William Wrede’s The Messianic Secret

Part 6: “The Self-Concealment of the Messiah” — Demons (cont’d)

This unit continues Part 1, Section 2 (p. 24) of Wrede’s The Messianic Secret.

Revealing and Concealing

As we have seen, Wrede agreed with the critics of his day that Mark’s Jesus seems to be intent on keeping it a secret that he’s the messiah. Yet, right next to the commands to silence, we find testimony to the fact that Jesus’ fame spread far and wide.

And he charged them that they should tell no man: but the more he charged them, so much the more zealously they proclaimed it; (Mark 7:36, KJV)

Similarly, the disciples seem to alternate from ignorance to knowledge and back again. Wrede’s concern is to discover where this motif comes from. Is it purely a literary convention, or is it historical? If it is a literary motif, was it present in his sources or is it a Markan invention?

By examining the various manifestations of the Messianic Secret, perhaps we can discover its roots and significance. Ultimately, thought Wrede, such knowledge may help us reveal authentic traditions of the historical Jesus.

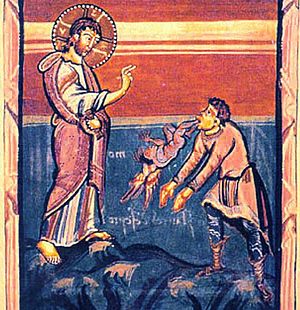

Exorcism and the Messianic Secret

The exorcism stories in Mark provide two distinct aspects of the Messianic Secret. First, obviously, are Jesus’ commandments of silence. A more subtle, secondary aspect is the spiritual rapport between Jesus (now endowed with the pneuma) and the unclean spirits. In other words, the fact that the demons know exactly who Jesus is simply by being nearby, or as Wrede puts it:

A direct rapport exists between him and them; it is not tied to any earthly means of communication. Spirit comprehends spirit, and only spirit can do so. For this reason, the idea that Jesus’ messiahship was a secret is not to be found merely in the command to be silent but is already independently present in the circumstance that the demons know about him. Their knowledge is secret knowledge. (p. 25 — emphasis mine)

Demons detect the proximity of Jesus and immediately know who he is and what his presence on the earth means — namely, that they’re in imminent danger. Further, while they can’t help being terrified by the presence of Jesus, they are “magically drawn to him.” (p. 26)

Continue reading “Reading Wrede Again for the First Time (6)”