Hoffmann is continuing his “engagement” with mythicism. My initial thoughts on his latest post follow.

Whatever else Paul was, he was the greatest revolutionary in history when it comes to the God-concept. His ideas were completely unhistorical and at odds with Jewish teaching: he finessed his disagreements into a cult that turned the vindictive God of his own tradition into a being capable of forgiveness. Needless to say, the way he arrives at this is angstful and tortured, but he gets there in the end–not through tradition and law, but through a strategem: ”Christ the Lord.” His turnabout from Judaism was so complete that his only intelligent interpreter, Marcion, believed he must have been speaking of a completely different God. . . .

Hoffmann has argued that the most fundamental reason we should believe Jesus was a historical figure (at least the figure Hoffmann sees after he strips away most of what the Gospels say about him) is that he was so typical of his time. Paul, on the other hand, must be seen as so atypical of his time.

But leaving that discussion for another time, what I find odd in Hoffmann’s claims here is his view of Judaism in the time of Paul. He equates Judaism of Paul’s time with a vindictive God tradition incapable of forgiveness. I am astonished that Hoffmann would write such unsupportable caricature as if it were fact. His view is surely out of touch with most scholarship that has addressed this question.

Sad, it seems to me, that so much of the mythicist argument is based on what Paul does or doesn’t say about Jesus, considering there is a world of thought there that, cast to one side, makes it virtually impossible to know what Paul was talking about. Mythicism, among it many other dubious achievements, has achieved a new level of illiteracy in relation to Paul’s ideological and religious world. . . .

And this comes from someone who has recently argued that we can know that Paul was addressing the illegitimacy of Jesus when he wrote that Jesus was “born of a woman, born under the law” in Galatians 4:4! I have often addressed current scholarship on the writings of Paul. I know of mythicist arguments that draw reasoned conclusions on the basis of the scholarship specializing in Paul. I would like to see Hoffmann himself engage with Pauline scholarship itself, and arguments based upon it, rather than appear to completely bypass it and fault mythicists who take the trouble to take it seriously.

His “biographers” tell the story of a man who preached a kind of mock civil disobedience, but was as critical of Jewish legalism and ritualism as it was of Roman boots in Jerusalem. They tell us he gathered an unpromising following of women and yokels (Celsus’s words, not mine), failed to achieve whatever it is he wanted to achieve, and died among thieves as an enemy of the nation.

There is absolutely nothing improbable about this story. . . .

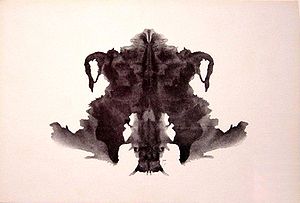

Unfortunately for Hoffmann’s case, this is the very story that the “biographers” do not tell about Jesus. This story is entirely what Hoffmann sees when he looks at the Gospels as if they are a Rorschach test. Now Hoffmann has claimed to have found around 35 details about Jesus that are “probably true” from his Rorschach reading of the Gospels. (If he understood the principle of Occam’s parsimony he would also understand that such a reading makes his Jesus less likely rather than more likely.) The way Hoffmann needs to be able to establish the validity of his reconstructed Jesus from texts that portray a completely different sort of Jesus is to do so without reference to his 3 Cs.

That is, he needs to show that his particular Jesus is objectively or at least validly drawn from the evidence of the Gospels and not just another case of question-begging. If his interpretation is based on his 3 Cs then his method has guaranteed he gets the Jesus he wants to find, a 3C Jesus. He needs to establish for us that his Jesus is constructed independently, and that then lo and behold, the end product is indeed “historical”. I don’t believe he can do that (he would be the first in the history of HJ scholarship to manage such an achievement for his HJ), but I’m willing to be surprised.

One has to be committed to the view that Jesus was the son of God to think he was unusual. One has to be committed to the view that he cannot have been what the gospels say he is (and they say different things, not one thing) to deny his historical existence. . . .

This is garbled. To be a mythicist one has to be committed to the view that Jesus was not really the person the Gospels portray? Does anyone (apart from the devout faithful) really believe that the way the Gospels portray Jesus reflects a historical person? Hoffmann himself does not think this.

I happen to think that the way the Gospels portray Jesus is exactly the way Jesus was — a literary figure, a creation of theological imagination. I also read current scholarship demonstrating that the NT models of oral transmission either have no counterpart in reality or are inconsistent with the evidence in the Gospel texts. I am also reading current scholarship that demonstrates the logical fallacies that have underpinned the form and redactional criticisms that have been the basis of many HJ reconstructions. Hoffmann does not appear to be up to speed with what his happening in his own field.

For the critic, the “unbeliever,” the mythicist, the gospels are simply not telling the truth or so packed with lies that it is a waste of time sorting out the true from the false, the plausible and the perhaps. . . . .

Again this is nonsense. It is the historicists, not the mythicists, who say this. It is the job of the historicists to try to sort out the “historical kernels” from the “mythical accretions” in the Gospels. Some historicists themselves say that it is a waste of time trying to sort out the true from the false. So we have Crossan, Spong, Le Donne, Allison now arguing that we should accept “general impressions” or “something in between” rather than any specific, concrete details about the life of Jesus (except, of course, his birth, baptism, preaching, confrontations, disciples, death, ensuing “easter experiences” of his followers . . . )

The mythicist arguments that I read hang on the argument that the Gospels are not full of lies or hiding some reality, but are exactly what they appear to be and can be demonstrated to be — theological tales adapted from other theological tales. The mystery and secrecy is a problem that is generated by the assumption of historicity. Don’t forget the parsimony.

My own argument is a bit different. It does not begin with a sacred text but a religious artifact dating from the first century of the common era. It is a story about a man named Jesus the Nazarene who was a healer and magician, and who followed in the radical apocalypticism of someone named John the Baptist, fell out with his Jewish contemporaries over how the law should be interpreted, and was put out of business through a conspiracy between the pharisaic sect and a few law-and-order Roman officials who feared, more than anything else, another Palsetianian revolt. I am not reading between any lines to see this in the gospels. This is the story at the most superficial of levels. . . .

The problem here is that Hoffmann has confused his own Rorschach reading of the Gospels with a “religious artifact dating from the first century of the common era.”

A key detail about Hoffmann’s Jesus is that he supposedly “fell out with his Jewish contemporaries over how the law should be interpreted”. To support this, Hoffmann needs to be able to explain why the words of Jesus that we read in the Gospels are so controversial in the Second Temple Jewish context. To think they were controversial is to bring into the Gospels the anachronistic debates between rabbinic Judaism and Christianity of the second century. Many of Hoffmann’s peers acknowledge this. (But Hoffmann does not seem to have much respect for the scholarship of many of his peers.)

So one of the problems facing other NT scholars (not Hoffmann) is to try to explain why a teacher of such uncontroversial views was crucified.

Hoffmann says he is not reading between any lines to see this in the gospels. Let him quote the passages then that apparently elude his own scholarly peers who are also anti-mythicists. Mere assertion is not argument.

Further, I would like to see Hoffmann justify his other assertions, too. All of them. But let’s begin with Jesus being a follower of John the Baptist. Does Hoffmann have anything other than a rejection of the Gospel narratives to support this view? Every argument I have seen for Jesus being a follower of John the Baptist is based upon a rewriting of the evidence so it is no longer a literary-theological tale. But this process is never justified. It is taken for granted that Jesus was a follower of John the Baptist so the evidence must be re-written. We are asked by the historicists to believe that the evangelists wrote lies about the true history and we can only know what really happened by getting rid of their lies and substituting something they never did say. Pass me the parsimony, please.

Appian tells us that when the slave rebellion of Spartacus was crushed (71 BCE), the Roman general Crassus had six thousand slave prisoners crucified along a stretch of the Appian Way, the main road leading into Rome (Bella Civilia 1:120). As an example of crucifying rebellious foreigners, Josephus says that when the Romans were besieging Jerusalem in 70 A.D. the Roman general Titus crucified five hundred Jews in a day. In fact, so many Jews were crucified outside the walls of Jerusalem that “there was not enough room for the crosses and not enough crosses for the bodies” (Wars of the Jews 5:11.1). History has singled Jesus out of this crowd for other reasons, but crucifixion was so common a punishment for slaves, rebels with various causes, and common criminals that Valerius Maximus scoffs at is as “a slave’s punishment” (servile supplicium; 2:7.12), . . .

Exactly. As some of Hoffmann’s peers have noted, the Romans never did just crucify the leader when they wanted to send a message: they crucified the whole gang. So it’s not mythicists’ fault when they say in unison with certain NT scholars that if Jesus was seen as a threat to law-and-order by any Romans then the disciples would have been crucified beside Jesus.

I’d find Hoffmann more interesting if he could give us any evidence he has been following and engaging with the scholarship of his peers.

In arguing that Jesus is plausible, I am simply saying that the undecorated preacher of rebellion against the enemies of God and the corruption of the temple cult was transformed into the decorated embodiment of the power of God against the power of sin, mostly through the work of one man–Paul–who knew a few stories about Jesus but had never met him in the flesh.. . .

So the really remarkable origin of Christianity was accomplished by the most untypical person of his time. Okay. I think I get that.

From the way the argument goes, I guess Paul could have taken the story of any anti-Roman rebel in Judea of the day and turned him into Christian icon. The only difference would have been that Christians today would be praying to Zacchaeus Christ or Reuben Christ or Judas Christ, or any other typical 3C character of the day. Luck would have it that we got Jesus Christ.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Hoffmann: “This is the story at the most superficial of levels. . . .”

Correction: this is a myth that Hoffmann’s rationalized at the most basic and superficial level. Creating, not the true history of Jesus, but merely another version of the myth.

Neal Godfrey:

“The mythicist arguments that I read hang on the argument that the Gospels are not full of lies or hiding some reality, but are exactly what they appear to be and can be demonstrated to be — theological tales adapted from other theological tales.”

That’s what R.M. Price, T. Brodie, the Dutch Radicals up to their re-discoverer Detering, and many others have shown in perfection. The remaining problem for me as a non-scholar is the addition of a few items (names, places) of ‘real’ history that, so to speak, ‘contaminate’ the tales.

Why not simply “once upon a time …”. But of course that wouldn’t have been a good start for a world religion!

Details “contaminate” the tales? NT scholars who pull out this card to support historicity are only demonstrating how out of touch they are with reality. Read novels — ancient (start with Reardon) and modern — and mythical tales of the past (start with Homer and Virgil), read internet spam mail (e.g. Nigerian emails asking for your bank details; emails pleading for help for a sick child), read accounts of alien abductions, UFO visitations, —- you will see all of these rich with details. Details = Verisimilitude. They are the fundamental tool of the novelists’ craft. I wrote a post on Rosenmeyer’s work on the way ancients were taught the art of creative (fictional) letter writing. Details, especially those incidental details that “seem” to add nothing to the story, are the gems that make it all come alive for the readers.

I seem to recall Carrier himself somewhere spoke of this, too.

I wonder what the Roman reaction would have been to the brother of Hoffman’s Jesus taking over the movement.

HOFFMAN

History has singled Jesus out of this crowd for other reasons, but crucifixion was so common a punishment for slaves, rebels with various causes, and common criminals that Valerius Maximus scoffs at is as “a slave’s punishment”….

CARR

It is Hoffman who has singled out Jesus to be crucified, as he has committed himself to the view that his Jesus was very uncommon, in so much as he was crucified, while his followers were left alone by the Romans for decades at least.

These last four or five posts of Hoffman’s are just the warm-up. I’m sure his evidence will be along any time now.

No doubt. Just like Jesus. He will be here very soon now. So will the Jesus Process and articles from the dozen or so of its members, too.

And this comes from someone who has recently argued that we can know that Paul was addressing the illegitimacy of Jesus when he wrote that Jesus was “born of a woman, born under the law” in Galatians 4:4!

While Hoffman is wildly speculating, why can’t we speculate that Paul is concluding that “the son of man” implies being “born of a woman”? In order to be “the son of man” in the book of Daniel, and in 1Enoch, wouldn’t it make sense to Paul that Jesus was born of a woman? He may not have known what woman but he would know from the Old Testament that the son of man, Jesus, would be a descendant of king David. So, it may be that it was Paul who laid the foundation for an historical Jesus and maybe that was what made Paul’s gospel different from that “other gospel” the Jewish “pillars” were pushing.

Perhaps. But on the other hand we find that Paul at no time refers to Christ as “the son of man”.

And that’s another thing strange that Paul neglects to mention when compared to the gospels. We should start a list of what Paul didn’t seem to know.

Does anyone know what happened to Maurice Casey’s book arguing for the historicity of Jesus against mythicism? That was announced as imminent some months ago and now we have Joe Hoffmann announcing his book that is about to set us all aright. I’d ask around myself but I get the impression Casey and Hoffmann are not on civil speaking terms with me for some reason.

What’s missing from this little tirade is a thing call argument, i.e., conclusions, supported by premises, supported by evidence. Instead, what we get from Neil is mostly some handwaving about what’s current in Biblical scholarship: “His [Hoffman’s] view is surely out of touch with most scholarship that has addressed this question”; “I would like to see Hoffmann himself engage with Pauline scholarship itself, and arguments based upon it, rather than appear to completely bypass it and fault mythicists who take the trouble to take it seriously“; and “I am also reading current scholarship that demonstrates the logical fallacies that have underpinned the form and redactional criticisms that have been the basis of many HJ reconstructions. Hoffmann does not appear to be up to speed with what his happening in his own field.” Peachy, but I don’t care about what you’re reading, and I don’t care if it disagrees with Hoffmann: I care about whether or not Neil can convince me. Merely intimating that some other smart person thinks otherwise won’t do the trick, and your “fans” should know better than that.

It’s touching that you care whether or not I can convince you of anything. Since you care so much I invite you to read my posts where I have made the arguments you are here seeking: Historical Facts and the Very Unfactual Jesus and a series of posts on oral tradition as a flawed hypothesis to explain the gospels. I have many more on both of these topics if you care enough to read them.

“Fans”? I don’t have any “fans”. There are readers of this blog and I don’t know a single one who agrees with me on everything; I know quite a few who disagree with me on major points. Which is just as well, since my own views are always evolving the more I read, learn, engage with others. I think what people like about my blog is that I share the views of others here — others who normally don’t find their way into the mainstream of interested lay people like myself who like to know what the scholars are saying.

Neil,

Dan has a point. Many of your “arguments” amount to assertions that–I know more about Paul than Hoffmann! I know more about Occam’s Razor than Hoffmann! I know more about Second Temple Judaism than Hoffmann! Yet you provide zero evidence of any of this. Rather, you advise the skeptic to check out your interminable archives. Why don’t you just offer cogent counterarguments? But leaving that discussion for another time…

And I have also made some good points and valid criticisms of Hoffmann’s post. If you think Hoffmann has likewise made good points and my criticisms (I said much more than “other scholars think differently”, contrary to Dan’s claim) are invalid or wrong then defend Hoffmann’s post. Point out where my criticisms are misguided and which of Hoffmann’s arguments stand.

Do you really think I have made no valid points against Hoffmann’s post, or that I have said nothing more than “others think differently”? If you do, I challenge you to read beyond Dan’s tirade and read Hoffmann’s post and my response for yourself and make up your own mind. Then come back and address the specific points I made in that post and the questions with which I challenge your and Dan’s criticism.

Get down to the details. None of this hand-waving blanket dismissal stuff that is all you and Dan have managed so far.

Neil,

I’m on my way out but will briefly respond. I certainly read Hoffmann’s piece and thought it superb. It was only out of anxiety that I had been too easily seduced that I ventured to Vridar to endure the howls of protest.

I don’t know why you would start a polemic by driving by a chunky excerpt from Hoffmann’s piece, but OK, let’s move on to your next objection, concerning the following remarks by Hoffmann on Paul:

His ideas were completely unhistorical and at odds with Jewish teaching: he finessed his disagreements into a cult that turned the vindictive God of his own tradition into a being capable of forgiveness.

It “astonishes” you that Hoffmann could really be so “out of touch with most scholarship” on the issue that he would “write such unsupportable caricature as if it were fact.” (Oh dear, I suppose I must be anti-Semitic for viewing Yahweh as a monstrous tyrant.)

Well, what’s this scholarship about, Neil? Could you give us a few references, for example? Or do you assume your audience is already familiar with the current status of Pauline scholarship? Or that your audience is going to give you the benefit of the doubt over an actual New Testament historian like Hoffmann? It’s this sort of thing that left me dissatisfied with your critique.

But I am grateful to you “mythtics” for pissing Hoffmann off to the point where he regularly posts on HJ and is even plotting to write a book. Many thanks!

Yes, I did indeed assume that most readers interested in a discussion like this would be well aware of the mainstream scholarly views on Paul. I thought only fundamentalist literalists today believe that the Pharisees of Jesus’ day were unforgiving, legalistic nitpickers with a vengeful God forever threatening them. Corrections to this archaic view have been well enough published in the popular literature as well as the scholarly. If that is the only point that upsets you about my critique then I am quite willing to do a post to update readers like yourself.

But till then, just look again at the sentence by Hoffmann that you quote:

Paul believed, along with the Pharisees, that their God was incapable of forgiveness? Do you really believe Hoffmann is correct here? Paul’s theology was not about forgiveness but about faith and a life of faith (probably more the “faith of Christ” rather than “faith in Christ”, but that’s another story). The OT teaches from the Decalogue to Malachi about the forgiveness of God as well as his vengeance on those who do not repent and turn to him. All the evidence we have about the Pharisees indicates they were popular among the population generally. They were “the softies” of the religious establishment who did indeed teach the importance of the spirit of the law over legalistic literalism.

But you yourself clearly have a reading comprehension disability if you interpret my statement to mean that it is anti-semitic for anyone think of the God of the OT as a monstrous tyrant.

You saw my post as “howls of protest”? Again, I wonder at your reading comprehension levels. But you wrote in a rush so I look forward to your responses to the specific criticisms I raised.

You will have to explain what you mean by “driving by a chunky excerpt from Hoffmann’s piece.” I was not interested in the first part of his post in which he spoke of his personal views of religion and violence. Do you fault me for addressing the section that interested me?

Neil,

The chunky excerpt is the one you opened you post with,

You got sidetracked on the less interesting point–your objection to the notion that Paul’s generation would have conceived of Yahweh as unforgiving–at the expense of the far more interesting one–Marcion could only rationalize Paul’s theology by relegating Yahweh to second fiddle below a truly merciful God. If God were forgiving enough to begin with why would Marcion be driven to theorize an entirely separate God to account for the merciful nature of Paul’s God? IIRC Marcion dropped the OT from his canon altogether.

I’m interested in these matters, but no, I have no idea what the current consensus of Pauline scholarship is on anything, or the current understanding of the proclivities of the Pharisees, so perhaps this blog is over my head and I should take my leave. It isn’t that I objected to the one thing but that it seemed typical of the impressionistic nature of your dismissiveness toward Hoffmann more generally. You might have added a concrete example or two of the prevailing scholarship if you’re going to accuse Hoffmann of being oblivious, regardless of how sophisticated your readership is. After all, you are not the NT scholar, so the burden is on you to show your ducks in a row.

Didn’t you write this?

Hence my (admittedly lame) snark about Yahweh and anti-Semitism.

Anyway, I don’t want to bore everybody to death so will stop here.

I did get sidetracked away from Hoffmann’s point about Marcion for good reason. Marcion is not Paul (at least I’m not running with the thesis of some that he did write Paul’s letters). What Marcion thought is a separate question from what we read in Paul’s letters as coming from Paul himself. Hoffmann did his doctoral thesis on Marcion, by the way, and his reference to Marcion and other later interpreters of Paul is all about explaining the way the Christ Myth itself evolved. It has no direct relevance to the historical Jesus question itself — despite Hoffmann’s claims to the contrary, if I understand his point.

Marcion’s ideas derived as much from the philosophical notions of his day — the idea of a high God and a lower creator-God is straight from Platonic-related philosophies. Hoffmann knows (or at least wrote in his doctoral thesis on Marcion) that Marcion interpreted the OT literally and saw that God as inconstant, changeable, fickle, sometimes loving and other times vengeful But that’s Marcion’s view, It is not found in Paul’s letters as we know them.

I didn’t realize you were focussed on Marcion in this question. I have been wanting to update this blog with more posts on Marcion — I have already posted several times on this, including references to Hoffmann’s own thesis.

But if Hoffmann is arguing that Paul himself meant or said something because that’s what Marcion thought, then he needs to justify such a method of interpreting Paul. You can’t as a rule take later documents and say that because they interpreted earlier works in a certain way, then that’s what the original authors of those works meant. A late pseudo-Pauline letter even says people were interpreting Paul’s letters in all sorts of wrong ways.

If I appear to be dismissive of Hoffmann’s views it may be because I have had a history of engagement with him and find some of his ideas are fundamentally illogical and out of touch with scholarship. I have challenged him several times and he has never chosen to defend his position with anything other than personal insult.

I take your point, though, that I do sometimes write with assumptions that are not shared by most others. I need to be more careful about that. But if you want to discuss a point then you are more likely to get off to a more productive start if you hold back on the attacks and keep your topics focussed on questions of content.

Yes, I did write the last section you quoted, and it is speaking of a stereotypical view of Judaism in Paul’s day that scholars have since looked back and seen as relic of a pervasive anti-semitism of a previous generation of scholars. There was an assumption that Judaism was bad, inferior, etc etc and Christianity was good, superior etc etc. It was that view of scholarship that has since been widely considered as being yet one more symptom of the anti-semitism of the day to which I was explicitly referring.

Neil,

It’s not that I’m more interested in Marcion (although I’m aware of Hoffmann’s dissertation I’ve never read it), but the whole point is that Paul’s theology was such a dramatic departure from Judaism that Marcion became convinced that the Jewish God wasn’t even Paul’s God. How can you say that’s irrelevant? And so what if (if) Marcion appropriated his scheme from neo-Platonism? He was compelled to do so because Paul’s God was unrecognizable as the Jewish God. Furthermore, what Marcion observed happens to be true.

You yourself confirmed this when you wrote:

Hoffmann knows (or at least wrote in his doctoral thesis on Marcion) that Marcion interpreted the OT literally and saw that God as inconstant, changeable, fickle, sometimes loving and other times vengeful But that’s Marcion’s view, It is not found in Paul’s letters as we know them.

It’s not found because that God isn’t there!

Which (prominent) ideas of Hoffmann’s do you find fundamentally illogical? Mind you, logic isn’t my strong suit, and I can barely add so kindly spare me the Bayes’ Theorem.

This is an interpretation and not a fact. It assumes that Paul’s theology was a dramatic departure from Judaism. (Nor can we say that even if it was, that that’s the reason for Marcion’s beliefs about God.) I recently posted a series on a mainstream (even, I think, conservative) scholar’s analysis of Paul that demonstrated that Paul’s concept of “Christ” was quite within the bounds of normative Judaism of the day.

I think most scholars would say that Luke pre-dates Marcion, and one often reads in the literature that the author of Acts was a close companion of Paul and knew Paul’s theology well. Some scholars even say he knew of Paul’s letters. Many of these will argue that Luke certainly understood or believed Paul to have very mainstream Jewish beliefs so that he could appeal to Pharisees, for example, and claim in his defence that he worshiped God in the same manner as the Jewish Fathers.

Paul himself in his letters appeals to the Jewish God and Jewish scriptures in his arguments. His different interpretations of these scriptures is recognized in the literature as within the bounds of normal rabbinical debates of the day.

The theology that the blood of a martyr should cleanse and forgive the sins of all subsequent generations of Jews — that is, the theology of atonement through blood of a “Beloved Son” — predated Paul and was a doctrine embraced by Second Temple Jews (how many, we can’t say, but we do know that this teaching was acknowledge — that Isaac was literally sacrificed by Abraham and his blood made atonement for the sins of Jews. I posted a series on this by a Jewish scholar some time back.

The notion of a pre-existing heavenly Messiah coming to earth in the flesh and returning again, exalted, to heaven, is also found in some Jewish literature. Again this is a point argued by Jewish scholars themselves.

Paul’s claim to having visionary experiences is another detail that was well-known in Jewish religious practices of the day.

Paul did innovate, but his innovations were not beyond the bounds of what was possible within the Judaism of his day. Otherwise he would not be innovating within Judaism at all but breaking away entirely. And Paul, we understand, maintained his status as a Jew — in the same sense as did Jeremiah and other prophets who pointed to circumcision being of the heart, not of the flesh, and God requiring mercy, not sacrifice, etc.

I recently posted on a book by another scholar (one so conservative that he argues the Gospels are eyewitness testimony of Jesus) who argues that the very idea of a “Son of God” being crucified and also identified with God himself and worshipped was an innovation, yes, but one that was entirely consistent within the Jewish understanding of God of that day.

These are from the works of mainstream and well-respected scholars (Bauckham, Novenson, Levenson et al).

First time at this blog, huh? The whole blog is dedicated to making these arguments. Your comment is the only “little tirade” I see.

@Godfrey I’m skeptical of the author of Luke/Acts. If Luke knew Paul’s letters he certainly took poetic license.

I recently posted a series on a mainstream (even, I think, conservative) scholar’s analysis of Paul that demonstrated that Paul’s concept of “Christ” was quite within the bounds of normative Judaism of the day.

The Messiah was expected to be executed for the remission of sins? I thought the crucifixion was a “stumbling block.” I’ll be interested to look that one up in your archives.

Good night, Neil!

Start with Christ Among the Messiahs Part 7,

Check also the Levenson series on The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son. Especially one of the concluding posts: Jesus Supplants Isaac — the Contribution of Paul.

And most recently, Could a crucified Jesus be identified with God?

No, I’m not saying that Jews generally expected the Messiah to be crucified. I am saying that the Jewish ideas about God and the Messiah and Son of Man and atonement sacrifice were all consistent with the way Paul interpreted the scriptures. Paul was working within Jewish understandings and belief systems to innovate. He did not depart from Judaism, he innovated within Judaism. See Novenson.

Second Temple literature testifies to some Jews believing in a divine figure who lived from eternity, became flesh and then returned to glory in heaven.

Paul’s concepts were not alien to Judaism. They were certainly innovative. His inclusion of gentiles through the faith of Christ was innovative, and no doubt many Jews disagreed with him, but they disagreed with him as they would disagree with other Jews who came up with various interpretations of their scriptures — but who nonetheless remained within the general orbit of Judaism.

Well, thank you, I’ll check those out.

Paul was working within Jewish understandings and belief systems to innovate Right, he wasn’t a Pharisee of Pharisees for nothing. No need to reply and thank you for taking so much time to respond to me.

Also have a look at my latest post where I did get around after all to citing the reasons I believe Hoffmann is out of touch with modern scholarly views on the nature of Judaism and Pharisaism of Paul’s day — http://vridar.wordpress.com/2013/01/17/pharisees-and-judaism-popular-caricatures-versus-modern-scholarly-views/

Curious: While I have taken to heart criticisms that I have left some readers mystified over the substance underlying one or two of my points, and have duly responded by highlighting the logic and validity of my post, linking to posts where I have earlier defended my claims, and even added a new post to further substantiate one of my points, — while I have been busy doing all this, has any one of my critics thought to ask Hoffmann to substantiate his claims and to respond to my specific criticisms of his post?

Why don’t you, Neil? They’re your criticisms, after all. Or are you persona non grata at The New Oxonian.

Even if I objected to Hoffmann’s piece (and I don’t; I loved it) I wouldn’t post over there. I’m too afraid of Steph.

I was intending my comment to be a challenge to others generally, including Chris, and others who regularly fault criticisms of the posts of Hoffmann apparently coming from mythicist sympathizers. My point was to draw attention to the contentious nature of these criticisms against posts on this blog — that is, they are not interested in furthering discussion or analysing the issues raised, but in personal and ideologically driven attack. It makes no matter that I answer criticisms from them. They will simply move on to find some other point to fault. They are not interested in genuine intellectual inquiry.

Even ideologically-driven snipers can be interested in genuine intellectual inquiry!

I myself don’t care whether Jesus was myth or man, but I want to see a good argument.