“Jesus and Dionysus in The Acts of the Apostles and early Christianity” by classicist John Moles was published in Hermathena No. 180 (Summer 2006), pp. 65-104. In the two years prior to its publication the same work had been delivered orally by John Moles at Newcastle, Durham, Dublin, Tallahassee, Princeton, Columbia, Charlottesville and Yale.

“Jesus and Dionysus in The Acts of the Apostles and early Christianity” by classicist John Moles was published in Hermathena No. 180 (Summer 2006), pp. 65-104. In the two years prior to its publication the same work had been delivered orally by John Moles at Newcastle, Durham, Dublin, Tallahassee, Princeton, Columbia, Charlottesville and Yale.

The names Moles thanks for assistance with this work are many: Loveday Alexander, John Barclay, Stephen Barton, Kai Brodersen, John Dillon, Jimmy Dunn, Sean Freyne, John Garthwaite, Albert Henrichs, Liz Irwin, Chris Kraus, Manfred Lang, Brian McGing, John Marincola, Damien Nelis, Susanna Phillippo, Richard Seaford, Rowland Smith, Tony Spawforth, Mike Tueller and Tony Woodman.

John Moles begins his article with two questions. The first of these is a dual one:

Is Acts influenced by Dionysiac myth or ritual and does it quote the play Bacchae?

Old questions, yes, but they are still being raised in the literature, as Moles indicates with the following list:

E.g. Nestle (1900); Smend (1925); Fiebig (1926); Rudberg (1926); Weinreich (1929) ; Windisch (1932); Voegeli (1953); Dibelius (1956) 190; Hackett (1956); Funke (1967); Conzelmann (1972) 49; Colaclides (1973); Pervo (1987) 21-2; Tueller (1992); Brenk (1994); Rapske (1994) 412-19; Seaford (1996) 53; (1997); (2006) ch. 9; Fitzmyer (1998) 341; Dormeyer-Galindo (2003) 49 ff.; 95; 365; Hintermaier (2003); Lang (2003); (2004); Weaver (2004); Dormeyer (2005).

The second question is the one that is the main point of the article and the one given the most space in answering:

If the answers to the above are affirmative, what are the consequences?

I have it on authority that John Moles is not a mythicist so those who read this blog with a jaundiced eye can look elsewhere for material that serves their agenda.

Broad thematic parallels between Acts and Bacchae

John Moles lists the following:

- the disruptive impact of the ‘new’ god

- judicial proceedings against the ‘new’ god and his followers

- ‘bondage’ of the ‘new’ god or his followers

- imprisonments of the ‘new’ god’s followers

- their miraculous escapes from prison

- divine epiphanies

- warning that persecution of the ‘new’ god or his followers is ‘fighting against god’

- a direct warning by the unrecognized ‘new’ god to his persecutor

- ‘fighting against god’ by the ‘new’ god’s persecutor

- ‘mockery’ of the ‘new’ god or his followers

- general human-divine conflict

- kingly persecutors

- a kingly persecutor who arrogates divinity to himself

- divine destruction of impious kingly persecutor

- rejection of the ‘new’ god by his own, whom he severely punishes

- the destruction of the palace/temple

- adherence of women to the ‘new’ religion

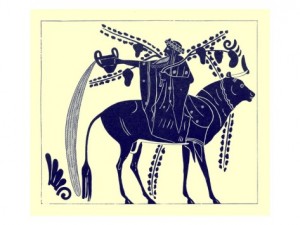

- Dionysiac ‘bullishness’

Though some of these parallels need justification, as Moles points out, it is clear that the two texts “share numerous important themes”. The possibility that the Bacchae influenced Acts is thus not implausible.

Detailed thematic parallels between Acts and Bacchae

Moles lists three “crucial cases”. They all relate to the one section of the Bacchae — the epiphany of Dionysus and his prison escape — so I quote that here. Note the word “relate”: John Moles does not argue that the passage itself directly inspired the various accounts in Acts. Understand that in the play Dionysus was not recognized as Dionysus by King Pentheus. Pentheus believed he had imprisoned a mortal troublemaker who worshiped Dionysus. The translation is by George Theodoridis:

From within the palace we hear the crashing and smashing of a building and the voice of Dionysos calling his followers.

Dionysos:

Io! Io! Hear my voice! Hear my voice, my followers! Bacchants! Bacchants!Chorus:

Who’s there? Who’s there? I heard the voice of Dionysos. Where did he call me from?

Dionysos:

Io! Io! I call again! It is I, the son of Zeus and Semele.Chorus:

Io! Io! My Lord! My Lord! Come to us, Dionysos, my Lord!Dionysos:

Move Earth, move! Shake, our beloved Earth!More collapsing of the building

Chorus:

Quick! Pentheus’ palace is being turned into ruins.

Dionysos is in those ruins! Pray for him!

Ahhhh! I’m praying for Dionysos!

Look, the stone pillars and those logs! See how they rolled out of their position! Dionysos is calling out from in there somewhere, under the palace’s roof.Dionysos:

Lightning strike! Light up your burning torches! Put Pentheus’ chambers to the torch!The light on Semele’s tomb shoots up for a second.

Chorus:

Ah! Did you see the flame on Semele’s holy tomb? Once the flame of lightning extinguished it with Zeus’ thunder.

Throw your shaken bodies to the ground, maenads! Throw them!

The chorus falls around the tomb in supplication.

After a short pause:

The palace door opens and Dionysos enters, barely touched by the disaster inside.Dionysos:

My dear Lydians, are you so frightened that you fell prostrate to the ground? Looks like you realised that Dionysos has destroyed Pentheus’ house. Come on, get up now and show some courage. Shed away your body’s terror.Chorus:

How bright is the light of our joy!

How happy we are to see you!

We despair no longer!Chorus:

We are no longer unprotected!Dionysos:

Were you saddened when they took me and threw me in Pentheus’ dark jails, my dears?Chorus:

How could we not be sad? Who would be our protector if you fell into some terrible misfortune? But how did you manage to free yourself from the grips of that irreverent man?Dionysos:

Easily. I freed myself with ease.Chorus:

But didn’t he have your hands tied up with thick knotted ropes?Dionysos:

And that’s exactly where I showed him how foolish he is. His mind was full of hope instead of reality and so, in his delusion, he thought that he had tied me up but, the fool, he had neither touched me nor hurt me in the slightest.

He took me to the stall of a bull and instead of tying the ropes around my hands he tied them around the bull’s knees and hooves, all the while fuming with rage, his body covered in sweat and biting at his lips. I watched him from nearby in utter comfort.

It was then that Dionysos came and lit the flame on my mother’s tomb. As soon as he saw that he thought that the palace was burning and so he was jumping all around the place, shouting for someone to bring Aheloos in there. All the slaves got down to work but – all in vain!

I left then and he, too, gave up on trying to save the palace, found his black sword and rushed out into all the rooms.

But I think that Dionysos created an apparition in the court and Pentheus charged at it, fighting it as if he was fighting me. More than that, Dionysos, seeing my awful fetters, gave Pentheus something else to think about: He shook the palace from the foundations up, smashed everything! Stupid boy, he was so exhausted now, he dropped his sword and gave up. Irrational man! A mortal trying to fight it out with a god! So, I quietly got out of the palace, forgot about the fool and, here I am, among you!

Sounds of heavy footsteps from within.

Ah! I think I can hear the heavy footsteps of army boots. I’m sure he is coming out here. I wonder what he’ll say about all this. This will be an easy job for me. Let him be as furious as he wants. I shall meet him calmly because that is how wise people work, calmly.

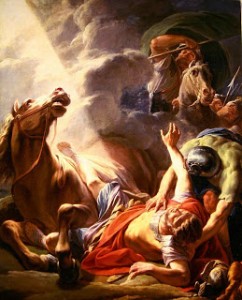

A. The accounts of Paul’s conversion are more well known so I won’t quote them here. They can be read at Acts 9:3-9. Acts 22:6-11 and Acts 26:12-18.

A. The accounts of Paul’s conversion are more well known so I won’t quote them here. They can be read at Acts 9:3-9. Acts 22:6-11 and Acts 26:12-18.

The points in common:

- Light and lightning

- People falling to the ground

- Invisible divine voice

- Divine voice addressing people by name

- People asking a question

- The god identifying himself

- The divine command to get up off the ground and stand up

- Seeing the god

- Response is submission or defiance (conversion or non-conversion)

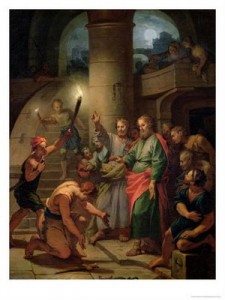

B. Herod Agrippa’s persecution, attempt to kill Peter and Peter’s escape from prison. See Acts 12:1-10.

B. Herod Agrippa’s persecution, attempt to kill Peter and Peter’s escape from prison. See Acts 12:1-10.

In common:

- A ruthlessly persecuting king

- Followers of the god are imprisoned

- Stressing the strength of the imprisonment

- Stressing the suddenness of the supernatural intervention

- Divine light

- Divine instruction to stand up

- Confusion between vision and reality

- Miraculous opening of the prison gate

- Both narratives subsequently report the death of the persecuting king

C. The miraculous deliverance of Paul and Silas from prison and the conversion of the jailor. See Acts 16:23-30

C. The miraculous deliverance of Paul and Silas from prison and the conversion of the jailor. See Acts 16:23-30

In common:

- Prayer by the god’s followers

- Suddenness of the epiphany

- Earthquake

- Collapse of building

- Miraculous release of prisoner’s bonds and of doors

- Surprise and confusion of the jailor

- Darkness to light

- Jailor draws his sword

- Jailor rushes to the interior

- Jailor falls to the ground

- Conversion (or reaffirmation of conversion) by god’s followers or non-conversion

- Prisoner claims he has not run away

- Focus on the jailer’s final religious response: since the prisoner has not been lost, will he accept the divine warning or reject it?

John Moles is a classicist. He acknowledges that New Testament scholars (Wright, 2003; Barrett, 2004, Haacker, 2003) prefer to find parallels with Jewish literature:

2 Maccabees 3 (Online) A divine epiphany prevents the Syrian king’s agent, Heliodorus, from plundering the temple.

In common:

- Resplendence

- Falling to the ground

- Darkness

- Person in need of assistance from attendants

- Conversion / religious transformation

Joseph and Aseneth 14:2-8 (Online) Aseneth is converted after a heavenly vision.

In common:

- Heavenly light

- Falling to the ground

- Divine figure (though not the god) addressing a human by name

- The mortal asking for the identity of the divine figure

- Divine figure identifying himself

- Divine figure telling the mortal to stand up

- Conversion

- Divine instructions

Ezekiel 1.28-2:1 (Online)

In common:

- Heavenly light

- Falling to the ground

- God telling the human to stand up

- God giving the human instructions

Daniel 10:5-11 (Online)

In common:

- Lightning mentioned as a comparison

- Human falling to the ground

- Angel addressing the human by name

- Angel telling the human to stand up

- Angel giving instructions

Compare also the “call of the prophet stories” Isaiah 6:1-13 and Jeremiah 1:4-10.

1 Samuel 26:17-18 (Online) recalls one element in the midst of a complex sequence:

Saul recognized David’s voice and asked, “David, is that you, my son?” “Yes, Your Majesty,” David answered. And he added, “Why, sir, are you still pursuing me, your servant?

John Moles’ evaluation:

- 1 Samuel 26:17-18 matches only one element

- “Call of the Prophet” narratives produce only very general parallels

- The most substantial Jewish parallels are 2 Maccabees 3 and Joseph and Aseneth 14:2-8. Both of these, moreover, are probably influenced by non-Jewish literature and themes: 2 Maccabees itself contains Dionysiac elements and Joseph and Aseneth is suspected by some scholars of being Christian influenced.

- 2 Maccabees 3 “contains some very discrepant elements”

- Bacchae contains more and better parallels than both (e.g. the divine figure is the god himself and the light is lightning)

- “Further, the Jewish material scarcely illuminates the narratives of Peter and of Paul and Silas, in relation to both of which, especially the latter, the Bacchae parallel is extremely strong. Moreover, all three narratives are thematically interrelated, and the parallels between Peter’s and Paul’s releases and the release of Dionysus in Bacchae were already noted by the Christian apologist Origen in ca. 249 CE (Contra Celsum 2.34).”

I conclude that, while there is some Jewish input into these narratives, the Bacchae parallel is far stronger. But what does it mean? Luke demonstrably uses Bacchae elsewhere in Acts, so Bacchae 576-641 may some provided some inspiration here as well, particularly in relation to 26.12-18 . . . . But it seems unlikely that the three narratives were inspired by a single Euripidean passage or by any single intermediate source, now lost. Rather, there is a more general appeal to the patterns of initiation into Dionysiac cult that underlie Bacchae 576-64110 and to prose works – such as the novel – that incorporate such Dionysiac patterns into their narratives. (p. 69, my emphasis)

Quite specific verbal parallels convince Moles that the author of Acts did indeed use Bacchae in addition to drawing upon more general Dionysiac material.

Verbal parallels between Acts and Bacchae

|

Acts |

Bacchae |

| 5.39 ‘lest you be found godfighters [θεομάχοι]’.[The Sanhedrin has arrested Peter and other Apostles. The Pharisee Gamaliel argues for their release, on the ground that time will tell whether their movement comes from man or God. If the former, its falsity will soon be exposed; if the latter, ‘you will not be able to undo them, lest you be found godfighters’, i.e. you will then be punished for impiousness.] | 45 ‘who fights against god in the matters regarding me’. [Dionysus in criticism of Pentheus, who rejects Dionysus’ cult];cf. also 325 ‘and I won’t fight against god persuaded by your words’ [Teiresias to Pentheus];540-4 ‘Pentheus … who fights against the gods’ [chorus];635-6 ‘for, being a man, he dared to come to a fight against a god’ [Dionysus on Pentheus];788 ‘suffering badly at your hands, nevertheless I say that you must not raise up arms against a god’ [disguised Dionysus warning Pentheus];1255-6 ‘but that man is able only to fight against god’ [Agave on Pentheus]. |

| 9.1 ‘Saul, still breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord’ | 620 ‘[Pentheus] breathing out his passion’ |

| 12.7 ‘and the chains fell off their hands’,12.10 ‘[the iron gate the one that bore toward the city] opened for them all by itself’, of Peter and his companions’ miraculous escape from prison.Cf. 5.19 ‘an angel of the Lord opened the prison doors’ (of the second imprisonment of Peter and the Apostles)and 16.26 ‘and immediately all the doors were opened and the bonds of all were undone’ (of the miraculous freeing of Paul and Silas and the other prisoners at Philippi) | 447-8 ‘all by themselves the chains were undone from their feet, and the bolts loosed the doors without mortal hand’, of the miraculous escape of the imprisoned Bacchants. |

| 17.18-21…-32 [Paul in Athens] ‘others said, “he seems to be an announcer of strange [ξενων] deities.” (For he was reporting the good news about Jesus and the Rising.) And they took hold of him and led him to the Areopagos, saying: “May we know what this new teaching is which is spoken by you? For you are introducing to our ears certain strange [ξενίζοντα] things. So we want to know what these things mean”. For all the Athenians and the strangers [ξένοι] that were staying there spent their time on nothing other than saying or hearing some rather new thing … But when they heard the rising of corpses, some mocked …’ | 216 ‘I hear of the new evils in this city’;219-20 ‘the new deity Dionysus’;247 ‘whoever the stranger is’ [of the disguised Dionysus];256 ‘introducing this new god to men’ [all spoken by Pentheus];272 ‘this “new” god, whom you mock’;

cf. 467; epithet ‘stranger’ repeatedly applied to disguised Dionysus. Cf. also Xenophon, Memorabilia 1.1.1 ‘Socrates acts unjustly, not believing in the gods that the city believes in but introducing other and new deities’; similarly Plato, Apology 24b-c. |

| 17.27-9 [Paul to the Athenians] “to seek the Lord… who is indeed not far from each one of us. For in him we live and move and are, as actually some of your poets have said: for we are his offspring.” | 506 [Dionysus disguised as the stranger to Pentheus] ‘you do not know what you are living,nor what you are doing, nor who you are.’ |

| 17.34 ‘certain men joined him and believed, among whom was Dionysios the Areopagite and a woman by name Heifer [Damaris] and others with them’ (of Paul’s converts in Athens) | 2 ‘Dionysos’ (name constantly recurs), 100 (Dionysos as bull), many other ‘bullish’ allusions |

| 26.14 ‘it is hard for you to kick against the pricks’[Jesus to Saul in the third telling of Paul’s conversion] | 794-5 ‘I would sacrifice to him rather than become angry and kick against the pricks, a mortal against a god’ [Dionysus in disguise advising Pentheus] |

These are, as Moles says, “objective” verbal parallels. They are clearly identifiable. (Those that I have colour coded yellow, green and purple are original to John Moles.) The question to be asked is how to explain them. Are they accidental? Or are they “real” in the sense that they “do things”?

On the first one Moles comments:

While the thought of [the first parallel] is perfectly Jewish, it is also a common Greek religious concept, it is a Leitmotiv of Bacchae, the Greek compound ‘fight against G/god’ (and cognates) is distinctive, it is found only here in the New Testament, and the item fulfils the same narrative and theological function in Acts and in Bacchae: that of the ‘wise warning’ disregarded by persecutors. (Gamaliel’s audience obeys here, but not later.) Interestingly, scholars debate the historicity of Gamaliel’s intervention (certainly, some of his arguments are anachronistic).

The second one (yellow) is only a slight verbal parallel but it would gain considerably more force if it could be shown that Paul was playing a Pentheus role as persecutor.

The third parallel, speaking of “falling off by itself”, is not of itself significant. What is significant, however, is that such descriptions are associated with Dionysiac epiphanies in the Classical literature.

The fourth (green) parallel is an interesting mix. Euripides wrote Bacchae in the time of Socrates and an age of considerable anxiety over the introduction of “new” cults into Athens. In the works of Plato and Xenophon we find that Socrates was soon afterwards accused of introducing “new” gods, not “strange” ones. Euripides has combined the fears of his own day with the traditional material that introduced a “strange” god into Greece in an earlier age. Similarly, Paul in Acts is portrayed as a Socrates figure (the parallels with Plato and Xenophon have been published elsewhere), but also appears to link the same figure to the Bacchae with its theme of mocking the new god.

The fifth parallel refers to the famous line in Acts that Paul attributes to “some of your poets” — addressing the Athenians. Commentators have noted the line “we are his offspring” comes from Aratus, and there is also an allusion to the Stoic philosopher Cleanthes. Moles, however, points out that neither of these men were Athenian, although the latter was Athenian at least by residence. Could Paul have been referring here, then, to the Athenian Euripides with the line, “in him we live and move and are”?

The contexts are similar. Paul is arguing that the Athenians are ignorant and do not realise the proximity of the one true god. Equally, Pentheus does not realise that Dionysus is ‘near’ . . . and the ‘stranger’ (Dionysus himself) upbraids Pentheus’ ignorance. ‘In him we live and move and are’ represents the polar opposite of Pentheus’ ignorance. This reconstruction attributes dense literary allusion, sliding phraseology and decidedly fancy footwork to Luke:* exactly as in [the preceding parallel]. The two items go together and are mutually reinforcing.

* Also of course to the dramatic Paul, who comprehensively outwits his stuck-up Epicurean and Stoic philosophical opponents and who is the real ‘poet’ here: Moles (2006).

In the sixth match we have the name Dionysios which means Dionysiac, and the name Damaris. Damaris is unusual/unique — the common form of the name is Damalis. Damalis has been changed to Damaris, which means Heifer. This could be an explicit allusion to Dionysus as the bull god — which he was Bacchae, taking on the form of a bull. Even if the two individuals were historical, the author has used some licence to make them the first-fruits of Paul in Achaia, since we know from 1 Corinthians 16:15 that they were not.

In the sixth match we have the name Dionysios which means Dionysiac, and the name Damaris. Damaris is unusual/unique — the common form of the name is Damalis. Damalis has been changed to Damaris, which means Heifer. This could be an explicit allusion to Dionysus as the bull god — which he was Bacchae, taking on the form of a bull. Even if the two individuals were historical, the author has used some licence to make them the first-fruits of Paul in Achaia, since we know from 1 Corinthians 16:15 that they were not.

The final parallel is well-known. As Moles stresses, it is Greek, not Jewish; it is not a common proverb but it is used in Greek tragedy and it is used in Bacchae — and Acts: “the persecuted and unrecognised god uses the proverb in direct exhortation of his chief persecutor.”

For John Moles, the above verbal parallels, especially the first, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh, “prove use of Bacchae and of more general Dionysiac material.”

Other Dionysiac material in Acts

D. The first prison escape

Acts 5:19-25 is the first instance in Acts of a miraculous prison escape. The scene follows the initial arrest and interrogation of Peter and John (4:1ff) and culminates in the warning by Gamaliel that likewise was shown (above) to be linked to the Bacchae. It follows the same narrative pattern as 12:1-10 and 16:26-30 (also above). The scene in Acts where the spotlight is put on the guards consternation at guarding the prisoners only to find them outside the prison corresponds to Bacchae 644-6:

Pentheus: I have suffered terrible things; the stranger, who was recently constrained in bonds, has escaped me. Ah! Here is the man. What is this? How do you appear in front of my house, having come out?

E. Pentecost

Another possibility Moles finds discussed in the literature is the Pentecost scene where the apostles are mocked (Acts 2:13) as being “filled with sweet wine” for speaking in various tongues. Sweet wine implies new wine (“and the phrase is a proverbial allusion to widespread drunkenness when the year’s new wine first becomes drinkable” — Wallace-Williams, 1993:36) and Peter denies the accusation: “These men are not drunk, as you take it, or it is the third hour of the day”.

Now, drunkenness is a feature of Dionysiac wine festivals such as the Anthesteria,

Dionysiacs got drunk at night,

they were divinely possessed,

forms of glossolalia featured in pagan cult,

Dionysus cult was the most international of pagan cults,

Pentheus accuses the Bacchanals of drunkenness and mocks the new god,

but the charge of drunkenness is denied by the Messenger,

and the Acts narrative opposes the mockery with an idealised description of the Christian life at 2.42 and 44-46, which includes ‘the breaking of bread’.

While scholars dispute whether in Acts ‘the breaking of bread’ refers to, or includes, the Eucharist,35 given that Acts 2.42, 27.35, etc. ~ Luke 22.19 ~ 24.30, the allusion must at least be included, so that, although Acts does not specify wine-drinking at such meals,36 a broad contrast remains between what is misapprehended as Dionysiac excess (2.13) and Christian table-fellowship. (p. 75, my formatting)

Note, also, that the Holy Spirit is pictured as a liquid. The apostles are “filled” with it (2:4); it is poured out (2:17-18, 33).

The function of the incorrect accusation of 2.13, therefore, is to imply a contrast between the ‘bad’ Dionysus of pagan religion and the ‘good’ Jesus who is the true wine.

And if we see the Apostles as “drinking the equivalent of the true, new wine”, then Pentecost will be looking back to three passages in the preceding and companion book to Acts:

- Luke 19-20 and the Lord’s Supper. There the cup of wine was “poured out” and was the “new covenant of [Jesus’] blood”.

- Luke 7:32 where Jesus defends his notoriety as a wine-drinker in contrast to the ascetic life of John the Baptist. When Jesus imagines the crowd complaining because John did not dance when they played the pipes for him, he is apparently (Freyne, 2000, 2004) alluding to the devotees of Pan and Dionysus.

- Luke 5:33-38. In another contrast between John and Jesus, Jesus speaks the parable of no-one putting new wine into old wineskins, lest the new wine breaks the old wineskins and is poured out. New wine must be put in new wineskins.

So the Pentecost narrative belongs within a complicated sequence – which extends back through Acts 1 and into the Gospel – concerned with the relationship, within first-century Judaism, Jesus’ ministry, and early Christianity, between the old and the new, between Jesus and the Baptist, and between Jesus and wine, and within that sequence Dionysus plays an important role both of comparison and of contrast.

The Consequences

So what does all of this mean? What was the point of making Dionysiac allusions in Acts, and even in the Gospels? That is the real question and the one that John Moles addresses in the second half of his article. . . . . .

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Moles is not a New Testament scholar, and this is clearly a case of parallelomania if we ever saw one. Therefore, we’re entitled to ignore everything he’s written here. Signed, the Society of Biblical Literature.

Already departing from Sandmel’s advice not even 2 1/2 weeks later? I particularly got a kick out of the section “Verbal parallels between Acts and Bacchae” and “Broad thematic parallels between Acts and Bacchae,” which immediately reminded me of that which you yourself quoted:

“the excessive piling up of . . . passages. Nowhere else in scholarly literature is quantity so confused for quality . . . . The mere abundance of so-called parallels is its own distortion . . .”

You always bat down Harper trolls with, essentially, ‘if we can find a source of influence within the Old Testament and Jewish culture, then there’s no need to appeal to things outside of that.’ There’s certainly plenty of that already to account for the make-up of Acts. And even that is, of course, only if you even think that necessary to account for it.

Alas, once a parallelomaniac, always a parallelomaniac.

Once a troll, always a troll. Spoken like a closed-minded theologian who has evidently never read Sandmel in full and only quote-mines his article. The exercise here that a classics professor is able to engage in with positive feedback from a host of other scholarly names mentioned in this post and publish in a venerable peer-review classics journal is the very sort of exercise in literary analysis that Sandmel in fact endorsed. But of course in the eyes of some ignoramuses any literary analysis is a laughing stock by definition. I suppose you’d laugh at the very idea that Virgil used Homer or that Hellenism had any cultural impact upon any literate Jews.

I have long thought Acts 26:14 was Luke using a Greek cliche from the Bacchae just as we use unwittingly use cliches from Shakespeare. I am amused that we have Luke quoting Paul quoting Jesus coming down from heaven and translating a Greek cliche into Aramaic to quote Euripides quoting Dionysus. Now it seems it wasn’t an accident.