Introduction

I’ll begin this post by acknowledging my debt to Earl Doherty. It was he who convinced me that the gospel Paul believed and preached was derived only from scripture and visions/revelations, and that it did not include a Son of God who lived a human life on earth. Doherty’s demonstration of those points in his The Jesus Puzzle and Jesus: Neither God Nor Man is, in my opinion, quite persuasive. And since some of his arguments for those contentions are available on Vridar (See part 19 of: Earl Doherty’s response to Bart Ehrman’s ‘Did Jesus Exist?’), I see no need to argue them further here. For this post I take as my point of departure that Paul did not believe in a Son of God who had wandered about Galilee and Judaea teaching and preaching, exorcizing demons, working miracles, and gathering disciples.

What the Son did do, according to Paul, was descend from heaven, get crucified by the rulers of the world (1 Cor. 2:8), and then rise back to his celestial home. But where did he believe the Son’s crucifixion had occurred? And what was his belief regarding how that event procured salvation for the faithful? And was there a particular scripture that led him to his core beliefs about the Son?

But where did he believe the Son’s crucifixion had occurred?

And what was his belief regarding how that event procured salvation for the faithful?

And was there a particular scripture that led him to his core beliefs about the Son?

.

My answers to these three questions are different from Doherty’s. He proposes that the crucifixion was believed to have taken place in “an unspecified spiritual dimension,” in a “dimension beyond earth,” or perhaps somewhere above the earth but below the moon (Jesus: Neither God Nor Man, p. 112). But I think it was believed to have taken place in Judaea. I see the Son’s descent for crucifixion as being a limited particular task like those performed by disguised divine personages and angels who descended to earth in other Old Testament and intertestamental literature, e.g., the incognito visit by heavenly figures to Abraham and Lot; the angel Raphael’s incognito mission in Tobit.

In regard to Paul’s soteriology, Doherty holds that at least the seven so-called undisputed Pauline letters were largely the work of one man, and so he apparently finds ways to explain to his own satisfaction the presence of varying soteriological teaching in them. I, on the other hand, have a serious problem with their inconsistences and think, as I have explained in posts two through six, that they have been heavily interpolated. And so in the letters I would disentangle the rescue and redemption soteriology of Simon/Paul from the sacrifice and atonement soteriology of a proto-orthodox interpolator.

Finally, Doherty, as a prominent part of his argument for locating the Son’s crucifixion in a sublunary heaven, has recourse to the Vision of Isaiah, i.e., chapters 6 – 11 of the Ascension of Isaiah (see pp. 119 – 126 of Jesus: Neither God Nor Man). I too think the Vision of Isaiah is key for understanding Christian origins. In fact, I go further and argue that it—in its original version—was already in existence by 30 CE and was—more than any other writing—the source of Simon/Paul’s gospel. But I am not convinced that it located the Son’s crucifixion somewhere other than Judaea.

| In this post and the next I am going to discuss the possibility that Simon/Paul derived his gospel initially from the Vision of Isaiah and that in its original form it possessed a Son of God who descended to Judaea for only a few hours.I suspect the Vision depicted a Son who, having repeatedly transfigured himself to descend undetected through the lower heavens, transfigured himself again upon arrival on earth so as to look like a man. Then, by means of yet another transfiguration, he surreptitiously switched places with a Jewish rebel who was being led away for crucifixion. All this was done by the Son in order to trick the rulers of this world into wrongfully killing him. |

.

Preliminaries

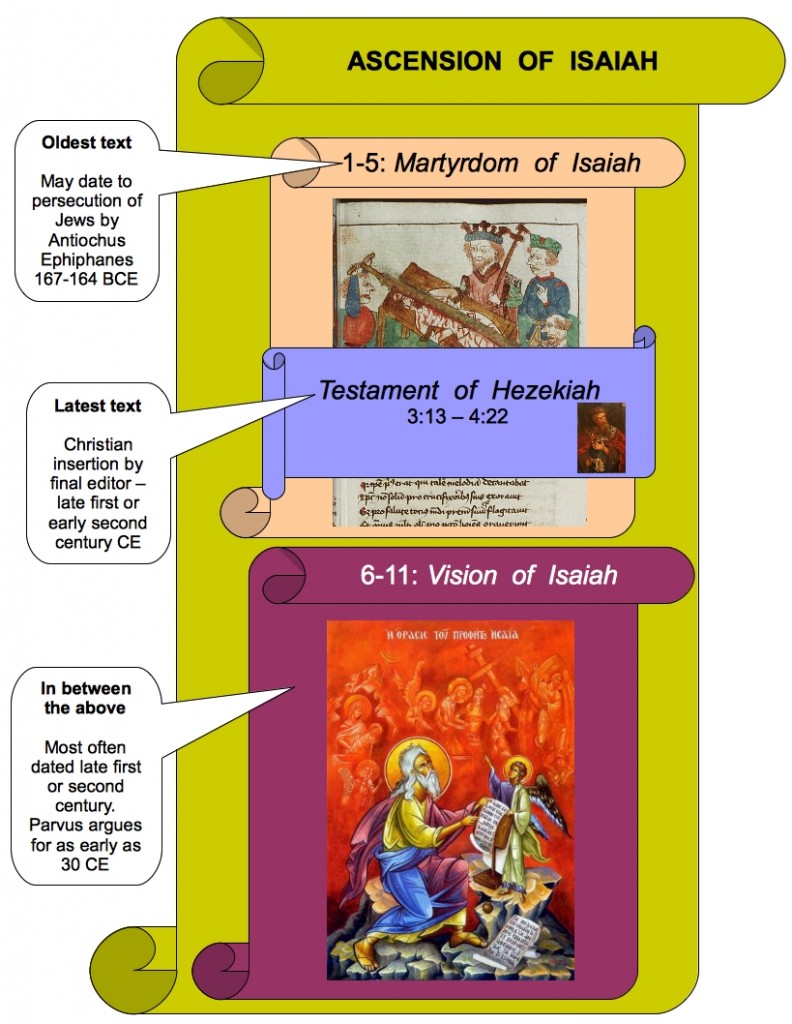

The Ascension of Isaiah is a composite work made up of at least two parts.

- The first, which consists of chapters 1-5, is usually referred to as the Martyrdom of Isaiah.

- The second, the Vision of Isaiah, consists of the remaining chapters and is known to have circulated independently.

The Martyrdom section itself is, in the opinion of many scholars, a composite work. It is thought that its oldest element (the story of Isaiah’s murder) is Jewish and that 3:13-4:22 is a Christian addition to it. Whoever made the insertion, however, did so with an awareness of the Vision, for “3:13 clearly alludes to chapters 6-11, and there are also a number of other links between 3:13-4:22 and the Vision” (M.A. Knibb, “Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by J.H. Charlesworth, p. 148). Finally, besides these three larger sections there are some short passages that may be the redactional work of the final editor who put the Ascension together.

Chronologically the Jewish source of the Martyrdom would be the earliest component of the Ascension, and may go back “ultimately to the period of the persecution of the Jews by Antiochus Epiphanes in 167-164 BC.” (Knibb. P. 149).

The latest component would be the 3:13-4:22 interpolation and, if it is also the work of the final redactor, probably dates sometime from the end of first century CE to the first decades of the second.

The dating of the third component, the Vision of Isaiah

The dating of the third component, the Vision of Isaiah, falls somewhere in between those two endpoints. Exactly where is debatable, for “[t]he criteria used are mostly indicative of a very approximate date” (R. Bauckham, “The Ascension of Isaiah: Genre, Unity and Date,” in The Fate of the Dead: Studies in Jewish and Christian Apocalypses, p. 381).

Most scholars date it to the end of the first century (e.g., R. H. Charles and, more recently, E. Norelli) or a few years later. Robert G. Hall too, while noting that “[t]he Vision of Isaiah is comparatively timeless,” is inclined to date it “from the end of the first century or the beginning of the second” (“The Ascension of Isaiah: Community Situation, Date, and Place in Early Christianity,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 109/2, 1990, p. 306).

| While I have no major problem with dating the 3:13-4:22 interpolation and the final compilation of the Ascension to the turn of the first century, I will argue in this post, that there are good reasons to think the composition of the Vision may have been as early as 30 CE. |

.

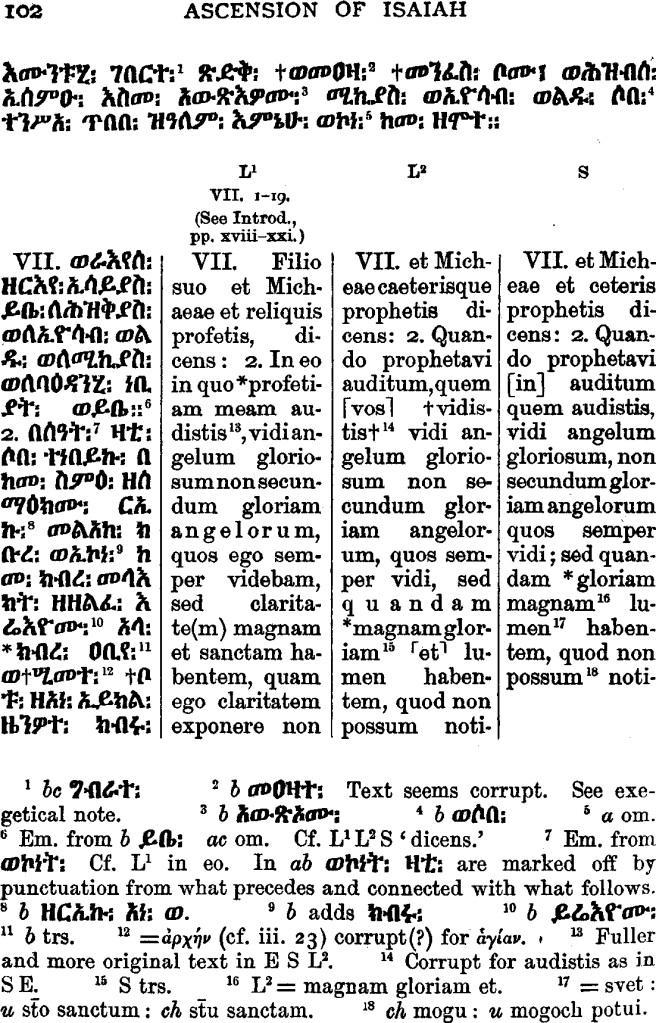

Scholars are in agreement that the original language of the Vision and the 3:13-4:22 section of the Martyrdom was Greek. The actual story of Isaiah’s murder too, though probably originally composed in Hebrew, was translated into Greek at an early stage. But only a fragment of the Greek text (G) of the Ascension has survived. To determine the original reading scholars are largely dependent on translations, some of which are in Ethiopic (E) and complete, and others in Latin (L1, L2) and Slavonic (S) and are partial. There is also a rather extensive Greek recasting of the Ascension called the Greek Legend (GL) that dates from the Middles Ages. Unfortunately, there are numerous and sometimes significant differences between the readings of these. Where pertinent in this post I will indicate which of the readings I am using.

.

The Vision in Brief

The Vision of Isaiah begins by relating that Isaiah, while at the court of King Hezekiah, was carried up in his mind to heaven and had a vision (chapter 6). Isaiah then describes his journey through the heavens accompanied by the angel who was sent to fetch him (chapters 7-8; it is from this journey that the title Ascension of Isaiah comes.) When he arrives in the seventh heaven (chapter 9) he sees all the righteous from the time of Adam onwards and the crowns and thrones that they will receive. He asks why they have not already received these. His angel guide replies:

They do not receive the crowns and thrones of glory… until the Beloved descends in the form in which you will see him descend. The Lord will indeed descend into the world in the last days… and become like you in form, and they will think that he is flesh and a man.

And the god of that world will stretch out his hand against the Son, and they will lay their hands upon him and hang him upon a tree, not knowing who he is.

And thus his descent, as you will see, will be concealed even from the heavens so that it will not be known who he is.

And when he has plundered the angel of death, he will ascend on the third day [L2 & S: And he will seize the prince of death, and will plunder him, and will crush all his powers, and will rise on the third day.]… And then many of the righteous will ascend with him, whose spirits do not receive (their) robes until the Lord ascends and they ascend with him. (9:12-18)

Isaiah is next shown the book that contains the things people have done in the world. Then he sees the Son and the Holy Spirit, and glimpses the glory of God the Father himself. After he has joined in the worship of these, he hears the Son receive a commission from God to descend to judge the princes of the world and then return in triumph:

Go out and descend through all the heavens. You shall be in the world, and go as far as the angel who is in hell. And you shall make your form like theirs. And they will not recognize you, nor will the angels and the princes of that world; and you will judge the prince of that world and his angels, and the rulers of the world. For they have denied me and said, ‘We alone are and there is no one besides us.’

And afterwards you shall not be transformed in each of the heavens, but in great glory you shall ascend and sit at my right hand. And then the princes and the powers and all the angels and all the rulers of heaven and earth and hell will worship you. (10:7-16, L2 version)

Isaiah then sees the Son carry out the commission (10:17-11:33). The vision completed, Isaiah says: “These things I have spoken. And the end of this world and all this vision will be brought about in the last generation” (11:37-38). The Vision ends with the words: “And Isaiah made him [Hezekiah] swear that he would not tell this to the people of Israel, and that he would not allow any man to copy these words. And then [i.e., in the last generation] they shall read them.”

(This rough summary does not include many of the smaller differences between the E/L1 and L2/S versions. Nor does it go into one very big difference that occurs in chapter 11. I will address that in the next post.)

|

Two passages that come across as so primitive that one can justifiably wonder: Could the Vision have been the original source of the gospel message? |

.

In the summary I have purposely spotlighted two passages that, to my mind, come across as so primitive that one can justifiably wonder: Could the Vision have been the original source of the gospel message?

Here in these passages the essential components of Simon/Paul’s gospel —the descent, crucifixion, and return to heaven— are present, and nothing is said about a teaching ministry by the Lord, or miracles that he will perform, or disciples that he will call to follow him.

The Christology is high.

The Lord is a divine being before his descent, but is exalted to an even higher level of divinity after he fulfills God’s command.

And, as Earl Doherty has noted, the Son’s mission is presented as “a simple rescue operation” (Jesus: Neither God Nor Man, p. 123), not as an atoning sacrifice for the sins of mankind.

| Polemics are a feature of practically every early Christian writing. Its absence from the Vision may be an indication that it dates before all of the others. |

.

The Vision of Isaiah is “very much at home in the worlds of Jewish apocalypticism, of early Christianity, and of early gnosticism” (R. G. Hall, “Isaiah’s Ascent to See the Beloved: An Ancient Jewish Source for the Ascension of Isaiah?,” Journal of Biblical Literature, 113/3, 1994, p. 470). But it is unusually free from polemics.

In contrast to the predictions in 3:13-4:22, there is no prophecy in the Vision about future opposition to it or to those who will believe it. To account for this Hall suggests that “[p]erhaps the group behind the Vision has not yet had to define itself over against other groups” (p. 470).

But would this not be the case if their Vision was in effect the original gospel? The group that produced the first gospel message would not have had to define itself against others until others eventually came forward who contested it or their interpretation of it. Polemics are a feature of practically every early Christian writing. Its absence from the Vision may be an indication that it dates before all of the others.

.

Where?

But where, according to the Vision, did the hanging upon a tree occur? The Son will “descend into the world” (according to 9:13, in some versions of E) and “will be in the world” (per 10:7, in L2), but in no uncontroversial section of the extant text does it explicitly say which part of the world. I am inclined to think the location was understood to be on earth, not in its sublunary heaven. For one thing, 9:13 goes on to say that the Son “will become like you [Isaiah] in form, and they will think he is flesh and a man.” Earth is the home of men of flesh and so it is presumably there that the Son could expect to fool the rulers of the world into thinking he was a man.

I realize one could object that the Son’s persecutors appear to be the spirit rulers of the world and that their home was thought to be in the firmament. But it was also commonly accepted that their rule extended to earth and below it, and that they could exercise their power through human instruments. That is what we see right in the Martyrdom of Isaiah. Beliar kills Isaiah through King Manasseh:

Because of these visions, therefore, Beliar was angry with Isaiah, and he dwelt in the heart of Manasseh, and he cut Isaiah in half with a saw… Beliar did this to Isaiah through Belkira and through Manasseh, for Sammael was very angry with Isaiah from the days of Hezekiah, king of Judah, because of the things he had seen concerning the Beloved, and because of the destruction of Sammael which he had seen through the Lord, while Hezekiah his father was king. And he did as Satan wished. (Asc. Is. 5:1 & 15-16)

True, as already mentioned, parts of the Martyrdom were written after the Vision. But it is nevertheless still a quite early writing, likely dating to the end of the first century. It does not quote or allude to any New Testament writings. But it does clearly allude to the Vision and so may provide us with an indication of how that writing was understood by at least one first century Christian community. If the Martyrdom portrays the rulers of the world attacking Isaiah through a human instrument, this may very well have been the way the prophesied attack on the Son of the Vision was understood too, for he was to become like Isaiah in form (Asc. Is. 9:13) and trick them into thinking he was flesh and a man.

Another consideration that leads me to think the Son’s death in the Vision occurred on earth is the way Irenaeus speaks of Simon of Samaria. One would think, based on what Irenaeus says, that Simon knew the Vision of Isaiah and claimed to be the Son described in it. And in his account the location of the Son’s death is specified as Judaea:

For since the angels ruled the world ill because each one of them coveted the principal power for himself, he [Simon] had come to amend matters, and had descended, transformed and made like the powers and authorities and angels, so that among men he appeared as a man, though he was not a man, and he seemed to suffer in Judaea, though he did not suffer (Against Heresies, 1, 23, my bolding).

In the Panarion of Epiphanius the reason why Simon made himself like the powers is spelled out. Simon is quoted as saying:

In each heaven I changed my form, in order that I might not be perceived by my angelic powers… (2, 2)

It seems to me that in the first passage Irenaeus is relaying an early claim made by Simon, and he is relaying it in the words that Simon or his followers used, not those of Irenaeus. The one “who suffered in Judaea” is not an expression that Irenaeus uses anywhere else to describe Christ. And the claims attributed to Simon in the passage look primitive.

- He doesn’t claim to be the Son who taught and preached in Galilee and Judaea;

- or who worked great signs and wonders among the Jews;

- or who gathered together a band of disciples.

- He doesn’t say he was the Christ who came to lay down his life to atone for the sins of mankind.

The limited claims attributed to him in the passage are reminiscent of the information about the Son in the Vision of Isaiah. Assuming that was Simon’s source, the place where the Son’s suffering was believed to have occurred is specified as Judaea.

I will come back to the question of location in my next post. In this one I want to consider some additional indications that Simon did in fact know the Vision of Isaiah and that it was the source of his gospel. Let’s look in the Pauline letters.

.

The Ignorance of the Rulers of this World

In the second chapter of 1 Corinthians there is this:

2:6 We speak wisdom among the perfect, but wisdom not of this world, nor of the rulers of this world, who are coming to nought.

2:7 But we speak God’s wisdom in a mystery, that hidden wisdom which God decreed before the ages for our glory.

2:8 None of the rulers of this world understood this, for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.

2:9 But, as it is written, ‘What no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor has it entered into the heart of man, what God has prepared for those who love him.’

Scholars recognize the similarity in motif between the Vision’s prophecy that the rulers of this world will crucify the Son “not knowing who he is” (Asc. Is. 9:14) and the statement in 1 Corinthians 2:8 that the rulers of this world, in crucifying the Lord of glory, acted out of ignorance.

But there is more to the relationship than that.

Hidden wisdom and the wisdom of the world

First, Paul brings forward the motif as part of his discussion of the difference between the wisdom of this world and God’s hidden wisdom:

We speak wisdom among the perfect, but wisdom not of this world, nor of the rulers of this age, who are coming to nought. But we speak God’s wisdom in a mystery, that hidden wisdom which God decreed before the ages for our glory. (1 Cor. 2:6-7, my bolding)

Now the Vision, immediately before it begins the account of Isaiah’s ascent, says that the wisdom of this world was taken from him:

And the vision which he saw was not from this world, but from the world which is hidden from the flesh. And after Isaiah had seen the vision he recounted it to Hezekiah, and to Josab his son, and to the other prophets who had come… but the people did not hear, for Micah and Josab his son had sent them out when the wisdom of this world was taken from him as if he were dead.” (Asc. Is. 6:15-17, my bolding)

The Lord of glory

Next Paul, in referring to Christ’s crucifixion by the rulers of this world, employs an expression for him that, in the entire Pauline corpus, he uses only here. He calls him the Lord “of glory.”

None of the rulers of this world understood this, for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory.

In the Vision something similar occurs. The Beloved is mentioned throughout and called ‘Lord,’ but it is especially in his dealings with the rulers of this world that his glory is emphasized. Thus Isaiah’s angelic guide mentions the Beloved several times in chapters seven and eight without even once making reference to his glory. The Lord is glorious, of course, as Isaiah discovers when he lays eyes on him in the seventh heaven (Asc. Is. 9:27). But attention is repeatedly given to that glory once the Vision comes to his engagement with the rulers of this world. When he begins his ascent back to his heavenly home he drops his disguise and lets his glory shine through, for his Father had given this command:

Afterwards you shall not be transformed in each of the heavens, but in great glory you shall ascend and sit at my right hand. And then the princes and the powers and all the angels and all the rulers of heaven and earth and hell will worship you. (Asc. Is. 10:14-15).

And in describing the reaction of the firmament angels, it is the Lord’s glory that is highlighted. The first words out of their mouth are:

“How did our Lord descend upon us, and we did not notice the glory which was upon him, which we (now) see was upon him from the sixth heaven?” (Asc. Is. 11:24)

The Lord continued his ascent with that glory, no longer concealing it by transformations:

But there was one glory, and from it he was not transformed (Asc. Is. 11:29).

As it is written

Last, there is the matter of the scriptural quote Paul brings forward. By using the formula “As it is written” he clearly is appealing to a writing that he considers authoritative:

But, as it is written, ‘What no eye has seen, nor ear heard, nor has it entered into the heart of man, what God has prepared for those who love him.’

This quotation continues to puzzle scholars. It is one whose source they have been unable to positively identify:

The quotation cannot be found either in the Old Testament or in Jewish canonical writings” (1 Corinthians, H. Conzelmann, p. 63).

Some have thought that perhaps Paul was trying to quote 64:4 of the canonical book of Isaiah:

No one has heard or perceived by the ear, no eye has seen a God besides you who acts on behalf of those who wait for him. (Is 64:4)

But the differences between Is. 64:4 and 1 Cor. 2:9 are such that it is hard to believe Paul could have mangled it so badly. The Isaiah verse

- (1) inverts the order at the beginning, mentioning the hearing before the seeing

- and (2) it is missing the words “nor has it entered into the heart of man.”

- Moreover, (3) its object is God himself, not the things he has prepared,

- and (4) it is those who “wait” for God—not those who “love” him—who are the recipients.

In light of these differences some scholars allow that Paul may be quoting an apocryphal scripture.

It is by no means unlikely that the Apostle should quote from an apocryphal apocalypse to support a ‘hidden’ truth. Does not the Epistle of Jude expressly cite the book known as Ethiopic Enoch…? (J. Héring, The First Epistle of Saint Paul to the Corinthians, p. 19)

Paul may indeed be quoting an apocryphal apocalypse, the Vision of Isaiah. The case for this is strengthened by the presence of the verse in the L2 and S versions of the Vision:

This angel said to me, “Isaiah, son of Amoz, it is enough for you, for these are great things, for you have observed what no one born of flesh has observed. What eye has not seen, nor ear heard, nor has it entered into the heart of man, how great things God has prepared for those who love him” (Asc. Is. 11:34).

.

The combination of the above indications constitutes, to my mind, a good case that the author of 1 Cor. 2:6-9 knew the Vision of Isaiah. And the “wisdom” Paul speaks about in the passage was not just a peripheral part of his belief. It was his gospel, “that hidden wisdom which God decreed before the ages for our glory” (1 Cor. 2:7), “the revelation of the mystery which has been kept in silence for long ages… now manifested through the writings of the prophets, made known according to the decree of the eternal God…” (Rom. 16:25-26).

.

The Philippians Hymn

The case that Paul knew the Vision of Isaiah is further strengthened by a passage that many scholars consider to be pre-Pauline: Philippians 2:6-11. They generally hold that it is an early Christian poem or hymn that Paul did not write himself but inserted in his letter to reinforce his exhortation to humility.

It is “a species of pre-Pauline confessional material, thus opening a window on what was believed and taught about the person and place of Christ in the Jewish-Christian and Gentile churches prior to the formative influence which Paul exerted on early Christian thought” (R.P. Martin, Carmen Christi, p. vii).

In the opinion of J. Jeremias, it is “the oldest evidence for the teaching concerning the three states of Christ’s existence which underlies and delimits the whole Christology of later times” (quotation as translated by Martin on p. 23 of Carmen Christi, from Jeremias’ “Zur Gedankenfuhrung in den paulinischen Briefen: Der Christushymnus” in Studia Paulina in honorem J. de Zwaan, ed. J.N. Sevenster and W.C. van Unnik, p. 154).) It reads:

2:5 Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus,

2:6 who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped,

2:7 but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being made in the likeness of men.

2:8 And being found in appearance as a man, he humbled himself [becoming obedient] unto death, even death on a cross.

2:9 Therefore God also highly exalted him, and gave him the name which is above every name,

2:10 that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow, in heaven, on earth, and under the earth;

2:11 and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.

From comparison of the Philippians passage with the Vision it is immediately obvious that they share the motif of descent, crucifixion, and return to heaven.

But the similarity goes beyond that.

Christ as a pre-existent divinity

In both texts Christ is a pre-existent divine being. In Philippians he is in the form of God; in the Vision, even before he accomplishes his commission, he receives the worship of all the righteous and angels of the seventh heaven. But despite his pre-existent divinity, in both texts he is not completely equal with God.

Transformed into the likeness of a man

Next, in both writings attention is given to the transformation of Christ. In the hymn he swaps the “form” (Phil. 2:6) of God for the “form” (Phil. 2:7) of a slave. In the Vision he takes on consecutively the “form” of the inhabitants of the lower six heavens and then a form like that of Isaiah: “become like you in form” (Asc. Is. 9:13). In the hymn the Son “was made in the likeness of men” and “found in appearance as a man” (Phil. 2:7-8). According to the Vision the Son will be “transformed until he resembles your [Isaiah’s] appearance and your likeness” (Asc. Is. 8:10). When he descends into the world in the last days “they will think that he is flesh and a man” (Asc. Is. 9:13). He will be “like a son of man” (Asc. Is. 11:1, in S and L2).

This language of “form,” “likeness,” “resemblance,” and “appearance” in both texts has often given rise to a suspicion of naïve docetism. In the Philippians hymn, “The veil of unreality is cast over his earthly life by phrases that seem to suggest that he was not really human” (F.C. Porter, The Mind of Christ in Paul, p. 210). The Vision’s statement that people “will think he is flesh and a man” seems to imply that the Son didn’t actually become flesh and a man.

The exaltation

Then there is the similarity in their treatment of the subsequent “exaltation” of Christ. In both texts he is exalted even higher than he was before. The hymn says every knee “in heaven, in earth, and under the earth” will bow in worship to him. And every tongue will confess that he is Lord. The Vision says that, after he fulfills his God-given task, “the princes and the powers and all the angels and all the rulers of heaven and earth and hell will worship you” (Asc. Is. 10:16).

At each stage of his ascent he is worshipped and praised by all. The hymn also says he will be given the name which is above every name.

In the Vision Isaiah is told that the Beloved “is to be called Jesus in the world, but you cannot hear his name until you have come up from this body” (Asc. Is. 9:5). According to Knibb this is “apparently a reference to a secret name of Jesus,” but he adds that the names ‘Jesus’ and ‘Christ’ in the Vision may be secondary (“Martyrdom and Ascension of Isaiah: A New Translation and Introduction,” in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, edited by J.H. Charlesworth, note g, p. 170)

Influence?

Thus the similarities are substantial, both in what the two texts say about Christ, and in what they leave out. But despite this, there has been no acknowledgement that one may have influenced the other.

The likeness of the Ascension of Isaiah myth (chs. vi-xi) to the theme of Philippians ii is certainly striking, as Dibelius has shown.

The basic scheme of descent and return is the same in both versions, but in details there is wide disparity. Perhaps the most outstanding difference is the motif of deception which runs through the Ascension of Isaiah drama. There, the kenosis of Christ is a stratagem which aims at concealing the identity of the incarnate one from the rulers of this world. This disguise-motif may be present in I Corinthians ii. 6-8; but it would be hard to detect it in Philippians ii where the Exaltation does not appear as the result of a victory gained through a ruse, but as the consequence of His self-abasement and obedience to the will of God His Father (R.P. Martin, Carmen Christi, p. 220 — [reformatted by Neil])

But if this is “the most outstanding difference,” I don’t see that it amounts to much. For it is reasonable to think that Paul chose the hymn or certain stanzas of it based on their ability to buttress his exhortation to humility: “Let this mind be in you which was also in Christ Jesus” (Phil. 2:5). The lead-in to that verse is:

Humbly regard others as more important than yourselves, each looking out not for his own interests, but everyone for those of others (Phil. 2:3-4).

So is it not likely that Paul deliberately chose what focused on the humility of the Son? What his faithful could imitate was the Lord’s humility, not the deceptive trick he played on the rulers of the world.

As for the obedience mentioned in the hymn, it is also present in the Vision. The Lord clearly carries out his commission in obedience to the command of his Father that he “Go out and descend through all the heavens.” The entire commission in verses 8-15 of chapter 10 is referred to as a command given to the Lord by God:

This command I heard the Great Glory giving to my Lord (Asc. Is. 10:16)

However, I am not confident that obedience was part of the original Philippians hymn. Some scholars have noted that the line that contains it is too long and throws off the balanced structure of the hymn. They propose eliminating the expression “even death on the cross” as a gloss. But I suspect that it is the “becoming obedient” that doesn’t belong. As already mentioned, the lead-in to the hymn exhorts to humility, not obedience. And it is lowly humility—not obedience—that contrasts naturally to the subsequent exaltation as we see, for instance, in the Gospels:

He that shall humble himself shall be exalted (Mt. 23:12; Lk. 14:11)

.

Moreover, Simonians would have had a good reason to later add obedience to the hymn. The etymological meaning of the name ‘Simon’ is “hear, hearken, obey.” The same Hebrew root word underlies the first word of the Shema: “Hear, O Israel…” And Simonians apparently claimed that he was given that name because he had previously obeyed the Father: “They (Simonians) said that he was called Simon, that is to say, the obedient, because he obeyed the Father when he sent him for our salvation.” (Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio, vol. 2, col. 1057, my translation and bolding)

.

Simon/Paul’s Ascension(s)

Another passage that may be relevant for determining if Simon/Paul knew the Vision of Isaiah is 2 Cor. 12:1-4. In it he is apparently responding to an accusation that his prophetic gifts were inferior to those of his opponents. He says “It is not expedient, but I will come to visions and revelations of the Lord” as if he is “turning to a specific point, possibly raised by others” (C.K. Barrett, The Second Epistle to the Corinthians, p. 306).

To defend his prophetic ability he relates at least one but more likely two heavenly ascensions of his own that are similar in some respects to that in the Vision:

12:2 I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know. God knows.

12:3 And I know that this man was caught up into Paradise—whether in the body or out of the body I do not know. God knows.

12:4 And he heard unutterable words that it is not permitted a man to speak.

Thus we have in this passage at least one but, in my opinion, two instances where its author says he was taken up from the earth. The first was to the third heaven and the second to Paradise. He is unsure whether the liftoffs were in the body (like, for example, Elijah) or out of it (as in the case of Isaiah in the Vision: “His [Isaiah’s] eyes indeed were open, but his mouth was silent, and the mind in his body was taken up from him” – Asc. Is. 6:10). He appears to consider the difference irrelevant. Either way, ascensions to the heavens would have been regarded as impressive.

Forbidden to divulge

But what I find particularly interesting is his statement that in Paradise he heard “unutterable words that it is not permitted a man to speak.” On this verse J. Héring comments:

The expression ‘arrhēta rhēmata’ = ‘ineffable words’ may be borrowed from the language of the mystery religions, in which initiates in a supranormal state could hear words uttered by the gods, about which it was necessary either to observe complete silence or pass on the information only to the elect and under pledge of secrecy. It can be seen that ‘arrhētos’ does not necessarily mean ‘inexpressible in human language,’ but at all events forbidden to divulge. The same applies in 12:4 where ‘ouk exon lalēsai’ can only mean: it is forbidden for a man to utter them. It is useless then to seek the content of those revelations in the Apostle’s letters! (The Second Epistle of Saint Paul to the Corinthians, p. 91)

Paul, having said that he heard unutterable words, felt no need to give any more examples of his visions and revelations. It is as if he sees this as his “clincher,” the example that effectively made his prophetic gift indisputable and unsurpassable. It would have put his revelation in the same category as that of Isaiah. And it would have put it, for example, beyond those in the book of Revelation, for this is filled with words supposedly spoken in heaven but whose dissemination is not forbidden. No holding back here, and rightly so if the gospel was the ultimate secret and had finally been revealed.

.

The final generation should have been a time for revelations, i.e., manifestations, not for secrecy.

Unless, that is, Paul had a new secret that was on a par with that of the gospel! The gospel as presented by the Vision of Isaiah entailed the disguised descent of the Lord himself. Could Paul have had a comparable secret?

If I am right that Paul was Simon of Samaria he indeed had such a secret, one whose revelation would lead one “to reckon to my account more than he sees in me, or hears of me” (12:6). The Lord had again secretly descended and was present in Paul. His revelation was comparable to Isaiah’s and, as in the case of the Vision, was to be kept secret until God should decide to reveal it.

| Assuming Paul was Simon of Samaria, I think that about fourteen years after he first came to believe in the Vision his gospel beliefs took on an important addition. At his first ascension he had become an apostle of Christ. At his second he became Christ. The Lord, at his first descent, effected the release of the righteous from hell. At his second he released the Spirit, in the person of Helen, and through her extended salvation to those on earth who have the necessary gnosis. |

.

For this reason he [Simon] came, in order to rescue her [Helen] first and free her from her bonds, then to offer men salvation through his knowledge. .. Therefore those who have set their hope on Simon and Helen pay no further attention to them [the angels who made the world] but, as being free, do what they wish; for men are saved by his grace, and not by just works. (Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 1, 23, 3)

.

Next: In part 8 I will continue discussing the Vision of Isaiah and will address the chapter 11 discrepancy in the readings of E/L1 and L2/S.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Tremendous work, Roger! Definitely worth waiting for!

Regarding the Ascension of Isaiah texts, is it possible that the crucifixion theme is secondary interpolation?

The command given in chapter 10 goes as follows:

8. “Go forth and descend through all the heavens, and thou wilt descend to the firmament and that world: to the angel in Sheol thou wilt descend, but to Haguel thou wilt not go.

9. And thou wilt become like unto the likeness of all who are in the five heavens.

10. And thou wilt be careful to become like the form of the angels of the firmament [and the angels also who are in Sheol].

11. And none of the angels of that world shall know that Thou art with Me of the seven heavens and of their angels.

12. And they shall not know that Thou art with Me, till with a loud voice I have called (to) the heavens, and their angels and their lights, (even) unto the sixth heaven, in order that you mayest judge and destroy the princes and angels and gods of that world, and the world that is dominated by them:

13. For they have denied Me and said: “We alone are and there is none beside us.”

14. And afterwards from the angels of death Thou wilt ascend to Thy place. And Thou wilt not be transformed in each heaven, but in glory wilt Thou ascend and sit on My right hand.

15. And thereupon the princes and powers of that world will worship Thee.”

This suggests that the Christ’s mission was to descend incognito into Hell (?) and then, when God’s voice booms out, to show himself and judge the gods and angels of the lower heavens. The crucifixion is missing. It seems like the Christ might be able to overpower the angels simply by his natural glory and divinity, once he has got in amongst them and into Hell in disguise.

It would be funny if the mission instructions missed out the rather important fact that the Christ would be crucified and killed, whereas this is what the angel predicts at 9:14. It looks possible that 9:14 is an interpolation, as it seems to interrupt the flow of ideas about the hidden descent:

13. Nevertheless they see and know whose will be thrones, and whose the crowns when He has descended and been made in your form, and they will think that He is flesh and is a man.

[14. And the god of that world will stretch forth his hand against the Son, and they will crucify Him on a tree, and will slay Him not knowing who He is.]

15. And thus His descent, as you will see, will be hidden even from the heavens, so that it will not be known who He is.

It looks like the “And thus his descent … will be hidden” follows on from “they will think that He is flesh and is a man”, whereas the line about the crucifixion is a separate idea.

Hence I wonder if the Ascension has been more heavily interpolated than you suggest, and crucially with the idea of the crucifixion.

Earl Doherty discusses the Latin/Slavonic texts (NGNM p. 123) but what is odd about these texts is that there is nothing between “I saw one like a son of man, and he dwelt with men in the world, and they did not recognise him” and the next line “And I saw him, and he was in the firmament…”. Again, no crucifixion. No characeristically Judaean episode. Not even any harrowing of Hell. This is very odd as the heart of the narrative seems to be missing.

It is unfortunate for your theory that the 2 Cor line does not appear in the Ethiopic text, as this suggests it has been added to the original text, perhaps under the influence of the more famous 2 Cor text.

Many thanks for publishing your research!

Text quoted from here: http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/ascension.html

The chapter 10 passage seems to be looking at the Son’s mission as a whole but views it from a single perspective: those angels who have refused to acknowledge any god above them will fail to recognize and worship the Son when he is in their worlds. They will fail to recognize him, that is, until the moment finally comes for him to put aside his disguise. From this perspective the angels who rule the world were guilty from the moment they failed to recognize and worship the Son when he entered their territory. If the chapter doesn’t mention the Son’s human disguise and the failure by people on earth to recognize and worship him, that may be because they are not the ones who said “We alone are and there is none beside us.” (And could God really expect mere humans to see through a divine disguise?)

Note too that chapter 10 doesn’t enter into particular details of what the Son will do or how he will be treated in the worlds of those ignorant angels, whether in the firmament, on earth, or in Sheol. The reason, I think, is because details were provided later, in chapter 11, when the Vision describes the Son’s departure. But alas, the problem is that we are no longer sure what was in chapter 11. In my next post I will go into this.

In regard to the quote in 2 Cor. 9: the verse seems harmless enough but it may be that it was too closely associated with Simon and his ilk from the start. Hegesippus is quoted as saying that the verse contains “empty words” and that “those who say them are liars against the Holy Scriptures and the Lord.” So if he knew 1 Corinthians, for him Paul must have been one of the liars.

And according to Hippolytus, some gnostics used the verse in their initiation rites to describe the insight they obtained: “And when he [i.e. he who is about to be initiated] has sworn this oath, he goes on to the Good One, and beholds ‘whatever things eye hath not seen, and ear hath not heard, and which have not entered into the heart of man'” (Refutation of All Heresies, 1.)

Jerome acknowledged that the verse was in the Ascension of Isaiah but said Paul couldn’t have been quoting that book. The reason, he said, is because Paul would not have quoted a heretical book.

Emma,

I’ve been thinking some more about your comment. If I understand you correctly, you are suggesting that the crucifixion itself may have been an addition to an earlier version of the Vision that didn’t have it. And since the Son’s crucifixion was part of it by the time Paul came to know the Vision (“None of the rulers of this world understood this, for if they had, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory” 1 Cor. 2:8), the insertion would have been made prior to that. Correct?

I have reread the text with your suggestion in mind, and I think there may be something to it. The text does seem to convey that the real fault of the angels in question was their failure (caused by pride) to recognize and proffer due worship to the Son when he passed through their worlds. At the Son’s ascent in glory “all the angels of the firmament, and Satan, saw him and worshipped. And there was much sorrow there [in the firmament] as they said, ‘How did our Lord descend upon us, and we did not notice the glory which was upon him, which we now see was upon him from the sixth heaven” (Asc. Is. 11:24). It does seem strange that there is not a word at that point expressly about the crucifixion. There is no “Boy, we really messed up big time by crucifying him!” Or “Sorry ‘bout that crucifixion” offered to the Son as he soared back up.

You may be right that the original Vision had already been modified (i.e., furnished with a disguised stop and crucifixion on earth) by the time it was embraced by Simon/Paul and the Jerusalem church.

Hi Roger

You make good points. I don’t know know what to think was originally there, since the Latin/Slavonic texts apparently lack the sort of narrative we are led to expect at the climactic moment in chapter 11. The command of God in chapter 10 predicts merely the sounding of the voice of God as the crucial moment. It’s all very vague compared with what we are accustomed to from later sources.

It seems plausible that somebody read crucifixion into Ps 22 (LXX) or identified Christ with an executed rebel, or whatever, and added the crucifixion into the theology and into the text.

Crucifixion is, after all, one of the crucial points that distinguishes some forms of Christianity from others, and from Gnosticisms more generally. So it should not be surprising to see it added into texts. Also, it seems plausible that Paul had to do with some apostles of Christ who were not preaching his crucifixion, given this line:

“You foolish Galatians, who has bewitched you, before whose eyes Jesus Christ was publicly portrayed as crucified?” (Gal 3)

Either the insertion of the crufixion was made prior to when Paul came to know the Vision, or else the insertion was made by Paul himself. Either is consistent with a historicist hypothesis: the killing by crucifixion of an actual teacher might have inspired the addition of crucifixion to the story.

Roger, did Simon already believe–or entertain the idea–that he was Christ when he became acquainted with the Pillars? Or did that idea arise after his initial contact with the Jerusalem Church?

As far as I know, the early Christian literature nowhere says when it was that Simon first claimed to be the Son who had—in appearance—suffered in Judaea. So I can only offer you my own speculation. I suspect Simon/Paul became convinced he was Christ sometime between his first visit with Cephas in Jerusalem his second (and final) visit there. And it was probably closer to the second visit than the first. In other words, I think he was supposedly caught up to Paradise and heard the unutterable words only a short time before he wrote the Corinthian and Galatian letters. 1 Thessalonians may be the only one of his extant letters that dates to a time when he viewed himself as just an apostle of Christ.

My reasons for the above scenario should become apparent later in the series.

Hi Roger,

Thanks again for all the thought-fodder. One implication of your thesis, I think, is that it rules out a Stoic interpretation of Paul’s theology. I am thinking of Troels Engberg-Pedersen and others who see in Paul a strong philosophical influence, with E-P in particular arguing for a Paul conceiving of his Christ in much the same way Stoics conceptualized Reason/Logos — as a being or entity living in the Stoic. Am I correct in seeing not much room for that thesis with your own?

I don’t think Paul conceived the Son of God as just “conceptualized” Reason/Logos. The Vision of Isaiah presents the Son as a distinct divine personage higher than the angels but still subordinate to God. The Beloved and the angel of the Spirit receive worship but they, in turn, worship the Father. If Paul is indeed Simon of Samaria, he may at some point have meshed this very high view of the Son and Spirit with his own earlier Apophasis Megale idea of divine powers that emanated from God. He and Helen were God’s two highest powers.

This is a very, beautiful Summa of the best Christ-Myth Theory!

by acknowledging my debt to Earl Doherty.

I like this premise because I have thinked sometimes that your extreme scenario has a historicist tendence, but this is not the case, evidently.

I saw a old film on TV the other day, The Minion, where in that case it is a servant of Sathan to descend on heart in incognito. But the ”docetic” view of that film can be labeled ”historicist” because the daemon spirit transfers itself into the next available host body when his previous one is killed off (and there is not a switch of places between the holographic phantom and the real man, as in your view of original Gospel).

Happy New Year to Vridar!

Roger, can you tell us something about the “Sanctorum Conciliorum et Decretorum Collectio Nova”. What is this, exactly?

Further, can you elaborate a little on what you understand by Paul having a new revelation that had to be kept secret until the time God decided it be revealed. I’m thinking of those passages where Paul speaks of Christ in him. Are you saying that this is the secret of the second revelation? Was Paul saying Christ was uniquely in him and in no-one else?

Thanks,

Neil

Neil,

The “Sanctorum Conciliorum et Decretorum Collectio Nova” is a collection of texts promulgated by church councils or related to them. The one I referenced in my post contained a catalogue of various heresies put together by Maruta of Maipherkat, a fourth century Syriac bishop. The catalogue has a few lines about Simonianism, including the bit about how Simonians explained the significance of Simon’s name.

To your second question: Yes, I think Simon/Paul believed that the Beloved Son described in the Vision of Isaiah had descended anew and taken up habitation in him. But the Son’s mission this time was different. He came to release his divine yokemate Helen (the Holy Spirit) and, through her, to start gathering the rest of his divine pieces scattered on earth. Through participation in the released Spirit, Christians are compacted as the body of Christ. So, in that sense, all Christians are “in Christ.” But God’s Son is the head of that body. And it was the head of the body that took up habitation in Simon/Paul.

Regarding the passages where Paul speaks of Christ being “in him:” I think he chose his words carefully so that only the privileged ones with whom he had shared his secret would “get” the full meaning of what he wrote. Héring is probably right that “It is useless then to seek the content of those revelations in the Apostle’s letters!” The content was something “about which it was necessary either to observe complete silence or pass on the information only to the elect and under pledge of secrecy.” (The Second Epistle of Saint Paul to the Corinthians, p. 91). It is the language of mystery religion.

Roger,

About Sanctorum Conciliorum etc: What is the original Latin passage and where can we find it?

To what council is that catalog of heresies related?

It appears that your reference and your link might be mistaken.

Your reference is to column 1057 in volume 2, but your link is to the title page of volume 4; column 1057 in that linked copy of volume 4 does not appear to contain the passage.

I found an online copy of volume 2 on the hathitrust site; again, column 1057 does not appear to contain the passage.

Clyde,

You’re right. The “Sanctorum Conciliorum et Decretorum Collectio Nova” is the supplement that Mansi made to Coleti’s collection of conciliar documents. It is the “Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio” that is Mansi’s own collection. I will correct the reference.

The Latin of the passage I translated is:

“Hunc sequaces Simonem … apellatum fuisse Simonem dicebant, id est, obedientem, quia obedivit Patri mittenti illum ad nostram salute.

The catalogue of heresies was not a conciliar document. It was in a collection of writings by Maruta, most of which were about the 325 CE Council of Nicaea. As mentioned in my original response, Maruta was Syriac. The Latin translation of his writings that is in Mansi’s collection was made by a 17th century Maronite named Abraham Echellensis.

Too tired! The “salute” should have an “m” on the end of it.

Roger,

Thanks for your reply. I am finding your Simonian series most interesting.

‘The “Sanctorum Conciliorum et Decretorum Collectio Nova” is the supplement that Mansi made to Coleti’s collection of conciliar documents. It is the “Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio” that is Mansi’s own collection.’

So to which did you intend to refer? The latter?

Yes. You will find the quote there in column 1057 of tome 2.

Excellent work, Roger!

As a related aside, the Epistle to the Hebrews (Heb. 11:37) may contain an allusion to Isaiah’s martyrdom at the hand of Manasseh and the instigation of Beliar:

They were put to death by stoning; they were sawed in two; they were killed by the sword. They went about in sheepskins and goatskins, destitute, persecuted and mistreated– (Heb 11:37 NIV, emphasis mine)

Fascinating series of posts.

I have been reading more recently about the whole Arian controversy, and it seems to me that Arians would have loved The Ascension etc.

Is there any idea when this text was suppressed? If Jerome was aware of it, perhaps after the Third Council Of Carthage?

Again, looking forward to your next post

I don’t know that it was ever actually singled out for suppression, at least not any more than other books that were deemed heretical by the church that achieved dominance in the 4th century. Modified versions of it were used by the Abyssinian church, and later by the Bogomils and Cathars. But I think its “demise” really came about more as a result of its becoming irrelevant once a gospel was written that added a public ministry to the Vision’s crucifixion narrative. UrMark, in my opinion, was that gospel; a Simonian composition that put an allegory about Simon/Paul in front of the Vision’s crucifixion story. The gospels that followed this new style gospel—even those that attempted to correct its teaching—adopted the new and improved format. And with the proliferation of those gospels and the development of Christian doctrine, the Vision was either discarded as inadequate or avoided as heretical.

Thanks

Roger,

What a great article! You have convinced me that both Simon and Paul depended on the Ascension of Isaiah, which is another giant leap forward toward accepting that Paul was Simon.

On Simon’s belief that the spirit of Christ transferred from Jesus to him, do you think this was portrayed allegorically in the Synoptics by transferring the cross from Jesus to Simon of Cyrene? If so, the fact that all the Synoptics have it suggests that the proto-orthodox community never recognized this meaning. And if the gospel of John is Marcionite (as Dr. Price suggests), the absence of this story of Simon is surprising.

I’m thinking that up until now I may have overlooked something important about Paul’s claim that he ascended to Paradise and there heard “unutterable words, things that it is forbidden to a man to speak” (2 Cor. 2:4). I have always assumed that the forbidden words were ones that he had not even divulged to his churches, that they were words for his ears only. That assumption could be wrong. Maybe the reason Paul doesn’t say more here is because it was unnecessary. He knew his first readers would instantly recognize what words he was referring to. He knew they would recognize that he was referring to the gospel that had been revealed to him. How so?

As I have explained in this series, I think that Paul knew the Vision of Isaiah, i.e., chapters 6 – 11 of the Ascension of Isaiah, and that the Vision was the gospel he preached. Now at the end of the Vision Isaiah makes King Hezekiah swear that he will not divulge its contents: “And Isaiah made him swear that he would not tell this to the people of Israel, and that he would not allow any man to copy these words.” (Ascension of Isaiah 11:39). This statement, as M.A. Knibb noted in his translation of the Ascension, was just an apocalyptic fiction which was intended to explain how the Vision remained unknown for the hundreds of years that passed between the time of Isaiah and that of the Christians. It supposedly remained unknown because King Hezekiah, at Isaiah’s behest, forbade that it be divulged.

So if the Vision was indeed Paul’s gospel, it could be what he is referring to in the 2 Corinthians passage. The gospel was Paul’s pride and joy. To me it seems quite plausible that he would bring the revelation of it into that part of the letter where he is putting his “visions and revelations granted by the Lord” (2 Cor. 12:1) up against those of his opponents. He would be pitting the revelation of his gospel against anything they have to offer, in effect saying: “Let me remind you that not only have I ascended to the third heaven, I have traveled clear to Paradise and there heard the words of the gospel message I preached to you, words that – as you know – were forbidden ever since the days of Isaiah.”

In this scenario Paul would not only have known the Vision of Isaiah, he would be the one who revealed it to the first Christians. This would be the gospel that he put before the leaders of the Jerusalem church. They no doubt had plenty of their own “visions and revelations” about the Son of God (for example, the kinds of things we see in the book of Revelation), but I am thinking that Paul’s was the one that revealed the Son’s crucifixion to them. If the Galatians account of Paul’s visit to Jerusalem can be believed, his revelation received the approval of the pillars. I expect it was because they interpreted the crucifixion of the Son as some kind of atonement for sin. I doubt that Paul understood it that way, and the Vision of Isaiah gives no indication it should be interpreted that way. At some point the differences in interpretation became apparent and the honeymoon was over.

[Two additional observations:

1. Like the “Vision of Isaiah”, Simon of Samaria’s “Great Announcement” also involves the revelation of a hidden writing: “This is the WRITING of the REVELATION of Voice and Name from the Thought, the Great Power, the Boundless. Wherefore shall it be SEALED, HIDDEN, CONCEALED, laid in the Dwelling of which the Universal Root is the foundation” (Hippolytus, Refutation of All Heresies, 6,9, my emphases). So if Paul was indeed Simon of Samaria and if indeed he did spring the Vision of Isaiah upon the early Christians, it would appear that when he converted to Christianity he brought his modus operandi with him.

2. Isaiah’s ascension was clearly out-of-body. In the 2 Corinthians passage Paul twice says that he doesn’t know if his own ascent was in the body or out of it. He appears to want to avoid the issue as being irrelevant to the point he is making. But clearly he doesn’t rule out the possibility that he went up to Paradise without his body. Regarding this Victor Paul Furnish writes: “One would suppose, on the basis of 1 Cor 15:35-50, that a bodiless journey would have been inconceivable to Paul – just as it was, theoretically, to anyone whose anthropology was essentially Jewish …” (Furnish’s Anchor Bible commentary on II Corinthians, p. 545). I agree. My guess is that the resurrection treatise in 1 Corinthians wasn’t written by Paul.]

Is my memory correct in that I think you have said you interpret the Asc. Isa. as implying the Beloved descended to earth itself for the time necessary for him to be crucified?

Your memory is correct. In the 8th post in the series I laid out a speculative scenario in which the Beloved descended to earth itself for only the few hours needed to get crucified. My enthusiasm for that scenario, however, has waned. That scenario could explain the hole in Paul’s letters regarding a public ministry and passion narrative for Jesus, but it seems to me the hole would be just as well accounted for if Paul knew one of the extant versions of the Vision of Isaiah.

At present I am inclined to bet on the Ethiopic version, even with its longer chapter 11 that includes the docetic birth scene. Paul’s knowledge of that strange narrative could explain why he does not use the more natural word for “born” in Gal. 4:4. The Vision’s docetic Son could be said to “come of a woman” without really being “born” of her. And the tenuous way Galatians connects Jesus with the Law (“come of a woman, come under the Law”) again seems to make sense if the Vision was Paul’s gospel. The Vision says nothing about the Law or the Son’s stance regarding it. So if Paul wanted to use it to bring both Jesus and the Law onto the same stage, the “coming” of Jesus by way of a Jewish mother was pretty much the only way to go.

Hi Roger,

do you think that the docetic birth of Jesus was imagined in heaven (just as in Revelation) followed by his hidden existence (to escape to Satan) until the moment of the his Death on the Earth (even then still hidden and not recognized, always to escape Satan) to reveal himself only after the his Death ?

Or do you think that the docetic birth happened on the earth, too ?

My comment referenced the Ethiopic version of the birth Asc. Isa.I 11:2-22). I don’t know of anyone who thinks that was believed to have occurred in heaven. Do you?

No, I don’t. It is an earthly docetic birth.