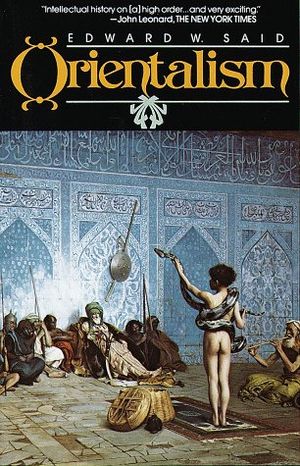

Trying to think through the question of modern antisemitism before writing my previous post I pulled off a shelf my old copy of Edward Said’s Orientalism. I was surprised to see how much I had forgotten, and to discover where some of my views on modern Islamophobia and racist attitudes towards Middle Easterners may have been born. Some extracts:

Trying to think through the question of modern antisemitism before writing my previous post I pulled off a shelf my old copy of Edward Said’s Orientalism. I was surprised to see how much I had forgotten, and to discover where some of my views on modern Islamophobia and racist attitudes towards Middle Easterners may have been born. Some extracts:

For whereas it is no longer possible to write learned (or even popular) disquisitions on either “the Negro mind” or “the Jewish personality,” it is perfectly possible to engage in such research as “the Islamic mind,” or “the Arab character” . . . (262)

Further on….

Yet after the 1973 war the Arab appeared everywhere as something more menacing. Cartoons depicting an Arab sheik standing behind a gasoline pump turned up consistently. These Arabs, however, were clearly “Semitic”: their sharply hooked noses, the evil mustachioed leer on their faces, were obvious reminders (to a largely non-Semitic population) that “Semites” were at the bottom of all “our” troubles, which in this case was principally a gasoline shortage. The transference of a popular anti-Semitic animus from a Jewish to an Arab target was made smoothly, since the figure was essentially the same.

Thus if the Arab occupies space enough for attention, it is as a negative value. He is seen as the disrupter of Israel’s and the West’s existence, or in another view of the same thing, as a surmountable obstacle to Israel’s creation in 1948. Insofar as this Arab has any history, it is part of the history given him (or taken from him: the difference is slight) by the Orientalist tradition, and later, the Zionist tradition. Palestine was seen—by Lamartine and the early Zionists —as an empty desert waiting to burst into bloom; such inhabitants as it had were supposed to be inconsequential nomads possessing no real claim on the land and therefore no cultural or national reality. Thus the Arab is conceived of now as a shadow that dogs the Jew. In that shadow—because Arabs and Jews are Oriental Semites—can be placed whatever traditional, latent mistrust a Westerner feels towards the Oriental. For the Jew of pre-Nazi Europe has bifurcated: what we have now is a Jewish hero, constructed out of a reconstructed cult of the adventurer-pioneer-Orientalist (Burton, Lane, Renan), and his creeping, mysteriously fearsome shadow, the Arab Oriental. (285-86)

The Arab mind . . .

There are good Arabs (the ones who do as they are told) and bad Arabs (who do not, and are therefore terrorists). Most of all there are all those Arabs who, once defeated, can be expected to sit obediently behind an infallibly fortified line, manned by the smallest possible number of men, on the theory that Arabs have had to accept the myth of Israeli superiority and will never dare attack. One need only glance through the pages of General Yehoshafat Harkabi’s Arab Attitudes to Israel to see how — as Robert Alter put it in admiring language in Commentary — the Arab mind, depraved, anti-Semitic to the core, violent, unbalanced, could produce only rhetoric and little more. (307)

The fact about Islam . . .

Lewis’s polemical, not scholarly, purpose is to show, here and elsewhere, that Islam is an anti-Semitic ideology, not merely a religion. He has a little logical difficulty in trying to assert that Islam is a fearful mass phenomenon and at the same time “not genuinely popular,” but this problem does not detain him long. As the second version of his tendentious anecdote shows, he goes on to proclaim that Islam is an irrational herd or mass phenomenon, ruling Muslims by passions, instincts, and unreflecting hatreds. The whole point of his exposition is to frighten his audience, to make it never yield an inch to Islam. According to Lewis, Islam does not develop, and neither do Muslims; they merely are, and they are to be watched, on account of that pure essence of theirs (according to Lewis), which happens to include a long-standing hatred of Christians and Jews. Lewis everywhere restrains himself from making such inflammatory statements flat out; he always takes care to say that of course the Muslims are not anti-Semitic the way the Nazis were, but their religion can too easily accommodate itself to anti-Semitism and has done so. Similarly with regard to Islam and racism, slavery, and other more or less “Western” evils. The core of Lewis’s ideology about Islam is that it never changes, and his whole mission is now to inform conservative segments of the Jewish reading public, and anyone else who cares to listen, that any political, historical, and scholarly account of Muslims must begin and end with the fact that Muslims are Muslims. (317-18)

Said, Edward W. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.