In my previous post I cited Leopold von Ranke’s famous explanation for history being an art. (I turned to von Ranke because a biblical scholar quoted von Ranke to me without knowing the source of his quotation, nor its meaning.) Now von Ranke’s philosophy of history and views on the nature of historical facts have been superseded throughout the twentieth century. But he gave expression to the meaning of history as an “art” (explained in my previous post), and to the importance of reliance first and foremost on empirically verifiable primary sources (sources physically located in the time and place of the subject of historical inquiry), and these concepts have stood the test of time for most historians.

In my previous post I cited Leopold von Ranke’s famous explanation for history being an art. (I turned to von Ranke because a biblical scholar quoted von Ranke to me without knowing the source of his quotation, nor its meaning.) Now von Ranke’s philosophy of history and views on the nature of historical facts have been superseded throughout the twentieth century. But he gave expression to the meaning of history as an “art” (explained in my previous post), and to the importance of reliance first and foremost on empirically verifiable primary sources (sources physically located in the time and place of the subject of historical inquiry), and these concepts have stood the test of time for most historians.

But in my citation of von Ranke’s explanation of the nature of history as an art, one also reads that this same grandfather of modern history said history is a “science”.

If one reads that citation of von Ranke’s in the previous post, and the discussion of other milestone figures in the development of historiography as I presented them in my earlier post on how historical Jesus studies differs from normative nonbiblical historical inquiry, one will see that history has been compared to a “science” for the following reason.

Science begins with empirical data

Science deals with facts. And when scientists speak of “evidence”, they speak of verifiable, empirical facts that suggest support for a theory.

This is the same way criminologists work. They are in effect practitioners of applied science. When a detective speaks of a “fact” or “evidence”, he or she is speaking of something empirically verifiable, like a fingerprint, a body, a broken lock, a blood-stained knife.

In this sense, history is also sometimes called a “science” (or at least it used to be called this more than it is nowadays, if I am not too out of touch with current developments), because it deals with empirical facts, data, such as primary source documents like diaries, government documents, church registries, telegrams, newspaper articles, gravestone inscriptions, radiocarbon test results, coins, pottery, and so forth.

It is such primary sources that verify for us the facts that Washington was the first President of the USA, that Bismarck instigated the Franco-Prussian War, that untold numbers of communists, Jews, Romany, Poles, homosexuals, physically handicapped and others were slaughtered in central Europe in the 1940s, that aboriginal Australian were only allowed to vote for the first time as late as the 1960s.

History is not really a science in the sense that its hypotheses can be experimentally tested. No-one can repeat the scenarios. There is still a good measure of “art” attached to the way historians piece their interpretations of the primary sources together to tell a particular narrative.

Now contrast the above with historical Jesus studies.

Historical Jesus scholars have no primary sources in the sense described above. That is, there is no evidence for Jesus today that physically belongs to the time Jesus supposedly lived. This was understood long ago but that understanding appears to have been lost today:

Moreover, in the case of Jesus, the theoretical reservations are even greater because all the reports about him go back to the one source of tradition, early Christianity itself, and there are no data available in Jewish or Gentile secular history which could be used as controls. Thus the degree of certainty cannot even be raised so high as positive probability. (Schweitzer, Quest, p.402)

What biblical historians work with is literary material that is undeniably full of myth and theology. They bring to this literature, bequeathed to them via the politics of fourth-century religious and political struggles, the assumption (faith) that it was declared back then to contain: an account of a true event in history. While the mythical and blatantly tendentious elements of the narratives are not generally accepted as historical today by most scholars, there remains the belief that the narratives nonetheless derived from oral traditions that were given birth by real history. There are many problems with this assumption, and “the easter experience” in particular is still widely relegated to “the inexplicable”.

So what ‘historians’ do is try to find some ‘facts’ about Jesus behind all this literature of myth and theology. Contrast this with the above explanation of what other historians do. They begin with empirical facts and seek to explain them. HJ scholars begin with no facts, only a myriad of late secondary assertions, and seek to discover some ‘facts’.

“Real” historians begin with, work with, facts that all historians and public readers can empirically verify are facts. There is of course the issue of probability. But I am talking here about empirically verifiable evidence or sources such as telegrams and inscriptions. I am also talking about evidence from secondary sources that can be independently and multiply verified and whose probability is also enhanced through such external corroboration and literary analysis.

In contrast to how “real” historians ideally work, HJ “historians” begin with a search for some “facts”. They use criteria (e.g. of embarrassment, dissimilarity, etc). Similar criteria are sometimes used by “real” historians to analyze and interpret facts. But HJ “historians” use criteria to try to find something in the gospels that they can all agree are “facts”. Not all historians do agree. So there is no single body of empirical factual evidence for all historians to discuss and analyze. There are only competing claims about what is “fact” and what is not. Result: some think Jesus was a revolutionary, some a magician, others a rabbi.

There is no such identity crisis in any figure I know of from nonbiblical history. And the reason is simple. Nonbiblical historians work with empirical facts from the start. They tailor their questions and inquiries to what such evidence allows them to investigate. No such evidence, no history.

Imagine a detective beginning with a hearsay account of a murder, and without knowing who made this assertion, and without any empirical evidence that there was a murdered victim, or that the said person had even existed, yet proceeded to seriously investigate the hearsay claims, apply criteria of embarrassment and dissimilarity to that unsourced assertion, and on that basis bring charges against someone in court!

We cannot change the rules of the game, but HJ “historians” do change them

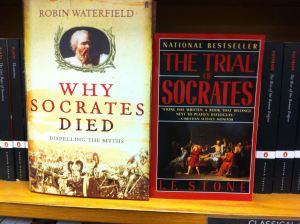

Today I was scanning the history shelves in Singapore’s Orchard Road Borders Bookstore and took particular attention to see what was new in the ancient history section. It is remarkable how few historical topics of a very narrow focus there are in the ancient history section. Most deal with broad sweeps of “the fall of the Roman Empire”, “the rise of Athenian democracy”, the social life of . . . . etc. The few that are narrowly focused are mostly about figures like Hadrian and Julius Caesar for which historians have an unusual abundance of primary source material and/or secondary sources that can be truly independently corroborated. The secondary sources are not only in such abundance and capable of external corroboration, they also are such that their literary genres and styles and contents can be analyzed in ways that can enable historians to make widely-accepted views as to the historical reliability of their respective contents, the specific biases in each, and the extent of tentativeness that most scholars will agree can be attributed to certain kinds of information in them.

Once one comes to the modern history shelves, there is a distinct change in the nature of the topics investigated by historians. The titles are very specific, often addressing a single individual (not even major leaders), one narrow period of a single political party, a few short years in the life of one minority ethnic group in one part of one city. On larger topics, such as a world war, there are endless volumes dealing exclusively with just one aspect of it from a wide constellation of viewpoints.

One exception on the bookshelf

There was one exception to this in the ancient history section. I did find two books on “the historical Socrates” – pictured above. The authors (or one of them, I don’t recall which) justified their books by pointing to the independently corroborated contemporary evidence for Socrates: Plato’s assertion that Socrates was a friend of the playwright Aristophanes is supported by references to Socrates in Aristophanes’ plays. None of this is primary evidence in von Ranke’s usage of the term. But since the evidence involves multiple and truly independent attestation, it does give some weight to the probability of the historicity of Socrates.

Among a few scholars there has been some question even about the historicity of Socrates.

So where does that leave Jesus as a viable topic of history as both “an art and a science” if we don’t even have multiple and truly independent attestations of him?

Moreover, in the case of Jesus, the theoretical reservations are even greater because all the reports about him go back to the one source of tradition, early Christianity itself, and there are no data available in Jewish or Gentile secular history which could be used as controls. Thus the degree of certainty cannot even be raised so high as positive probability. (Schweitzer, Quest, p.402)

Schweitzer is speaking theoretically. But scholarly history demands a theoretical foundation. Schweitzer went on to warn that Christianity must accordingly build its faith in a metaphysic that does not rely on a “historical Jesus” or any event in history at all. But few Christians seem to have liked this suggestion.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

In one respect, history is at a serious disadvantage with respect to the hard sciences. When a chemist or physicist makes a hypothesis, we can perform repeated experiments to prove whether the hypothesis is false (or falsifiable, for that matter). Historical events occur once and are lost to the past. We have no direct access to the past, only the recollections of others. So even in the best of cases, we can only establish high probability. You would think that being stuck with late, contradictory, anonymous and pseudonymous sources would make Bible scholars more cautious. You’d be wrong.

Biblical scholarship is the only sub-field of history in which I’ve heard actual scholars use the term “innocence of the text” and accuse others of being “too skeptical.” It’s the only sub-field in which scholars feel obliged to publicly state that they don’t discount supernatural events, as if not believing in miracles and magic would be grounds for dismissal. (I know of no Homeric scholars who feel compelled to say they’re not sure whether Athena appeared on the field of battle at Troy.)

NT scholars are an even rarer breed. They take literary relationships and turn them into historical relationships. They transform plausible scenarios into hard facts. They create source documents out of thin air. They imagine an oral tradition that goes on for 40 years, but still contains factual information. They ostracize dissenters and then ask why they don’t get published in respected journals. Ask yourself, why did Earl Doherty have to self-publish a monumental work like Jesus: Neither God nor Man? Why did Thomas L. Thompson have to leave the U.S. and find a teaching position in Copenhagen? Why is it that Robert M. Price, a man with two earned PhDs, can’t find a position in any American university?