We have covered the subject of the apostle Paul’s silence on Jesus’ life many times on Vridar. But for quite a while now, I’ve been thinking we keep asking the same, misdirected questions. NT scholars have kept us focused on the narrow confines of the debate they want to have. But there are other questions that we need to ask.

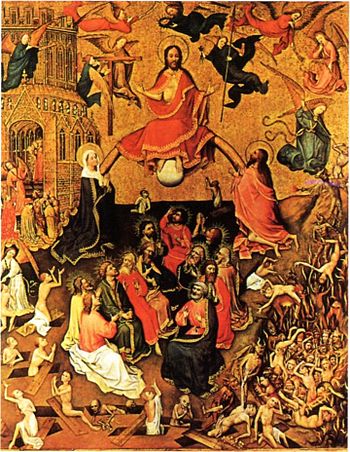

Pretty apocalyptic prophets, all in a row

For example, Bart Ehrman, defending his claim that Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet, has habitually argued that we can draw a sort of “line of succession” from John the Baptist, through Jesus, to Paul. In Did Jesus Exist? he explains it all in an apocalyptic nutshell:

At the beginning of Jesus’s ministry he associated with an apocalyptic prophet, John; in the aftermath of his ministry there sprang up apocalyptic communities. What connects this beginning and this end? Or put otherwise, what is the link between John the Baptist and Paul? It is the historical Jesus. Jesus’s public ministry occurs between the beginning and the end. Now if the beginning is apocalyptic and the end is apocalyptic, what about the middle? It almost certainly had to be apocalyptic as well. To explain this beginning and this end, we have to think that Jesus himself was an apocalypticist. (Ehrman, 2012, p. 304, emphasis mine)

Dr. Ehrman sees the evidence at the ends as “keys to the middle.” For him, it’s a decisive argument.

The only plausible explanation for the connection between an apocalyptic beginning and an apocalyptic end is an apocalyptic middle. Jesus, during his public ministry, must have proclaimed an apocalyptic message.

I think this is a powerful argument for Jesus being an apocalypticist. It is especially persuasive in combination with the fact, which we have already seen, that apocalyptic teachings of Jesus are found throughout our earliest sources, multiply attested by independent witnesses. (Ehrman, 2012, p. 304, emphasis mine)

You’ve probably heard Ehrman make this argument elsewhere. He’s nothing if not a conscientious recycler. Here, he follows up by summarizing Jesus’ supposed apocalyptic proclamation. Jesus heralds the coming kingdom of God; he refers to himself as the Son of Man; he warns of the imminent day of judgment. And how should people prepare for the wrath that is to come?

We saw in Jesus’s earliest recorded words that his followers were to “repent” in light of the coming kingdom. This meant that, in particular, they were to change their ways and begin doing what God wanted them to do. As a good Jewish teacher, Jesus was completely unambiguous about how one knows what God wants people to do. It is spelled out in the Torah. (Ehrman, 2012, p. 309)

Unasked questions

However, Ehrman’s argument works only if we continue to read the texts with appropriate tunnel vision and maintain discipline by not asking uncomfortable questions. Ehrman wants us to ask, “Was Paul an apocalypticist?” To which we must answer, “Yes,” and be done with it.

But I have more questions. Continue reading “The Memory Mavens, Part 6: How Did Paul Remember Jesus?”