.

| Continuing the series on Thomas Brodie’s Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery, archived here.

This post concludes chapter 17 where Brodie is analysing John Meier’s work, A Marginal Jew, as representative of the best that has been produced by notable scholars on the historical Jesus.

|

Brodie’s discussion of the four Greco-Roman source references to Jesus is brief.

Brodie’s discussion of the four Greco-Roman source references to Jesus is brief.

Tacitus (writing c. 115 CE) writes:

Nero . . . punished with . . . cruelty, a class of men, loathed for their vices, whom the common people [the vulgus] styled Christians. Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilate (Loeb translation). (p. 167, from Annals, 15.44)

Brodie essentially repeats John Meier’s own discussion found on page 91 of volume 1 of A Marginal Jew, commenting that there is nothing here that would not have been commonplace knowledge at the beginning of the second century. (Brodie relies upon the reader’s knowledge of Meier’s work to recognize this as Meier’s own position.)

Brodie adds that Tacitus regularly used older writings and always adapted their contents to his own style. As pointed out by Charlesworth and Townsend in the article on Tacitus in the 1970 Oxford Classical Dictionary Tacitus “rarely quotes verbatim”. By the time Tacitus wrote, Brodie remarks, some Gospels were decades old and “basic contact with Christians would have yielded such information.” His information could even have been inferred from the work of Josephus.

As for Suetonius (shortly before 120), Pliny the Younger (c. 112) and Lucian of Samosata (c. 115-200), Brodie quotes Meier approvingly:

[They] are often quoted in this regard, but in effect they are simply reporting something about what early Christians say or do; they cannot be said to supply us with independent witness to Jesus himself (Marginal Jew: 1, 91). (p. 167)

| I am even more sceptical about the contribution of Tacitus. Recently I posted The Late Invention of Polycarp’s Martyrdom (poorly and ambiguously title, I admit) drawing upon the work of Candida Moss in The Myth of Persecution.

Moss shows us that it was only from the fourth century that the stories of martyrdoms and persecutions that so often dwelt luridly on the gory details of bodily torments became popular. The passage in Tacitus with its blood-curdling details of tortures fits the mold of these later stories. (Moss herself, however, does not make this connection with Tacitus.) This brings us to the late fourth-century monk Sulpicius Severus (discussed by Earl Doherty in Jesus Neither God Nor Man, p. 618-621) who supplies us with the first possible indication of any awareness of the passage on Christian persecutions in the work of Tacitus. This topic requires a post of its own. Suffice it to say here that I believe there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that this detailed passage on the cruelties inflicted on the Christians was “borrowed” from the account written by Sulpicius Severus.

|

Conclusion regarding the five non-Christian authors

Brodie thus concludes that none of the five non-Christian authors provides independent witness to the historical existence of Jesus.

None met Jesus; none claimed to have met anyone who had known him; none claimed to have met someone who knew a friend who knew someone who had known him. None supplies us with any information that is not already found in the Gospels or Acts. (Josephus even lived within walking distance of Christians in Rome.)

General conclusion regarding A Marginal Jew

Brodie’s conclusion about Meier’s famous work is applicable to most notable works attempting to explore the historical Jesus. It/they provide us with invaluable background information for New Testament times and much in the way of treasured insights into the New Testament itself. In such works, we learn much about the history, sociology, economy, and archaeology of the Holy Land. But the strength of Meier’s and comparable works is also their potential problem:

[I]t can leave the impression that knowledge of background provides knowledge of Jesus. (p. 168, citing Neill and Wright, 1988: 207-208)

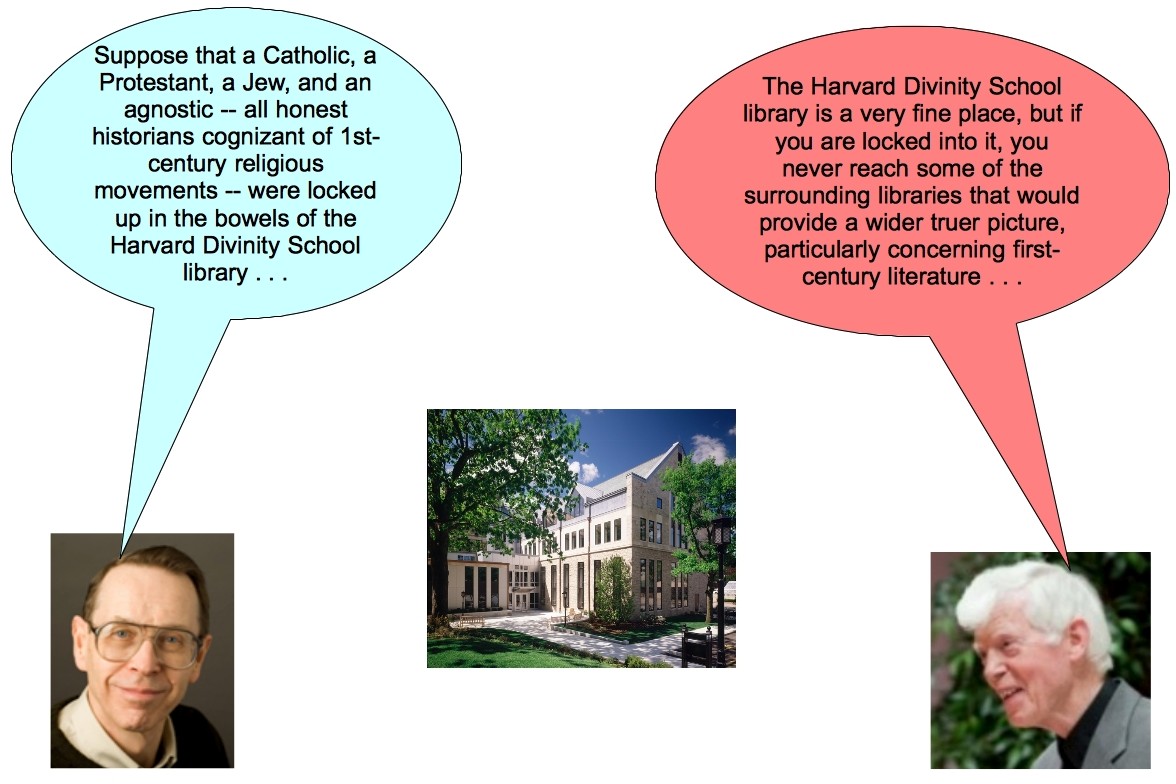

Brodie actually identifies the “root problem” of Meier’s A Marginal Jew in its very first page. There Meier writes:

To explain to my academic colleagues what I propose to do in this book, I often use the fantasy of the “unpapal conclave.” Suppose that a Catholic, a Protestant, a Jew, and an agnostic [What happened to the atheist?] — all honest historians cognizant of 1st-century religious movements — were locked up in the bowels of the Harvard Divinity School library, put on a spartan diet, and not allowed to emerge until they had hammered out a consensus document on who Jesus of Nazareth was and what he intended in his own time and place.

Brodie responds:

The Harvard Divinity School library is a very fine place, but if you are locked into it, you never reach some of the surrounding libraries that would provide a wider truer picture, particularly concerning first-century literature, of which the New Testament is a part, as is Josephus. (p. 168)

General Conclusion: the Nature of the Gospels, Acts and Epistles

In simplest terms, Brodie’s point is that “the main New Testament documents look historical but are not.”

Epistles

These appear to be spontaneous letters written by one main figure as responses to specific historical situations. Detailed literary analysis, however, shows them to be constructed with “a degree of complexity and precision” with respect to both their sources and final shape that sets them apart as “formal epistles”, not spontaneous letters.

Gospels and Acts

These imitate history. They do reflect their historical background. But literary analysis shows us what sources they used and how they used them, and shows us the nature of their art, so that we can see they are not history.

From here Thomas Brodie ventures into the theme of the final section of his book. He offers his opinion of the reason the authors made their work so “history-like”.

The history-like way of presenting the New Testament documents is not simply to reach people. It is an expression of the conviction that God is in human life, in the fiercely specific reality of history, even in events as horrendous as the crucifixion. . . . (p. 169)

That the New Testament literature is “history-like” but not historical is, Brodie concludes, “the simplest explanation that accounts for all the data”, and in saying this he returns to the quotation of John Meier that I have placed at the beginning of this section.

I will leave Brodie’s work for a short while now and focus on a few other things. I do need to return to finish part five of Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus in order to do Brodie justice to where he is coming from as a “mythicist”. The next section, Act 5, will be the hardest part for me to address adequately since the mind-set (especially towards scientific naturalism) and faith Brodie expresses are so contrary to my own.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“By the time Tacitus wrote [c115], Brodie remarks, some Gospels were decades old ….”

Hmmm. “Decades”?

Dunno about that.

Maybe one of them.

Just.

“Christus’ or ‘Chrestus”?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tacitus_on_Christians

“In 1902 Georg Andresen commented on the appearance of the first ‘i’ and subsequent gap in the earliest extant, 11th century, copy of the Annals in Florence, suggesting that the text had been altered, and an ‘e’ had originally been in the text, rather than this ‘i’.[15] “With ultra-violet examination of the MS the alteration was conclusively shown. It is impossible today to say who altered the letter e into an I.”

I bring up both the pedantic points [this and the one above] to suggest that our discussion of the history of Christianity has been so smothered in orthodox received belief that we accept many doubtful ‘facts’ at face value and move on to other points having accepted as superstructure information that is not as solid as tradition likes to present.

The chronology of the gospels and whether Tacitus used a different name than Christian being 2 relevant examples in this context.

Maybe Tacitus did use ‘Christus’ and not ‘Chrestus’. maybe he didn’t, maybe the gospels were written mid to late first century well before Tacitus, maybe not.

In both these cases, and many others, I would consider a detailed excursus necessary to either establish the validity of the points raised before continuing or, somewhat less satisfying for orthodoxy, that these cases are not able to be confirmed to a degree necessary to continue as if they are, pardon me, the gospel truth.

OK we may get bogged down in a near infinite spiral of fact checking but at least we can proceed without having made presumptions without examination.

This is not meant to be a criticism of you Neil, rather just to show how easy it is to accept bricks as sound and use them to build a structure, as Brosie appears to have done, when in reality the bricks are fragile.

Carrier’s essay on “Ignation Vexation” illustrates my point.

http://richardcarrier.blogspot.com.au/2008/09/ignatian-vexation.html

No criticism felt. I agree wholeheartedly with what you are saying. Too much biblical scholarship really does come across as the product of a bizarre scene out of Gulliver’s Travels. So much weight is placed on will o’ the wisps whenever it suits simply to be able to declare the discoveries of answers to questions that satisfy our own ideological interests and that the extant data can never in a million years really substantiate. Of course, when another scholar finds the will o’ the wisp nature of the data supports his or her agenda, then that will be the new profound presentation. And back and forth they go, so often about a whole lot of utter irrelevancies and fantasies they seem to confuse with profundities. No wonder they hate pesky outsiders who would have them getting bogged down in a near infinite spiral of fact checking! So many really are such easy targets for outsiders who can see exactly what they are doing and the tenuous nature of the data they are building on.

You just have to look at the astonishing pseudo-scholarship of a work like ‘Jesus and the Eyewitnesses’ by Richard Bauckham to know that a disciple which tolerates such standards of ad hocery is not a discipline that is producing useful results.

Instead such witchcraft scholarship is actually lapped up! See http://www.christilling.de/blog/2007/01/bauckhams-jesus-and-eyewitnesses-part_20.html for a gushing acceptance of Bauckham’s work , which actually seems to draw heavily upon Drosnin’s Bible Codes in its ability to find hidden messages in the text.

Does anyone know how to contact Brodie? Considering the cool reception his latest book has received from the Jesus Academy, it would be good to write him some encouraging words. Most of all, he needs to keep writing.

Your best bet is to try to message him through his publisher. Use the business email address at Sheffield Phoenix.

I might add that I’m not sure if Thomas Brodie would be very chuffed with his work being addressed positively on an atheistic, naturalistic site like Vridar.

I’m just reading your posts on Thomas Brodie’s latest book and find myself intrigued by the man’s thinking to learn more about how he reasoned.

I can’t seem to turn up any other writings of his; can anyone give me a clue as to where to look for on-line articles written by Thomas Brodie?

I can find his books via Amazon, but was hoping to see articles of his, if they exist.

Ah.

I see I can read his books on-line at google books.

Well, chunks of them, anyway.

If anyone knows of on-line articles of Thomas Brodie’s, I’d be glad to know of them.

You might try searching on Google Scholar. Check a uni library electronic database if you think you can get access to their full text. In the bibliography in his latest book he cites articles he published between 1978 and 2011 in:

JSNT – Jnl for the Study of the NT

BTB – Biblical Theology Bulletin

PIBA – Proceedings of the Irish Biblical Association

ExpTim – Expository Times

JSOT – Jnl for the Study of the OT

The Bible Today

CBQ – Catholic Biblical Quarterly

Bib – Biblica

RB – Revue Biblique

IBS – Irish Biblical Studies

Journal of Higher Criticism

BETL – Bibliotheca ephemeridum theologicarum lovaniensium

He also has chapters in various books edited by D. MacDonald, E. Richard, D.J. Lull, C.H. Talbert

Thanks for the heads-up.

Off to investigate.