William Wrede’s The Messianic Secret

Part 3: Introduction

Gospels are stories

In the previous installment, we read through the front matter of Wrede’s The Messianic Secret. This time, we’re going to look at the Introduction, which while technically part of the front matter, is a meaty chapter unto itself.

Quite recently, Neil remarked on this blog:

The most striking thing that hit me in Richard Carrier’s online discussions or articles on Bayes’ theorem was the point that one needs to stop and distinguish between whether we know X happened (e.g. someone saw an empty tomb) or whether what we know is that we have A STORY THAT SAYS X happened.

Apparently, we’re still re-learning the things that Wrede said over a century ago. Indicting the current “defective critical method,” he wrote:

First of all, it is indeed an axiom of historical criticism in general that what we have before us is actually just a later narrator’s conception of Jesus’ life and that this conception is not identical with the thing itself. But the axiom exercises much too little influence. (p. 5, emphasis original)

The story is not the event. The map is not the territory. He then drives the point home even harder, declaring:

I should never for an instant lose sight of my awareness that I have before me descriptions, the authors of which are later Christians, be they ever so early — Christians who could only look at the life of Jesus with the eyes of their own time and who described it on the basis of the belief in the community, with all the viewpoints of the community, and with the needs of the community in mind. For there is no sure means of straightforwardly determining the part played in the accounts by the later view — sometimes a view with a variety of layers. (p. 5)

Wrede is calling attention to the fact that the evangelists were not hermits writing their gospels in a cultural vacuum, transmitting authentic stories verbatim. The gospels represent the beliefs of the communities that created and preserved them, and if we’re going to have any hope of uncovering authentic history from these works (assuming that’s even possible), we’ll need rigorous, rational methods to do it.

Purpose statement

In the fourth paragraph of the Introduction Wrede reveals his purpose, which is to address the following questions (quoting Wrede, but using my formatting):

- What do we know of Jesus’ Life?

- What do we know of the history of the oldest views and representations of Jesus’ life?

- How do we separate what belongs properly to Jesus from what is the material of the primitive community?

Defective critical methods

We’ve already had a preview Wrede’s first failed or “defective” method. Not only do scholars forget that they are dealing with stories transmitted by a community with vested interests, and current needs, but they delude themselves into thinking that once they’ve peeled away impossible and contradictory material, they “are on firm ground in the life of Jesus itself.” But in fact, that task has merely begun.

The second problem Wrede highlights is the tendency to pick out fragments from the gospels that seem to serve our purposes, then hurriedly and without due care, press them into service, divorced from their context and stripped of their original meaning. In other words:

Wrede contends that we should, first of all, understand exactly what the narrator himself had in mind. What was he really trying to convey to his audience? This is the basis of all criticism. Only after fully analyzing and understanding what the writer meant can we proceed.

The third problem Wrede presents is a phenomenon he calls psychological “suppositionitis.” By that he’s referring to way HJ scholars imagine that they can get into the “mind of Jesus.” At first to me this critique seemed to have a rather 19th-century flavor, but I think we can expand the concept to include the political and sociological suppositionitis of the 20th and 21st centuries. I hate to single out any author in particular, since there are many examples, but John Dominic Crossan immediately comes to mind.

He comes as yet unknown to the hamlet of Lower Galilee. He is watched by the cold, hard eyes of peasants living long enough at subsistence level to know exactly where the line is drawn between poverty and destitution. He looks like a beggar, yet his eyes lack the proper cringe, his voice the proper whine, his walk the proper shuffle. (The Historical Jesus, p. xi)

As I said, I don’t mean to pick only on Dom, but his melodramatic “Overture” from The Historical Jesus is practically the quintessential example of Wrede’s malady of suppositionitis. And it isn’t simply a matter of fanciful conjecture that wastes everyone’s time. Not at all, because this rampant psychological speculation has the tendency to become the foundation for subsequent historical research. Wrede doesn’t necessarily dismiss psychological reconstructions out of hand, but let’s be honest — it’s all speculation; it’s all supposition.

He writes:

The psychological treatment of the facts is permissible only when we know that they are indeed facts and even then we must still call a supposition a supposition . . . [O]therwise we will forget that we must at least always be striving for these things and that it is better to have a little real knowledge, whether positive or “negative”, than a great assortment of spurious knowledge. (p. 7, emphasis mine)

Unfortunately, I think today we are awash in “spurious knowledge.” What’s worse, people who stand up and call a supposition a supposition or (more insidious) a presupposition a presupposition are often ridiculed and sometimes slandered.

Regarding our sources

Finally, Wrede turns his attention to our sources. Like most modern scholars, he is convinced that Mark is our first written gospel. He accepts the consensus position that the other synoptics are dependent on Mark, and that John is much later and “must remain out of account as a completely secondary picture.” Hence the burden of historicity weighs heavily on the Gospel of Mark. To put it bluntly:

The reliability or unreliability of Mark’s tradition in this connection is essentially decisive for the reliability or otherwise of the Gospel tradition as a whole.

That’s a sobering assessment. Now Wrede quickly softens the blow by saying that the other three gospels are not “valueless,” but we have to be sober judges here. Mark is undoubtedly the earliest canonical gospel, and if we want to get back to the historical Jesus, it’s the obvious place to start. But as we’ve noted before the reasonably certain antiquity of Mark does not prove the authenticity of Mark. There is no denying that the Gospel of Mark is literary work. It is not a series of news reports from Galilee and Judea.

[T]he Markan narratives are something essentially other than records of Jesus’ life taken down on the spot. This is to be sure a platitude, yet, on the other hand, there is nothing platitudinous about it when one sees that in practice criticism again mostly makes meagre use of this theoretically uncontested thesis.

Even if Mark is making use of eyewitness reports (our absolute best case scenario) it’s abundantly clear that he doesn’t always follow that eyewitness. Mark plainly shows his hand as an author, or at the very least a talented and imaginative redactor. If we admit the obvious — namely, that we’re dealing most likely with what I think Wrede would call a “free interpretation” of the tradition, assembled at least three decades after the fact, then we certainly have our work cut out for us.

So the finished product of Mark’s Gospel is not an exact, faithful recollection of events. It is instead one author’s late conception of events, colored by the current needs of his community, and altered by the process of oral transmission. But that didn’t stop the critics of his day (or the HJ scholars of today) from coming to the most outlandish and unsupportable conclusions.

Thoroughgoing scepticism?

For some readers, the only exposure they’ll ever have to Wrede’s ideas will be from their uninformed professors or from Albert Schweitzer’s chapter in The Quest of the Historical Jesus in which he labeled Wrede’s perspective as “thoroughgoing scepticism.” I have nothing against skepticism, because I think it’s the basis for all modern knowledge. We need to verify everything by diligent analysis of the evidence. And I refuse to apologize for defending the Enlightenment.

On the other hand, the dishonest caricature of skepticism would call it the pathological belief that everything is false until proved true. That is not correct. It’s simply the recognition that all reports are to be given a neutral status until they can be evaluated. Some reports can only be “set aside.” Did Jesus say such and such? It might be plausible, but until we find independent corroboration, how can we justifiably ever say that it’s a “historical fact” that he said it?

I’m not sure Wrede’s “thoroughgoing scepticism” went nearly as far as I would go. However, he rightly understood that we cannot doubt that parts of Mark are clearly ahistorical, and given that knowledge we should be careful about our conclusions. Hence the final words of the Introduction:

To bring a pinch of vigilance and scepticism to [the study of Mark’s Gospel] is not to indulge a prejudice but to follow a clear hint from the Gospel itself.

In our next installment, we’ll begin the book’s Part One: Mark — “Some Preliminaries on the General Picture of the Messianic History of Jesus.”

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

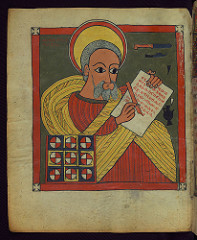

I can only thank Neil Godfrey for so agreeably adding the full reference to the source of his selected illustration. I hope this will become an established feature and will contribute to the image of impeccable scholarship of this site.

As a rule, these marginal illustrations are excellently well chosen. This one is hilarious.

It makes you realize how incredibly easy it was in those days to create a life of Jesus, or of anybody else for that matter. It is still mind-boggling that in our 21st century, so many people can still so comfortably live with the disparate stories of all the Gospels and of Paul, all combined in a huge smörgasbord of religious contentment.

Well, first off, the author was me. Second, I can’t take credit for the full reference to the illustration; that’s done through the magic of Zemanta.

What I found odd about the picture is Mark’s supposed writing position. That’s gotta be uncomfortable.

Sorry about the misattribution. I still hope that full sourcing of illustrations will become a habit.

Well, Mark wants to show what he is writing. I’m sure that the experts at the Museum have deciphered the text.

I looked at the other evangelists’ pictures. Mark’s is the most amusing, because of the face most fully turned to the viewer and his wide-open eyes. He seems very intent. Most amusing. Good choice.

Indeed Mark’s “writing position”, his authoral intent, is the key to understanding all of the writing’s of the NT. I await the next installment with interest.

I’m all agog for the next installment. When do we find out the secret? Does it involve buried treasure?

The Map is not the Territory is discussed on the wiki at Less Wrong, an information rich web site.

The term was coined by Alfred Korzybski, and among the comments in the wiki article cited above, are these:

The books that have come down to us are the Territory, and no amount of wishful thinking will turn them into a map of another territory, i.e. a real Jesus.

Dave wrote, “The books that have come down to us are the Territory . . .”

I’m not sure what you meant by that. If you meant that the texts themselves are the only reality we can grab onto, then I would agree.

My point was to highlight the fact that in general representations of reality (and, specifically, descriptions of the past) are not to be confused with reality. Beyond this point, naturally, is the question of the intent of the author. Did he even intend his map to portray the territory that we imagine?

Given our limited understanding, I think it’s a fallacy to scrape away the implausible parts of Mark and say, “I declare this plausible stuff to be historical bedrock.”

Tim,

To put comments in order: To your reply to ROO I wrote in #2 Comment: Mark’s writing position is the key to understanding (not only Mark) but all of the writings of the NT. Then to your above comment: Mark intended “his map to portray the territory of the Christ of faith”, not “the territory that we imagine”, the man Jesus. I will post more on this later.

Gouchound’s is but one more version of a reading of the writings of the NT (the letters of Paul, the Gospels, as well as the later writings of the NT), from the false assumption that they are our sole NT source of knowledge of the man Jesus (a point applicable as well to Watts, McGrath, and most NT scholars). Again I repeat, this source is written in the context of the Christ of faith, not in the context of the original and originating witness to the man Jesus. It images the mythical Christ figure not the Jesus of history.

Read the above fact of history in the words of Schubert Ogden, one of the finest thinkers of the critical historical New Testament scholars:“ – – the writings of Scripture or of the New Testament can no longer be assumed to constitute a proper canon. This objection rests on the claim that, given our present historical methods and knowledge, none of the writings of Scripture as such can be held to satisfy the early church’s own criteria of canonicity. We now know not only that none of the Old Testament writings is apostolic witness to Jesus in the sense in which the early church assumed them to be, but also that none of the writings of the New Testament is apostolic witness to Jesus as the early church itself understood apostolicity. The sufficient evidence of this point in the case of the New Testament is that all of them have now been shown to depend on sources earlier than themselves, and hence not the original and originating witness that the early church mistook them to be in judging them to be apostolic.” (Faith and Freedom).

“Mark’s ‘writing position’, his authoral intent, is the key to understanding all of the writing’s of the NT.”–

I have two questions here.

(1) In discussion great poetry, would not be a question of the “authoral intent” be illegimate (with all we know about the sub-conscious operative in creation of poetic symbols)?

(2) If this is true of poetic, why could not it be so of divine inspiration?