Even ancient scribes had problems with some of the laws that were decreed from the mouth of the Almighty himself. Take the commandment against idolatry thundered from Mount Sinai:

Even ancient scribes had problems with some of the laws that were decreed from the mouth of the Almighty himself. Take the commandment against idolatry thundered from Mount Sinai:

You are not to make yourself a carved-image

or any figure

that is in the heavens above, that is on the earth beneath, that is in the waters beneath the earth;

you are not to bow down to them,

you are not to serve them,

for I, YHWH your God,

am a zealous God,

calling-to-account the iniquity of the fathers upon the sons, to the third and fourth generation

of those that hate me….

(Exodus 20:4-5, Everett Fox trans)

Poor unlucky great-great-great grandchildren.

Fortunately for those innocents scribes or priests knew how to subvert God’s command.

But since they are playing with God’s own words they need to be clever enough to avoid detection.

The first rule they followed was to remain anonymous. Mustn’t make it easy for God to identify the culprit.

Just as there is not a single law in the Bible that Israelite authors do not attribute to God or his prophetic intermediary, Moses, so is the converse also true. In the entire Hebrew Bible, not a single text, legal or otherwise, is definitively attributed to the actual scribe responsible for its composition. Except for the prophets, biblical authors never speak explicitly in their own voice. Instead, they employ pseudonyms or write anonymously. Proverbs, for example, is attributed to Solomon by means of its editorial superscription (Prov. 1:1), while Ecclesiastes is similarly ascribed to “the son of David, king in Jerusalem” (Qoh. 1:1). Neither of these attributions withstands critical examination.28 Such attributions seem rather to function to lend greater authority or prestige to a literary composition by associating it with a venerable figure from the past . . . (Levinson, Bernard M. (2003). “You Must Not Add Anything to What I Command You: Paradoxes of Canon and Authorship in Ancient Israel”, Numen, 50.1, p. 15)

It was a different matter if laws were merely “man-made”. What one mortal decreed another mortal could strike out and replace. So it was, for example, with ancient Hittite laws as we see from the following case:

If anyone blinds a free person or knocks his teeth out, formerly they would pay 40 sheqels of silver, but now one pays 20 sheqels of silver. . . (Hittite Laws #7, cited in Levinson, 2003)

Inflation or the greater need to allow for knocking out the eyes and teeth of undesirables required a change in the law and it was effected as simply as the above example shows.

But one can’t be so blunt if the laws have been divinely revealed from heaven.

Before showing how the literate class managed to nullify God’s eternal words let’s see where the idea of punishing future generations originated. It did not begin with God, but God picked it up from his reading of Near Eastern treaties.

These ancient Near Eastern treaties were understood as being made in perpetuity. They were therefore binding not only upon those immediately signatory to them but also upon succeeding generations. Consequently, the punishment for non-compliance stipulated the execution both of those actually party to the treaty and of their progeny. That principle of distributive justice underlies Yahweh’s threat that he will visit his rage upon the third and fourth generation of those guilty of breaking the covenant.51 The extension of retribution across three generations strikingly resembles a similar formulation found in a group of treaties made between the Neo-Assyrian ruler Esarhaddon and his eastern vassals in 672 B.C.E. In order to ensure their allegiance to Assurbanipal, his heir designate, Esarhaddon required that they take an oath stipulating both loyalty and accountability across three generations:

“As long as we, our sons [and] our grandsons live, Assurbanipal, the great crown prince designate, shall be our king and our lord. If we place any other king or prince over us, our sons, or our grandsons, may all the gods mentioned by name [in this treaty] hold us, our seed, and our seed’s seed to account.”52

(Levinson, 2003. p. 27)

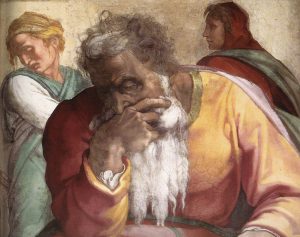

How “Jeremiah” opposed the injustice of God

A clause like that might be fine with power and ego obsessed psychopathic kings and deities but it did not go down well with the innocent victims. Even a biblical author associated by some with name of Jeremiah squeaked out the pain of its injustice:

Our fathers sinned and are no more;

But as for us — the punishment for their iniquities we must bear! (Lam. 5:7)

“Jeremiah” did not know how to neutralize God’s way for his suffering compatriots in the here and now but did think that one day in the future God would make everything right and just. God would make a new covenant with new and fairer laws in the future:

27 “Behold, the days come,” saith the Lord, “that I will sow the house of Israel and the house of Judah with the seed of man and with the seed of beast.

28 And it shall come to pass, that as I have watched over them to pluck up and to break down, and to throw down and to destroy and to afflict, so will I watch over them to build and to plant,” saith the Lord.

29 “In those days they shall say no more: “‘The fathers have eaten a sour grape, and the children’s teeth are set on edge.’

30 But every one shall die for his own iniquity: every man that eateth the sour grape, his teeth shall be set on edge.

31 “Behold, the days come,” saith the Lord, “that I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah—

32 not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers in the day that I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt, My covenant which they broke, although I was a husband unto them,” saith the Lord.

33 “But this shall be the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel: After those days,” saith the Lord, “I will put My law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts, and will be their God, and they shall be My people.

That’s one way of changing the law. Predict that God will replace his old covenant with a new one in the future.

The Subtle Subversion by the Deuteronomist

But the author of Deuteronomy, like the serpent, is yet more subtle, as sly with words as a politician or a lawyer.

First the author repeats the gist of the Exodus command as the words of God

for I, YHWH your God, am a jealous God,

calling-to-account the iniquity of the fathers upon the sons to the third and fourth generation of those that hate me,

but showing loyalty to thousands

of those that love me, of those that keep my commandments.(Deut. 5:9, Everett Fox)

True. Yes, that’s what God essentially said on Sinai according to the Book of Exodus. (You’ll see the relevance of the highlighting in what follows.)

Shortly afterwards our author repeats the key words (bolded above) but this time he paraphrases them through the mouth of Moses. It sounds like he is repeating the law with nothing more than a new emphasis . . . .

Know

that YHWH your God, he is God,

the trustworthy God,

keeping the covenant of loyalty with those who love him and with those who keep his commandments,

to the thousandth (generation),

and paying back those who hate him to his face, by causing them to perish —

he does not delay punishment to those who hate him to his face; he pays them back!(Deut 7:9-10, Everett Fox)

Listen, oh faithful, to the loyal servant Moses repeating God’s words, using some of God’s exact key words (bolded), but within a new paraphrase.

We know Deuteronomy 7 is a deliberate rephrasing of Deuteronomy 5 because of a technique called Seidel’s Law. M. Seidel discovered it so it bears his name. It’s the literary technique of inverting a citation to mark its reuse:

A those that hate me

B thousands

C those that love . . . keep my commandments

C1 those who love . . . keep his commandments

B1 thousandth

A1 those who hate him

Notice the expression “to his face” (twice) in Deuteronomy 7. That’s an idiom meaning “in his lifetime”.

Oh the depths of subtlety! Our author has with shiny haloed face put in the mouth of God’s most trusted servant, Moses, the very words of God in a paraphrase of God’s command, but omitting some small detail. . . . the reference to the third and fourth generation. God is now saying through Moses — and he is merely elaborating on his earlier words, so it seems — that the sinner shall be punished; that those who hate him will be punished, that those (the thousands) who love him and keep his commandments will be blessed. Certainly there is no contradiction, God forbid! But there is subversion of the original command.

The author has repeated key “canonical” words so readers can be sure to know which commandment is being addressed, but with each repeat there is a new gloss.

The authors of Deuteronomy employ two techniques to present their reformulation covertly.

The first is [“canonical”] citation and reformulation, as what purports to be mere paraphrase in fact constitutes a radical subversion of the textual authority of the Decalogue. The new doctrine of individual retribution cites the very doctrine that it replaces, yet does so “atomistically,” selectively redeploying individual words as markers of tradition while breaking down their original semantic reference.70 Reduced to a cluster of individual lemmas and then reassembled in a new context, the older doctrine becomes infused with new content. Citation here seems to function less as an acknowledgement of the authority of a source than as a means to transform that source: to “re-inscribe” that source in a new context that, in effect, restricts and contracts its original authority.71

The second device is pseudepigraphy, the attribution of a text to a prestigious speaker from the past.72 The authors of Deuteronomy do not write directly in their own voice. Instead, they harness the voice of Moses in order, literally and metaphorically, to “authorize” their reformulation of the Decalogue. The risk of discontinuity with tradition is thus paradoxically avoided by attributing the revision of the Decalogue doctrine to the same Mosaic speaker credited with propounding it in the first place.

(Levinson, 2003. pp. 42f)

Ezekiel’s Side-Stepping Subterfuge

Ezekiel’s technique was to shift the goalposts. He first set up something a straw man. Obviously one cannot hold up the words of God as the target to be fired at, so Ezekiel constructed a folk proverb that contained echoes of the law of God — but hey, it was a folk proverb, hence vulnerable to criticism. Read Ezekiel 18:

1 The word of the Lord came unto me again, saying,

2 “What mean ye, that ye use this proverb concerning the land of Israel, saying: ‘The fathers have eaten sour grapes, and the children’s teeth are set on edge’?

3 As I live, saith the Lord God, ye shall not have occasion any more to use this proverb in Israel.

4 Behold, all souls are Mine. As the soul of the father, so also the soul of the son is Mine: the soul that sinneth, it shall die.

Jeremiah could not bring himself to change God’s law for the here and now; he could only put off that day into the distant future. Ezekiel is more bold, but not so bold to attack God’s words directly. He first takes the moral of God’s law and rewrites it into a fallible human folktale.

Ezekiel therefore uses the proverb as a strategic foil for the far more theologically problematic act of effectively annulling a divine law. The prophet in effect “de-voices” the doctrine’s original attribution to God and then “re-voices” it as folk wisdom. By this means the oracle obscures its subversion of the divine instruction found in the Decalogue. While it is a simple matter to repudiate a folk saying, it cannot but raise serious theological problems to reject the Decalogue’s concept of transgenerational punishment as morally repugnant.

(Levenson, 2003. p. 33)

Not that Ezekiel was striking out blindly here. He at least had the civil and criminal code in the Pentateuch to lean on. In a list of laws concerning marriage and inheritance, kidnapping, loans, wages, limits on corporal punishment, etc, we read the following:

Fathers re not to be put-to-death for sons,

sons are not to be put-to-death for fathers:

every-man for his own sin (alone) is to be put-to-death!

Deuteronomy 24:16

Recalling Seidel’s Law notice how Ezekiel has taken the above principle of secular justice and applied it to sin against God’s direct commands:

The person who sins, (only) he shall die:

a son shall not bear the iniquity of the father,

nor shall the father bear the iniquity of the son.

Ezekiel 18:20

The formulation of the new conception of divine justice echoes the existing rule requiring individual liability in matters of civil and criminal law. In the latter sphere, biblical law prohibits vicarious punishment and specifies that only the perpetrator should be held accountable. . . .

The formula for individual liability in civil and criminal law thus almost certainly served as a legal and literary precedent for the prophet.60 It enabled him to bring theological justice into conformity with secular justice by means of analogical legal reasoning.

(Levenson, 2003. pp. 33f)

Once on a roll Ezekiel stripped the folk proverb of all shred of validity by waxing eloquent on how neither sin nor righteousness, neither reward nor punishment, could ever justifiably be transferred across generations: 18:10-20.

–o0o–

And so it goes. What one generation found repugnant another generation could, with a bit of rhetorical training and imaginative use of words and ideas, overturn — subtly — while still appearing never for a moment to challenge the very word of God as pronounced on Mount Sinai.

There is a more fundamental message here that goes beyond mere scribal ingenuity. It has to do with the way our ancient Judean authors understood the authority (or otherwise) of sacred writings. Never would they admit to “adding to and taking from” the revealed word of God, God forbid!, but that did not prevent them from finding ways to introduce new revelation that did indeed have the effect of subverting the old.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Still, once Yahweh had smote the 1st generation to death and the second generation to death where would the third and fourth generations even come from?

Its’ the whole ‘killing all the Egyptian livestock’ three times over routine as a policy.

Regarding your last paragraph, I would agree that authors of the hebrew bible would not “add or take away from’ sacred texts that went before. But they weren’t necessarily subverting those texts either.

If you would cite the verse following Exodus 20:4-5, I think you can see that the interpretation that Deut 7:9-10 gives is already enclosed in Exodus 20:

I think a permissible reading of Exodus 20:5 says that God would punish those who hate (= reject) God, and include up to the fourth generation – if these generations also hate God. This reading is supported by Exodus 20:6, which says that God will show kindness to the thousandth generation (= forever) of those who love Him (and obey His commands). I would say this only makes sense if here – also – each generation is judged individually; if not, descendants of a God fearing generation would forever be shown kindness, even if subsequent generations would reject God.

In this light, Deut 7:9-10 is not a subversion, but a clarification of Exodus 20:5-6.

However, things are seldom simple in the Hebrew bible. For example, Exodus 34:7 gives a similar command of punishment, extending up to the fourth generations of sinners, but without the ‘love and hate’ qualifiers. On the other hand, God includes here that He forgives sin, so perhaps this phrase means to indicate that God ‘reserves the right’ to punish later generations (as a deterrent), but does not intend to apply this right?

On a higher level, the real issue appears to be the problem of suffering in the world. The deuronomistic histories seem to attribute suffering of whole nations to wrongdoings of their kings. This explanation became problematic, and other origins of suffering were investigated (e.g. a test by God, as in the book of Job). In the later books (e.g . Daniel) suffering is attibuted to ‘dark forces’ that will – soon – be defeated by God.

So there is a long evolution of the thoughts around the nature of suffering in the Hebrew bible, and the quoted paragraphs appear to just scratch the surface.

Ah, the revisers and subverters on reading your post would be proud of their job being so well done! 🙂

It sounds the very example of what I understand to be ‘midrash’. Is that a correct understanding?

Hey I just wanted to commend Neil for this fantastic post! To me this is one of the most interesting and thought-provoking posts I’ve found here. That inside-out rhetorically technique for subverting a bit of text, under the guise of clarification, is fascinating.

Thanks for the thanks. Looking forward to doing more when other matters involved with resettlement in a new place of abode eventually allow me the time.