It’s been a long time since I read a novel and in the last two days I remembered why it has been so long. Good novels devour me. I’ve read hundreds (no doubt many, many hundreds if you add novels for children and adolescents that I devoured as a teacher-librarian) and when I’m hooked on one everything else — work, household, sleep — takes a backseat till I finish it. In recent years I’ve chosen to focus on nonfiction — sciences, history, current affairs and media, psychology, anthropology and biblical studies mostly. Reading novels at the same time will put a halt to all that and more, especially since I am a way too terribly slow reader for my liking.

It’s been a long time since I read a novel and in the last two days I remembered why it has been so long. Good novels devour me. I’ve read hundreds (no doubt many, many hundreds if you add novels for children and adolescents that I devoured as a teacher-librarian) and when I’m hooked on one everything else — work, household, sleep — takes a backseat till I finish it. In recent years I’ve chosen to focus on nonfiction — sciences, history, current affairs and media, psychology, anthropology and biblical studies mostly. Reading novels at the same time will put a halt to all that and more, especially since I am a way too terribly slow reader for my liking.

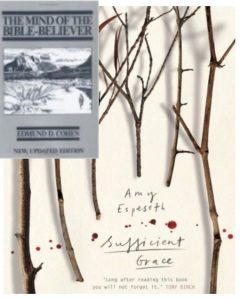

Over the last two days I have read a novel by an American who is now living in Australia, Amy Espeseth, Sufficient Grace. I blogged on this novel a month ago after hearing a radio interview with the author — The Beauty and Pain of Fundamentalist Religion. Since then (partly in response to Amy herself who tweeted me to say she’d be interested to know what I myself thought of the novel) I found a second hand copy on eBay (if I paid full price for every book I own I’d be enslaved to multiple mortgages) and read it as soon as it arrived. I could scarcely resist making it a reading project of mine since I also, after leaving a conservative or fundamentalist type of religion, had often toyed with the idea of writing a novel about my experience, too. Several plot-lines ran through my head.

In some ways the first part of the novel was not quite what I had expected from what I heard on the radio interview. The interviewer, as I recalled, spoke of the church folk living a life of something akin to happy innocence, at least on the surface. The author was said to clearly feel a real sympathy for these people. Yes, I could feel the sympathy. How can we not feel sympathy for many loved ones we have left behind? But Amy Espeseth’s novel is, at least according to the way I read it, many metaphors within metaphors. The families thrive on hunting, and the animals and nature are, to my mind at least, clearly foils setting the stage for the theme that is to soon erupt in lava flows. I felt the hard and cruel signs that something was not quite right beneath the surface of the lives of these God-fearing and self-contained people. Perhaps that’s where my own experiences took over and prepared me well for the horrific tragedy to come.

Amy’s experience was quite different from mine. She writes from the perspective of a child born into the separatist religious group. The experiences she relates, nonetheless, are very much the same kinds of experiences I myself came to know. The details are different — I cannot share critical experiences that belong to women — but I understood exactly the life of cognitive dissonance, of rejection of the world, of mangling of all normal concepts of integrity and word-meanings and holy terror that she narrates. Especially cognitive dissonance. The constant refrains of prayers and hymns and messages from Bible readings and sermons serve to keep one’s mental state in an escapist world of make-believe. The realities of pain, suffering, senseless loss are thought to be “overcome” by the spirit and love of God and faith in Jesus and his blood. In reality they are never overcome. They are overwhelmed from view by prayers and holy thoughts. They are never overcome. The faith really serves to confine the faithful to an immaturity, a childhood that can never face and accept reality. Reality is of the devil and must be overcome. That is, denied. Supplanted by holy thoughts.

This is a huge topic. Worthy of many novels and nonfiction works. I could, and maybe will, use this novel as a foil to address several other aspects of the coffined religious life. So in this post I’ll zero in on just one point, one that I recall from Edmund Cohen’s The Mind of the Bible Believer. I could elaborate upon this with reference to Amy’s novel but then I’d be giving away the climactic second half of what it’s about.

Here is the point expressed more formally than anything Any Espeseth writes. I have broken the original up into several paragraphs and added bolding.

In spite of all the Christian declamation I had heard about the resolution of guilt being a forte of Christianity, from my extensive exposure I knew of no instance where Christianity had helped anyone handle a truly weighty burden of guilt. Neither in first-hand experience, including an ongoing criminal-defense law practice, nor from the media had I encountered it!

I know of plenty of cases where someone had a shame problem — Charles Colson is a conspicuous and typical example — and wanted to demonstrate to himself and to society the turning of a corner in life. Persons who are genuinely helped over a substance-abuse problem, with a shame problem embedded in it, are a special case, whose main features have fairly little to do with guilt or sufficient self-esteem.

Of people whose act or neglect caused terrible human harm, people for whom experiencing compassion for their victim or victims would cause anguish, one hears extraordinary little in Evangelical circles.

Evangelicals are guilt dilettantes, not people who really know about the vicissitudes of substantive, realistic causes for remorse. Being “delivered” from a vague, background sense of guilt with insignificant causes, or no cause at all, is a pastime of theirs.

If there are any who do have heinous things on their consciences, they do not “witness” about them. Not all such people could have current, practical reasons for keeping quiet about their former guilt problems, disobedient to the applicable devotional program instruction. If conservative Christian groups typically do have persons whose pasts include heavy guilt, their consistent failure to “witness” about it points at least to the failure of religion to help them resolve it. (pp. 257-58)

Mindgame: Take a real villain who has blood or other excruciating human suffering on his or her hands and go through the script. How does it work out?

I think of a good friend of mine years back who only found escape from his guilt through suicide. The only alternative he knew he had was Jesus’ blood.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I remember listening to a member of our assembly giving his testimony at the gospel service one Sunday evening over fifty years ago. The brother had been in the merchant navy many years earlier and had travelled to the Far East where doubtless he experienced what would pass these days as fairly typical behaviour for a yong man far from home with a little money in his pocket.

However, according to his testimony, he was the very worst of sinners. Was he a murderer, a fornicator, a gambler, or just an occasional partaker of the everyday naval rum, bum and concertina I have no idea. But he claimed that his misdemeanours were so bad that he couldn’t even begin to hint at what they might have been. This was a bit of a let down to this innocent but inquisitive teenager who would have liked to have had some meat attached to the bare bones of the penitent’s confession. But the man’s distress, if undemonstrative, seemed real enough and was of such uniqueness to the usual humdrum testimony that we would have to put up with when a visiting speaker couldn’t be found that it has stuck in my mind ever since.

So at the age of about fourteen, i decided that far from getting saved that Sunday evening long ago I would wait until I too had enjoyed some of the dreadful pleasures our nervous brother was hinting at. There didn’t seem much point in getting saved from sins I hadn’t yet committed or would be unlikely to commit if I had got saved too early.

Unfortunately, I never did join the merchant navy or any such similar organisation which would have led me into venal ways (other than three years at university for which becoming a Roman Catholic rather than a Christian would have been sufficient to assuage any typical student behaviour) and so I remain unsaved to this day. As for guilt, any remorse is mainly for sins of omission rather than commission. And, if I have any shame, I’m certainly not going to stand up in public and tell any fourteen year old who might be in the audience about it. He might tell you lot in years to come.

By no means all were “guilty” I am sure, but some penitents do also come across as wearing their past sins like an honour badge of grace before God and the brethren. There is in some a keenness to boast about what they have been forgiven. It struck me as a very curious game that was being rationalized by the doctrine of forgiveness.

“This is a huge topic.” You can say that again.

I recall Jimmy Carter talking about the “endless well of forgiveness” to which some sociopathic born-again men return again and again. And what spurs them to return and say, “Ah bin such a bad boy,” is not guilt but the fact that they got caught . . . again.

The public confession in which the “bad boy” admits to whatever sin almost always ignores the victims. The effectiveness of truth and reconciliation commissions lies in their focus on what really happened, who did it, who was victimized, and how to prevent it from ever recurring. However, the superficial forgiveness in Evangelical churches focuses on the sinner — and not even his sins, but how they’ve been magically washed away. That forgiveness, by the way, is presented as a fait accompli, so if you were one of his victims, what can you say?