First let it be clear where I am coming from. This is not an attack on any scholar or the scholarship of theologians in general. It is an attempt to address what strikes me as very muddled thinking in many works about the historical Jesus. That is not a denigration of the scholars in question or the works they have produced. It is forthright attempt to address an assumption or understanding that appears to be generally overlooked. If my views are wrong then I would expect someone somewhere who knows better can point out in a reasoned explanation where and why they are wrong. That would cause me some embarrassment, no doubt, but at least I would be given the opportunity to change my views. I resolved long ago to be prepared to take the consequences of striving to be honest with myself in place of living a lie. But if the only response continues to be ridicule or insult or silent dismissal I will have no reason to think my criticism is invalid.

First let it be clear where I am coming from. This is not an attack on any scholar or the scholarship of theologians in general. It is an attempt to address what strikes me as very muddled thinking in many works about the historical Jesus. That is not a denigration of the scholars in question or the works they have produced. It is forthright attempt to address an assumption or understanding that appears to be generally overlooked. If my views are wrong then I would expect someone somewhere who knows better can point out in a reasoned explanation where and why they are wrong. That would cause me some embarrassment, no doubt, but at least I would be given the opportunity to change my views. I resolved long ago to be prepared to take the consequences of striving to be honest with myself in place of living a lie. But if the only response continues to be ridicule or insult or silent dismissal I will have no reason to think my criticism is invalid.

Often when I read a scholarly study of the historical Jesus I am a little dismayed at the woolliness of the ideas addressed. I have slowly become convinced that very few scholars who have written about the historical Jesus have ever studied what history even is. Very often historical evidence is confused with stories or an assumption that a story must be derived from real happenings.

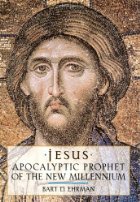

Now I do understand that when Bart Ehrman wrote Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet for a New Millennium (=JAPNM), he wrote it not for his scholarly peers but for a wider public:

Scholars have written hundreds of books about Jesus . . . . A good number of these books, mainly the lesser-known ones, have been written by scholars for scholars to promote scholarship; others have been written by scholars to popularise scholarly views. The present book is one of the latter kind . . . . (p. ix)

The woolliness of thinking about the distinction between the narrative of an event and evidence for a real historical event, and even about the nature of history itself, is a critical consideration given that Ehrman also writes in the same preface:

The evidence itself plays a major role in this book. Most other popular treatments of Jesus rarely discuss evidence. That’s a particularly useful move — to avoid mentioning the evidence — if you’re going to present a case that’s hard to defend. Maybe if you just tell someone what you think, they’ll take your word for it. In my opinion, though, a reader has the right to know not only what scholars think about Jesus . . . but also why they think what they think. That is, readers have a right to know what the evidence is. (p. x)

Since my first draft of this post a new book by Ehrman has appeared (Did Jesus Exist? =DJE) in which he underscores the same fallacies running through JAPNM and adds a raft of new ones. For example, he lists a number of sources that he says historians can rely upon to establish the historical existence of a person while failing to notice that a number of the sources he lists can just as easily be used to argue for the historical existence of several pagan gods and demi-gods. (No wonder he finds they conveniently support the historicity of Jesus!) Equally bad, almost all of them ultimately beg the question of historicity rather than confirm it. I will discuss the logical fallacies inherent in his list in a future post.

What is history?

There are two fundamentals that I learned in about history in my senior history classes.

- The first thing I learned in my history class at senior high school was what history is not. History is not a list of facts, dates and events. A list of events is a chronicle, not history. History is the study of past events, an exploration in understanding those events, the composition of a narrative to convey some story or meaning from those past events. Such a narrative invests the “facts” with interpretation and meaning.

- The second was that when it comes to ancient history historians can only study questions for which we have enough raw material to research. We can’t write a biography of Socrates examining the range of formative influences upon his thinking and assessing how much of his contribution to Greek philosophy was unique to his own genius, for example.

Let’s unpack these a little.

1. What history is not and what it is

The raw material with which historians work is data, say a collection of original documents and manuscripts. The historian reads this data to arrive at meaningful information — that is, learning what the documents say and what sorts of documents they are. From this information the historian understands that certain events happened in the past to produce this information. That is, someone with certain information and certain intentions recorded events in, say, a church register of baptisms. If the historian can verify that a document really is a valid register, then he or she can declare that the information it contains is evidence of an event in the historical past, such as the birth in 1564 of one person known as William Shakespeare.

Other data examined by the historian in order to turn it into meaningful information, may lead the historian to conclude that he or she has evidence that a person by the same name in the same time period wrote plays.

We are talking here about the raw material historians use.

Nothing we have described thus far is “history” in any meaningful sense. It is all just data, information and evidence of facts that happened in the past.

To write history the historian will make use of this evidence and the knowledge thus acquired of what events happened in the past.

If the historian chooses to write a history about the manuscripts of Shakespeare’s plays, he or she will attempt to track down who owned the manuscripts in the past, how they changed hands, how they came to be where they are now, and also study any changes that have been made as manuscripts were copied etc etc etc. The historian is looking for evidence that can be used to piece together a narrative, a story about the manuscripts.

If, however, the historian wishes to write a history about Elizabethan drama, those details will be far less important. Rather, comparisons will be made with the works of other playwrights; political events at the time will be studied; social customs will be investigated. Again, the historian is looking for events that can be stitched together in a narrative. It is the narrative that is the history.

So we see it is not the raw material or the mere events of the past that make history. History is the construction of narratives or explanations of events known to have happened in the past.

History is a study of the past; it is not a chronicle or list of events and dates from the past.

2. The raw materials of the historian

What is advanced as evidence for Jesus are in large part hypothetical sources and “facts” about his life. One can justify an investigation into the origins of Christianity but we hardly have sufficient raw material to study the person of Jesus himself. This is why historical Jesus scholars have manufactured processes they call “criteria” to apply to our sources in an effort to force them to yield “raw facts” with which to write a history or biography of Jesus. The chaotic and conflicting results of these studies is witness to the contradictory nature and fallacies within the criteria and even the process of “criteriology” to “manufacture” the “facts” the historical Jesus scholars want.

I won’t test the patience of readers by repeating here the details. I have addressed them fully in Historical facts and the very UNfactual Jesus: contrasting nonbiblical history with historical Jesus studies two years ago and many times since.

Clearly the focus of interest on “the historical Jesus” addresses the demands of theological, and to some extent broader social-cultural, interests. Scholars have too often, however, compromised valid historical inquiry under pressure of these demands.

Are historians like detectives?

The answer depends. Detectives are called out to the scenes of criminal events. If they discover there was no event at all then those who called them out will have some explaining to do. If the detective studied the crime scene and after seeing the broken window, the muddy footprints, the fingerprints, the ransacked room, the owner of the house lying on the floor badly beaten, and he finally concluded, “Yes, there has been a break-and-enter here and someone has been badly assaulted,” he would probably not be considered the force’s sharpest Sherlock.

On the other hand, if the detective could piece the information together in a way that led to the identity of the criminal and his motive he would have earned his pay cheque.

The latter scenario is comparable to what historians do. They piece the clearly established events together in such a way to create a plausible story that is of some use or interest to others.

Are historical Jesus scholars like detectives?

Bart Ehrman says “we should always think of [the details in the Gospels] as if we were historical detectives” (p. 35, JAPNM).

Historical Jesus scholars, however, spend a lot of time looking for facts about the life of Jesus. They only have a miracle-laced story (appearing in a faith-document) about the baptism of Jesus and no corroboration external to the faith-tradition. So they call upon the Criteria Cavalry to help them out. The criterion of embarrassment steps forward, elbowing to the sidelines his rivals such as the criterion of fulfilled prophecy and the criterion of literary analogy and says, “It would be embarrassing for early Christians to have John baptise Jesus so they did not make up the story: it is probably historical.” Why it would be embarrassing is not always spelled out. Even where it is spelled out the alternative scenarios that would permit Christians to manufacture such a scenario are very rarely considered and weighed.

Thus a hypothetical “fact” is manufactured from a hypothetical premise. This is not good detective work; nor is it good history.

Historians, like detectives, do need to set out the facts before they can begin their work. But manufacturing hypothetical facts from hypothetical premises is not good form. (What historical Jesus scholars are doing is actually manufacturing ideological and social knowledge, a form of propaganda, but this is something to be explored in another post.)

Consider further . . . .

Is Ehrman’s “historical detective” poring through the box of manuscripts or primary sources to find information that will yield evidence of events, evidence of what happened? Or — to set up an extreme example — is this historian, without realising it, simply reading an Agatha Christie novel and fantasising about “being there” as if the words on the page are windows to the real manuscripts, the real data that will yield information and evidence? Isn’t the Agatha Christie only a fiction anyway? It would be nothing but a mind game to pretend it was evidence for a real crime.

But wait on. Am I trying to say the Gospels are fiction? Well, yes and no. Firstly, I believe the valid approach to the gospels is to approach them agnostically. We should not pre-judge them as either fictional or otherwise. I do not argue, and never have, that we should presume at the outset that the Gospels are fiction or that there is no historical basis behind their stories. But neither is it valid to begin with the converse. Surely either proposition must be demonstrated, and until then the question should be held in limbo.

The whole judicial verdict analogy is inappropriate . . . anyway. In the one case, we have two choices, to put a man in jail or not. In the other, we have three choices: certainty of an authentic text, certainty of an inauthentic text, and uncertainty.

A suggestive argument that nonetheless remains inconclusive should cause us to return to the third verdict . . . . The logical implication would seem to be textual agnosticism, but [often a scholar] prefers textual fideism instead.

Adapted from Robert M. Price; Jeffery Jay Lowder. The Empty Tomb: Jesus Beyond The Grave (p. 73). Kindle Edition. With thanks to Tim Widowfield for the quote.

Yet in this particular case Bart Ehrman himself has said that many of the details in the Gospels are “fictional”. No, he does not use the word “fictional”, but he does let us know that we have a right to call them “myths” if we are not oversensitive to the connotations of that word to a mainstream (presumably American and largely religious) audience:

But one thing has remained constant since Strauss. There continue to be scholars — for most of this century, it’s been the vast majority of critical scholars — who think that he was right, not in all or even most of the specific things he said, but in the general view he propounded. There are stories in the Gospels that did not happen historically as narrated, but that are meant to convey a truth. Few scholars today would follow Strauss in calling these stories “myths”. The term is too loaded even still . . . . (p. 30, JAPNM)

But is a myth really just another word for fiction?

For Strauss, the Gospels contain . . . myths. . . . Today, most people understand a “myth” to be something that isn’t true. For Strauss it was just the opposite. A myth was “true.” But it didn’t happen. Of, more precisely (but put rather simply), for Strauss, a myth is a history-like story that is meant to convey a religious truth. That is, the story is fictional, even though it’s told like a historical narrative . . . . (pp. 27-28)

What a load of gobbledegooky double-speak! From this point on Ehrman speaks of “historical inaccuracies” and “Gospel truths”. Ah, how the fear of the target audience clearly has been wagging the scholarly dog — not just in Ehrman’s case but in the case of all scholars whom Ehrman says think the same way.

To be blunt, the Gospels are clearly filled with myths. Fictions. Leave it to the Orwellian theologians who would like to rename these myths as poetic “truths” or “truths” of a religious kind. Are scholars so squeamish about calling the pagan myths “myths”? Do they refer to the Iliad as consisting of mere “historical inaccuracies” or things that did not happen “as narrated”?

Now we know that in ancient historiography we do read stories of miracles and myths alongside genuine historical narratives. But in most of those cases the ancient historians themselves will express some scepticism about the historicity of the myth or miracle, or at least set apart such tales as open to question by the reader. The significant differences between these histories and the Gospels is that:

- we know where the histories originated but we only have guesses about the Gospel origins, who they were written for, by whom and why;

- the histories have at some level clearly independent corroboration while the Gospels do not;

- the histories are written as history genre (hence the expressions of scepticism in relation to the miraculous and mythical) while the Gospels are clearly faith documents of questionable historical validity.

The historian, like a detective, needs to clearly acknowledge the nature of the sources he or she is reading and to clearly understand the implications of their nature. A narrative does not by definition have to derive from oral traditions. Oral traditions do not by definition have to originate with historical events. But historical Jesus scholars so very often don’t write as if they understand this. Mythical tales are not necessarily embellishments of real events. We cannot assess a narrative’s origin properly unless we carefully analyze the full range of possibilities. This is what our court system is designed to do: to test all the possibilities behind the testimonies of various witnesses.

I should add here that the historian of Alexander or Cicero or even of Socrates does not have this problem of reliance upon works that are filled with myths or that we must approach with agnosticism over their fictional or non-fictional status.

- Firstly, they do not rely upon sources that without exception all hail from one singular faith tradition. (At least Albert Schweitzer could see the logical fallacy of relying entirely upon such documents if one seeks to establish credible historical probability. See the final paragraphs in Schweitzer’s Comments on the historical-mythical Jesus debate.)

- Secondly, they do not rely upon sources that ultimately date twenty or more years after the supposed events in question. (The “fact” that Martin Luther committed suicide began to be circulated in hostile circles, according to our evidence, twenty years after his death, and it is because of this twenty year lateness of the appearance of this “tradition” in the record that a staunch Catholic historian insists that this “fact” be ignored and treated as “fiction”.)

Do historical Jesus scholars consistently distinguish between a narrative tale and a real-world event?

Clearly and emphatically No!

To keep with Ehrman as a case-study, we are informed that

Prior to the Enlightenment . . . virtually everyone who studied the Gospels — whether Catholic, Orthodox, or Protestant, or whatever or whichever stripe – understood them to represent “supernatural histories.” That is to say, the Gospels recorded historical events, things that actually happened. (p. 23, JAPNM)

That is true. I fully accept what Bart Ehrman is saying here. The Gospels were for most of our past widely accepted as faithfully recorded history.

So what happened in the wake of the Enlightenment?

The Enlightenment that swept through Europe in the eighteenth century involved a whole new way of thinking and looking at the world. . . . According to these scholars [who were influenced by the rationalistic world-view of the Enlightenment] the miracles of the Bible obviously didn’t happen — since modern people no longer need to appeal to the supernatural the way the ancients did. . . . For such scholars, the Gospels do not therefore contain supernatural histories at all. They instead recount natural histories. (p. 25)

That is, the miracles in the Gospels could be explained by natural means. Jesus did not walk on water: it was night with a strong head wind and the disciples in the boat didn’t realise how close to shore they really were. And so forth. Thus:

Prior to the 1830s, just about everyone understood the Gospels as either supernatural histories or natural histories. (p. 27)

Then along came David Friedrich Strauss. See above. He examined both the natural and supernatural arguments for the miracles, such as Jesus walking on water. If Jesus really walked on water, he was not human like any other human. And if not, there goes the theological basis for Christianity. Was it not only by the shed blood of a deity who came as a true human that we can be saved? Conclusion: the story of walking on water (and the other miracles) was a metaphor to illustrate a spiritual “truth” — that only in Christ or by faith we can rise above all the trials and tribulations of this world. That is, the story was a myth. A fiction. Only those who read theological meanings into it could call it “true”, but of course this meant nothing more than doctrinal “truth”, not historical truth.

Ehrman even compares such stories to falsehoods that are repeated to American school-children as “national propaganda”. Here he cites the story of George Washington as a boy confessing to chopping down the cherry tree. This falsehood serves to teach that the “United States is founded on honesty” as well as to “convey an important lesson in personal morality.” Ehrman explains:

The Gospels of the New Testament contain stories kind of like that, stories that may contain truths, at least in the minds of those who told them, but that are not historically accurate. (p. 31)

That may “contain truths”? Oh come on. It is clear the stories themselves are falsehoods. “Contain” truths? Let’s be blunt again. They are fables that are told to teach lessons that the teacher believes should be taught and that are moral and right and good for everyone. It is a classic case of Plato’s “noble lie”. Be honest! Don’t lie about lying if you’re a scholar. Tell it like it is.

Not “historically accurate”? This is nothing but Orwellian double-speak. That Caesar braved a storm in a small boat might be an historical inaccuracy. But that anyone should walk on water is a myth.

No, we are not talking about “historical inaccuracies”. We are talking about myths as opposed to historical events.

And what is the basis of believing that the Gospels might be records of historical events? Ehrman has effectively told us. Ever since the beginning, certainly “prior to the Enlightenment”, society has believed the Gospels are historical records. Then the primary change that broke in upon us was with the Enlightenment when it was decided among many scholars that they testified of a natural history rather than a supernatural one. The idea that they were “history” of some kind appears to have been too far ingrained to be questioned.

Only with Strauss was their historical character questioned. But Ehrman knows his readers, and the lay and many scholarly readers of Strauss, and that they will dismiss Strauss for this reason:

Before writing Strauss off as a crazed, dismissive skeptic . . . . (p. 27)

Ehrman knows that Strauss offends a world of readers still steeped in some form of religious belief.

The Gospels are still assumed to be some form of record of historical events. And if the most sceptical of scholars concedes this, that scholar can rarely escape the tyranny of the cultural world-view that says at the very least the Gospels were inspired by historical events. Even if they narrate only myths, those myths, it is assumed, were inspired by real persons and happenings.

But it is all assumption.

There are nothing but assumptions all the way down.

There is no evidence.

There are no controls.

It is all belief. Faith. Tradition. Assumption.

Look at Ehrman’s explanation at the conclusion of his discussion pointing out the mythical nature of the narratives of the birth and death of Jesus:

My examples, then, have to do with accounts about Jesus that appear to be contradictory in some of their details. Let me stress that my point is not that the basic events that are narrated didn’t happen. Since these particular accounts deal with the birth of Jesus and his death, I think we can assume they are historically accurate in the most general terms: Jesus was born and he did die! My point, though, is that the Gospel writers have given us accounts that are contradictory in their details. These contradictions make it impossible for us to think that the stories are completely accurate. (p. 32)

Oh dear! Stories of angels appearing and virgin births and the day turning to night at the full-moon are not “completely accurate”? But since they are about a birth and a death and people are born and do die . . . . “I think we can assume they are historically accurate in the most general terms”!!!??

Do I really need to say any more?

Like just about every other historical Jesus scholar I know of, Ehrman simply assumes a story at some level is a record of a historical event in the real world. Sure most of the details are imaginative creations. But no-one can doubt that people really are born (just like Cain and Abel and Methuselah and Achilles and Athena and Dionysus) and really do die (just like Adam and Abel and Methuselah and Achilles and Heracles and Dionysus).

The explanation of how historical Jesus scholars work according to Bart Ehrman in Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium is flawed at the most fundamental levels. In subsequent chapters Ehrman details more minutely the ways he and his peers arrive at “historical details” about Jesus. I hope to address those details in future posts. I will also look at his explanations of historical methods and sources of historical Jesus scholars in his new book, Did Jesus Exist?

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Great summary Neil.

Dr. Ehrman appears unwilling to think the unthinkable.

Maybe one day he will be honest enough to follow the evidence & form conclusions based on that instead of a whole lot of faith-based assumptions.

-evan

In Richard Carrier’s chapter 7 (Was Chritianity Vulnerable to Disproof?) of Not the Impossible Faith: Why Christianity Didn’t Need a Miracle to Succeed, there is a section titled The Problem of Luke’s Methods as a Historian. He said:

I have an even less sanguine view of the Gospel of Luke as a piece of history writing, critical or otherwise. Richard Pervo shows pretty clearly to my satisfaction that the author of Acts was first and foremost a novelist who was only using the history-like prologue as a device to make his novel sound like, well, at least a historical novel. If it was intended to appear to be a novella like a history then that is all it was — a piece of “teach and delight” entertainment cum theological instruction. And the Gospel of Luke is very much, in my view, the same sort of writing.

Compare what Josephus would have thought of it if it were a real piece of historiography: What Josephus might have thought about the Gospels as history.

The prologue is there for show. It is as fictional as the rest of the narrative. Compare Luke’s prologue: historical or historical allusion and The literary genre of Acts: Ancient Prologues.

Luke was a novelist-theologian, not a historian. Not even by ancient standards. Anything that looks historical in his gospel is a literary device, a pretence, an art. The work is a theological novel, a pretend historical novel if you like.

As the last paragraph of your quotation shows, Luke demonstrates none of the genuinely historical style or thought of other ancient historians when it comes to the substance of his tale.

Most historians of religions, especially Christianity, special plead for relaxing of proper principles of historical methodology – they want ancient history to be viewed differently to more recent history in terms of defining primary or secondary sources – most want the gospels or Josephus reference to Jesus, to Tacitus’s references to Christians to be viewed as primary sources, when they are not.

Sure, there are difficulties with finding primary sources for persons of ancient history, but that should not mean redefining principles or procedures – just say that secondary or even tertiary sources are often the best source for characters of ancient history rather than re-define “primary” to suit a bias.

Here is Ehrman trashing the Gospels as sources ‘You have the same problems for all of the sources and all of our Gospels. These are not historically reliable accounts. The authors were not eyewitnesses; they’re Greek-speaking Christians living 35 to 65 years after the events they narrate. The accounts that they narrate are based on oral traditions that have been in circulation for decades. Year after year Christians trying to convert others told them stories to convince them that Jesus was raised from the dead. These writers are telling stories, then, that Christians have been telling all these years. Many stories were invented, and most of the stories were changed. For that reason, these accounts are not as useful as we would like them to be for historical purposes. They’re not contemporary, they’re not disinterested, and they’re not consistent.’

Rather fortuitiously, it turns out the Gospels are ideal historical material for refuting mythicists, while not being at all useful for Christians trying to show that there is some truth in their claims about Jesus.

What are the odds, eh?

Clearly no one here at Vridar has taken even the slightest account of the guild’s present radical reconstruction of post death Jesus traditions. The classic statement of the Scriptural basis for this reconstruction in the words of Schubert M. Ogden: “We now know, given our present historical methods and knowledge, not only that none of the Old Testament writings is prophetic witness to Jesus in the sense in which the early church assumed them to be, but also that none of the writings of the New Testament is apostolic witness to Jesus as the early church itself understood apostolicity. The sufficient evidence of this point in the case of the New Testament writings (the letters of Paul, the Gospels, as well as the later writings of the NT) is that all of them have been shown to depend on sources, written or oral, earlier than themselves, and hence not to be the original and originating witness that the early church mistook them to be in judging them to be apostolic.” Thus to say the writings of the NT are written in the context (authorial intent) of imaging the Christ of faith (the Christ myth), not the man Jesus. From now on all legitimate Scriptural Jesus studies must begin with this indisputable historical fact.

Wrede’s treatment of Mark’s Messianic secrete is making the explicit point that this is Mark’s mythic creation to counter the Jerusalem Jesus Movement with their Sayings Gospel witness to the Jesus of history, the earliest Jesus tradition. The disciples were just dull, stupid, they did not get it; Jesus was the Christ, the Son of God, even the most unlikely beings, the demons, knew it as well as the women at the tomb but they were told to keep quiet. The one source of apostolic witness, Jesus’ disciples just didn’t get it. This is clearly not history, it is authorial intent, the context in which Mark the first Gospel was written, to become the primary source for the later Gospels, hence they are all not Scriptural sources for knowledge of the man Jesus. Merrill P. Miller’s online article “Beginning From Jerusalem –“ takes the majority of present NT scholars to task for following the Acts lead in depicting Jesus tradition origins, failing to take account of present NT reconstruction. Meanwhile the secular critics have their hay day digging up NT grist for their No Jesus.

Ehrman might well make the case that Jesus existed from the writings of the NT. It is clear that this is the limit of his Scriptural source. What his work well demonstrates is that the significance of Jesus, what he was up to, cannot with any certain clarity be extracted from these texts.

Bart claims that if something can be taken apart into previous written documents, historians have to accept them as true.

I guess that if bits of the Old Testament can be dismembered into J,E,D and P sources, then Moses and Noah must have existed.

If your standards for what is to be taken to be historical were strictly applied, many documents and other sources with genuine historical value would be eliminated. So in fact (and contrary to your assertions):

We know a great deal about the origin and intent of the Gospels and must locate them within a specific historical context and among a group of people that communicated the same essential information as the Gospels in the form of letters (a vital source of historical content) — information that was extended in the book of Acts that was written by a man who was very well informed about: (1) what was believed by Christians from the beginning of the movement (Luke’s introduction) and (2) the world around him (indicated in numerous details in the book of Acts).

When we compare the documentation for the rise of early Christianity with the documentation for the rise of other philosophical and religious movements in the ancient world, we see that Christianity’s origin is very well substantiated.

You imply that historians study only ancient sources that “are written as history genre”. But that is not true. They delve into every piece of information they can find, much of which contains what we would call theological convictions. Furthermore, even much ancient history in Greece and Rome incorporates theological perspectives that include providential and miraculous events that may or may not have occurred and may or may not have legitimate historical events at their core.

You incorrectly state that historians never “rely upon sources that without exception all hail from one singular faith tradition”. The fact is, historians are delighted when they are able to get on the inside of a movement that is historically significant, especially when letters are involved and reveal the mind-set of those involved.

These letters were written in access to those who knew Jesus and the generation that followed them. The ease with which these letters, the Gospels, and the book of Acts makes reference to Jesus’ miraculous deeds — especially his resurrection — are surprising. And the power of Jesus’ personality, expressed in his words and deeds in the Gospels are intriguing to scholars. These references and the strong impression Jesus made carry historical implications and cannot be dismissed merely because they imply what is improbable in other contexts.

Finally, you imply that historians do not rely upon “sources that ultimately date twenty or more years after the supposed events in question”. This is simply untrue. Numerous events and historical characters are known only through sources that date far beyond a few decades after the fact.

Because we have sources written within the lifetimes of Jesus’ contemporaries — who were called and trained by him — and by their immediate successors, we may conclude that early Christian convictions are well-founded in events readily recalled and expressed. (In this conviction, many informed historians and theologians have reached conclusions quite different from Barth Ehrman, who you are critiquing.)

Bobby, thanks for your response. I hope we can engage in fruitful exchange.

You wrote:

Two points in response:

1. It is not logically valid to reject a method because we might like the results if we apply it. The validity of a method should be defensible in its own right, not according to the particular answers we would like to see;

2. I do not believe my method would eliminate many historical documents and sources used by historians at all. But it will change radically the way New Testament scholars interpret sources for Christian origins. That is, it will force NT scholars to treat their sources by the same standards and according to the same principles as historians in other fields treat theirs.

I welcome any feedback on this — am I wrong? What documents and sources would really be excluded?

You next wrote:

How much of the “intent” do we “know” about the Gospel of Mark? I emphasize “know” as opposed to “surmise”. On what grounds do we allocate a “specific historical context” to each of the gospels, beginning with GMark? What, precisely, is that “specific historical context”?

You wrote:

You misread or misunderstood what I meant. I certainly have never suggested historians only study ancient sources that are written “as history genre”. Not at all. Of course, and especially in ancient history, they study all artefacts. I have written several posts explaining why NT scholars should study Hellenistic novels, for example. They enable us to understand the genre and motifs and literary artifices of the day and that cast important light on the Gospels and how we must interpret them.

I have not made myself clear to you since you also write:

What I said was entirely correct, surely? All the NT documents are “faith documents”, are they not? And yes, of course! historians are delighted to get their hands on the inside of such a movement! Absolutely. But where is the contradiction that you seem to indicate? Getting to know the mind-set from the inside is worth its weight in gold. But if we are to understand the origins of Christianity we need more than the mind-set of the insiders. We need to see those insiders within their wider context. How else can we know we are interpreting their inside information correctly? We need controls. We can’t just assume that the insider view is the only true and correct one according to our expectations. Some Christians believed that Jesus descended from heaven as a man. Do we assume that this insider view is truly the historical one? Of course we need to ask for the evidence of the dating and provenance of our sources vis a vis the proclaimed activities supposedly external to those sources.

You finally write:

I was quoting, if I recall, a historian when I spoke of the 20 year gap as but one instance of what historians see as the problem of sources not being contemporary with the events described. I certainly do not discount secondary evidence, by the way, but secondary evidence needs to be evaluated differently from primary evidence. But as for the general tenor of you statement, it would be helpful if you gave some examples so we can be sure we are not needlessly divided over quibbles or misunderstandings.

I think I tried to say too much in my last email. I tried to cover too much ground. So taking only one point this time:

There is a problem in what you call “contemporary” and “primary” sources for ancient history.

You state that historians “do not rely upon sources that ultimately date twenty or more years after the supposed events in question.” And in your response to my email, you state that such sources are not considered “contemporary with the events described”.

But sources that close to the events are precisely what ancient historians label “contemporary”.

In his Antiquities, Josephus’ references to Jesus and those who knew him were written over 60 years after Jesus. Yet historians find his statements valuable in reconstructing what occurred in Judea at that time. And on these and other matters, the Antiquities are considered “contemporary”.

Plato’s Dialogues – with their references to Socrates and other historical characters and events – were written well into Plato’s teaching career, a few decades after the people and situations they describe. But the Dialogues are certainly “contemporary historical sources” in the normal sense of “detailed writings by someone close to the facts”.

Though not “contemporary”, other writings that are separated by a century or more from the events they document are usually regarded as “primary” by ancient historians. As examples:

(1) The five major sources for details of Julius Caesar’s career were written between 100 and 150 years after him.

(2) The separation between the life of Alexander the Great and the existing sources for it is between 300 and 500 years.

(3) Extant information about most of the early Greek philosophers and the earliest Greek and Roman rulers was written several centuries after they lived.

I have no disagreement with what you say at all and our differences arise over only technical meanings of primary and secondary.

What I have meant to address in my remarks on historical sources is the reality or fact of something or someone in the past. The discussion has centred on how we know anyone existed in ancient times and attempting to see how our beliefs about the existence of Jesus square with general principles.

Josephus lived at the time of the Jewish War and we have several types of controls that confirm for us that the war he writes about was a “fact of history”. (That does not mean we need to trust everything he says about it, of course.)

While many tend to refer loosely to our earliest sources as “primary”, other historians are more particular and narrow the term “primary” to contemporary — evidence that is located physically at the time and place of the historical event being investigated. With this meaning of “primary” we have to allocate the surviving manuscripts of Josephus as “secondary”. Secondary sources are important and there are some instances where they can actually tell us more truth about a past event than a primary one. But the primary evidence must always be the starting point of study. Thus archaeological studies can help historians correct Josephus’s details.

In relation to your point about the sources of other ancient figures, my argument is covered in older posts such as:

1. Comparing the sources for Alexander and Jesus,

2. How do we know anyone existed in ancient times (Or, if Jesus Christ goes would Julius Caesar also have to go?),

3. Comparing the evidence for Jesus with other ancient historical persons,

4. History as science, not only art,

5. Is it a “fact of history” that Jesus existed, Or is it only “public knowledge”,

6. Historical facts and the very unfactual Jesus: Contrasting nonbiblical hisotry with historical Jesus studies.

Rick Sumner questioned me on some of my comments and there may have been times i overstated my position, but hopefully I clarified or modified some of what I had written in:

7. Historical facts and the nature of history and

8. Charity, suspicion and categorization: exchange with Rick Sumner continued.

Then we are in essential agreement so far. The only disagreement we have is technical:

Some ancient historians believe we have “primary historical sources” for reconstructing some events that occurred a century or more before the source was written. And you think — even though these are our earliest sources with major details.concerning certain historical figures and events — they should be categorized as “secondary”. That’s fully understandable and is only a minor difference between us.

But this means that — by our common understanding of the terms — the Gospels rank as: (1) “contemporary” (as to date) and (2) “primary” (as to quality) for the life and words of Jesus.

On your last point about the gospels, i see it differently. Firstly, if we apply “scientific dating” methods to the gospels then the case for them being second century products is stronger than the conventional wisdom: Scientific and unscientific dating of the Gospels.

But regardless of their date we still have a major problem. We cannot presume the narrative-world of the Gospels is the real world of the authors. The serious anachronisms count against this anyway, but the real problem is that such an argument is circular. We can’t take the story construct and rely on its own testimony that it is a true story. We can’t assume that the authors were writing a true story because we believe they were wanting to write what they believed was a true account because we believe the story is a true account. To see this problem of circularity in another context I have outlined the logic at The Bible — History or Story?

Then there is the question of genre. The only published discussion of gospel genre that i know of that is grounded seriously in genre theory is that of Michael Vines: Vines: Problem of Markan Genre. That presents a very strong theoretical argument for the first gospel being a Jewish novel. On top of that we have the many parabolic/cryptic motifs in Mark that likewise point to it being a symbolic narrative of some kind. Thus comparisons with other literature of the day lead to a strong case that the first gospel was not of the sort of literature that suggests the author had a genuine “historical” interest of any kind.

To sum up: we have no external controls or evidence to give us any reason to think that the narrative world of the gospels had any external reality. A literary analysis of the first gospel — the one that is the foundation of those that followed — strongly indicates that it served no historical function. Scientific dating also puts the gospels to a provenance that is long after the setting of the narrative events themselves.

But the most critical of those above three factors is the lack of external controls. We cannot validly rely on the self-witness of a narrative alone to assume it is historical.

If we want to say that the gospels are contemporary as to date of the events of Jesus we are simply arguing in a circle that there was an historical Jesus to date. How do we know the gospels were written in the generation of Jesus? Some verses in them indicate this is so. How do we know when Jesus was actually dated? The gospels tell us so! Circular.

If we want to say they are the earliest (and therefore best available) sources for the life of Jesus, we must ask how we know there was a Jesus to speak about. Answer? The gospels tell us so! Circular.

In other words, what we have done up till now is let the narrative witness to its own historicity.

There is no validity in that. Always we need some form of external control to enable us to break our circularity.

Now this alone does not disprove the existence of Jesus. But it does leave the question unanswered. Other forms of analysis will be required to answer that question.

One thing at a time, please.

You began by dating the Gospels to a few decades of the life of Jesus. That would classify them as “contemporary” to him. Are you now changing your mind on that point?

If so, let’s deal with one piece of evidence at a time.

Let me add:

I’m searching for common ground. I am asking — at the outset of considering an evaluation of the historical value of the Gospels — that you concede they were “contemporary” documents (written within an acceptable time-frame to be considered contemporary) and that, at least potentially, they can be regarded as “primary” source material for understanding Jesus.

They are put forth as testimonials, proclamations, and instructional narratives that are centered in one unique person.

This does not PROVE they are adequate for those purposes. So we’re not reasoning in a circle.

But we have common ground to begin a discussion if both the contemporary and (potentially) primary-source nature of the Gospels are mutually recognized.

I am happy for the sake of argument to treat the gospels as coming from the last quarter of the first century. But that is not contemporary with the time of the supposed Jesus. The story only emerges after 70. That’s not contemporary with 30.

In the case of Josephus writing 20 years after the Jewish War we have evidence that the author was contemporary with the events he writes about. We have nothing of the kind re the provenance of the gospels.

You asked for one thing at a time, but if I may venture to the outskirts of another — even if the Gospel of Mark were found to be written as early as 40 c.e. there would still be so many unknowns and questions about the nature of the gospel that we could still not assume it is in any way an historical record. The point about being “contemporary” evidence is not simply “time” but reliability of witness. The point is to locate evidence that can be relied upon as direct or indirect reliable witness to something historical.

In terms of both ancient and modern standards, biographically-oriented material is contemporary if written within a span of a few decades of the subject.

A person who was in his/her seventies or eighties can write, with direct factual references, about events that occurred 40 or 50 years earlier.

So since Christ died about AD 30, a book written about him in AD 70 would be considered contemporary. That is why writings from Josephus are considered contemporary to persons and events in Judea of even 60 years before he wrote.

The contemporary author is one who is theoretically in a position to have information very close to the facts. That is all that is necessary.

All we know is that the first gospel appeared at least 40 years after the events of its narrative. We have no idea who wrote it, what they had personally experienced, where they lived– though we can speculate. Josephus’s writings are contemporary because we know he was alive to witness the events he relates. Just speculating that the author of Mark was in his 70s or 80s is merely speculation. We can speculate he was in his 30s and living in Rome, too.

Josephus is considered contemporary, because of the generally accepted dating of his book. The generally accepted dating of the Gospels, by historians and New Testament scholars, place them all within a maximum of 60 years of Jesus’ death and a minimum of 20 years. The documents are contemporary to the times of Christ — whoever wrote them.

The authors could theoretically have had access to factual information about Jesus. (Whether or not they did must be argued.)

But if you will not even concede the point, there is no ground left between us. Discussion is impossible.

But please dispose of the chatter about someone else’s “woolly thinking” and question-begging, because those labels apply directly to yourself.

If words have any meaning then contemporary means with the same time as something else. Josephus was contemporary with the events.

Just saying that the gospels could have been written by a person in their 70’s doesn’t add anything to what we don’t know about the authorship of the gospels. How many times have I heard historicists accuse mythicists of saying if X could have happened then it probably did? No, that is only speculation and not evidence.

If you want to insist that something written 60 years after an event is contemporary with the event then we simply have to agree to disagree. I don’t know anyone who uses that definition of the word. I do know that theologians very often claim that anything written within a few decades is as good as being written at the same time/contemporary with the event — but that’s only from NT scholars who are using it as a self-serving argument.

But there is something far more fundamental here than the meaning or use of the word “contemporary”. We cannot avoid the fact that the so-called event of 30 c.e. is known only from the narrative of the gospels — the first one of which was written after or around 70.

When you say there was an event in 30 from which we must assess the time the gospels were written, you are only referring to the story in the gospels themselves. We have yet to determine if anything did happen in 30 at all. The only reason we have for thinking something did is the Gospel narrative.

Just because a document that appears around 70 contains a narrative set around 30 we cannot go on to conclude that there really was such an event and the narrative is historical. The narrative cannot be its own self-witness to its truthfulness. We need some form of independent testimony.

As I said, even if we learned that the first gospel was written in 40, it would be meaningless as far as ascertaining that its narrative was in any sense historically reliable.

So let’s say the author of Mark set his story clearly within his own generation, so what? That alone cannot tell us that his story is in any sense “true”.

We need more than a simple claim that a story in a document is set ten, forty or 130 years before the story itself was composed.

You refuse to acknowledge that authors writing within thirty to sixty years after an event may have good information from good sources for what they have written.

Contrary to fact, you refuse to acknowledge that such authors may be regarded, by historians, as contemporary to the events they record. (Had they only written within a few hours, days, or months of the state of affairs they describe, you would grant them the “contemporary” designation. But by that standard, we have no contemporary, second-person historical accounts from antiquity.)

You’re writing pure nonsense.

You have determined in advance that the Gospels are without historical worth, and you will yield no ground whatsoever that even potentially goes against your determination. You cannot admit that there might be a reason that goes against your bias.

You’re not looking for a conversation. Instead you want to send out a barrage of assertions, laced with derision, that will overwhelm all non-compliant readers and send them reeling.

It’s a cheap trick, and I want no part of it.

Please do not respond. This ends my correspondence.

Hi Bobby. You write:

You misunderstand. I do certainly acknowledge that there are many cases where authors writing within thirty to sixty years after an even may have good information from good sources for what they have written. I certainly accept and agree with that. I can think of quite a few examples. Josephus is one of them when he talks about what he was eyewitness to and what we know he learned from his acquaintances and companions.

You write:

I don’t know how I can make it clearer. What I have said is that sources from decades after an event are not contemporary with that event. I have quoted historians who make that very clear. Contemporary means at the same time as something. But we can call Josephus a contemporary source for the Jewish war because his life was indeed contemporary with that war. Ditto for Plato writing about Socrates.

But terms like “contemporary” are really beside the point, aren’t they? Does it really matter what we call things so long as we understand what we mean by them and how to evaluate their value as historical sources?

You write:

I have not said the Gospels are without historical worth a priori. What I have said is that we have no way of knowing that from the start. We need to have some method, some way of finding out if they are of historical worth. We can apply the same methods to the Gospels as we apply to ancient historical documents generally. I have linked to discussions where I have done this. But we can’t begin with an assumption that they are historical records without any form of verification that they really are.

You write:

I was looking forward to a gentlemanly exchange of views. Derision?? Where was I derisive. I certainly think not. Non-compliant readers? I was looking forward to an exchange of understanding. I admit I do ask questions that few of us have ever asked. It took me quite a long time to think through these things and even come to see what are the right questions to ask. I am happy to share a discussion about these things and I am very sorry you consider something so radically different to be “a cheap trick”.

But it is my blog and you are a guest here so I do have a right to respond.

Please leave me out of your ranting.

I’ve asked you to, and now I expect it.

All you would have had to say was, “Yes, a document written within a few decades of specific events may have valuable historical information and is within the gamut of contemporary writing.” Then we would have had common ground on which to begin a discussion.

Instead — from your first comment — you offer an on-going lecture in the form of a barrage of assertions that it would take a book to respond to. (Even this last comment of yours would require a list of clarifications.)

Common ground, followed by one issue at a time, that’s a discussion. Pounding the table and jumping from one topic to another is not.

Now end this thread here and leave me alone. Then you can carry on with other readers who have more capacity than me to tolerate your tactics.

Sigh! Why do so many people who start out offering to engage in reasonable discussion so quickly turn out to nasty personal attacks — and read into the least emotive and straightforward logical argument “rants” or “malice” or “spite” or any expression of “hostility”?

Bobby, my initial comment was not to barrage you — each one was a key facet of my total understanding and was necessary to point out exactly where I am coming from. You were free to engage with any of those points and you did begin with one. But one necessary condition of fruitful exchange is that we set out up front a clear understanding of our terms and avoid confusion of concepts. That is what I thought we were attempting to do at first. I fear you are failing to think clearly and it shows.

But I am saying this for the general reader as a general comment on the way these sorts of discussions always seem to end up — whether with lay people or scholars who come here not really to discuss but to demolish. When they are confronted with questions and views they have never considered before or that are radically at odds with their fundamental assumptions they so often simply spit the dummy. Sigh!

Ehrman: “My point, though, is that the Gospel writers have given us accounts that are contradictory in their details. These contradictions make it impossible for us to think that the stories are completely accurate.”

This is the classic ex-fundamentalist argument for losing faith in the Gospels. Thus, if the Gospels were *not* contradictory in their details, or if we only had one of them, should we then accept them as accurate? This ridiculous argument is made by ex-fundamentalists because they were inculcated in an environment where authority figures told them that the Bible was God’s perfect word. When they read the texts critically as an adult, they discover imperfection, and cognitive dissonance ensues. The stories can no longer be defended as “completely accurate.” The ex-fundamentalist must still defend the integrity of the Bible somehow, so he says that later scribes changed the texts, and we don’t have the originals in either case, the implication being that if we had the autographs *then* there could be no argument: the Gospels are historically accurate and we could go on worshipping the mystic Man-God with a clear conscience and historical certainty.

I think Ehrman’s point is that we have multiple witnesses, but they don’t corroborate one another. What’s worse is they clearly copy from one another, but they change details.

However, I will agree that when we have only one “witness” to a particular event scholars far too often will write, “We have no reason to doubt this.” I think some night I’ll play a drinking game where I take a shot each time I read that line. Probably won’t make it past 10:00 PM.