the results for an immediate test with those for a test given two days later, the proportion of accurate recall declined over time, whereas false recall actually tended to increase (McDermott 1996).

Nor does the research support the belief that false memories are necessarily the product of trauma and psychological repression:

Many cognitive psychologists, however, doubt these assertions (Lindsay 1998, Loftus et al 1994), pointing instead to evidence suggesting that false memories may arise from normal reconstructive memory processes.

Henige’s conclusion:

We can hardly re-enact the life experiences of eyewitnesses from the past to judge their capacity with respect to memory. The alternative is to conduct large-scale and repeated experiments that test various kinds of memory. As noted, hundreds of these have been carried out and in general the results have not been encouraging for any historians who might wish to believe eyewitnesses implicitly.

Testis unus, testis nullus, One witness is no witness

Testis unus, testis nullus, runs the Roman legal dictum: “one witness [is] no witness.”

Or as a less exalted source [Granger, Shades of Murder] put it: “Unsubstantiated? It means that no other person than yourself has claimed to have witnessed these things or been able to show that they existed.” — (2005: 49)

In ancient history scholars can find themselves depending more often than not single sources for what they know. One would expect this difficulty to make historians more cautious about how they interpret and rely on this solitary pieces of data for various arguments but unfortunately the opposite is found to be the case far too often.

There is a natural tendency to treat unique evidence with kid gloves.22 (2005: 49)

Henige’s footnote no. 22 brings us to a biblical scholar as a negative example:

22 Or even attempt to turn it to advantage, as R.N. Whybray does when he writes: “[t]o regard as useless for the historian’s purposes the only account of a nation’s history written by its own nationals is, to say the least, extraordinary.” Whybray, “What Do We Know,” 72.

Naturally an “only find” does deserve preservation. No-one disputes its importance. However,

that fact by itself should persuade the historian to apply every form of internal criticism possible. (2005: 49)