William Wrede’s The Messianic Secret

Part 6: “The Self-Concealment of the Messiah” — Demons (cont’d)

This unit continues Part 1, Section 2 (p. 24) of Wrede’s The Messianic Secret.

Revealing and Concealing

As we have seen, Wrede agreed with the critics of his day that Mark’s Jesus seems to be intent on keeping it a secret that he’s the messiah. Yet, right next to the commands to silence, we find testimony to the fact that Jesus’ fame spread far and wide.

And he charged them that they should tell no man: but the more he charged them, so much the more zealously they proclaimed it; (Mark 7:36, KJV)

Similarly, the disciples seem to alternate from ignorance to knowledge and back again. Wrede’s concern is to discover where this motif comes from. Is it purely a literary convention, or is it historical? If it is a literary motif, was it present in his sources or is it a Markan invention?

By examining the various manifestations of the Messianic Secret, perhaps we can discover its roots and significance. Ultimately, thought Wrede, such knowledge may help us reveal authentic traditions of the historical Jesus.

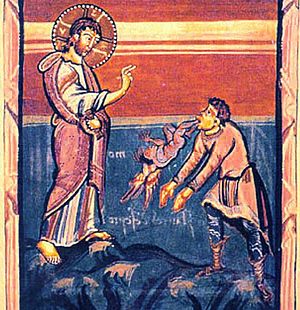

Exorcism and the Messianic Secret

The exorcism stories in Mark provide two distinct aspects of the Messianic Secret. First, obviously, are Jesus’ commandments of silence. A more subtle, secondary aspect is the spiritual rapport between Jesus (now endowed with the pneuma) and the unclean spirits. In other words, the fact that the demons know exactly who Jesus is simply by being nearby, or as Wrede puts it:

A direct rapport exists between him and them; it is not tied to any earthly means of communication. Spirit comprehends spirit, and only spirit can do so. For this reason, the idea that Jesus’ messiahship was a secret is not to be found merely in the command to be silent but is already independently present in the circumstance that the demons know about him. Their knowledge is secret knowledge. (p. 25 — emphasis mine)

Demons detect the proximity of Jesus and immediately know who he is and what his presence on the earth means — namely, that they’re in imminent danger. Further, while they can’t help being terrified by the presence of Jesus, they are “magically drawn to him.” (p. 26)

Essentially fiction

As we said earlier Wrede hoped that a careful examination of Mark’s tendencies (foreshadowing both form and redaction criticism) would help us discard the mythic or legendary husk and reveal the historical kernel. So, in the author’s estimation, can we accept the exorcisms in Mark as historical? Wrede painstakingly works out a complete argument that takes several pages — from p. 25 to 34 — and finally declares, “No.”

To the consternation, no doubt, of evangelicals, apologists, and today’s timid scholars who continue to pretend that supernaturalism is a viable option, Wrede immediately rejects the idea that demons exist and that they can possess human beings. So, if we’re dealing with some nugget of actual history, what is it?

The critics naturally cannot take Mark’s items of information in the sense they originally had. What do they put in their place?

Here is what we find held to be the kernel of these stories. Those who were mentally ill will have been disquieted by the presence of the one who was pure and holy, and will have called on him to leave them in peace. Thereupon, quite understandably, a surge of power will have gone out from the pure personality of Jesus, in all his intimacy with God, to take effect upon the deranged psyches of the diseased. This view is a wholesale abnegation of the object of scientific study and an illegitimate restatement in the modern key of ethics. . .

In cold prose this means that Mark’s account must rather simply be stating that on numerous occasions victims of hysteria or people otherwise mentally disturbed addressed Jesus as Messiah when he was still totally unknown as such. (p. 27-28 — bold emphasis mine)

In short, Wrede agrees with the critics of his day who brushed aside superstitious belief in demons; however he parts company with them on the idea that Mark’s possession stories could be explained by psychological phenomena. (Recall that at the time he was writing, we were on the tail end of the age of rationalism, in which scholars dreamed up naturalistic explanations for miracles, presuming that the gospel writers were honest witnesses who simply misunderstood what they saw.)

He grinds on, page after page, until at last he admits:

This debunking is almost too sweeping. But it was necessary to show that psychology, to which an appeal so often is made, is not and cannot here be helpful so long as our starting-point in regard to the Gospel is the recurrence of these incidents. (p. 31)

For Wrede, the formulaic repetition of the stories is the key — the unmistakable sign that we’re dealing with legendary material. And even if we can whittle the stories down to a single prototype from which Mark derives the rest, we really haven’t gotten anywhere.

Here the “kernel” does little for us. We simply do not see how the overall view of Mark is supposed to have been formed from a real incident or how a typical and significant feature could have grown out of an isolated peculiarity. By contrast the idea or notion held by the narrator or by others who were his predecessors does do a great deal for us. It explains the one circumstance just as well as the many and the many as well as the one; for if in Jesus’ encounter with demons we are dealing with the intercourse of supernatural beings, the idea that the spirits know him is already directly contained in this. It does not even need to be deduced.

I therefore conclude that these features are to be deleted from the real history of Jesus. Their very regularity is what makes them suspicious and betrays their origin. If we are anxious to find here a scanty remnant of history then we have to support the Markan account at our discretion to make it tolerable; but in itself it remains uncomprehended. If we give up the history we have the account entirely as it stands and find it in the supernatural view of the author — which indeed amounts to what is historically impossible — a direct way of understanding the whole. (p. 33, bold emphasis mine)

By definition, Wrede means to say, the modern study of history is a scientific endeavor; hence it must explain events naturalistically. If we cannot explain events by naturalistic means, then we’re probably dealing with myth. Of course, everyone studying ancient history other than the New Testament would argue the same thing. Scholars might contend that there was a historical Gilgamesh, but they would not insist that “we can’t say for certain” or “we must suspend judgment” as to whether he was two-thirds divine.

Wrede’s misinformed critics

As you might expect, evangelicals are scandalized by Wrede’s conclusions about demons being mythological. How dare he cling to such outrageous, indefensible, naturalist presuppositions?! While researching this subject online, I came upon many papers, essays, posts, etc. by apologists who set about to “debunk” Wrede. Here’s something you can do for fun when you have some time to waste. Search for the term “so-called Messianic Secret” in your favorite search engine. Then sit back and enjoy the mind-twisting prose of the apologists.

One core, foundational element of Wrede’s argument that most evangelicals and even many “real” scholars get wrong is Wrede’s understanding of the origin of the Messianic Secret. Heikki Räisänen in The ‘Messianic Secret in Mark’s Gospel writes:

According to an astonishingly widespread and persistent misunderstanding, Wrede regarded Mark as the originator of the ‘messianic secret’. [Räisänen gives several examples in a footnote.] However, Wrede himself says quite explicitly that the theory that the messianic secret was a Markan creation would be a ‘quite impossible idea‘. If it were a (new) concept in Mark, then Mark would have undoubtedly carried through his theory more consistently. . . The idea is already there [in the tradition]. ‘Mark is already under its sway, so that we cannot even speak of a Tendenz‘. [Wrede, p. 145] It is thus a question of a pre-Markan idea which dominated fairly large (though not necessarily very large) circles. (Räisänen, p. 44-45 — emphasis mine)

Here are some examples I happen to have at hand for your reading pleasure. The first is from James D.G. Dunn in his 1970 paper, “The Messianic Secret in Mark” (warning: PDF):

The Messianic secret is nothing other than the attempt made by Mark to account for the absence of Messianic claims by Jesus Himself. (p. 93 of the Journal/p. 2 of the PDF — emphasis mine)

[Note: Dunn is the first English-speaking scholar I can find who called William Wrede “Wilhelm.”]

Richard Longenecker wrote (in the Evangelical Quarterly, edited by F.F. Bruce) in his 1969 essay, “The Messianic Secret in Light of Recent Discoveries” (warning: PDF):

It was William Wrede who in 1901 first established the thesis that the reticence of Jesus to declare himself openly a Messiah is a Marcan device . . . What differences there are among advocates of this position [i.e., that secrecy was a post-Easter invention] have to do mainly with the refinements of Wrede’s thought regarding the specific purpose of Mark’s fabrication . . . (p. 207-208, emphasis mine)

As recently as February of this year we can find scholars repeating this misunderstanding of Wrede. Over on the Patheos website, Alyce M. McKenzie, the George W. and Nell Ayers Le Van Professor of Preaching and Worship at Perkins School of Theology, Southern Methodist University, wrote in a post called “Blessed to Be a Blessing: Reflections on Mark 1:40-45“:

This is the first time we encounter the “Messianic Secret” in the gospel of Mark. The so-called “Messianic Secret” was a theory proposed by William Wrede, a German Lutheran Theologian in 1901. It refers to the motif of secrecy about Jesus’ Messianic identity found primarily in the gospel of Mark. Wrede’s theory was that it was the creation of the evangelist to explain why Jesus was rejected and put to death. More recent scholarship offers a number of reasons why the “messianic secret” may have come from Jesus himself. (emphasis mine)

[Incidentally this “more recent scholarship” is pretty much a regurgitation of apologist denials of Wrede that date from the 1910s.]

They don’t read Wrede

I wish I could say that these examples were isolated cases, but they are, unfortunately, just the tip of the iceberg. I can only conclude that scholars do not read Wrede. They may skim his work, but I think it more likely that they simply read what other scholars have written about Wrede and the Messianic Secret. On reflection, I can’t say I’m surprised by this revelation. They don’t read Wellhausen. They don’t read Bultmann. So why the hell should they waste their precious time reading Wrede — especially if nobody is ever going to call them out on their blunders?

Finally, please take note that this misunderstanding of Wrede is not some minor, inconsequential detail. Wrede believed some of Mark’s sources contained the references to the Messianic Secret, and that the evangelist (somewhat clumsily) put those stories side by side with stories that did not contain such references. Failure to comprehend such a fundamental detail means (1) they haven’t read Wrede (as we’ve already said) and (2) that they’re struggling against an argument that they neither understand nor care to take the time to understand. I wouldn’t even call it a straw man, because I’m convinced they are working from blissful ignorance and not malice.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“And he charged them that they should tell no man: but the more he charged them, so much the more zealously they proclaimed it; (Mark 7:36, KJV)”

So not a lot of obedience to the Messiah, then.

JW:

You’ve hit on the construction of “Mark’s” ironic theme. Jesus instructs the Disciples to tell everyone about his Passion but they tell no one. Jesus tells non Disciples not to tell anyone about his Teaching & Healing Ministry but they tell everyone. But getting back to Wrede:

“The idea [Messianic Secret] is already there [in the tradition]. ‘Mark is already under its sway, so that we cannot even speak of a Tendenz‘. [Wrede, p. 145] It is thus a question of a pre-Markan idea which dominated fairly large (though not necessarily very large) circles. (Räisänen, p. 44-45 — emphasis mine)”

Well Jesus, who could have possibly written before “Mark” and had a primary theme that the significance of Jesus’ Ministry should not be mentioned and the significance of the Passion was not mentioned at the time it happened so that the secret of it needed to be subsequently revealed.

Joseph

Joe: “Well Jesus, who could have possibly written before ‘Mark’ . . .”

Say what?

JW:

One of the strangest/bizarre/macabre things about C-BS is that in looking for possible sources for “Mark” they keep ignoring the only extant significant Christian author before “Mark” and hypostulating non-extant sources. Hopefully the El-e-Paut in the house is now noticeable to you.

Joseph

This post prompted me to consult the book Jesus the Healer: Possession, Trance and the Origins of Christianity by Stevan L. Davies. It’s a radical departure from the conventional wisdom in its explanation of Christian origins — I’ve discussed it briefly in a couple of posts here already. Davies cites scholarly research into the phenomenon often referred to as “demon possession” and healing/exorcisms. We learn a lot about the social-psychological context of these experiences. It was published 1995. One would have expected some discussion of Wrede’s argument in such a book, if only to justify a departure from Wrede’s arguments. I do not recall any discussion of Mark’s narratives as literary artefacts — which must surely be the starting point of any analysis. But Wrede’s name appears nowhere in its seven page bibliography.

To understand Wrede’s Messianic Secrete one must recognize the history of origins for the period 30 CE – 65CE, before Christianity, before the Gospels, even for the earliest decade before Paul. It’s the apostolic period of post-execution Jesus traditions: two denominations each with their own distinctly different understandings of Jesus. First, the Jerusalem Jesus Movement, beginning with the key disciples purposing to again take up the teachings of Jesus. This was soon followed by a group of Hellenists Jerusalem Jews who, with their traditions of dying and rising heroes or gods, took up the notion that Jesus significance was the salvific effects of his death for mankind’s sins which abrogated the Torah. This was deeply abhorrent to the Jesus Movement viewed as a serious misunderstanding of Jesus and treason for Temple authorities. The Acts story of the stoning of Stephen one of the Hellenist group, seems to tell of an insurrection put-down by Jewish authorities, driving the group out of Palestine. Here Paul is introduced participating as a Temple sympathizer holding the garments of those casting the stones. The group fled to Damascus. Next we find Paul as persecutor pursuing the group having his “vision” experience on the road to Damascus, leading to his conversion to this group, from which he received his Christ kerygma. Paul takes his new found gospel to the Gentile world beginning in Antioch to effectively sever knowledge of Jesus and his teachings from his Jewish roots. As Reimarus, the father of the quest for the HJ said it: ‘Search the New Testament Scriptures and see if Christianity was not based on an historical mistake.” The mistake being Christianity was based on Pauline kerygma of the salvific effects of Jesus death and resurrection, rather than on the Jesus Movement with its teachings of Jesus.

Now to Mark’s Messianic Secrete: Mark the Gentile author was proclaiming the Pauline Christ myth over against his opponents, the Jerusalem Jesus Movement led by the key disciples with their sayings of Jesus, Mark fashioned his secrecy motif to deliberately denigrate the disciples to say they were stupid, they just did not get who Jesus really was. He was the Christ the Son of God, Jesus knew it, even the most unlikely, the demons knew it, certain women knew it, but Jesus said kept it a secret.

JW:

So you have taken my Cryptic (pun intended) subtle reference to Paul and fleshed it out into a Gospel narrative about Paul’s creation of Christianity. As Yeshu Barra said, “Sounds like Deja Jew all over again.” We are on the same page. Q than would be the work of historical witness to Jesus and the Disciples. “Mark” deliberately avoids Q because it represents emphasis of Jesus’ Ministry and as much as anything, it is what “Mark” is reacting to, the idea that it was Jesus’ life that was important (as opposed to his death).

Joseph

“By George, I believe you have got it!” Seriously JW I commend you for these precise insights, putting us here on the same page. See my comment 2. “A viable solution to the Jesus Puzzle – -” to: 15. Earl Doherty’s Case Against Mysticism – Pt. 15. You may find it to be of interest.

Why didn’t Jesus often “plain”ly proclaim himself Christ, or God? Why does he 1) mostly instead, just ask others, “who they say” he was? Or 2)at most why does he only speak very ambiguously about a future “Son of man”? OR finally: while does Jesus 3) even tell his followers not to tell anyone that he was the Christ? While 4)in the NT only deeply flawed persons (including Peter, Mat. 16.23), persons who are “unclean,” or Gentiles, or who have demons – say he is Christ.

Why didn’t Jesus make his godhood more plain? Wrede seems to suggest he wanted it to be a secret. The most likely reason: for a Jew to say he was God on earth, or the Christ, was heresy, or out of keeping with other Jews. Therefore, Jesus wanted to keep this a hidden secret. Though? Since scholarship today often suggests that Jesus himself, was “not conscious of being anything other than a good Jewish citizen”? I would suggest related to all this, that perhaps the best explanation, hinted at above, is this: Jesus did not simply and unambiguously say he was God, or “Christ” … because Jesus HIMSELF simply did not regard himself as God, or Christ, or Messiah.

Jesus they say in current scholarship, was “not conscious” of himself as anything more than a good jewish citizen some say. Which would explain why he told others not to tell anyone he was the Christ. Why only deeply flawed and evil people, said to have “demons,” or demonically false ideas, called him Christ. It was not just because – as Wrede seemed to say – that Jesus wanted to keep it a “secret”; it was because Jesus himself did not believe it. And did not want his followers to say that, or believe it either.

High irony, indeed.

Brettongarcia: “Wrede seems to suggest he wanted it to be a secret.”

No. Wrede first points out that both kinds of traditions exist in Mark: (1) Public fame spread far and wide, culminating in the “Hosanna!” entrance into Jerusalem and (2) the secrecy motif with commands to be silent along with hidden (parabolic) teaching. Then he tries to develop a coherent theory to explain the existence of both.

So which of these traditions does Wrede think is authentic? Or is none of it authentic? You could always read Wrede and find out for yourself, or you can stay tuned for further posts on Vridar.

Personally? I do see the Bible and/or Jesus, having two main levels of meaning in then. 1) The first, for “child”ren, assures us that our leaders are great. And tells simple readers without good judgement on their own, to just obediently, faithfully follow our leaders, our god, without asking too many questions. But 2) then there is a second, rather hidden layer. WHich appears hidden; but opens up for anyone who can see it.

What do I see in the second level? At that level, the illusion of such perfect authority in our leaders is dispelled. Those who can read the text themselves carefully are allowed to see for example, that 1) even Jesus himself was not absolutely certain he was the Christ. In fact? 2) We can even see Peter making errors so serious, that Jesus calls the founder of the Church, “Satan,” in Mat. 16.23.

Not sure what two levels Vridar and Wrede and their Christ will end up with. But those are the two conflicting messages, the two levels, that I current see in the text of the NT. The first one of course, was made deliberately obscure to children; who need to be told to faithfully follow their leaders. While the more questioning level, is deliberately made obscure; and therefore accessible only to a knowledgeable and responsible adult reader. Who alone could be expected to deal with that level responsibly.

Correction: “The first one, was deliberately made obvious, and easy to pick up; so simple people needing guidance would see it; since they need to be told to “faith”fully follow their leaders, lacking judgement on their own.

There indeed were two kinds of traditions, each with its own distinctly different understandings of the significance of Jesus during the period 30 CE – 65 CE. Accoding to the best understanding of the Guild of NT Studies: the first the Jerusalem Jesus Movemenmt initally led by the key disciples purposing to agaiin take up Jesus’ sayings, soon followed by a group of Hellenists Jews, who with their traditions of dying and rising heroes or gods, took up the notion that the significance of Jesus was the salvific effect of his death and resurrection. Paul joined this group taking their notion as the basis of his kerygms. By taking his kerygma to the Gentile world, meeting with great success, this had the effect of severing Jesus from his teachings and his Jewish roots, becoming the context of the writings of the NT, thus the source of Christianity. All too soon, as winners in the struggle for dpminance, they could declzre the Jesus Movement heressy to effectively remove it from the pages of history. See Ed Jones – A viable historical solution to the Jesus Puzzle.

Ed: I’d say you are expressing here, something very important. You are outlining the today most widely- accepted view of Christianity, in the field of religious study. Which sees it as a two-part process. Suggesting Christianity 1) began, in Jesus, with a typically Jewish movement. But 2) then Christianity was changed after Jesus died, by Hellenistic Jews. Changed into a more spiritual, metaphorical idea.

As part of this currently-prevailing schema it is said for example, that Jesus was not so much Christian in the modern sense; he was more simply Jewish. And as part of this: when he promised a “kingdom,” he was simply promising a real, material, physical kingdom on this earth, like the kingdom of David. Whereas – as it is now apparently thought by most religious scholars – it was only later, that more Hellenized or Greco-Roman influenced Jews – like Paul – saw that the promised material kingdom had failed, and did not appear. Jesus was killed; and though he was briefly resurrected, he was said to have disappeared into heaven after 40 days. While Jerusalem remained a city occupied by Rome. And so, given the failure of the material kingdom? Later Hellenized Jews began to modify the original promises.

Clearly the traditional promises of Judaism – for a real, material, physical kingdom – had failed. Jerusalem was not a conventional earthly kingdom, under the control of the Jews, or of a son of David; but was under control of Romans like Pontius Pilate. And so, the traditional “kingdom” having failed? What could be done to rescue the credibility of Judaism, and its promises? Here the clever Greeks (and Romans for that matter), managed to “come to the rescue.” Suggesting there was a kind of salvation, even in such a material defeat. As these Hellenized Jews, decided to turn it the old promises of “kingdoms” and so forth, into spiritual metaphors. This second wave of Christians, began to turn the old Jewish promises, into mere metaphors for mental or spiritual transformation: we might not get a real, material “kingdom” after all, immediately. But it was now said, when we convert to Christianity, to its ideas of meekness and mildness, our mind or spirit is transformednd. A we enter at least a metaphorical “kingdom” of the enlightened, of the mild, civilized citizen.is is

This would be my restatement and amplification, of what you have noted. Your outline of what I think is in fact, the increasingly dominant model for the evolution of Christianity, in much of the scholarly world: 1) a first, rather Jewish Jesus, promising a literal, earthly kingdom; followed by 2) the modification of the very Jewish Jesus, by Hellenized followers. Or as I would specify, later, more Platonistic, Hellenized, Greco-Roman followers. Who changed the thought of Jesus, as some say, by over-spiritualizing, over-metaphoricalizing it.

I think you are outlining the implicitly prevailing two-phase model of the evolution of Christianity, among scholars. By the way, for a long time of course, the second phase prevailed. For a long time, until this very day, our more spiritual churches have often taught that 1) the early, more purely Jewish movement, was in effect too materialistic. (And even ” too Jewish,” as spiritual anti-semitists said.) While 2) it is only the second phase, following the “spiritual” “kingdom,” that is the true and best Christianity. And so indeed, here the Bible was read in a related two-part schema: 1) for its literal, physical meaning, but then over and above that it was said, 2) its “higher,” metaphorical, spiritual message. Where the “Kingdom” was turned into a metaphor for spiritualization, say.

So you are basically right. There are dozens of seeing Christianity, as a two-part development. Including your own model … which I think encapsulates the core of current thinking. But ultimately, I’d suggest, they all relate to this vision: of a 1) rather more materialistic vision, of perhaps Jesus himself; followed by 2) a (rather too?) spiritual or metaphorical version of the original promises.

Dr. Goodman, Apologies for the delay, I am particulary impressed with your gracious reply. Here at Vridar I am most often odd man out in Mythicists’ blogsphere and thus ignored. I am surprised to find you here. You may find my comment: A viable historical solution to the Jesus Puzzle to be of interest. With Dr. John H. Elliott, University of San Frisco I reconstruct orgins of Jesus traditions for the period 30 CE – 65 CE, before the Gospels, before Christianity, the period of the two beginning denominations – to follow Reimarus challenge: “Search the NT Scrriptures and see if Christianity was not based on a historical mistake”. This may be somewhat different from your two level take, but I do find it to be cricial. I hoe to find the opportunity to take this up with you if youhave the interest. In any case many thanks for your positive reeply.

Hi Ed, you say you are ignored here. I suspect you have been more privileged here than in many other sites. How many have given you your own page for dialogue? Yes, I understand your argument, have engaged with your points, and I understood that we simply have to agree to disagree. Having reached that point nothing can be gained by continuing to repeat our respective positions.

I did not understand this sentence: “This view is a wholesale abnegation of the object of scientific study and an illegitimate restatement in the modern key of ethics. . .”

What “object of scientific study” is “abnegated” by the view that “surge of power will have gone out from the pure personality of Jesus, in all his intimacy with God, to take effect upon the deranged psyches of the diseased”?

How is this view non-compatible with the one Wrede finds legitimate, according to which Mark’s account “must rather simply be stating that on numerous occasions victims of hysteria or people otherwise mentally disturbed addressed Jesus as Messiah when he was still totally unknown as such”?

More importantly:

“For Wrede, the formulaic repetition of the stories is the key — the unmistakable sign that we’re dealing with legendary material”–

Does this argument seem convincing to you? Are you ready to defend it?

I find it rather weak (in your reconstruction, at least). If there were no repetion in the cases of illnesses and cures, medical science and practice based on it would have been impossible.

You’re doing great job in exposing Wrede’s theses (and their misunderstanding by his critics). I would welcome you spelling out in more details (and, ideally, also assessing) his arguments for those theses.

Arkadi: What “object of scientific study” is “abnegated” by the view that “surge of power will have gone out from the pure personality of Jesus, in all his intimacy with God, to take effect upon the deranged psyches of the diseased”?

For Wrede, the praxis of history is a scientific endeavor. And just like any other branch of science, if you resort to a supernatural story, you have failed. Explaining the appearance of a rainbow as “God’s war bow placed in the clouds” is neither scientific nor an explanation.

Let us suppose that the narrative in Mark is based on historical events. (Recall that at the turn of the century, most scholars had come to believe that Mark was the earliest gospel and that it was essentially historically accurate.) The rationalists of Wrede’s time tried to explain the phenomenon of demon-possession as a manifestation of psychosis. In fact, it does seem that many people in ancient times who were thought to be possessed by demons were instead probably schizophrenic or perhaps had severe epilepsy.

But that doesn’t explain their ability to detect Jesus’ true identity as “the Holy One of God.” This business of a “surge of power” from the “pure personality of Jesus” is what today we would call psycho-babble, the kind of meaningless claptrap you get from Deepak Chopra.

Arkadi: How is this view non-compatible with the one Wrede finds legitimate, according to which Mark’s account “must rather simply be stating that on numerous occasions victims of hysteria or people otherwise mentally disturbed addressed Jesus as Messiah when he was still totally unknown as such”?

In this case (re: “In cold prose . . .”), Wrede is refocusing our attention to what Mark actually wrote. In other words, if the rationalists are right and the demoniacs are mentally disturbed people, then Mark is saying that these deranged fellows somehow recognized Jesus as the Christ when nobody else around them even suspected it. We must therefore conclude that rationalizing demon possession in the gospel of Mark as some sort of psychological issue does not help us get to a satisfactory naturalistic answer, because it still doesn’t explain how they knew what they could not have known.

Arkadi: “For Wrede, the formulaic repetition of the stories is the key — the unmistakable sign that we’re dealing with legendary material” – Does this argument seem convincing to you? Are you ready to defend it?

Yes and Yes. Wrede is foreshadowing redaction criticism.

Arkadi: If there were no repetion in the cases of illnesses and cures, medical science and practice based on it would have been impossible.

Wrede is not talking about the repetition of action, but the stereotyping and repetition of literary tropes. It isn’t repetition for the sake of experimentation. Rather, it is a formulaic, literary process that is a strong clue in redaction criticism that we are dealing with a theological theme the author is trying to impress upon the reader, not the description of real events. In short, Mark’s exorcism stories are theological object lessons, repeated for effect, usually following the same established pattern and sometimes using the exact same words.

Tim:

“Mark’s exorcism stories are theological object lessons”–

I understand that this is Wrede’s thesis. What I’m interested is his arguments by which he proves it.

I understand that one argument is the sameness of pattern and words used in description of the exorcisms.

What I do not understand is how this argument holds against my objection, namely, that it is only natural for a (not too skillful) writer to describe similar events stereotypically,

E.g., I cannot distinguish one bird from another, so if I had a task to describle a sparrow and you name it, I would use exactly the same words.

Did I miss something in the logic of Wrede’s argument?

“But that doesn’t explain their ability to detect Jesus’ true identity as “the Holy One of God.”” —

Ok. But even if their detection of Jesus’ true identity is a literary fiction, their healings by Jesue still might have been actual events, why not?

“For Wrede, the praxis of history is a scientific endeavor. And just like any other branch of science, if you resort to a supernatural story, you have failed.”–

What if someone objects: “well, then the praxis of history (as science), thus limited, is not applicable to the texts reporting divine intervention into history (as the course of events)”?

Every praxis has its limits of application, doesn’t it?

E.g., one does not study consciousness with mathematical methods, applicable in physics, etc.